Useless Terrain: The Ballynagrenia and Ballinderry Bog

Every hectare of drained peatland emits two tonnes of carbon a year. Known peatlands only cover about 3% of the world’s land surface, but they store at least twice as much carbon as all of Earth’s standing forests. Cutting turf for fuel has been practiced for centuries, and communities have established a strong cultural identity through turf cutting. Today it is estimated that 100,000 households in Ireland use turf for heating.

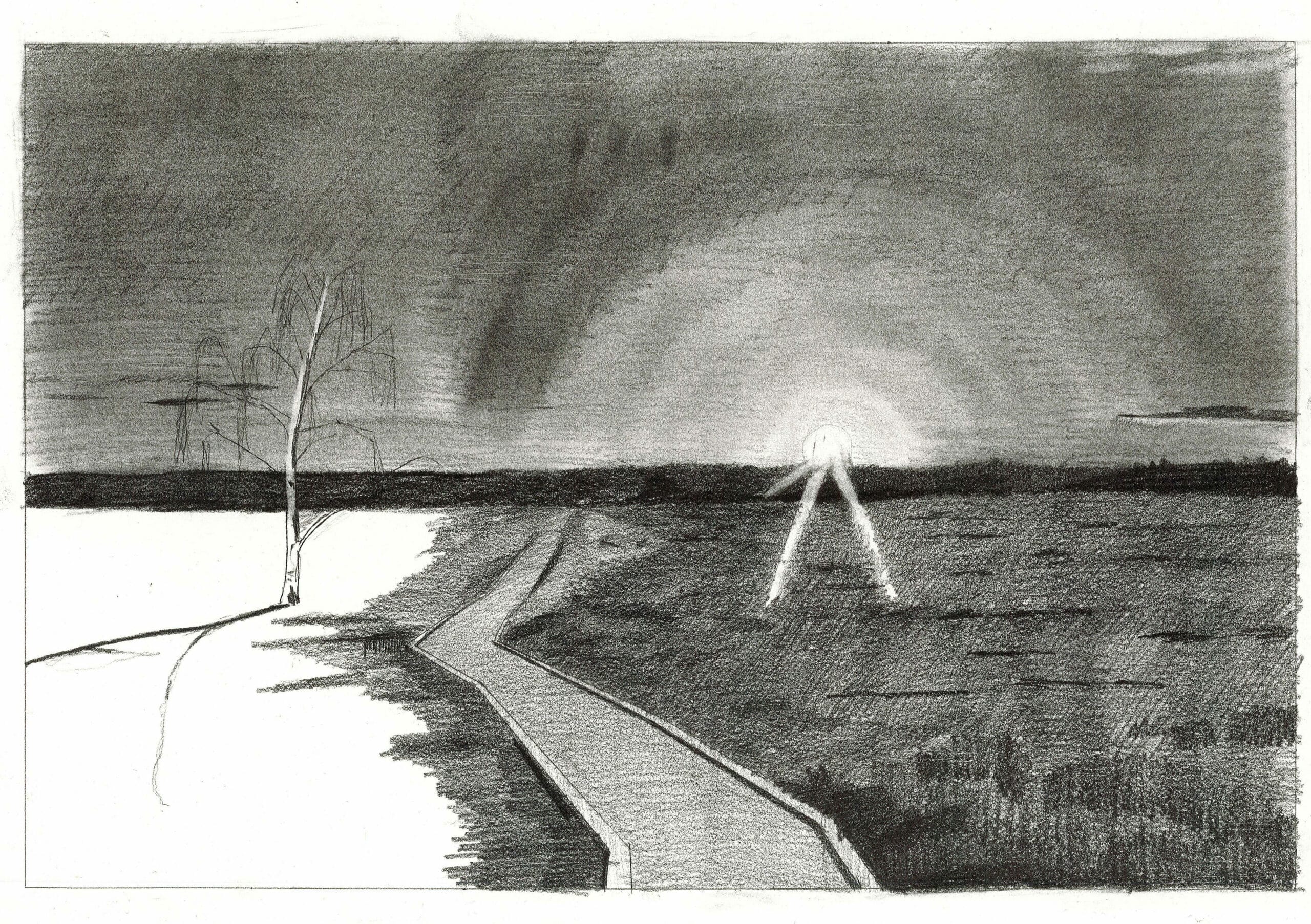

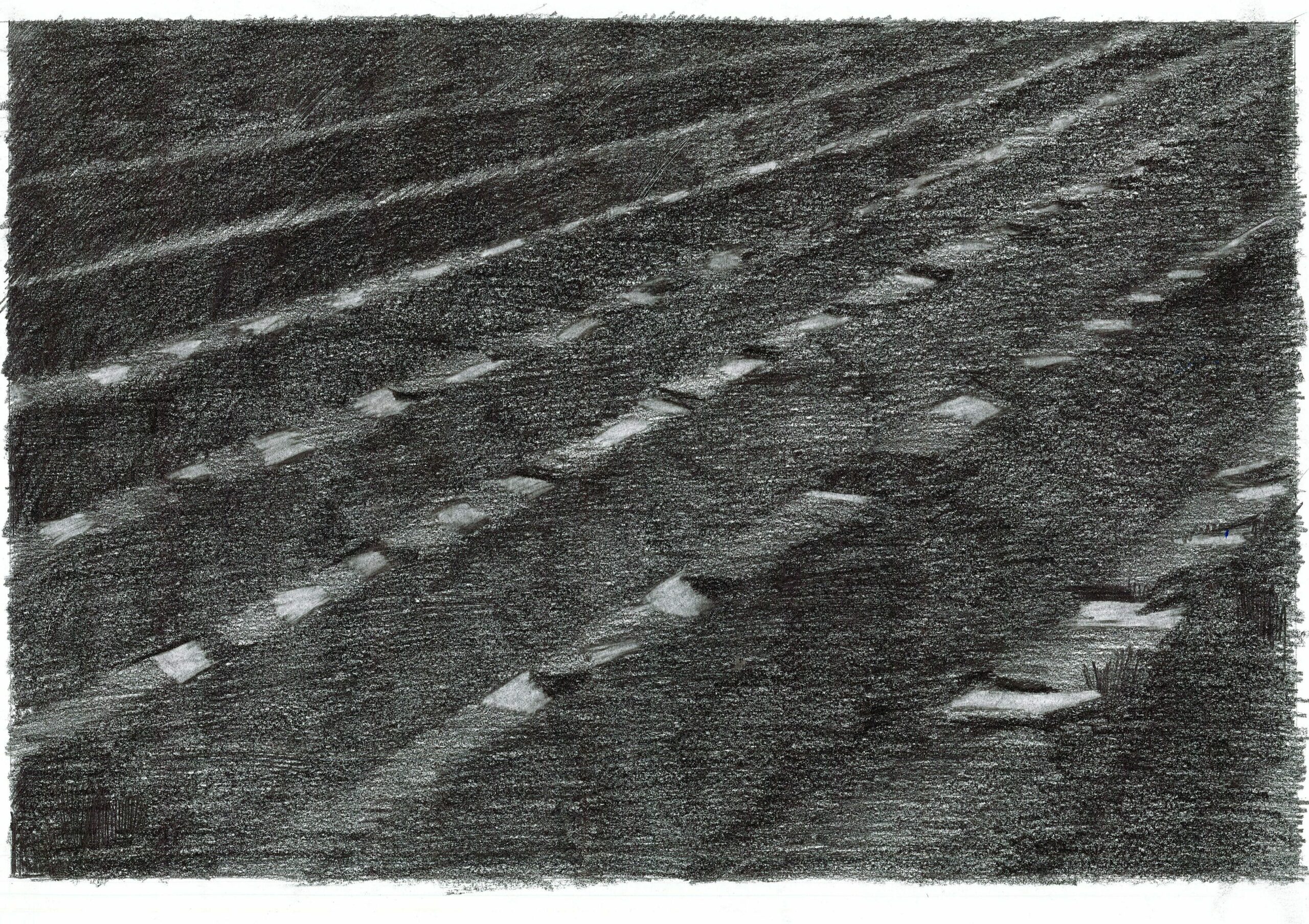

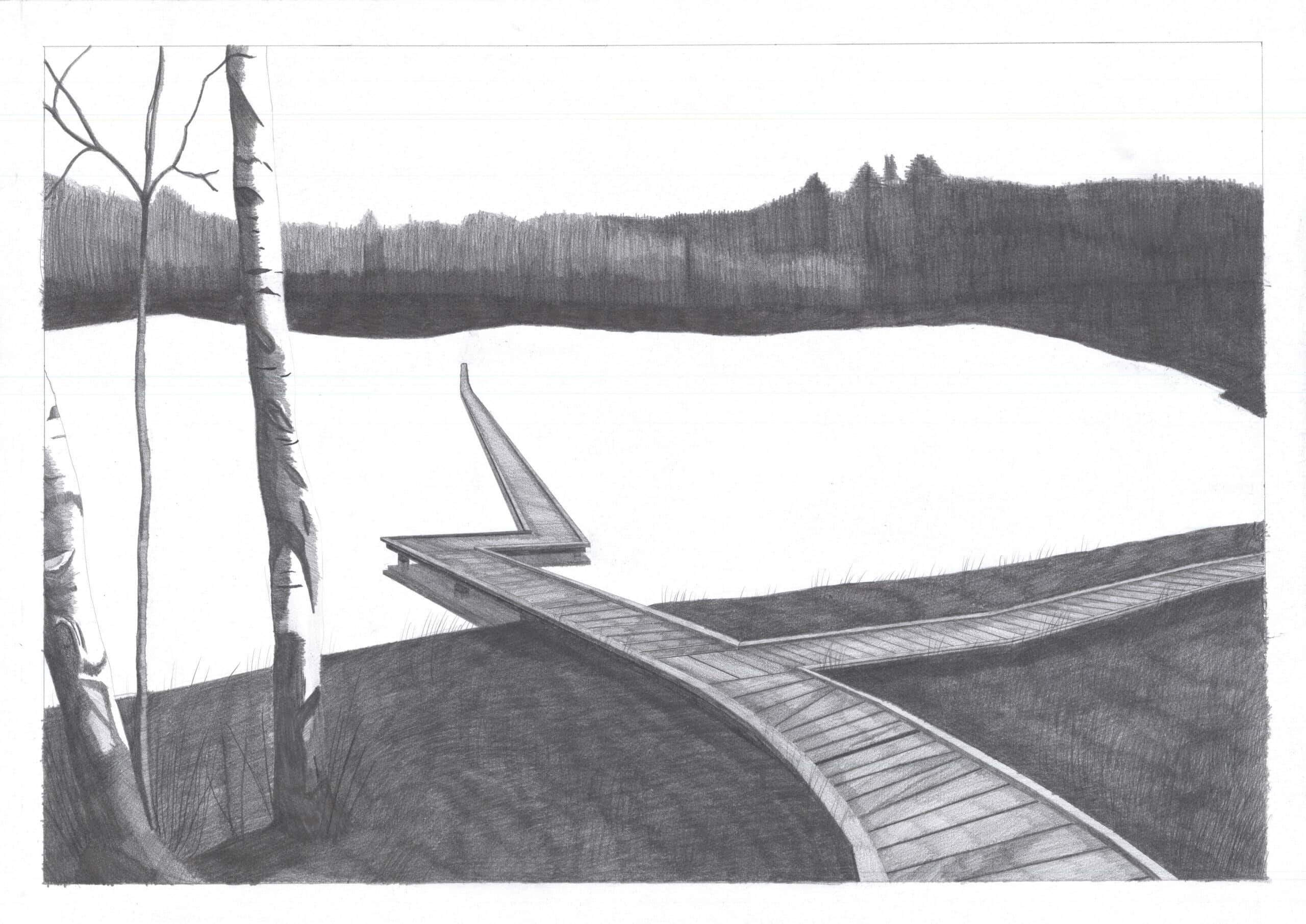

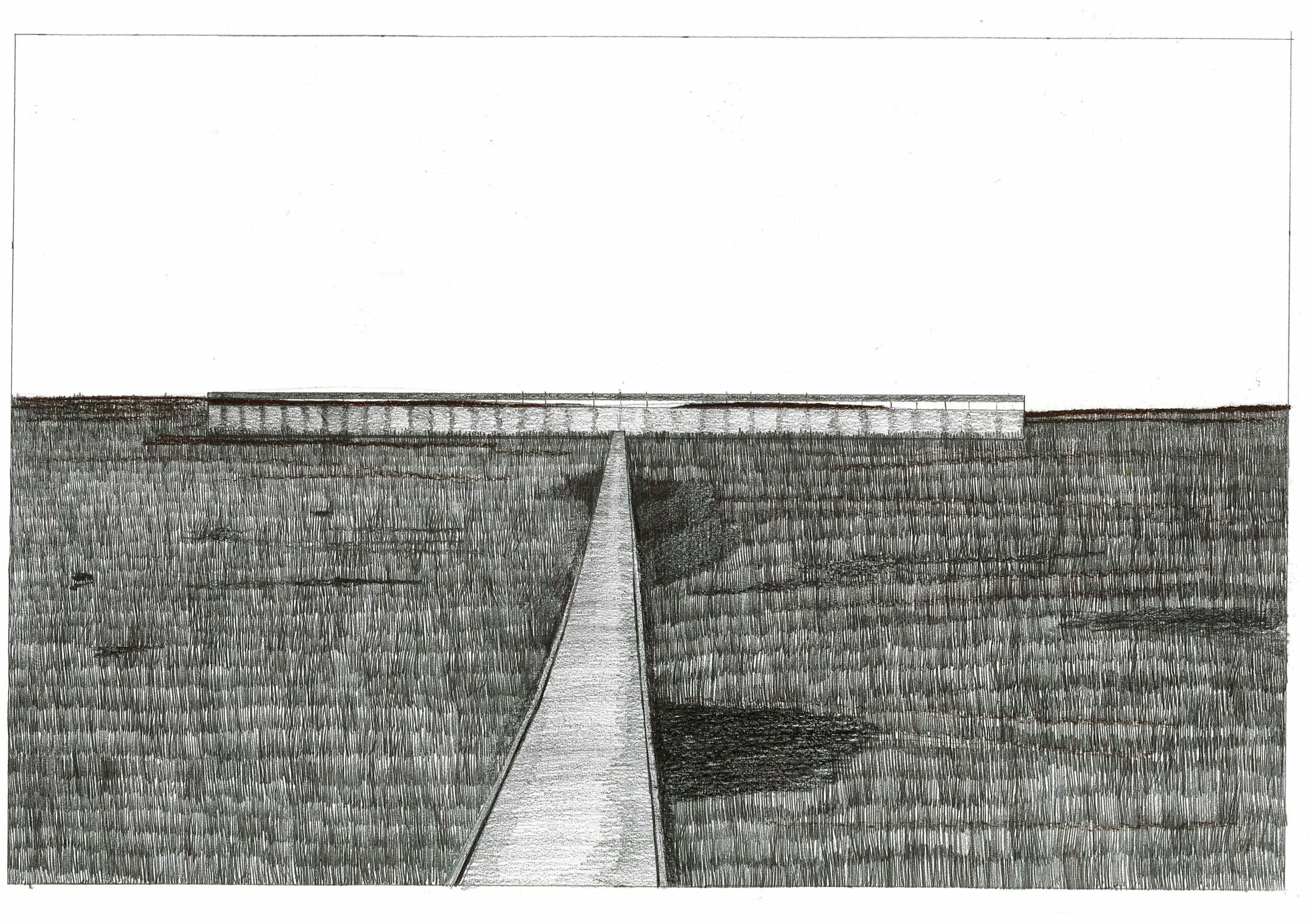

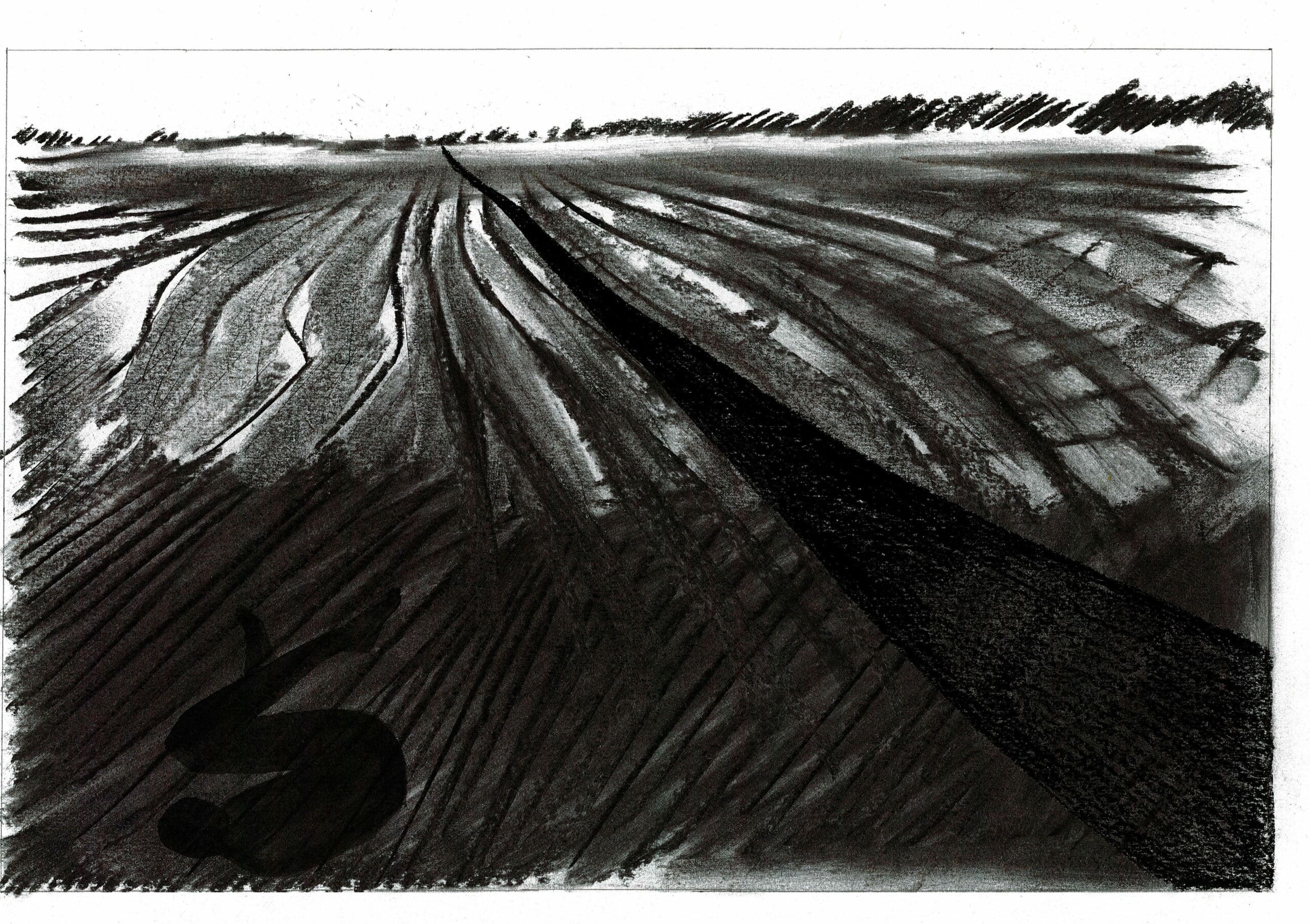

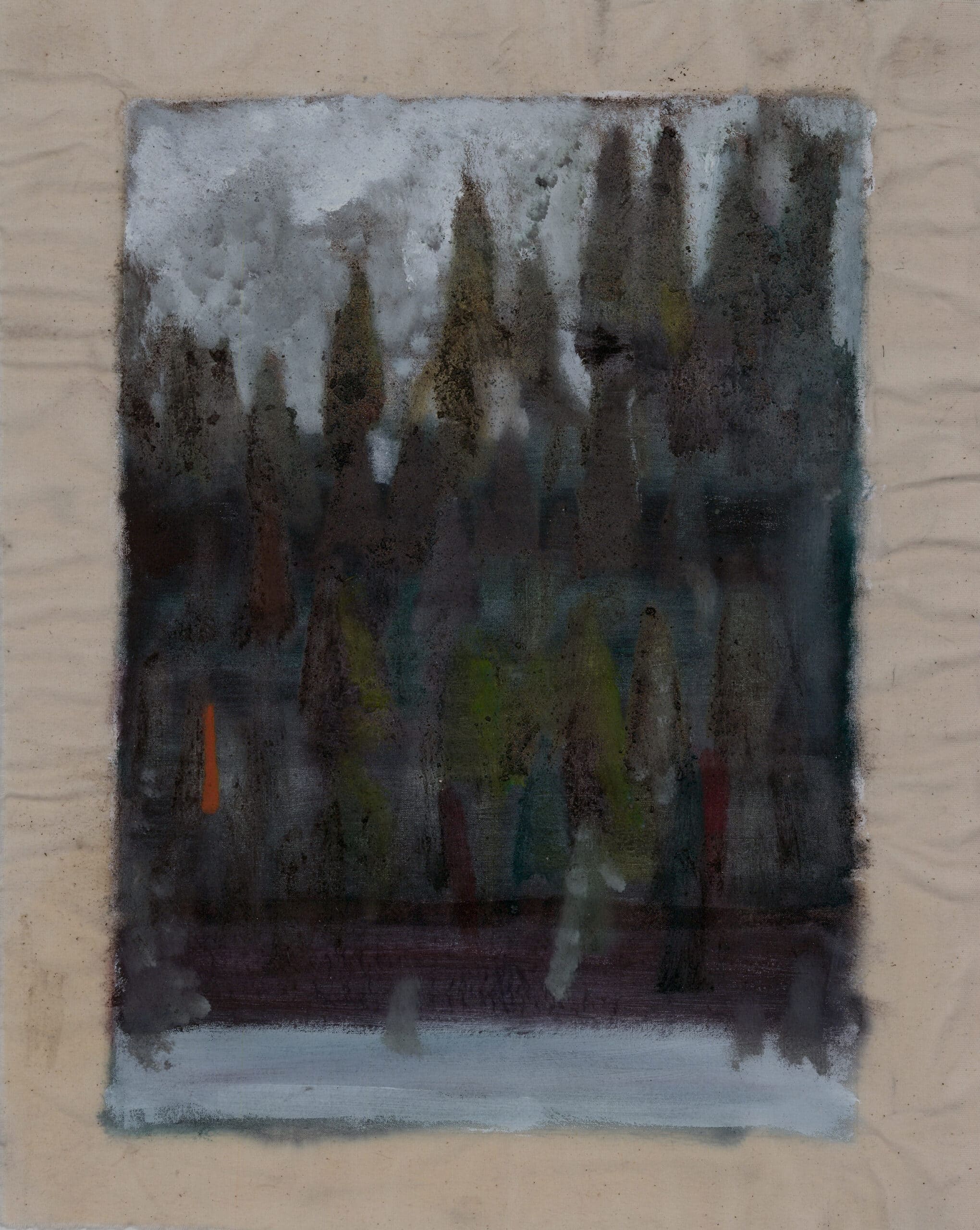

Useless Terrain is a project that proposes a new form of cultural tradition, one that provides communal care for the local ecosystem. It explores the exhaustion of turf in rural Ireland, focusing on