Wang Shu: Drawing Uncommon Grounds

– Xin Jin

Despite the extensive literature on Chinese experimental architecture that emerged in the mid-1990s after the Cultural Revolution, architects’ reflections on and practices of representation remain under explored. Wang Shu (王澍), recipient of the 2012 Pritzker Prize, is a prominent figure in Chinese experimental architecture. Though widely acclaimed in the West for his innovative use of vernacular construction methods and recycled urban debris, Wang’s deeper intellectual engagement—particularly his explorations in architectural representation—is often overlooked due to limited translated works.

Wang earned his bachelor’s (1985) and master’s (1988) degrees in architecture from Southeast University in Nanjing, then completed a PhD in 2000 at Tongji University in Shanghai with his thesis ‘Fictionalising Cities’ (虚构城市). Based in Hangzhou, he and his professional partner, Lu Wenyu (陆文宇), co-founded Amateur Architecture Studio in 1997. Since 2007, he has served as Dean of the School of Architecture at the China Academy of Art. Wang’s intellectual development reflects influences from traditional Chinese culture as well as modern Western thought. He admires Aldo Rossi’s The Architecture of the City and draws heavily on structuralist and post-structuralist discourses, notably Roland Barthes’s theory of text and Claude Lévi-Strauss’s studies on mythical thinking. Wang’s doctoral thesis itself represents an experimental form of architectural writing characterised by textual appropriation and bricolage. The thesis challenges conventional notions of architectural authorship, critiques architectural theory’s role as metalanguage, and collapses the dualism between theory and practice.

Like his contemporary Yung Ho Chang (张永和), Wang critiques Renaissance perspective—not merely as a representational device but more fundamentally as an epistemological paradigm. His main reference point in this critique is traditional Chinese landscape painting and woodblock prints from the Song (AD 960–1279) and Ming (AD 1368–1644) dynasties. For Wang, these traditional works present an alternative mode of representation, characterised by non-mimetic representation of depth, immersive spectatorship, and fragmentary composition. Unlike the Albertian perspective window, traditional Chinese landscape painting, as emphasised by Wang, invites viewers to enter and inhabit the depicted space.

These pictorial traits have notably shaped Wang’s architectural drawings, particularly in his evolving use of parallel projections, including axonometry and oblique views. In his student and early project drawings, he favoured parallel projection for its abstraction and often depicted architecture as self-sufficient objects. During this early phase, his oblique drawings typically stemmed from orthogonal plans, which reduced the architectural ground to planar geometries. However, in later works, Wang shifted to meticulously depicting the concrete topographical features of the architectural ground and landscape. With this shift, Wang’s drawings invite viewers to wander through the depicted space rather than objectify architecture as an autonomous entity. Instead of using parallel projection to coordinate pictorial space, he employs it as a fragmentary signifier of depth. By intensifying and prolonging viewer engagement, he reintroduces time into his drawings. These developments go beyond stylistic considerations and reflect Wang’s broader ethos of reconnecting architecture to the concrete lifeworld. The following excerpt, focusing on Wang’s design sketches for the Tengtou Pavilion (滕头案例馆, 2010), highlights a critical moment in these transitions.

