The Wessex Project: Thomas Hardy, Architect: Part I

This is the first of three extracts, each a series of vignette studies, that we will publish over the next few weeks; they are all taken from Kester Rattenbury’s fascinating full-length study: The Wessex Project: Thomas Hardy, Architect, which approaches the great author from the perspective of his first career as a young architect in London and Dorset.

As he established himself as a novelist and poet, Thomas Hardy gave up architecture as a profession, but that early experience both directly and indirectly remained an inescapable presence throughout his written work and in the development of his vision of Wessex – and also at Max Gate, the house that he later built for himself and his wife.

– Niall Hobhouse

Architectural Library

From the great purge of papers, which Florence Hardy continued after his death, a range of direct architectural work had been saved. Some drawings are exquisite, some are scrappy and peculiar. Some are detailed roughs, some are clearly for presentation, and there are several for laying out drains. There is the architectural notebook, that carefully assembled mini-portfolio of sketches, copies, notes and designs, which he continued into his eighties – and a big quarter-scale, carefully coloured drawing of the lavatory at Max Gate: the biggest design drawing of all. Some were jobs Thomas Hardy designed in his own right, some were for other architects. Some were built, others not, and there is no immediate way of seeing which is which. The shape of this inchoate, far-from-perfect mass of saved architectural drawings is interesting. Hardy is showing he could draw, competently and with skill, in the manner required by his profession – but elevations of new buildings are the most mechanical parts of his work. His sections are much better; his surveys of existing buildings are lovely. His rough working drawings – plans and sections – are often more engaging than the ‘finished’ ones: you can see Hardy working everything out, in intense detail.

Some finished drawings are extremely revealing: the lovely drawings of his Piddletrenthide school extension (perhaps coloured to show to the children) or the complete church design, which Claudius Beatty uncovered (and which looks like a competition entry). It is an accomplished, sparse Arts & Crafts style, with unusual random modern stained-glass windows, but most remarkable is that immersive, wonderful section drawing. To see it as close, as Hardy would have drawn it, is like actually being in the building: an astonishing level of skill (if too time-consuming to use often). The coloured pew-end series in the manner of Owen Jones’s The Grammar of Ornament (from which Hardy copied many of his drawings [1]) suggests a detailed catalogue from which to work. The regal lavatory drawings are expressive and accurate: grand, personal indoor plumbing as the ‘throne’ of Max Gate. And the drawings of the Greenhill houses in Weymouth, a richly detailed conventional terrace in Victorian Gothic coloured brick look like a textbook exercise in formal style.

But beware of thinking that accomplished styles or exquisite, finished drawings define Hardy’s architecture: the opposite is often true. Hardy moved away from elevations, first to ‘inside out’ Arts & Crafts type thinking, and on to a kind of accretive patching in which his later designs were not drawn in complete elevation at all. He was not leaving us a finished vision in those drawings, but a sample of the range of ways in which he was visualising and constructing the world.

The Notebook, though stiff with decorative details, is intercut with notes on housemaids’ sinks or details of a ‘French’ drain, acoustic floor-packing (as in Ethelberta), or everyday, lightweight, functional roof construction details, both drawn and written. Later, there are detailed, rougher measured studies of projects he was actually building. He is showing himself to be working, thinking, designing as a hands-on, capable architect: alongside, and through, everything else.

I am also considering the remarkable things he is not drawing. Signs of sketching ideas for buildings are scarce or conventional. He is often copying, tracing or scaling up. He does not seem able to draw in isometric (however lovingly he describes that aristocratic architectural drawing). He does not seem to draw in perspective at all: there is no sign of the vanishing points or ‘setting out’ lines used to construct them, although several drawings use grids to help with the simple ‘scaling-up’ of flat images.

