Vor-textu(r)al Translations from Building to Drawing

Exploring the Interval

Architecture emerges somewhere in the interval between the first mark of drawing and building; it is from this interstitial space that potential stirs, waiting to be swept up in bouts of differential combustion. In this sense, architecture is neither drawing nor building but something that exceeds both, while transforming their mutual relation as well as their individual nature. It is no revelation that their co-operative relation has been the topic of much speculation, but the issue has inclined more heavily in the direction of drawing to building, since built form is usually an end in itself. This article presents experimental work that attempts not so much to reverse this directionality per se—as it was established by Robin Evans in his seminal work Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays (1997)—but to foreground the possibility of thrusting the relation between drawing and building into eternal returns that generate new qualitative-relational tonalities at every (re)turn of the architectural process.[1]

One may be familiar with Pliny the Elder’s story of Dibutades, which traces the origin of drawing back to the outline of a departing lover’s shadow on a wall. In ‘Translations from Drawing to Building’, Evans elucidates his comparative interpretation of two representations depicting this story. He compares the paintings of artist David Allan and architect Karl Schinkel, both entitled The Origin of Painting, to illustrate the foundational difference between the (classical) role of drawing for the painter and the architect, respectively. His argument rests on the pictorial disparity between the architectural (interior) context of the former and the pastoral (exterior) context of the latter. In Allan’s painting, Dibutades traces the outline of her lover’s shadow, projected from a lamp’s point-source illumination on the wall of a room. In Schinkel’s rendition, the shadow of the lover’s profile, traced by a shepherd on the face of an inclined rock, depicts the projection of the sun’s parallel rays.

What Evans endeavours to demonstrate in this comparative analysis is the ‘reversed directionality’ of drawing, of a representation to its object, which he claims establishes the fundamental difference between the artist’s and the architect’s vision. In one scenario, the artist (Allan) chooses an architectural surface as support on which to inscribe the first mark of drawing and an interior built setting to illustrate its origin, thereby foregrounding the precedence of architecture over drawing. Architecture is here prior to representation. In a second scenario, the architect (Schinkel) selects raw matter (the face of a rock) as the surface of inscription, thereby tracing the initial mark directly on ‘nature’ and emphasising the precedence of drawing, as a prior act of thought, over building. Architecture is here consequent to representation. The artist’s drawing, accordingly, depicts the reflection of a reality that exists outside of the drawing itself, whereas the architect’s reflects a reality that exists only within the drawing until it is projected outside of itself and concretised. In either case, drawing is a function of projection, and both renditions in Evan’s view involve all the required elements of drawing: a source of light, an object or subject of representation, a surface of projection and a means of tracing.

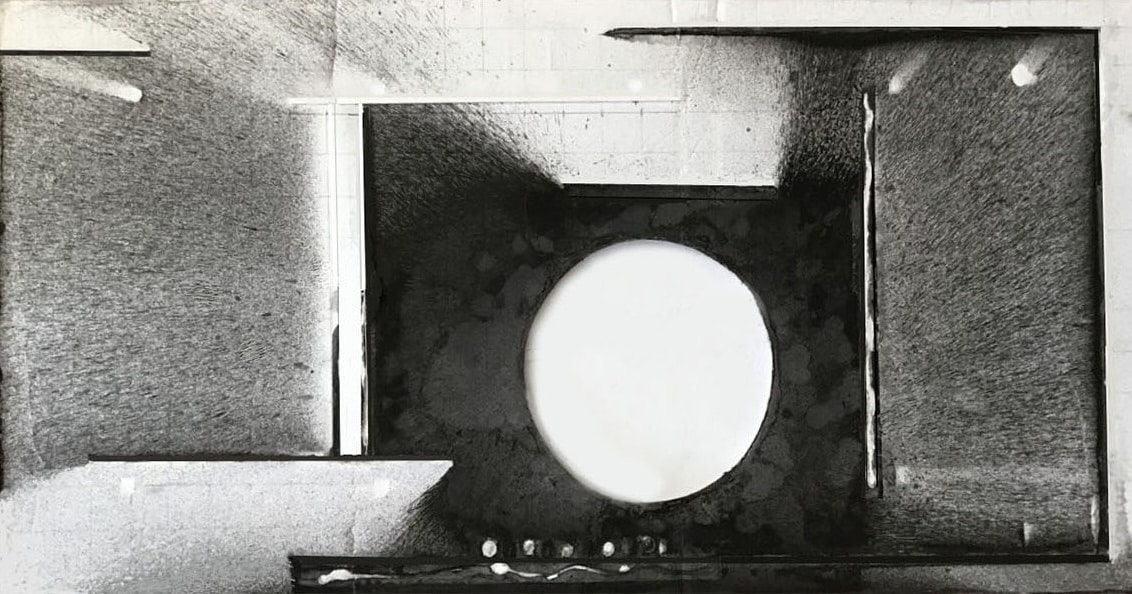

The project Vor-textu(r)al Translations from Building to Drawing seeks to inflect the vectorial directionality Evans has put in play between drawing and architecture by changing the nature of its source of projection and tracing, and thus challenging the role of architecture in the dialectic. The source of unidirectional light is replaced by a source of vortical airflow, and the hand or means of tracing, by the blades of a mechanical propeller. The project was first explored through a series of improvised architectural models of two simple inverted interior spaces mirroring each other back-to-back across the same floor plane. In other words, one space was upside-down directly beneath the other so that the common floor surface between them became a sort of reflective plane. A basin of China ink in an alcohol compound was alternately placed on the floor of either space, and a small propeller was set in motion and lowered onto its surface. The ink was propelled and pulverised across the space, leaving negative shadows of architectural elements and streaks of centrifugal airflows on its walls (Fig.1). The model was then turned upside down, and the action was repeated in the second space. The wall surfaces of the model were subsequently unfolded and deployed into a continuous linear panel constituting a pictorial surface with an inscription of the space of internal elements—the traced shadow was no longer that of its object but of the space it activated.