Tengtou Pavilion: section-oblique and concrete ground

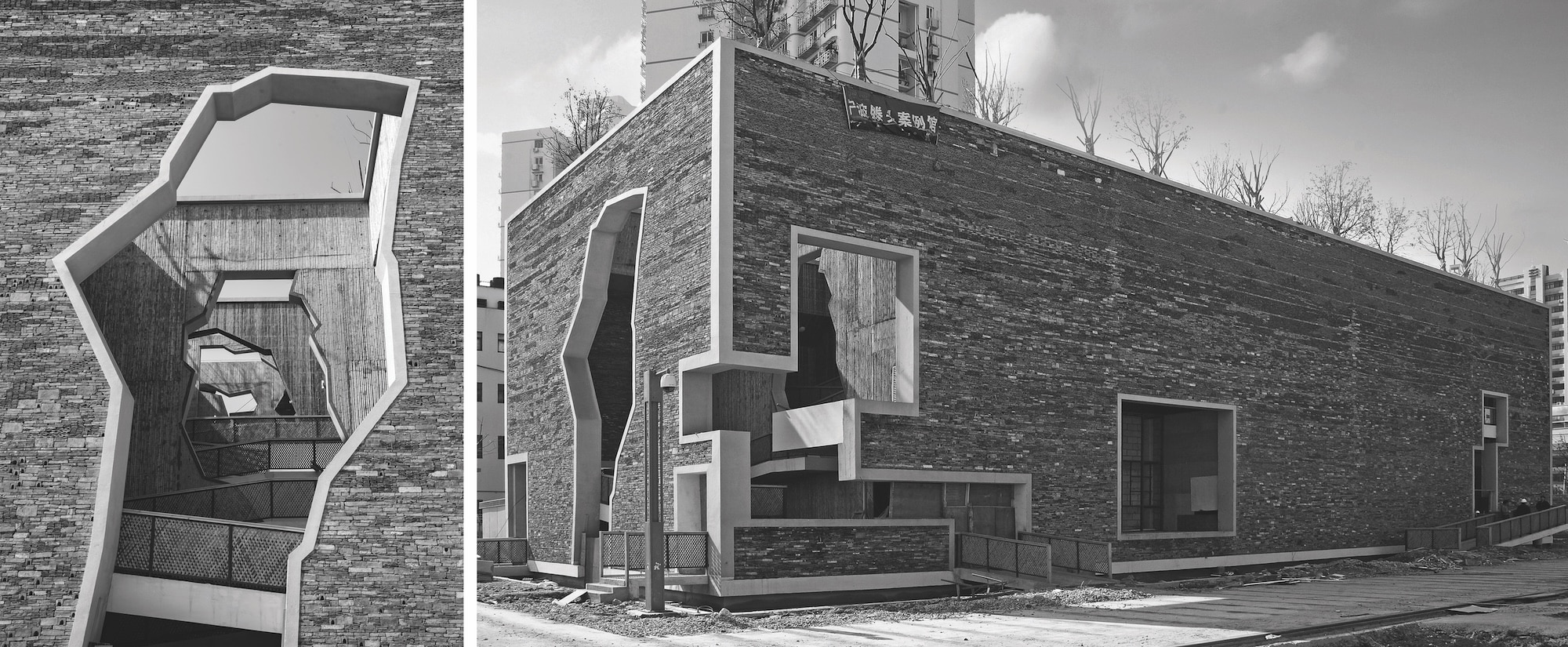

In 2009, the Amateur Architecture Studio, which was co-founded by Wang and his professional partner, Lu Wenyu, was commissioned to design the Tengtou Pavilion, Ningbo City’s exhibition house, for the 2010 Shanghai Expo. In his designs for the project, Wang continued to intervene in the perception of spatial depth through the architectural layering of walls. On the restricted plot (50 m long and 15 m wide), the architects aimed to create an effect of ‘ever-deeper space’ by inviting visitors to circumnavigate a series of densely aligned, self-similar building layers (Fig.1).[1] Despite his repetition of the idea of spatial enlargement through layering, Wang’s oblique drawings for the Tengtou Pavilion exhibit different, even contrasting, features from his Chen Mo Art Studio (陈默工作室, Haiyan, 1998) drawings. Wang’s Tengtou Pavilion drawings went from plan-based oblique drawings to sectional plane-based oblique drawings. From this shift in drawing methods arose further changes in Wang’s design approaches. In the Tengtou Pavilion oblique drawings, Wang avoids reducing the building’s horizontal depth to orthogonal geometrics; rather, he depicts the building’s floors as sensory topographies that could stimulate viewers’ imaginative inhabitations.

