The Work of Ernest and Esther Born: World’s Fair

Ernest and Esther Born trained as architects at Berkeley in the early 1920s and worked with great distinction in all aspects of architecture and the allied arts, from graphics and illustration to display design and architectural photography. This project marks one of their first endeavours on returning to San Francisco in 1936, after ten years in Europe, New York and Mexico (where Esther’s 1935 photographs pioneered observations of the new architecture).

Planning for San Francisco’s 1939 World’s Fair had been launched in 1933 to celebrate the opening of the Bay Bridge (1936) and the Golden Gate (1937). It was well advanced by the time Ernest, after a summer in Mexico with Esther, settled there early in the fall of 1936. The fair was conceived as a ‘Pageant of the Pacific’. It was designed to boost the profile of the city as a gateway between the Americas and the burgeoning populations and markets of east Asia, promote the products of Northern California, and provide the groundwork – on a manmade island in the bay – for a new era in air travel, with the site scheduled for conversion into the city’s municipal airport and the base of operations for Pan Am’s celebrated flying boat service. The architectural team charged with the main exhibit buildings settled on a number of key premises. Buildings along the southeastern perimeter were to be designed for conversion to permanent airport facilities while the main exhibit halls and courts would be temporary structures that would reflect in modern form a fusion of the built traditions of the Maya with those of Angkor Wat and other ancients sites across the ocean.

This was a complicated and ambitious stylistic agenda intended to establish ‘a new mode’ for California architecture that its proponents christened ‘Pacifica’. The result, appearing very early in the process, was a vast enfilade of highly theatrical, monumental abstractions of everything from towering pagodas to East Asian pyramids crowned with elephants and howdahs, all re-thought in terms of the massive set-back monuments of ancient Mexico. Critics immediately dubbed it ‘Never-never land’. Only on the eastern perimeter in a cluster of government pavilions (whose designs emerged later), in William Wurster’s Yerba Buena Club for women, and among one or two of the national and corporate pavilions, were any gestures attempted toward the sort of futurist modernity that would generate so much excitement at the 1939 New York Fair and to which Ernest would surely have been more sympathetic.

All the principal exhibits were to be housed in windowless enclosed spaces and displayed by electric light, tempting architects to over-dress the dense structures that would house them. A standard colour palette prescribed nineteen hues associated with skies, natural environments or decorative traditions on both sides of the Pacific, from ‘pagoda yellow’, ‘Southern Cross blue’ and ‘Ming jade green’ on one side to ‘Death Valley mauve,’ ‘Pebble Beach coral’ and ‘Old Mission fawn’ on the other. To make more theatre of them, the great parades of stepped back stucco blocks were to be designed for night, so that colour-filtered searchlights, floodlights, and fluorescent illumination could play upon surfaces –some mottled with mica to enhance the effect – and highlight the perspectival drama. It was this technicolour walled city of night, whether close at hand or seen from the cities around the bay, that captured the imagination. Night views graced the cover of the official guide. Souvenir publishers devoted their postcard series and ‘viewbooks’ to illumination. By the first year’s closing in October 1939, the colours of the lighted island had become so firmly identified with the landscape of the Bay that the lighting designer’s decision to intensify the palette for a second season in 1940 provoked an outcry. Deploying many of the recent advances in light and colour technology from military, aviation, advertising and cinematic sources, the Fair’s experiments with light, within the pavilions as well as without, would be its main claim to modernity.