What ensued was a gently curbed longitudinal archiscape that evoked an atmospheric ‘landscape’, embodying the vortical energy of the event of drawing-with architecture (Fig.2). One might even argue that the floor-line become-horizon reflected a reversible gravitational field around its axis that evoked another reality. Regardless, Evans’ drawing-building and interior (architecture)-exterior (nature) dialectics seemed to come together, blurring and activating the interstice that had set them apart. The two visions attributed to the artist and architect were reconciled in the production of (atmospheric) surplus-value. The activated space of architecture had been projected into drawing and simultaneously onto its own architectural surfaces. It both produced (and was the pictorial product of) a drawing which pointed to an outside (archiscape) while virtually bringing inside-out and onto its surfaces in a new relation-scape. An atmospheric aura of dissolution thereby became the binding medium, coagulating drawing and building, ‘walls’ became porous interfaces between exterior and interior, drawing and architecture, reality and virtuality.

What was transduced from building to drawing was not the architectonic geometry of the room but a dynamic spatio-temporal quality of flow, an atmospheric space of affect. The erasure or dissolution of objects and content of architecture, leaving but a trace of their absence on the walls, refers back to their presence perhaps more intensely and affectively than would the contour of a departed object. Before the walls were deployed into picture planes, the room had taken on the virtual presence of its own drawing, which transformed my perception of its spatial relations. And the remaining traces continued to activate echoes of these qualitative relations after the event had perished, and the room had been deployed. The walls become self-referential-drawing that drew me into an uncanny impersonal ‘space’ of affect and imaginary perceptually and mnemonically related to the actual space, imbuing it with a renewed sense of meaning.

The occurrence of the dissolution of form into a relational-qualitative timbre was experientially amplified and made felt by the working conditions of the process itself. To prevent a ‘mess’ from the overflowing splatter of ink, the models were successively placed in a small white tent; its surfaces became a second membrane doubling the wall surfaces of the models. In the process of pulverisation, it operated as an echo chamber, expanding the models’ activated spaces and situating me within the space of the event. The ethereal plasticity of the architectural space traversed the body as the body inhabited its extended space and affected the image of projection onto the second membrane. The depth of space condensed into lived sensation.

Erasing the Barcelona Pavilion (a play on Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953) acts as a continuation of the previous drawing practices. Similarly, it explores the familiar space of Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion. Models of the project were constructed and basins of ink inserted into their interiors. The ink, propelled by the vortex, marked the absence of elements, columns, walls, furniture, and statues on perimeter surfaces. What emanated from the unfolded pictorial walls induced a spatial feeling that recalled and reconjugated the push and pull on the body experienced during a visit to the pavilion several years prior. The peripheral rhythmic patterns of light appearing and withdrawing, intermittently eclipsed by its objects, were sensuously echoed in the residual spaces that marked the walls. The emanation of form, the dissolution of its edges, evoked the lived movement-experience of the actual project, of matter appearing and fading in passing (Fig.3a). The vortical movement of air seemed to compress spatial depth into intensive matter and liberate its image in the fossilised traces of its passage. It evoked the timelessness of kinaesthetic memory and what survives experience in the mobilisation of place. In this sense, it was the topological nature of space-time, the arc of movement-experience and peripheral sensation which the walls seemed to expose.

Rather than producing the spatialized objective reality or the ordered regularity one might experience in viewing a perspective projection of the space, Erasing the Barcelona Pavilion conveys an experiential potential or surplus, a dynamic atmospheric timbre or tonality that supersedes any representation and/or its actual reality. Despite an effect of convergence, the centre of the vortex of projection visible on the dismantled floor plane in plan view (Fig.3b) is less akin to the vanishing point of perspectives that draws one into the infinity of vectorial space than to the silent eye of the hurricane that draws one into the cosmic expansion of resounding time.

In the end, what was inflected in this experimental and experiential process was not only the relation of drawing to building but also the very conditions of visuality: visible matter was rendered invisible and invisible space made visible and haptic. It is perhaps the sensuous synaesthetic capacity to move in-between the visible and invisible—to inhabit and activate their formative overlap—that enables space to come to life and engender an aesthetic-affective sense of place in the interval of drawing and building.

Notes

- For an extended version of this article, see Renee Charron, ‘Vor-textu(r)al Translations from Building to Drawing’, in BBDS – Black Book: Drawing and Sketching, Vol. 6, No 1 (2025): Drawing Territories, 8–15.

*

Renée Charron studied Architecture and Art Education at McGill University, and Fine Arts at Concordia University in Montreal, where she also completed an MA in Art Education / Interdisciplinary Studies and a PhD in Humanities Interdisciplinary Studies / Fine Arts. She is presently part-time faculty in Architecture and Design at the University of Montreal while pursuing research-creation work across architecture, drawing, dance and music.