Entering the painting

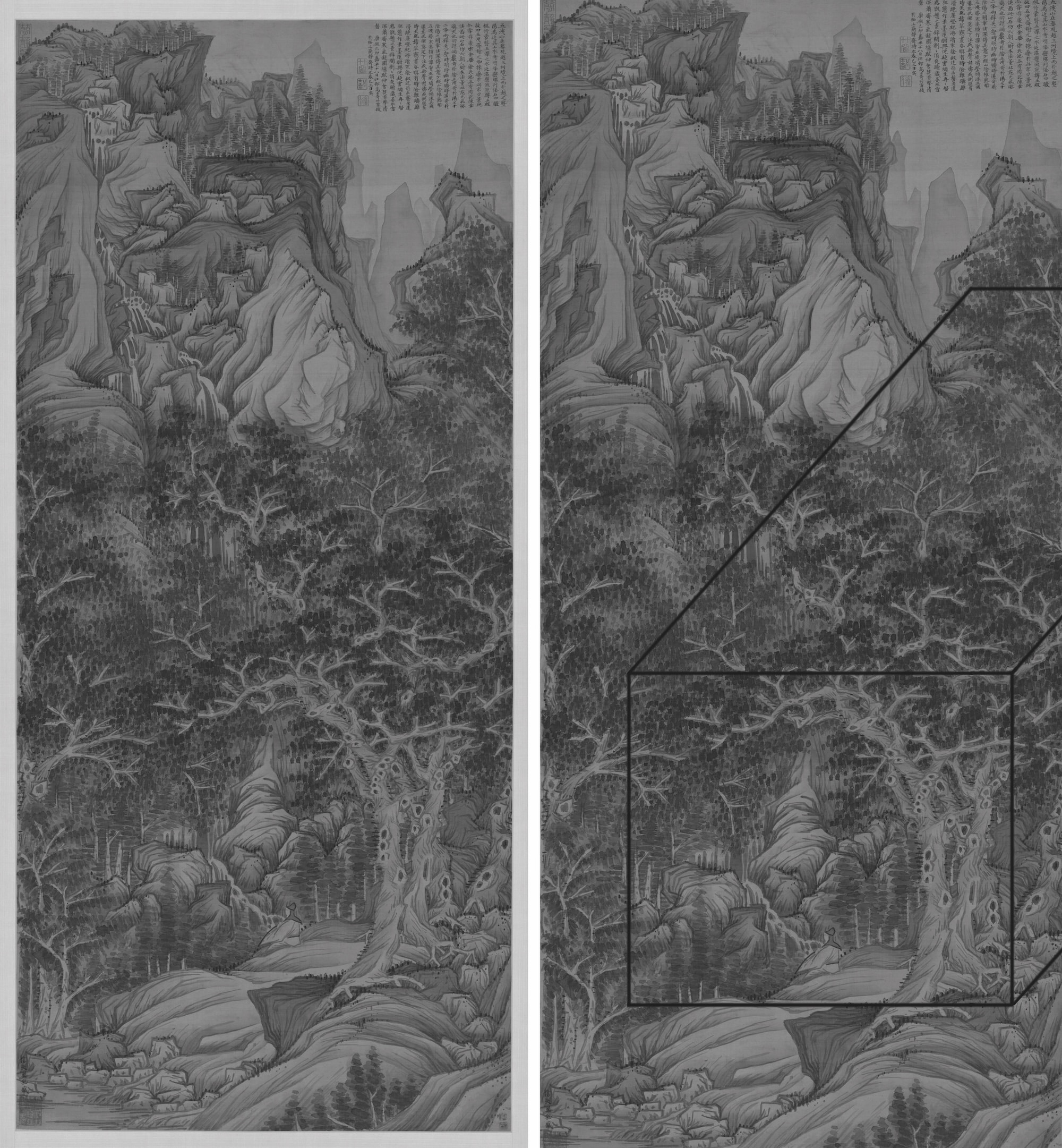

Immersive spectatorship played a prominent role in the Tengtou Pavilion’s design. In fact, Wang’s proposal was a product of his own experience of imaginarily walking into the Ming Dynasty (AD 1368–1644) painter Chen Hongshou’s hanging scroll The Mountain of Five Cataracts (五泄山图, 118 cm x 53 cm, 陈洪绶, AD 1599–1652) (Fig.2). In his drawing notes, Wang referred specifically to several elements of Chen’s painting:

A path twisted its way deep into a hollow space formed by trees, which also implied the depth of thoughts. […] That hollow space impressed me, half natural and half artificial. They shaped a shading space on a thin, two-dimensional sheet of paper.[2]

Wang’s notes were accompanied by a visual diagram where a cuboid frame, drawn in oblique, is overlaid onto Chen’s painting. This cuboid serves a dual purpose: it visually represents the architectural volume of the envisioned pavilion and, simultaneously, extracts key elements from Chen’s artwork.