hyper-industrialised land and the productivity of a vital ecosystem. It is a holistic restoration of the Ballynagrenia and Ballinderry Bog in County Westmeath, designing a walkway that determines a 10,000-year journey around the bog, as it ever-so-slowly repairs itself from violent colonial and industrial scarring. The project is told through a conceptual drawing practice that waits, watches and records the return of this vital ecosystem. The consistent drawing process navigates the unrelenting passing of time and the steady moving and breathing of the bog alongside a ten-kilometre boardwalk that determines a new relationship and ritual the people have with the terrain. I believe there is a strong connection between the passing of time, the layering, observation, storytelling and mark-making that embodies the bog. The drawings also show a personal relationship to the bog: the work has been drawn by my own hand as opposed to a machine. The illustrations tell a story. I wanted to speak to the storytelling culture embedded in Ireland and the boglands. I looked at many iterations of bog storytelling: old folklore stories, myths and legends, and modernist poets such as Seamus Heaney. Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot strongly characterised the project, expressing itself in the monotony of waiting bog restoration requires and the human relationship to the land. In Waiting for Godot, we, the audience, are hopelessly hopeful for a resolution to a problem that seems beyond our grasp; this reading of Beckett is much like our relationship with the bog, the vast breadth of time restoration seems a futile endeavour. Re-drawing the land seems to perpetuate this hopeless hopefulness.

Joseph Heffernan is an architecture student at the Royal College of Art. You can see more of his work on the RCA’s online Graduate Show 2022.

– Eric Parry and Robin Webster