Typology: A conversation

– Richard Hall, Hans van der Heijden and Andreas Lechner

In Spring 2025, Hans van der Heijden and Andreas Lechner corresponded about books which each had recently published that deal with the issue of ‘type’ and the role of drawing in typological work.[1] Hans invited Richard Hall to join the conversation, widening the discussion to three generations working in three different contexts.

The dialogue that follows took place in June 2025. It addresses questions of what typology is, its relationship to drawing, role in practice and teaching, and what its value might be in the architectural profession.

*

Typology

Hans van der Heijden (HH): What exactly do we mean when we use the word ‘typology’?

Andreas Lechner (AL): I understand typology as both an analytical framework and a mode of architectural reasoning—a way of thinking through design by comparison, classification, and critical interpretation. Types are not mere formal categories but collective spatial constructs: crystallisations of use, regulation, and socio-material habit that carry the sediment of shared norms and imaginaries. In this sense, types are not fixed models but mutable frameworks—open to reinterpretation and critical reuse. Read against the grain of contested histories, typology becomes a way to disclose how spatial forms embody and reproduce structures of power—how housing types codify domestic norms, how institutional types organise visibility and control. In a time of ecological and disciplinary exhaustion, typology offers not nostalgic comfort, but a form of resistance: it sustains architectural continuity without collapsing into repetition. It’s what I call ‘durable plasticity’—the capacity to transform while remaining intelligible, to be both stable and subversive—open to continual reinterpretation, redesign and reuse.

Richard Hall (RH): I agree but—in advance of assigning any value—I wonder if it can be put more simply. Isn’t it about inferring a series of basic formats by analysing and categorising a range of buildings with organisational commonalities? I don’t know if that’s the correct definition, but that’s how I see it.

What I’m curious about is the relay between how knowledge is gained and how knowledge is applied. I guess the former is typology and the latter might be about working typologically—or simply working with type?

HH: Typology has a didactic origin—and that is simultaneously the practical value of Quatremère de Quincy’s well-known definition.[2] If you say that a type has ‘no face’—that it is a building without properties—then it becomes more obvious where the other design layers—the stable architectural repertoire of geometry, grids, structures and material—are located in a project. In my mind, they are somewhere between the naked type and the actual material manifestation of that. Someone like Colin Rowe was great in his rational take on that stable repertoire in Palladio’s villas, but he did not actually talk about type.

Drawing

HH: When I tried to translate Quatremère de Quincy’s definition from French, it occurred to me how much he may have distrusted language. No wonder, given his Platonic view on type.