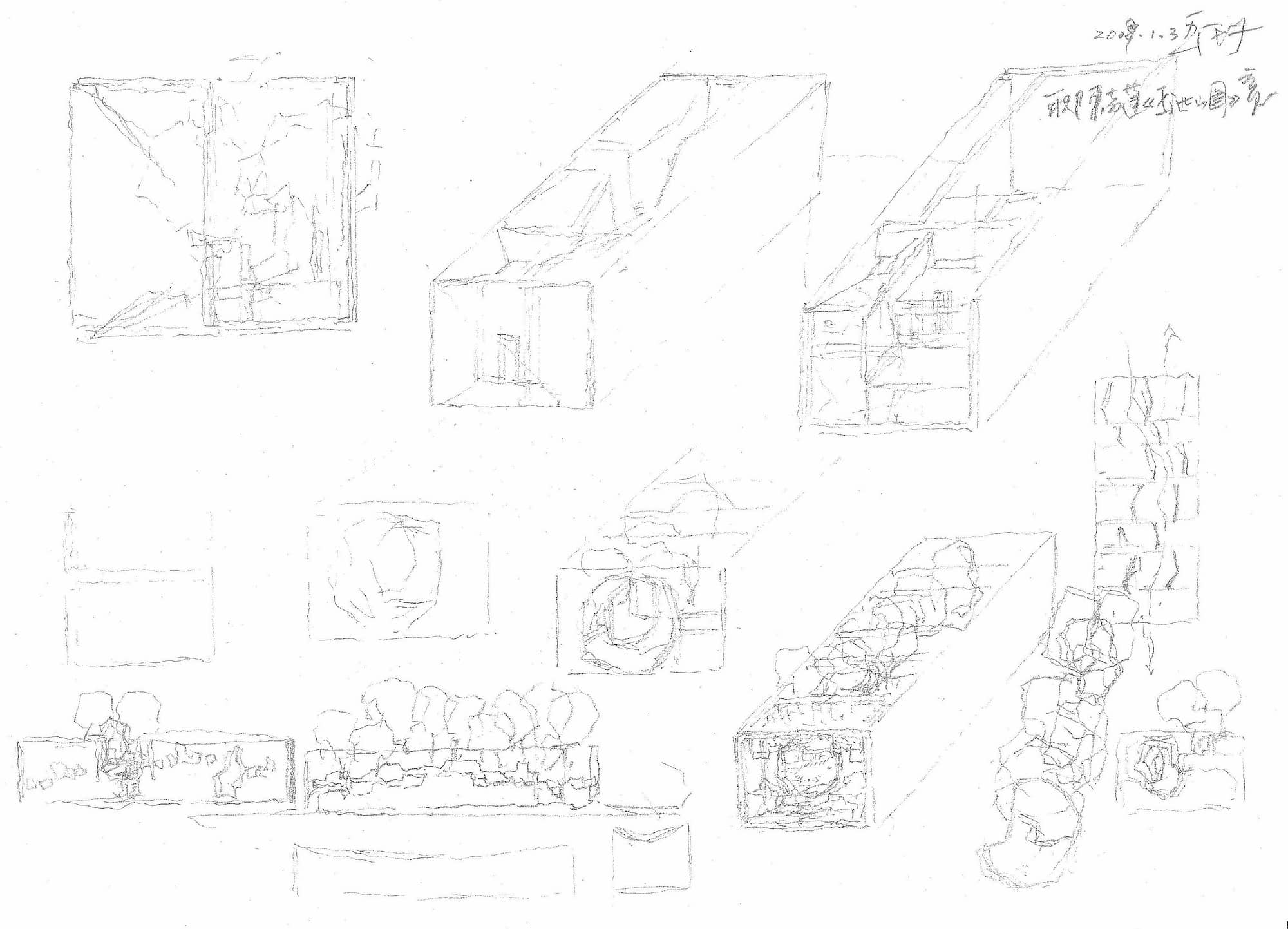

In his preliminary design sketches for the Tengtou Pavilion, Wang transformed the extracted elements from Chen’s painting into architectural components (Fig.3). The ‘hollow space’, or the holes created by trees, became the pavilion’s layered wall openings. The openings’ contours were depicted in ‘a more geometrised vocabulary’, which could be found in Chen’s depictions of the background hills.[3] In his notes, Wang also emphasised the parallel between his process of drawing and designing the Tengtou Pavilion and his journey of imaginarily ‘walk[ing] into it [Chen’s painting]’.[4] Wang wrote:

I felt as if the building had already existed [in Chen’s painting]. What I was doing was guessing and memorising around it [the envisioned building] […] with the hand-drawn depiction on paper, my memory and guessing became more and more accurate.[5]

Several aspects relating to Wang’s mental inhabitation of Chen’s painting, which were only vaguely hinted at in his notes, warrant further elaboration. First, because the architectural volume represented in oblique is superimposed onto Chen’s painting, Wang’s wandering inside Chen’s mountainous scape concurs with his imaginary walk into the envisioned pavilion (Fig.2). Second, Wang’s mental meandering necessarily requires fictionalising the horizontal floor of the proposed pavilion. Excepting the lower section, Chen’s painting notably abstained from portraying the ground. Inside the tree hole, the scene provided limited visual cues for navigating deeper into the mountain. Essentially, Wang has to grapple with the challenge of supplementing the absent yet implied horizontal depth in Chen’s painting by illustrating the retreating floor of the envisioned pavilion.