Many of the drawings are miniscule; some in strange focus. I am constantly wondering about his eyesight and his lifelong use of lenses. Remarkably, he seems to be tracing photographs, reproducing their framing, focus and photographic distortion. There are small, detailed, complex images, stopping in a neat rectangular frame, in the middle of a large piece of paper (Stinsford House); there are ones where the distance is more in focus than the foreground (Melbury Osmund); and a neat, finished drawing of the pew-ends of St Juliot before restoration, which can be neatly fitted over the photograph itself.

There are few original photographs left in the archive (the one of St Juliot was saved by the vicar), but this is not a coincidence. Camera lenses construct the view in one way; perspectives, drawings and human perception in others. They would not naturally produce the same views. Other drawing devices might, however: notably the nineteenth century camera lucida, described and illustrated in Martin Kemp’s The Science of Art. [2] The Fox Talbot and Basil Hall drawings which Kemp shows in his book are very like Hardy’s otherwise peculiar, scrappy drawings, dated 1861 and 1862, when he first moved to London and started visiting the Great Exhibition. This device used a little mirror lens, focusing a picture onto a flat desk, working a little like an overhead projector. A further peculiarity is that the user is looking through the lens while drawing, rather than looking directly at the paper, making it much harder to do. I am struck by the way that groups of trees, or even blocks of landscape are drawn as a single, solid outline block, sometimes in frenetic detail, rather than drawn tree by tree, or hill by hill, as untrained humans tend to do. Some of the finished-looking views from windows also suggest some similar process with detailed outline and infill; others perhaps are taken from photographs. From a visual point alone, I would suggest that Hardy was, from his arrival in London, exploring image projection as one of his many working tools for capturing and developing his view of the world.

He uses old techniques as well as new. All the tracings, overlays, arch-mould stencils, copies and experiments in the Notebook, the lenses, photographs, home-made carbon paper (where lead would be rubbed on the back of paper and the original re-drawn, so that the image was ‘transferred’ onto a fresh page below), are in this realm. From his obsessive drawings of tombstones and memorials – a move backward into the ‘traits’ or tracing used by mediaeval craftsmen (he does masses of full-size gravestone drawings) – to the photographic cut-out of his family’s exquisite traditional music book in Hermann Lea’s book and the stage set work late in life, Hardy is working in the familiar realm of architecture’s continual reinvention of itself through drawing and representation, through precedent and invention.

There is plenty of internal evidence within the novels suggesting an experimental fascination and familiarity with lenses, photography, and phantasmogria. No one reading Ethelberta or A Laodicean should be surprised by this. But it takes some familiarity with ‘normal’ architectural drawing techniques to recognise peculiarities in these drawings – and hence in this form of his drawings we see a new way of understanding how Hardy saw and represented the world. [3]

Hardy’s drawings are a key part of his intense, broader interest in perception, which extends to the way an architect imagines the invisible qualities of architecture – which can be designed, built, touched, experienced – but not exactly drawn or photographed. Acoustic space; age value; social experience; the craftsman’s understanding of worked stone. (Even those Dorset County Chronicle local news articles mention the experience of the congregation.)

All forms of representation are limited, selective, partial. Hardy’s architectural vision is certainly not contained in any one particular type of drawing, and the whole range of representation and drawing was, I would argue, by now part of the processes he was using to generate his work. Even if, at this point, it was largely emerging in written and fictional form.

The White Horse Inn in Maiden Newton

The White Horse Inn, in Maiden Newton, another failed campaign of the late 1890s, has Hardy’s fingerprints (perhaps literally) all over it. It was Hardy’s old boss George Crickmay who quietly notified The Society for Protection of Ancient Buildings that one of their clients, Weymouth brewers Devenish, were planning to knock down the fine Elizabethan building. Crickmay were architects for the project, so informing against their paying client was what Beatty calls ‘public spirited’ – in the extreme. I’m wondering what excellent impulse – or whose – prompted this extraordinarily disinterested action.