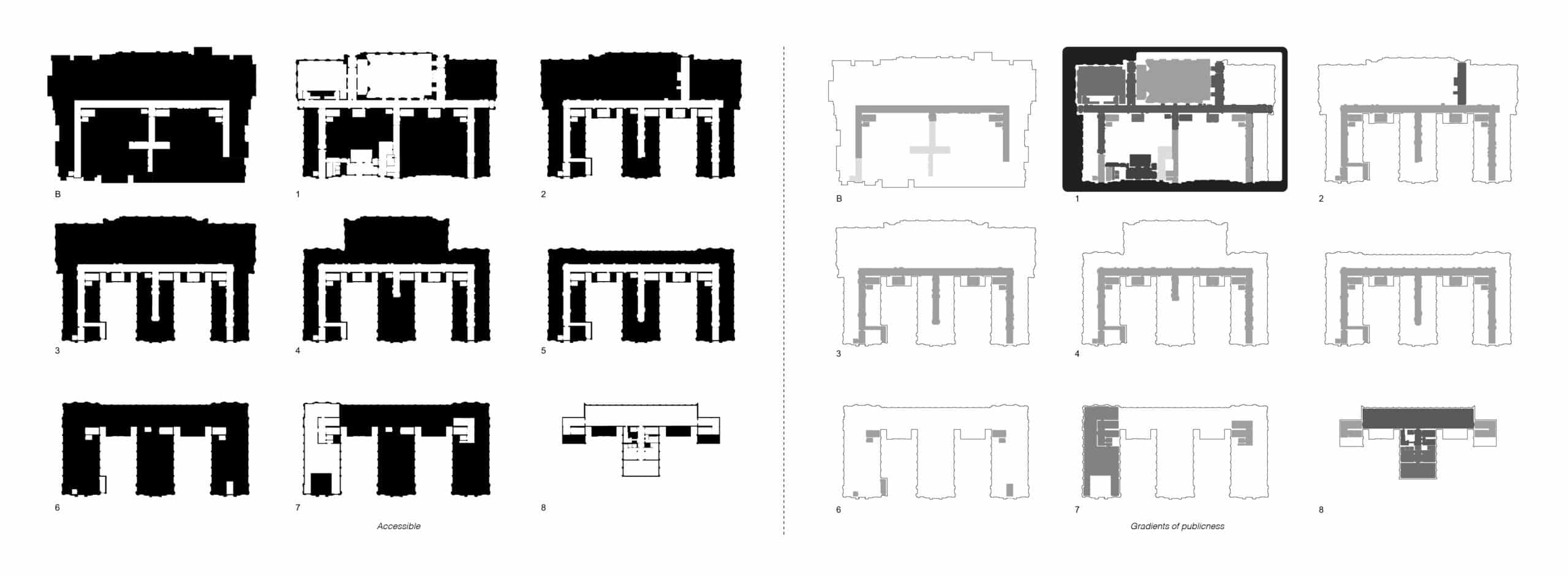

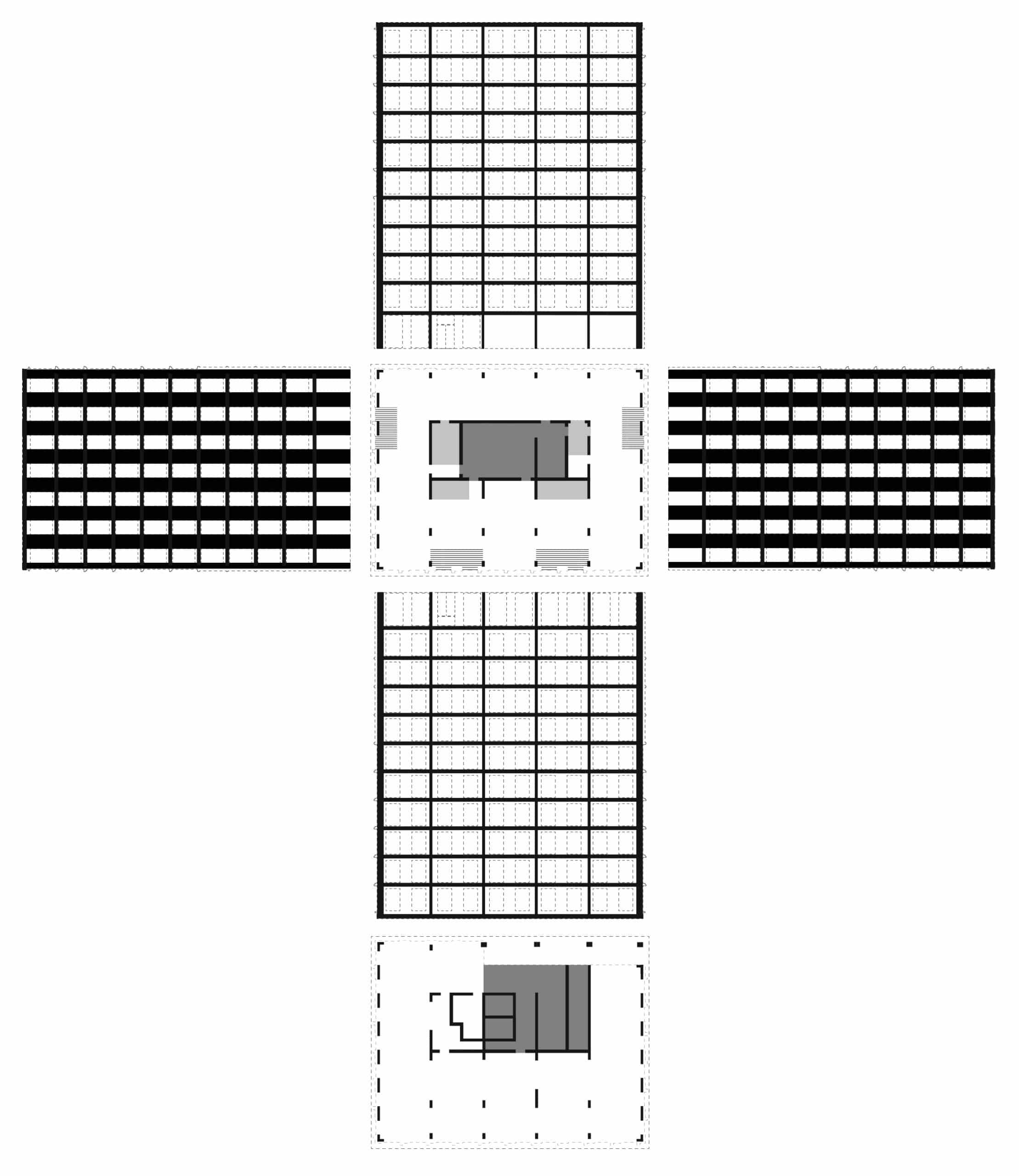

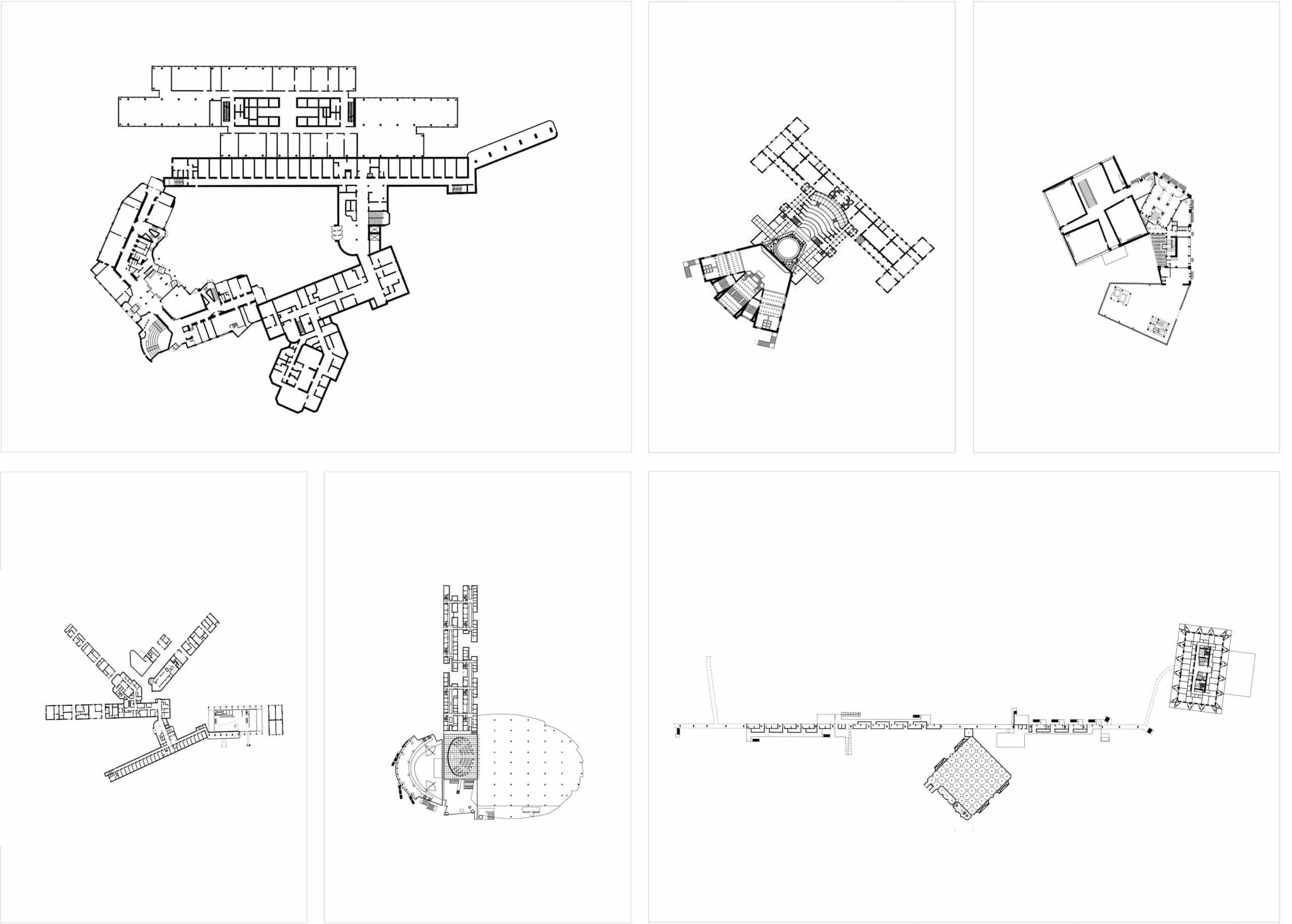

Drawing diagrams, in which the basic layout of a building is ‘charged’ by geometry, grids, structures and material, helps in understanding and communicating designs, and as such are instrumental in teaching and practice alike. By drawing, typology becomes part of a conscious management of architectural ideas and helps in establishing coherence amid the conceptual noise of design practice.

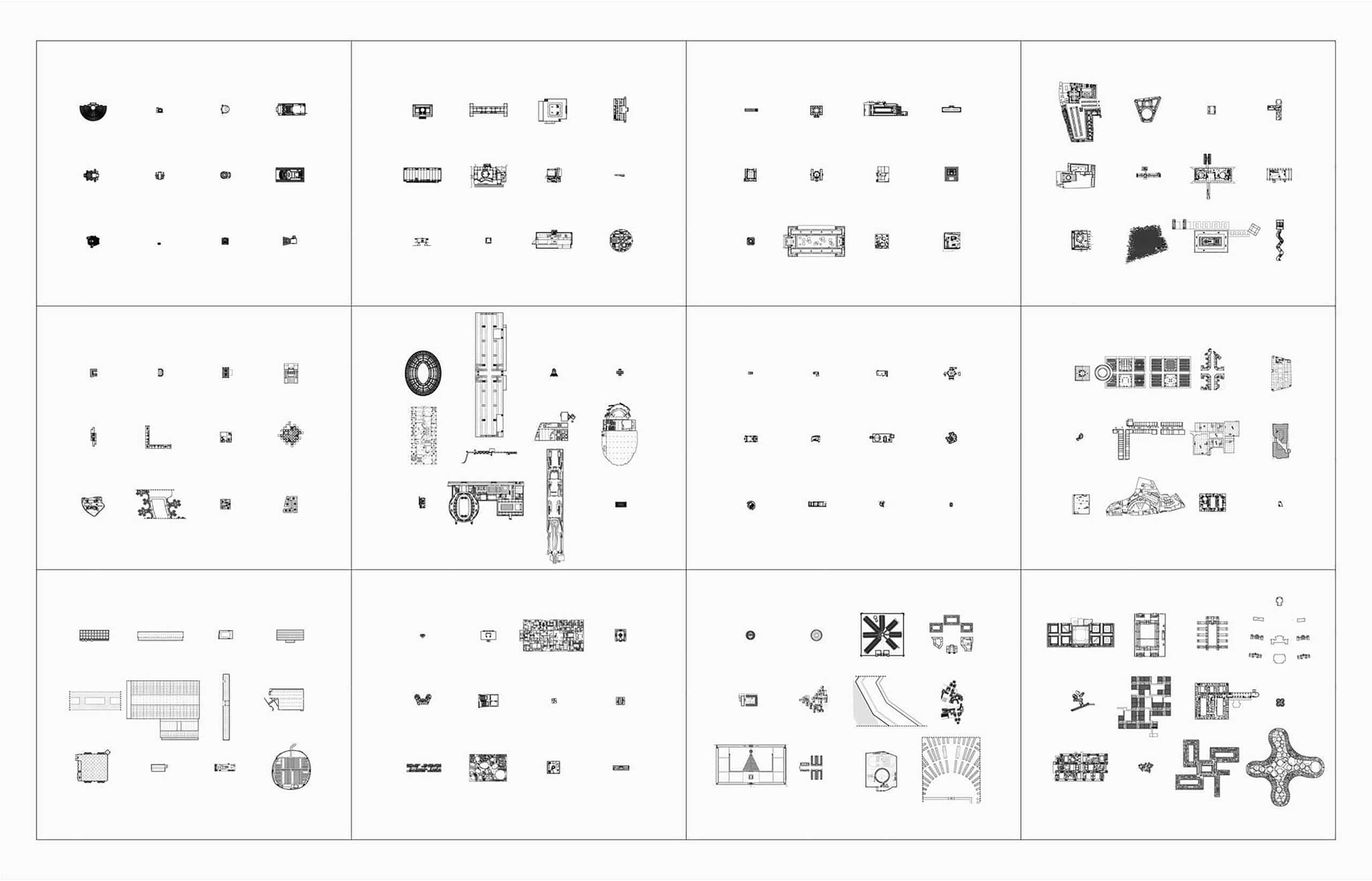

AL: This is why drawing plays such a pivotal role in architectural typology: it enables the abstraction necessary to compare spatial organisations across time, culture, and context. By deliberately showing less, the diagram reveals more—it distils generative principles and activates a network of possible spatial relationships. Through this explicit process of reduction and condensation, drawing transcends mere representation to become a mode of critique—a way of bracketing themes, shortcutting analogies, and foregrounding conceptual structure.

Plans, sections and axonometrics are never neutral; they are epistemic tools that construct spatial arguments and interrogate architectural hypotheses. In this sense, drawing functions epistemologically: it gives typology clarity and coherence not only through deduction or induction, but through abduction—an imaginative synthesis of fragments from which insight, design, and ultimately the architectural project may emerge.

It is in the act of drawing, above all, that the dialectic between norm and deviation, continuity and transformation, is most acutely staged—and most critically negotiated within the discipline itself.