Drawing uncommon grounds

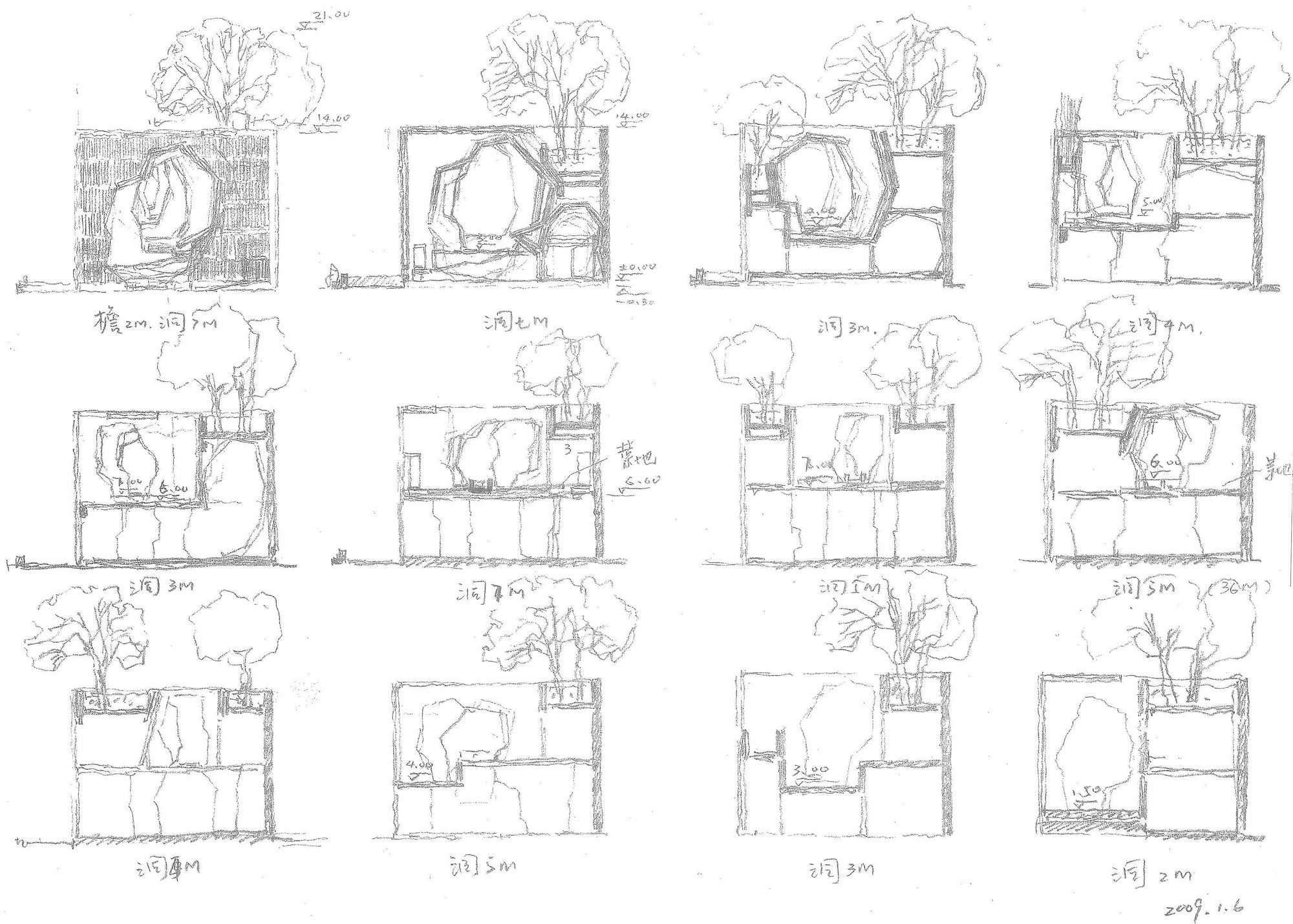

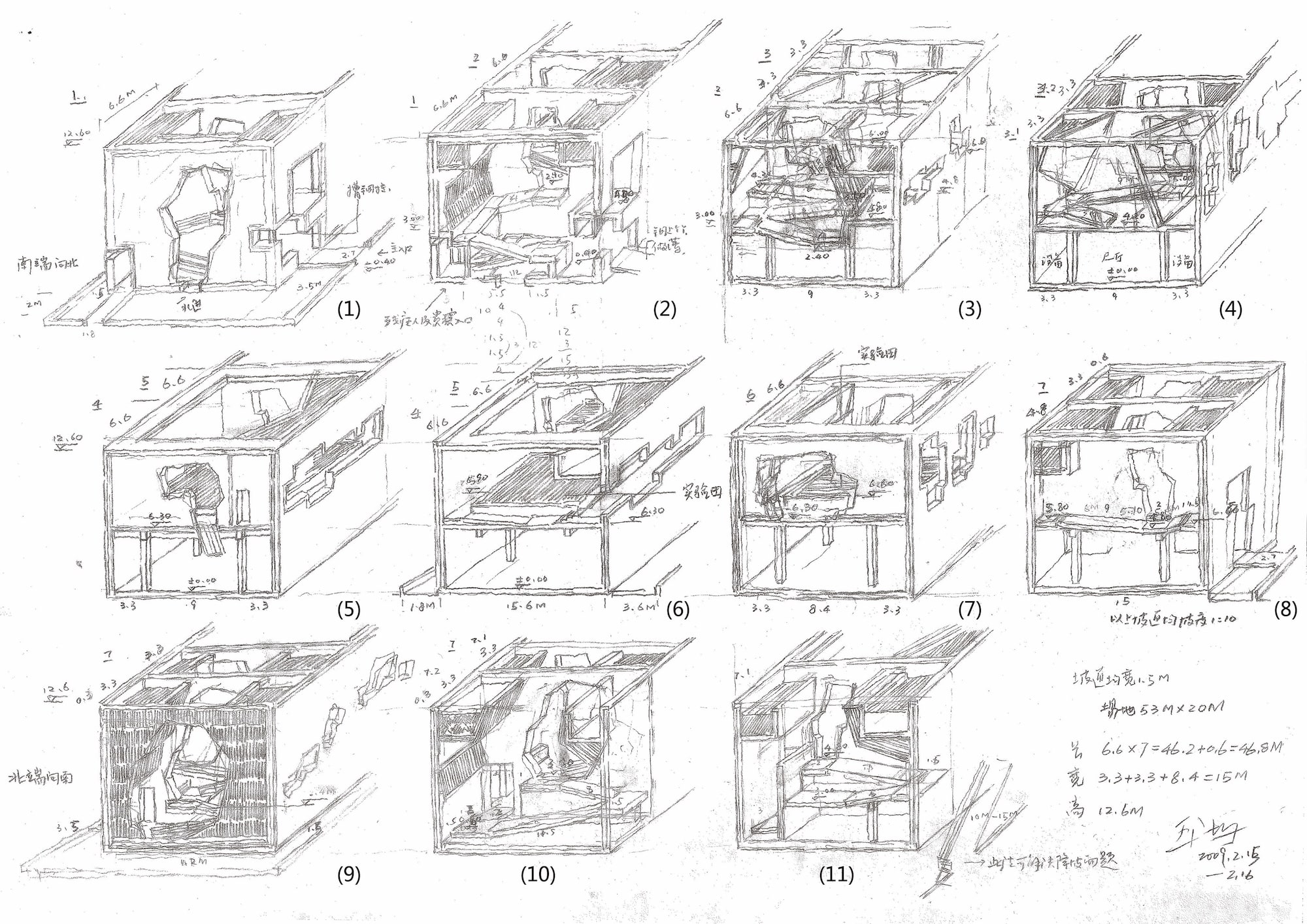

Based on a close reading of Wang’s drawings, this essay suggests that his approach encompasses two primary operations. First, he chose to delineate the horizontal space extension of the Tengtou Pavilion incrementally, section by section. This approach contrasts with his treatment for the design of the Chen Mo Art Studio, where he coordinates the horizontal extension within an overarching planar geometry. Wang has confirmed that, for the Tengtou Pavilion, he ‘decided to start drawing from sections’.[6] He holds that the sequential order of drawing plan, elevation, and section reflects one’s way of engaging with architecture. In this case, the pavilion’s plan came later as an a posteriori product for practical uses.[7] Wang drew 12 sectional drawings, each of which represented an architectural variant of Chen’s tree hole (Fig.4). Based on the 12 sections, Wang proceeded to draw 11 obliques to further study the intermediate floors between the sectional planes (Fig.5).