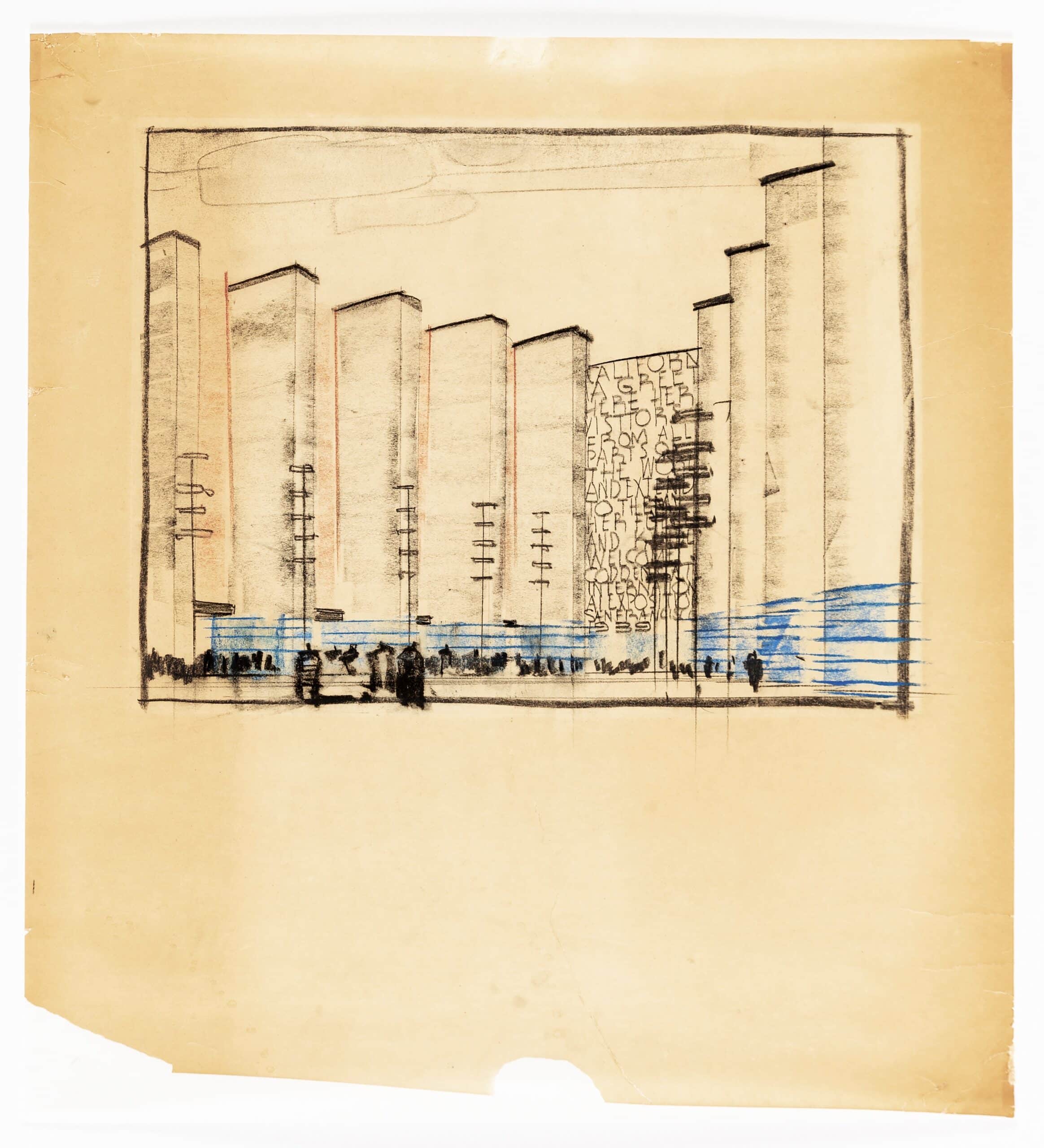

While Ernest came late to the Fair, his role was a large one. Early in 1937, he seems to have been charged with the critical task of rendering the pavilions for publicity and posters as they would be seen by night, producing a light show akin to the cities imagined on the silver screen. At the same time he proposed a scheme for the wind barriers that were to be installed at the two main entry points to shield the east-west promenades and their great entry courts from the breezes of the bay. As a published view of the ‘Model of the Main Entry’ shows, these ‘baffles’ consisted of two sets of upright stucco dominoes overlapping and stepping back behind the two main portals. Seventy feet high, the baffles filtered visitors through to the right and left as they entered the grounds. Ernest’s pastel sketch for an entry to the Golden Gate Fair proposed decorating the wider rear wall with a welcome panel, adding blue bands of light to the bases of the narrow baffles and coral strip lights behind them, and placing black caps on their tops and dark awnings over the openings between them. None of these ideas for detail, the inscription, or the rigorously geometric light pylons appeared in the final schemes, which were credited to Ernest Weihe, the designer of the western facade. But it is clear that Born’s drawing was developing ideas for the baffles and that the concept – geometric blinds in simple counterpoint to the fantastic elements around them – owes much to him.

A year later, in the spring of 1938, Ernest, now licensed in California, developed the general plan for an ensemble of three of the ‘county pavilions’. This was a late insertion into the scheme of the fair, through a state grant to profile the character and history of the state’s regions. Working under Henry T. Howard, architect for the Fair’s California Commission, Ernest himself designed two of three pavilions on a bayside plot and was responsible, though not credited, for the orchestration of the nearly two-acre precinct on which they sat. He was then charged with a mural celebrating California’s industries for the city pavilion. Finally, he designed a coloured plan of the Fair as a mural near the entry to the grounds and four major exhibits – for the California wine industry, for the Brazilian pavilion, for San Francisco’s public utilities, and for Del Monte Foods. Esther, in turn, was one of a number of photographers engaged to record the entire exterior of the site as it neared completion. Ernest complained of the politics inhibiting his county precinct, the difficulties of fitting coherent displays into rooms with awkward configurations, and the gradual sentimentalising of his ruggedly industrial California mural. But his county pavilions were among the very few elements to earn the regard of critics, and his path-finding artwork for the mural-plan was extravagantly published in full-colour foldouts by the national design monthlies.

Above all, the fair was a proving ground for many talents that blossomed in his years ahead. It brought Ernest’s long experiments with the lighting, cabinetry and colours of display to maturity. It provided his first independent opportunity to design public buildings and configure open space, introducing ideas – like circular paving, pylons, posts and light screens – to which he would return in his city works and transit stations. It brought him to questions in way-finding, public graphics and signage that would come to brilliant fruition in his work for BART. And it allowed him to begin experiments with spatial narrative – moving visitors through a storyline and discovering the right scales and media to tell it with – that would make later exhibitions and display projects so compelling.

Extracted, with permission, from Architects and Artists: The Work of Ernest and Esther Born, published by The Book Club of California. You can listen to Nicholas’s talk about Ernest and Esther Born here.