Thomas and Emma Hardy seem to have cycled straight over. Perhaps Hardy left Emma painting her watercolour outside; (SPAB says ‘even from a commercial point of view the front was most valuable’ [1]), as a demonstration, while Hardy carefully examined the inn and talked to the irritated landlord. Hardy is carefully sympathetic. He scrupulously charts the problems to SPAB – ‘roof, floors &c., are so bad that something must be done soon to keep the building together’, the terrible condition of the upper rooms; ‘the insurance of thatch is enormous’. He also gave the landlady a copy of his Wessex Tales, which mentions it as a fine Elizabethan building.

Hardy, Crickmay and SPAB all seem to propose workable compromises, all possibly coming from Hardy himself. Hardy (and SPAB, presumably quoting him) think the solution would be to keep the rooms at the front; sacrifice partition walls which are not original ‘for instance, a fine, four-centred stone fireplace, that formerly warmed a large room, is now shut up in a small one’. He tries and fails to talk the landlord out of his dogged requirement for high-ceilinged rooms, but got him to say exactly how high he would regard as acceptable (1′ 3″ to the lower rooms; 2′ 6″ to the front wall). These measurements appear on the alternative scheme, purportedly by Crickmay, for a better rebuilding of the whole thing (a device much used by our own latterday conservation campaigners [2]). Crickmay would not have been paid for that work and the drawing style looks, at least possibly, familiar: look at the little section, and the oddly hybrid handwriting. The drawing, in fact, follows SPAB’s/Hardy’s brief: it is quite possibly his.

But the brewers weren’t interested. The whole thing was pulled down, and replaced. [3] There is a photographic account – a blurred action photograph of the five feet of thick, dusty thatch being stripped and thrown down, and a carefully saved shot of the distinctly poor modern replacement, now flats. SPAB’s report regretfully said: ‘It might be thought that even from a commercial point of view, the owners would have decided to retain the building, as there are many who spend their holidays in travelling about to see buildings such as this […]’. [4]

Beatty says this led to a specific course of action in Hardy’s fiction. The building had first appeared (anonymously) in the 1874 story Destiny and a Blue Cloak, then in 1884 as The Pack Horse in Interlopers at the Knap. By 1896 it has the high Wessex status of its own name. In 1912 revisions it is ‘the fine old Elizabethan Inn at Chalk-Newton’; a footnote adds, ‘It is now pulled down, and its site is occupied by a modern one in red brick’ – ‘as if he wanted to make quite certain that it should never be forgotten’, says Beatty. [5] This sounds just like what Hardy did with The Three Mariners in The Mayor of Casterbridge. He was disseminating a warm, human, loving polemic for everyday, unfashionable buildings which most middle-class people would have avoided. He was doing this in fact and fiction: deliberately informing, impassioning and charming his vast readership; staking out a new, informed vision of the built past – and silently shifting the context for those working to save it.

Max Gate

Hardy specifically said he did not want to ‘ruin himself with architecture by building a great house as other literary men have done’. [1] Architecturally, that implicates Pugin, who built his own first house, St Marie’s Grange (another first project, done when already famous), then redesigned it, and later sold it, losing a great deal of money. [2] He then built another house in Margate: plainer – except for having its own truncated church and gallery attached. Hardy might well have seen St Marie’s Grange (1835) outside Salisbury. It was also criticised for its exteriors at the time; [3] the original published ‘sketch’ was by Benjamin Ferrey, already mentioned, and of course, it is in Wessex. St Marie’s second phase actually looks rather like Max Gate: the tower, the half-hipped roof, the varied and irregular windows.

Another, more famous model might be the Red House (1858–1860), by Philip Webb for (and with) William Morris, which also has an open hall with a neo-Gothic, backlit stair. Now seen as one of the greatest works of the Arts & Crafts movement, it too was criticised (at the time) for its irregular exterior; it too cost a lot of money; and despite its fame now, Morris also later moved out. [4]

Max Gate was simpler. The original plan (the early 1880s house, before the extensions) has a central door, a parlour on each side, and a kitchen at the back – with a traditional central hall, just like a miniature country house. Three bedrooms in a row above it (bedroom, dressing room, study) – three attics above that. (I am consciously paraphrasing E. M. Forster’s Howards End, one of the most loving descriptions of a house in English Literature. Forster too would become a friend and regular visitor.)