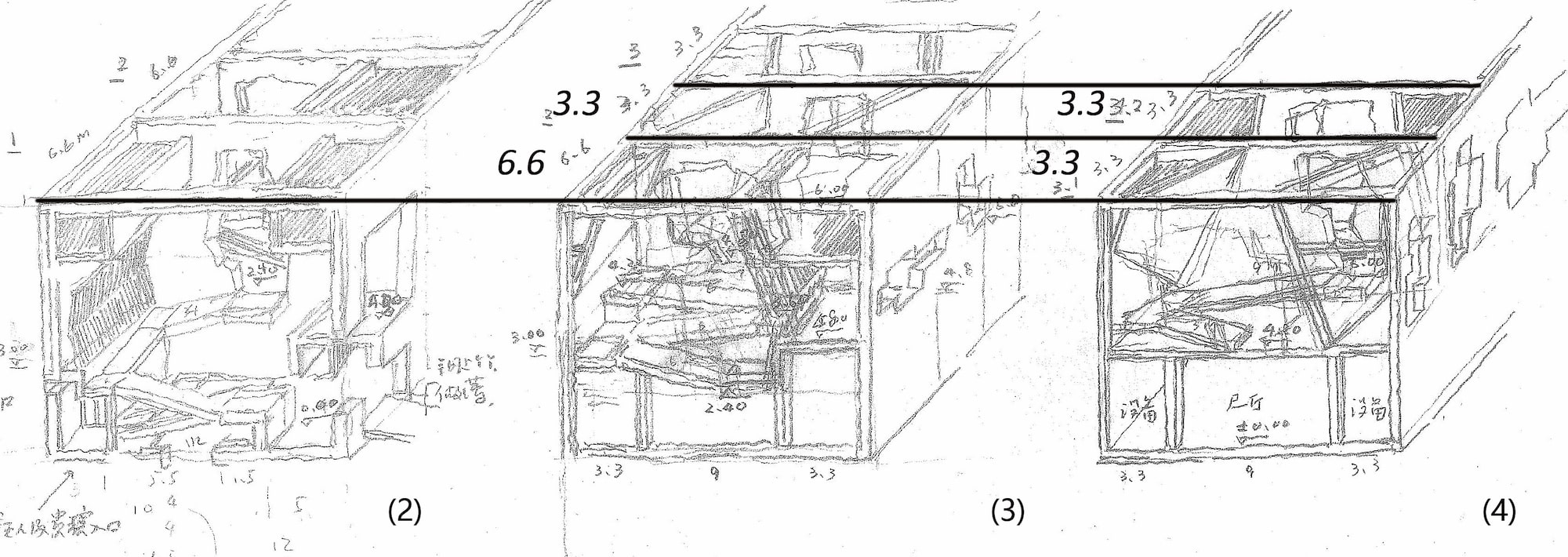

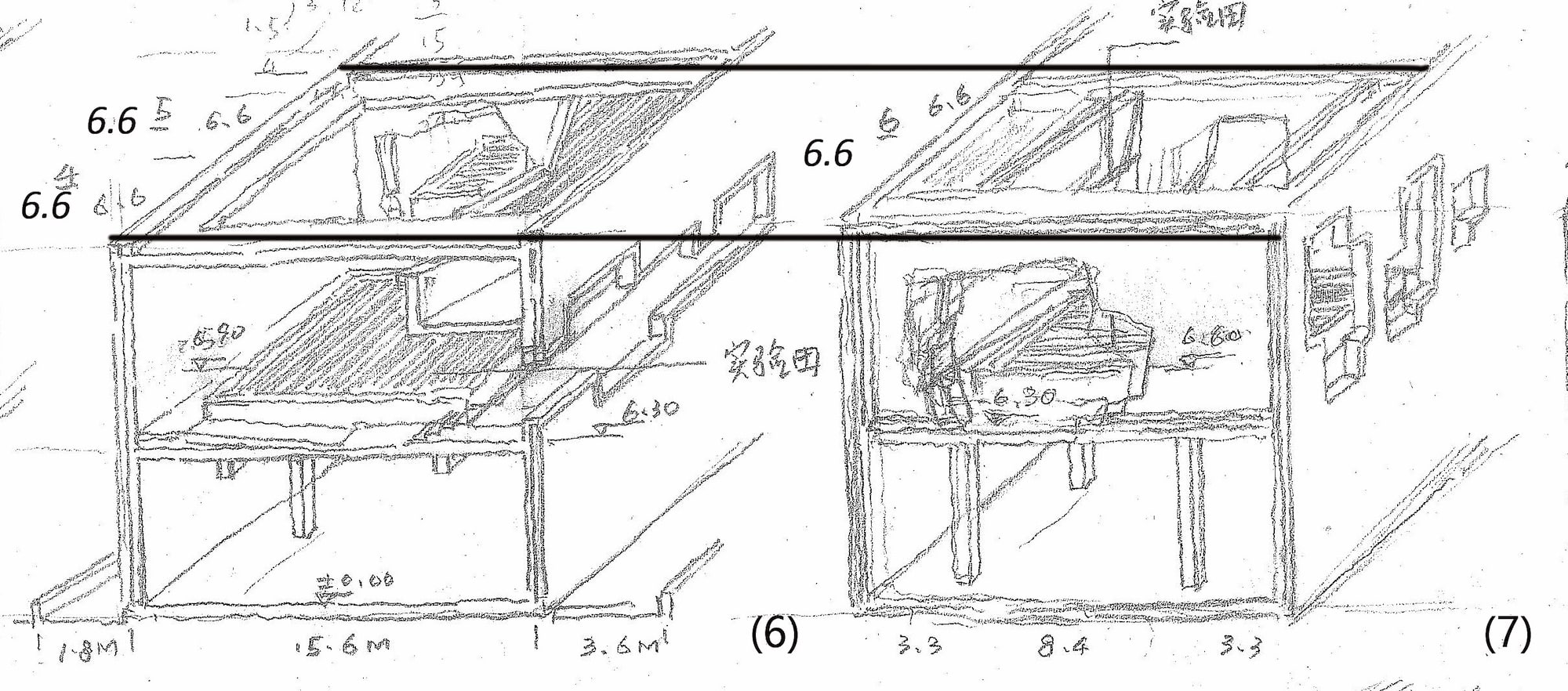

In addition, the diagonal extrusions in Wang’s 11 section oblique drawings are not drawn to a consistent scale (Fig.5). For example, in Oblique 3, the two different lengths (3.3 m and 6.6 m) are drawn as almost equal lengths. This visual equivalence of different lengths also applies when one compares Obliques 2, 3, and 4 (Fig.6). Remarkably, the 6.6-m length shown in Oblique 7 is almost identical to the 13.2-m length shown in Oblique 6 (Fig.7). Notwithstanding, all the frontal sections are drawn to the same scale. These instances indicate that, among Wang’s 11 section oblique drawings, there is no totalising axis governing the representations of spatial recessions. Conversely, Wang combines inconsistent oblique projection fragments resulting from changing projection angles to formulate ostensibly linear yet discontinuous diagonal recessions. In the simplest terms, Wang’s oblique drawings juxtapose multiple incommensurable oblique projections to represent depth.