RH: Good point. It’s interesting that—even with all the other sophisticated tools at our disposal—a simple, edited diagram is still the most effective way to analyse and convey the inner logic of a building.

It strikes me, as you’re both talking, that type is one of those things that can only be shown. It also strikes me—especially if one works with existing buildings or bits of city, where the typological base is unlikely to be pure—by making something like a typological diagram you can invest that artefact with the intellectual dignity of a type. Further, it strikes me that in many real-life situations you could make more than one diagram of the same artefact, meaning—depending on the ideas informing the analysis—you could typologically describe the same building in more than one way. Objectivity in the eye of the beholder.

Practice

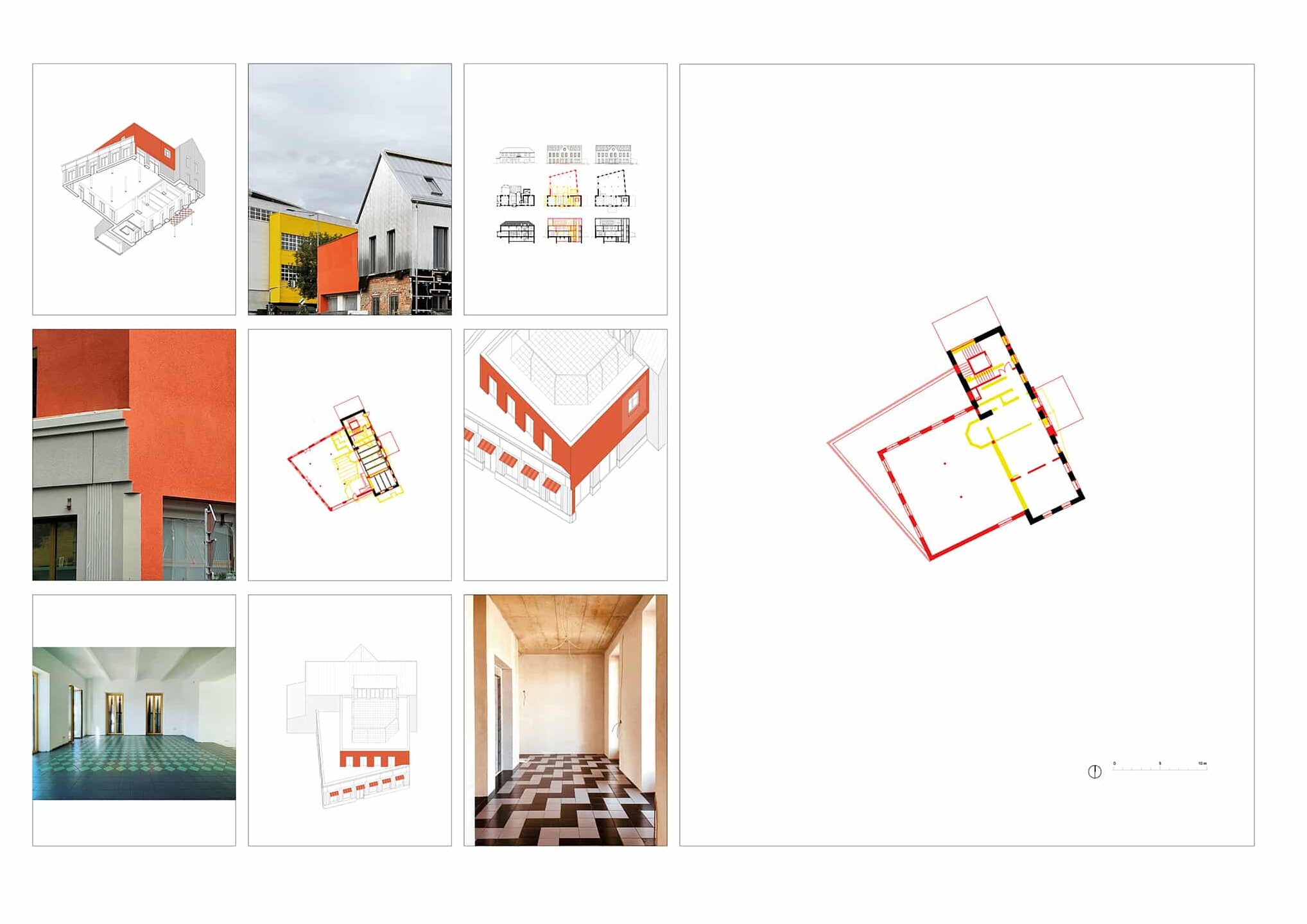

AL: Typology is a modest yet generative scaffold—a form of architectural reasoning that resists both the myth of the tabula rasa and the cult of singular authorship. It offers a mode of working with what is already there: with matter, with memory, with contingency. This approach resonates with Hermann Czech’s concept of Umbau—not as a secondary act of adaptation, but as architecture’s essential operation: building within, against, and through the existing.[3] Umbau is a form of conceptual maintenance that rejects novelty for its own sake, proposing instead a practice grounded in continuity, negotiation, and care. In this light, typology becomes both diagnostic and projective—a method for discerning latent affordances within the built environment and for imagining what kinds of collective life might be enabled through their transformation. It is a quiet but radical practice of revision, where architecture is understood not as invention ex nihilo, but as the thoughtful reworking of the familiar toward new forms of inhabitation.