In Hardy’s Architectural Notebook, there are several pages showing comparative plans of houses Hardy knew or had worked on (‘almost’). Beatty suggests these may have been places he was going to describe; but they are drawn at the same size, all together, which suggests comparative design thinking – houses he was considering as models for Max Gate. (Imagining even fictional houses would certainly have helped stock his natural architect’s image-bank of spatial ideas.) All look fairly normative (they are not famous); he must have been thinking how their layout worked. But on the next page are the ‘Kingston’ drawings which Beatty says he used for Knapwater in Desperate Remedies, with its grand central top-lit hall and two staircases. And the major architectural element in Max Gate is its hall and stairs. That is an absolutely key feature of the Arts & Crafts’ modern reclamation of the English typologies of farmhouse and castle.

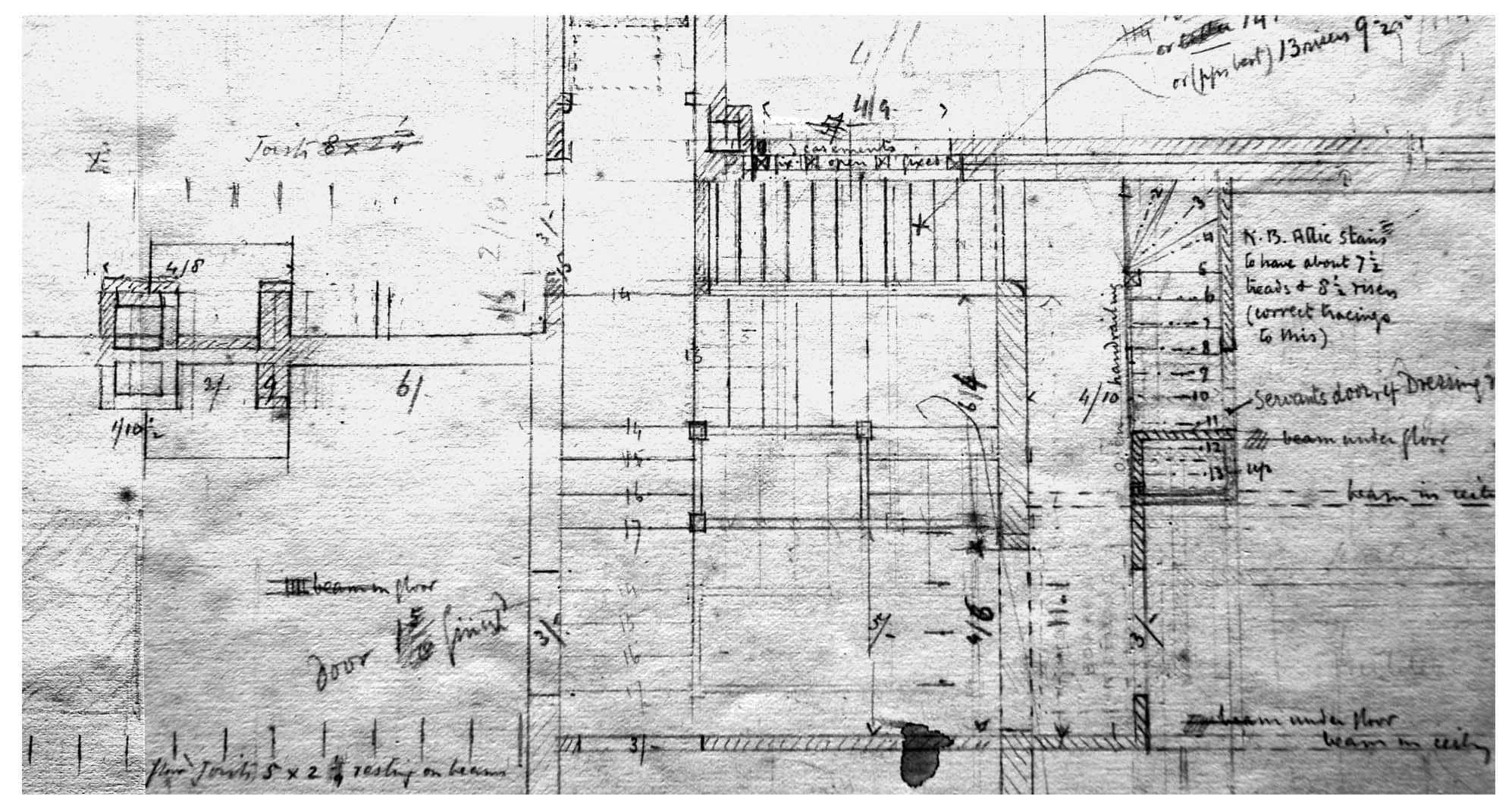

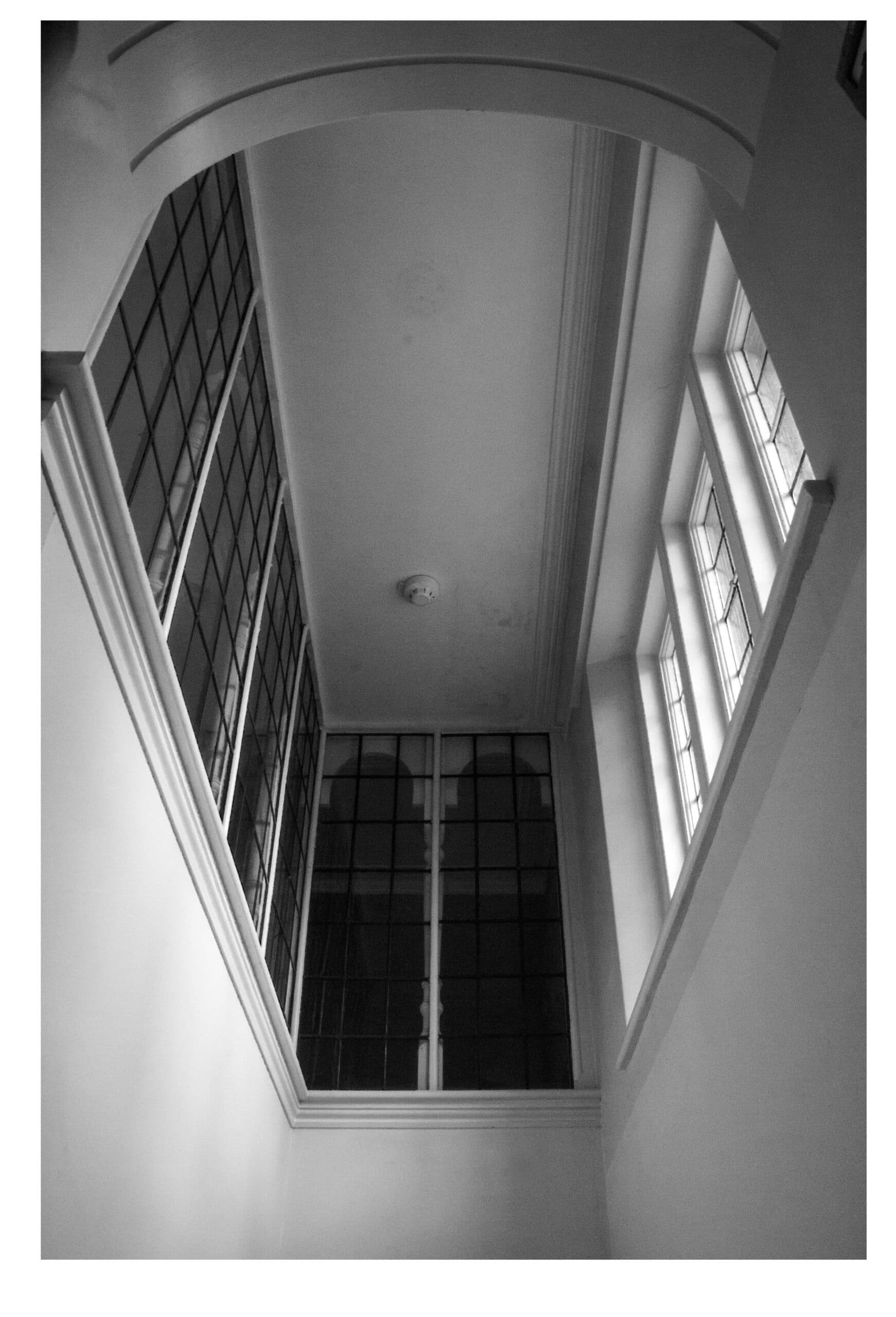

For a house of its size, Max Gate’s hall is very elaborate. It is as big as the two main front rooms, with an open, top-lit, three-flight staircase rising to the first floor. But hidden behind the stair – in the depth of the two-layer window – is the servant stair, enclosed, narrower, leading in two steep flights into the pretty attics – without touching the first floor at all. So the hidden ‘servant’ stair wraps round the main ‘served’ stair, top-lit by its high-level window, forming an elaborate double ‘clerestory’ to the hall itself.