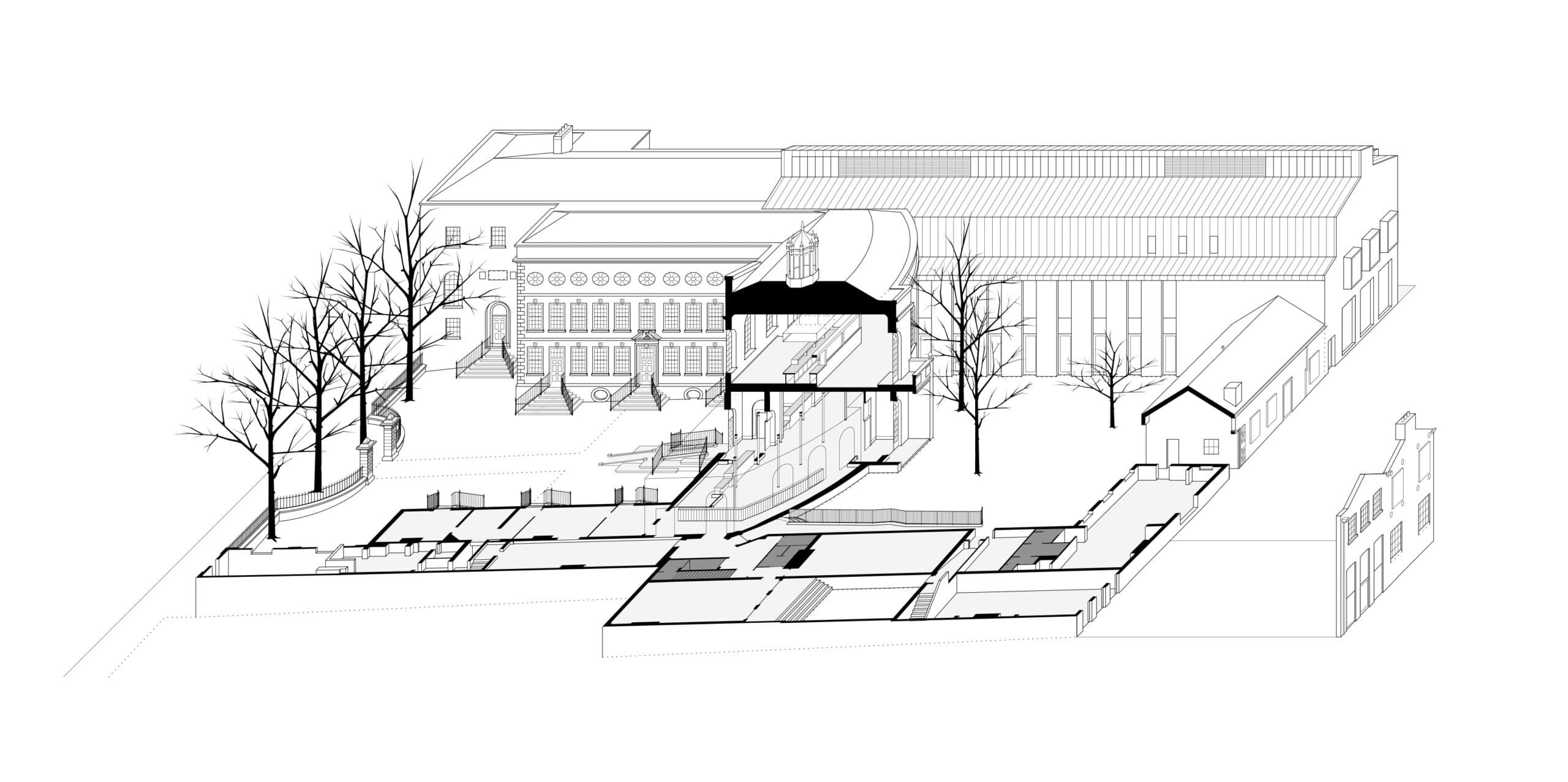

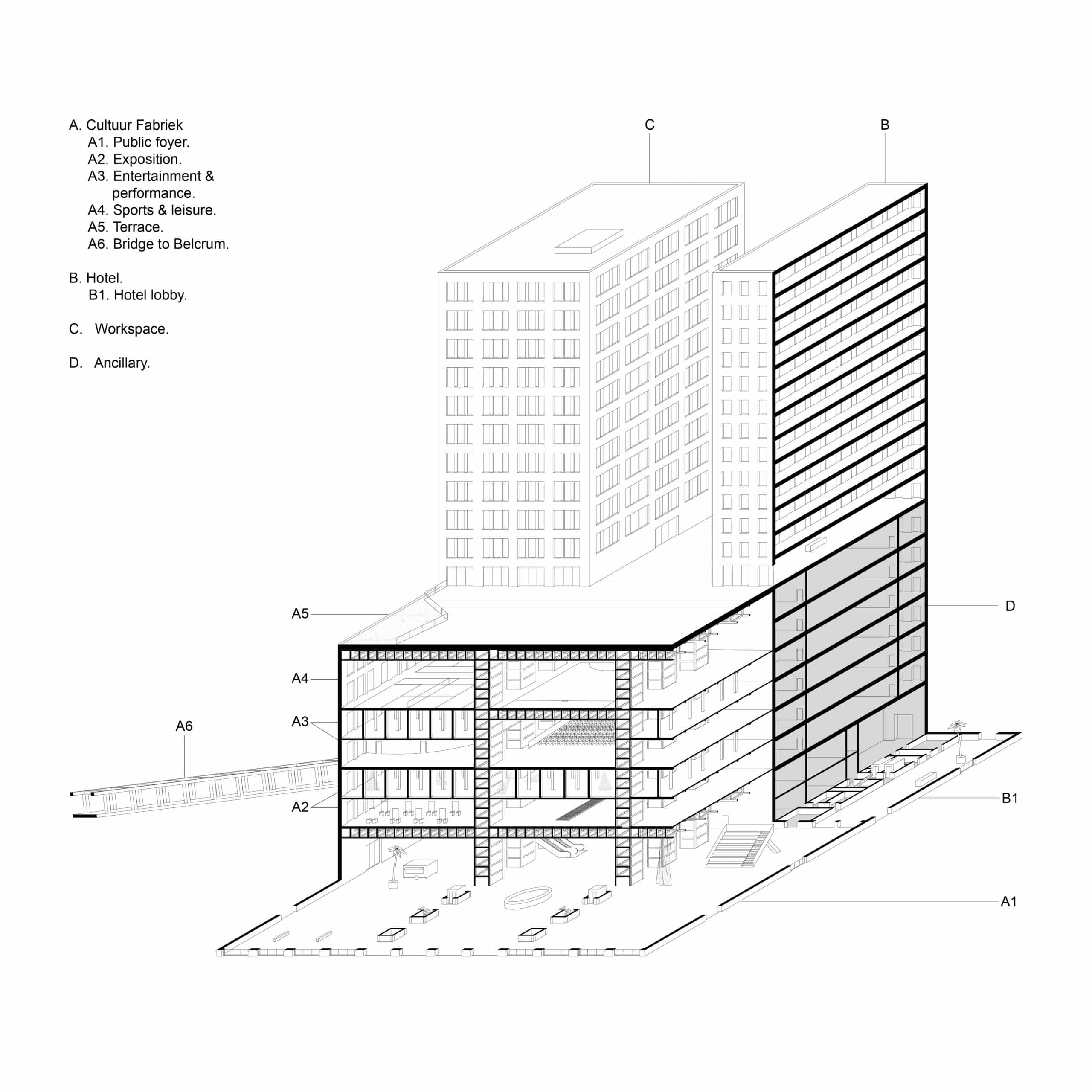

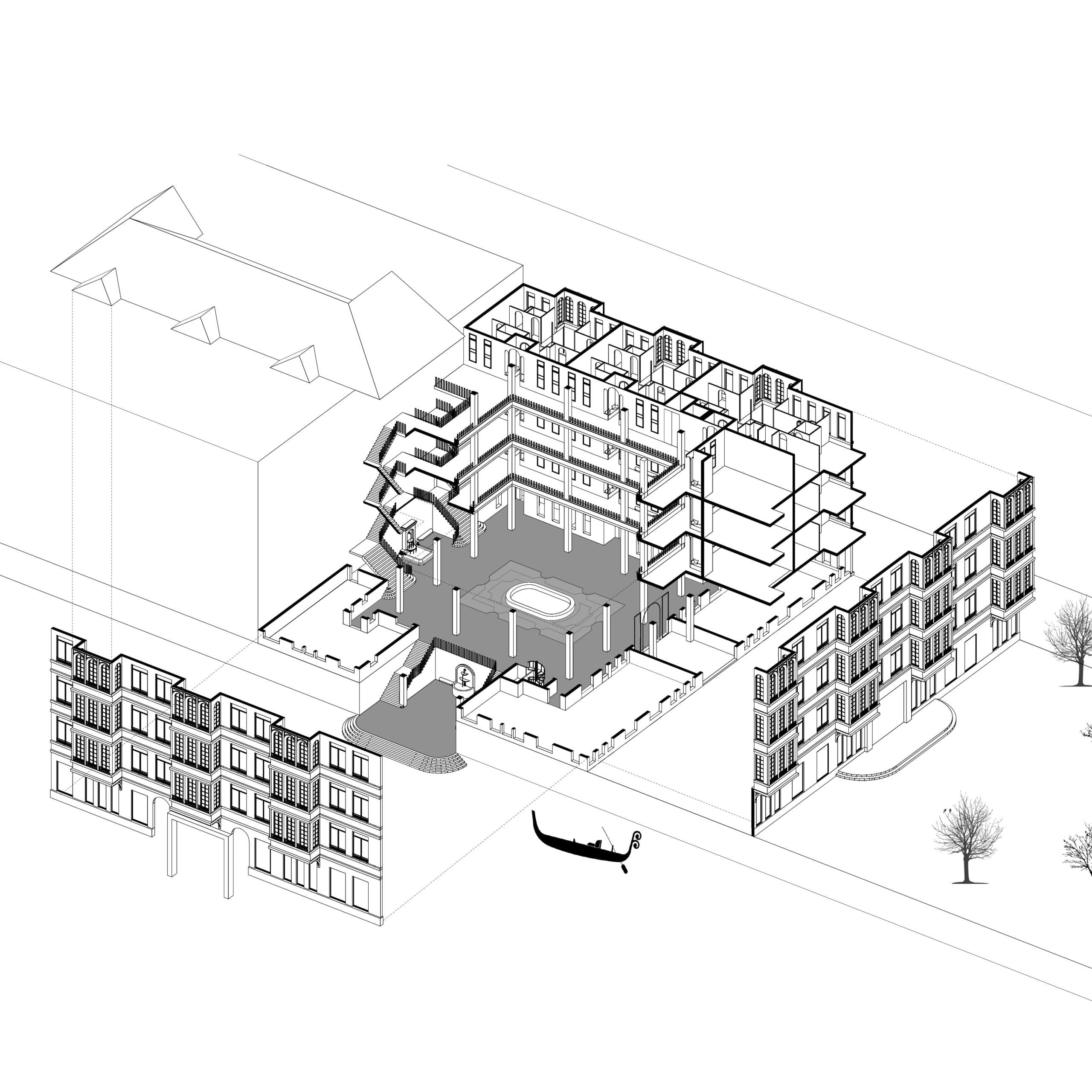

HH: Diagnostic and projective, I like that! When I think of the drawings I like to make—sketched diagrams that are investigative, complemented by cut-away isometrics in which type, and intuitive and stylistic choices are synthesised—ultimately, that is what we do as architects: analyse and synthesise by drawing.

RH: I have to make two confessions: I’m British and I work in London. Typology, in the way you both understand it, has never really been ‘hot’ in the UK. Indeed, anything vaguely resembling a priori knowledge—as distinct from an a priori image repertoire, it must be added—is treated with automatic suspicion.

Emma and I really stumbled into this by accident. We’ve always been unimpressed by two things: the reduction of the history of architecture to a form of taste-based connoisseurship, and the primacy of personal artistic intuition—as if being incomprehensible was a sign of genius. Our view is that the history of architecture is a history of ideas, and therefore these ideas—if they are not merely rhetorical—can be analysed in the buildings. Similarly, if architecture is a public profession, it is not unreasonable to expect its practitioners to be able to explain ‘the thing’: what is it? Why is it like this? Why this and not that?

So, it’s also a way of keeping oneself in check. The same analysis we apply to examples can be applied to our own work during the design process to test the inner consistency of a proposal. It’s a combination of insatiable curiosity and self-criticism.

Teaching

HH: In teaching, I initially try to disconnect objective typology and the fuzzy world of inspiration and good intentions. We live in a world in which ‘the reference’ seems to rule. When students show a reference, it is not always clear which aspects of their example are actually interesting and useful. They often copy the whole thing, including its ideology and intentions. Typology and the awareness of the layered nature of architectural composition, help to synthesise items with various modes of stability and permanence in a design, and to resist the resampling of references in a mere collage.

RH: Like Hans, we don’t think students learn very much by collecting random pictures of buildings. What we hope to share with our students is a super practical way of analysing what a building consists of. I don’t mean this in a ‘construction 101’ sense, but rather in terms of understanding why this building, based on these ideas, is organised in this way, using these means.

We tend to ask students to design a building without any one fixed use but with explicit urban intent. This lack of occupational certainty means that students cannot simply copy a decent housing or office plan, but are put in a position where they need to think very carefully about the implications of a building format—an organisation—in terms of what kind of life it supports or limits.

They also have to deal with the relationship between generality—in terms of use—and the specificities of their site. Students quickly discover that this operation is not as simple as it sounds. The synthesis of these givens—a specific, compromised site and a general-purpose building—tends to yield extremely surprising results. Inevitably, they find themselves studying a very wide range of types as the basis for their experiments.

AL: You describe not a straightforward transmission of knowledge, but the cultivation of architectural intelligence—a way of reading the built world as a layered text marked by tension, repetition, and deviation. For me, typology is a means of grasping spatial and programmatic difference. A single-family house and a civic institution respond to fundamentally distinct needs, yet both belong to broader genealogies that recur, transform, and sediment across time and culture. Typology allows us to engage these lineages critically—not to replicate inherited forms as real-estate clichés, but to reinterpret them through the lens of contemporary use, ethical concerns, and evolving constructional logics.

Typological thinking thus carries both disciplinary memory and critical agency. It asks: what forms of life do these structures enable or foreclose? What histories do they invoke—or resist? What patterns of social encounter do they afford? As such, typology becomes a method of inquiry mediating between tradition and invention, between contextual specificity and shared architectural intelligence.

I often begin with what I call productive ambiguity: diagrams that destabilise as much as they clarify, comparisons that provoke through estrangement rather than resemblance. Precedents are not models to imitate but texts to be re-read—their logics exposed, their potentials speculated upon. We learn to draw not merely to represent, but to critique and project: to identify affordances and to imagine futures structured through use, form and cultural logic.

This approach may align with Pier Vittorio Aureli’s idea of Absolute Architecture, yet it diverges from its monumental austerity.[4] I favour the strange and peripheral—not for exoticism, but for the insights found in difficulty: parking garages as theatres, supermarkets spliced with housing, derelict halls revived as civic devices. These are neither formally heroic nor easily consumed, but they teach with wit, perhaps with a touch of Dada—as Richard reminded me—where surprise becomes a critical tool, and estrangement a mode of pedagogy. If the typical teaches by precedent, the counter-typical teaches by rupture. I prefer to rely on both.