Staircases are complicated to design, and Hardy has worked on this. It is elaborate, complicated, and begging to be drawn in exploded axonometric (more 1970–1980s design tools; a sort of measured diagram) to show how its compact, interlocking circulation works. This is the heart of Max Gate, architecturally: a kind of comic staging of served and servant workings of the house – intimate, interlocking, separate – which is very good indeed. It is the architectural parti: the big idea. And about four-fifths of it work brilliantly. But it is too tight and crowded. Emma Hardy, reasonably, complained of falling over the servants. Hardy, at this stage, prioritised technical detail over sheer space: he would not make his main rooms big enough until the extensions.

But problematic or not, the ‘served–servant’ relationship – the Desperate Remedies and Hand of Ethelberta idea – was the heart of this project, and all the richest bits of Max Gate’s architecture come straight from it. It shows us the problems the Hardys were facing in their own marriage in architectural form, and the way Hardy tried to solve (and sometimes contributed to) them through architecture. The problem was all about servants.

These vignettes are extracted, with permission, from The Wessex Project: Thomas Hardy, Architect by Kester Rattenbury, published by Lund Humphries, available here. The second and third series of vignettes will be published over the next few weeks.

Additional thanks to Toucan Press for the use of Hermann Lea material.

Notes

Architectural Library

- Claudius Beatty, Thomas Hardy and the Restoration of Rampisham Church (Privately printed, 1991), Introduction.

- Martin Kemp, The Science of Art: Optical Themes in Western Art from Brunelleschi to Seurat (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1991).

- I am indebted to Richard Difford for introducing me to Kemp’s book.

The White Horse Inn in Maiden Newton

- Claudius Beatty, Thomas Hardy, Conservation Architect (Dorset: Dorset Natural History & Archaeological Society, 1995), p.23.

- E.g. SAVE’s alternative developments for Mansion House or the Royal Opera House.

- Jo Draper, Dorset: The Complete Guide (Dovecot: The Dovecote Press, 2011); SPAB 1898; Claudius Beatty, Thomas Hardy, Conservation Architect, p.25.

- Claudius Beatty, Thomas Hardy, Conservation Architect, p.31.

- Ibid., pp.25-26.

Max Gate

- John Piper (1945)

- National Trust, accessed 4 October 2017.

- Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982; 1985), p.263.

- Ibid., p.260.