Value

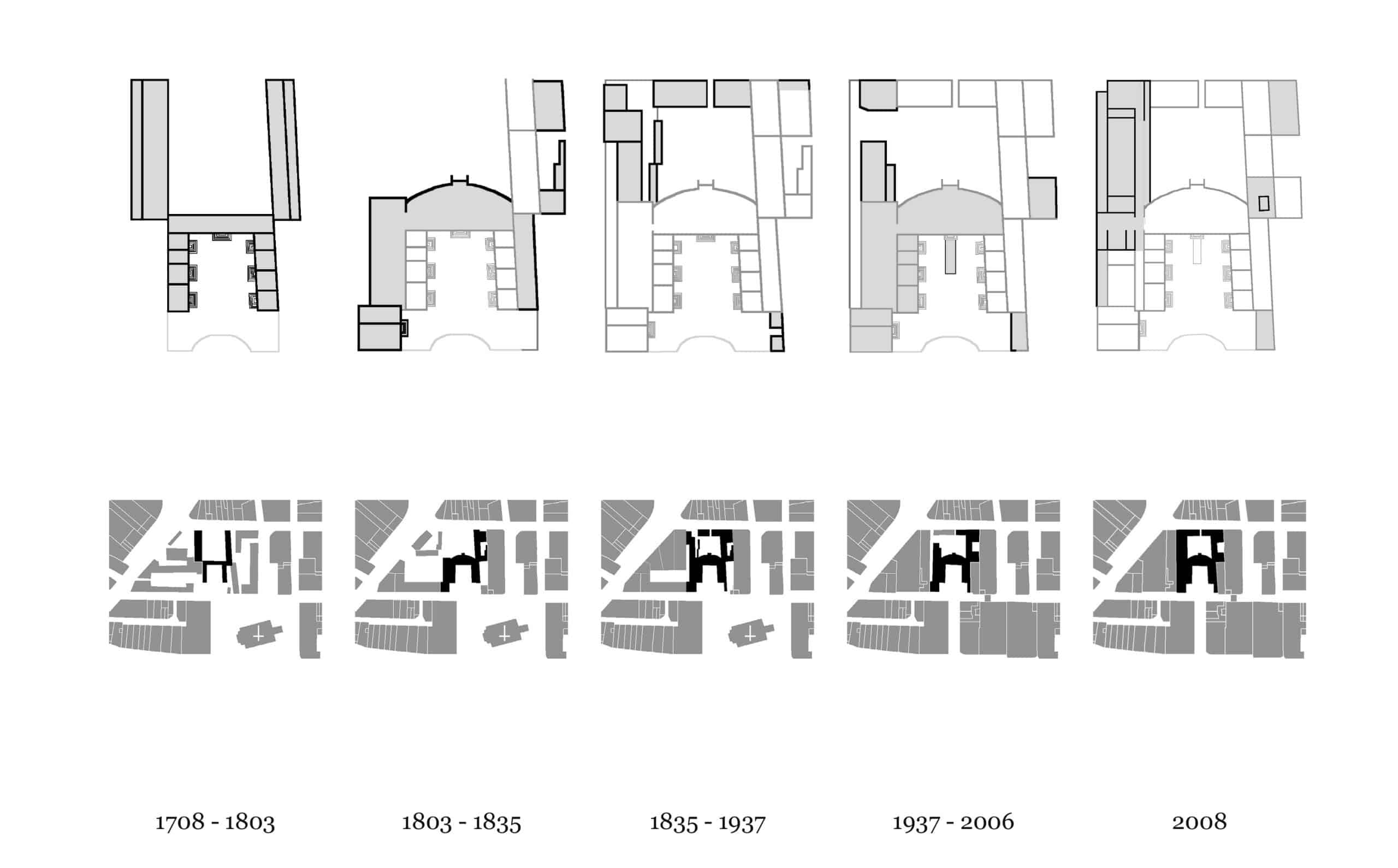

HH: Andreas, like Colin Rowe’s writing, to me, your book seems somewhat underdefined in typological terms. I take it that you use the term ‘type’ for anything that is stable in a building. Your book strongly suggests that that particular typological realm is a territory of design investigation. Within modern tender procedures such research precedes the actual design stages. I read your book not just as an attempt to questions that established practice, but also to disturb the unagreed consensus on what is currently labelled as ‘adaptive re-use’.

Today, one of the examples in your book, the transformation of the ancient Porta Decumana gate type into a palazzo type, has become inconceivable. It is not that heritage specialists would not allow that. It is even worse: they proactively make such thinking impossible through tender criteria. Those offices that acquire their work through tenders, gladly jump through the hoops that specialists hold up for them. And, again, perhaps understated by Andreas, I think that his use of the word Umbau is radical and programmatic, compared with contemporary attitudes to adaptive re-use, which tend to lack architectural awareness.

You like to say that architectural conversation has never been so pleasurable. Yet, just like in politics, my feeling is that Cartesian observations are needed more, and not less.

AL: Perhaps the provocation of Umbau as a timely mode of architectural reasoning—at once historical and open-ended—has not yet been made fully explicit. My intention, however, is clear: typology offers continuity not as comfort, but as resistance. It preserves shared spatial logics without collapsing into arbitrariness and insists on limits—not every use fits every form. It demands a careful reading of how form affords, resists or generates inhabitation. Seen this way, architecture is a condition—an open, situated practice of transformation. If typology helps us think architecture otherwise, it is not as product but as practice, not as prophecy, but as an attentive engagement with the world. It reframes design as a form of critical care—for history, for context, for the public and greater good, and for the futures we cannot yet predict. Umbau is not a technical supplement. It is a political and ethical stance—architecture’s internal critique. It resists the superficiality of trend-driven reuse and instead calls for a deeper, slower, and more generous engagement with the spatial structures we inherit—and must now rethink.

RH: Until you invited me to this discussion, I wouldn’t have considered our work especially typological. So, from our side, the value of it resides in the basic reasons we’ve been doing something like it without knowing it: a desire to see, think and communicate clearly, and—more than anything—to extract latent potential from things that already exist.

My plea would be not to think of typological work as something heavy. It’s not about truth or ‘speaking with the dead’. The pleasures Andreas is describing require discipline and method, but also an open mind. Before we started, you mentioned someone saying something like, ‘Typology isn’t about the past, it’s about having options.’ For us—if it turns out we’re not imposters in this discussion—typology is really this pragmatic.

HH: Richard! You might be the only real typologist in this discussion…

Notes

- See Hans van der Heijden, Het woonpalazzo – The Residential Palazzo (Amsterdam: HvdHA, 2025); Architectural Affordances – Typologies of Umbau, ed. by Andreas Lechner, Gennaro Postiglione, Francesca Serrazanetti, Maike Gold (Naples: Thymos Books 2025); and Andreas Lechner, Thinking Design: Blueprint for an Architecture of Typology (Zurich: Park Books, 2021).

- As Quatremère de Quincy famously argued, the architectural notion of type is not to be confused with the model. Where the model is an object to be replicated, the type is an idea—a generative principle, abstract yet operative: ‘The word type presents less the image of a thing to copy or imitate completely, than the idea of an element which must itself serve as a rule for the model. […] The model, understood in the sense of practical execution, is an object that should be repeated as it is; contrariwise the type is an object after which each artist can conceive works that bear no resemblance to each other. All is precise and given when it comes to the model, while all is more or less vague when it comes to the type.’ Quatremère de Quincy, ‘Encyclopédie Méthodique, Architecture, 1788–1825’ in The True, the Fictive, and the Real: The Historical Dictionary of Architecture of Quatremère de Quincy, trans. by Samir Younés (London: Andreas Papadakis Publishers, 1999), 254–255.

- A working definition of Umbau, as discussed by Hermann Czech, understands ‘transformation’—the broad translation of the German term—as encompassing all forms of architectural adaptation, from minor alterations to major conversions, renovations, and refurbishments. For Czech, Umbau is not secondary to design but its very essence: a foundational operation grounded in existing conditions and ideas. This leads to his often-cited insight that ‘in essence, everything is transformation.’ His conception of Umbau is thus inseparable from a broader architectural ethos marked by the refusal of the tabula rasa, a sensitivity to use, and a resistance to heroic or ex nihilo invention. Rather, Umbau signals an attentive, situational and sometimes mannerist engagement with the city and its architectures—a mode of conceptual maintenance that is neither nostalgic nor reductively functional. See Eva Kuss, Hermann Czech – An Architect in Vienna (Zurich: Park Books, 2023).

- Pier Vittorio Aureli’s The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture reclaims architectural form as a political act of resistance, grounded in autonomy and the etymological sense of ab-solutus—that which is detached and conceptually sovereign. Against the backdrop of neoliberal urbanisation, Aureli critiques architecture’s complicity with process-driven and participatory paradigms, insisting instead on formal clarity as a means to assert architecture’s critical agency. See Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011).

Richard Hall (Leicester, 1985) co-founded General Office with Emma Rutherford in 2023. Hans van der Heijden (The Hague, 1963) co-founded biq with Rick Wessels in 1994 before establishing his own office, Hans van der Heijden Architecten, in 2014. Andreas Lechner (Graz, 1974) is an associate professor at TU Graz and started his own office in 2011. They are all active in practice, research and teaching.