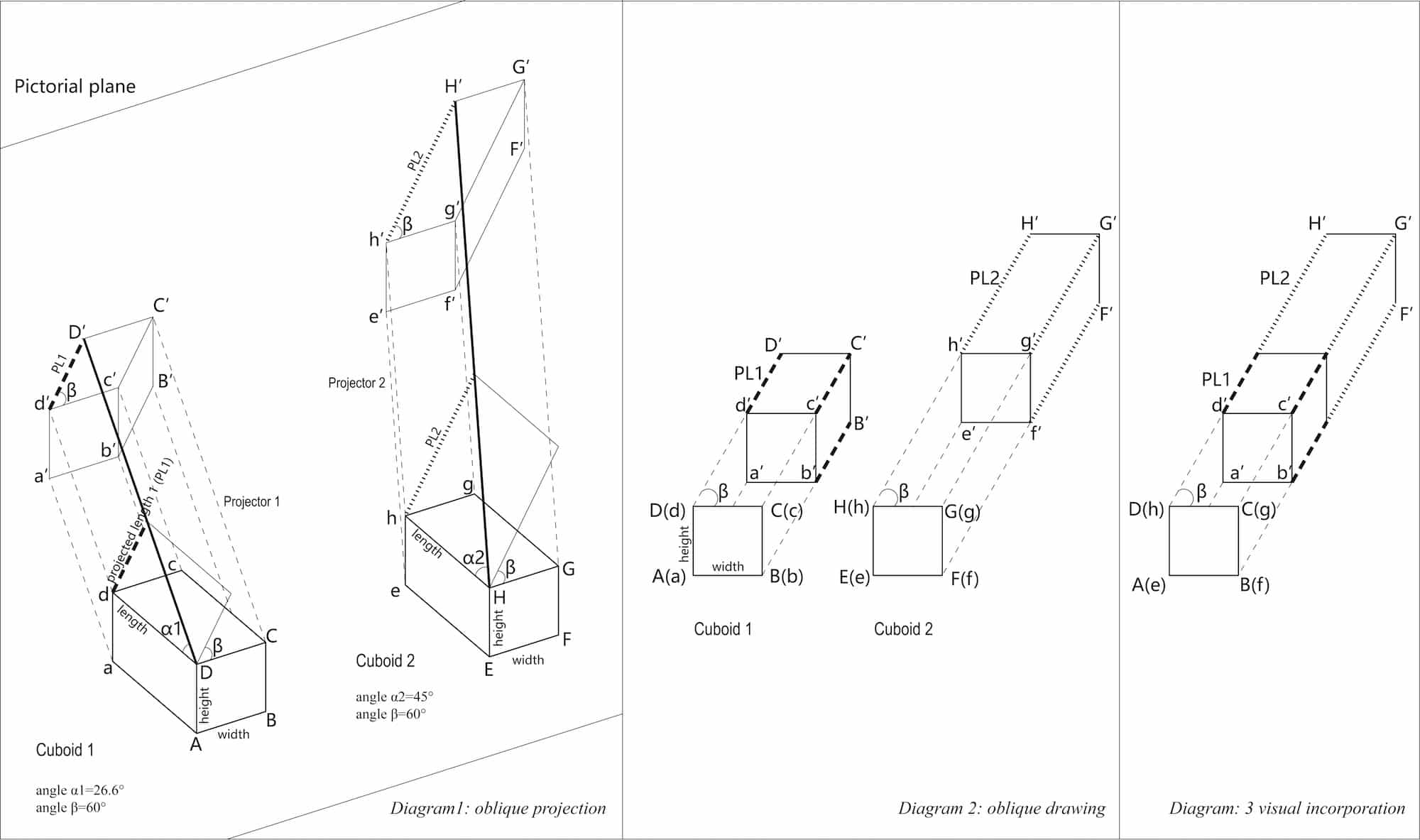

In figure 8, this essay provides additional details that further expound on the aforementioned conclusion. The three diagrams in this figure demonstrate Wang’s method to combine multiple incommensurable oblique projections in his drawings. Diagram 1 shows that the equal lengths dD and hH of two congruent cuboids are projected onto a pictorial plane with different sets of projectors. The two sets of projectors share the same angle β (60°), which determines the extrusion angle of the projected length (PL) of the cuboids, but do not have the same angle α (α1 = 26.6°; α2 = 45°), which dictates the metric measurements of the PLs. However, during the actual process of drawing the cuboids in oblique on paper (Diagram 2), which corresponds to the above mentioned systematic projection procedures, the overlap of the projector and the PL obscures angle α’s alteration. Consequently, the incommensurable PL1 and PL2 can be incorporated into a single visually continuous diagonal axis (Diagram 3).

By juxtaposing multiple incommensurable oblique projections in figure 5, Wang employed the oblique method as a quasi-collage device. Each oblique fragment still conveys illusory spatial recession, but he went beyond this mimetic representation by creating spatial voids between the incommensurable fragments. The spatial voids defy mimetic representation since they are not modelled on spatial recession but are implied by discontinuities and inconsistencies in the representational images.

Wang’s use of the collage oblique is instrumental in achieving the effect of ‘ever-deeper space’, which was a core concept in the Tengtou Pavilion’s design. His drawings vividly depict the architectural grounds as tangible topological features, enticing viewers to traverse the episodically laid out architectural scenes. With meticulous detail, he delineates subtle changes in the elevation levels, the semi-interior corridors, the gradually ascending ramps, the short bridges, and the planting trays. Simultaneously, the voids prevent the depicted floors from merging into a single homogeneous ground plane; rather, the voids suggest the existence of more spaces beyond the confines of projection geometry. Wang’s Tengtou Pavilion drawings originated from his imagination of the implied depth in The Mountain of Five Cataracts. In turn, his collage oblique continues to foster such imagination in viewers’ minds.

Drawing Matter would like to thank Cambridge University Press for allowing us to republish an excerpt from the article: Jin Xin. Beyond perspectival vision: case studies of Wang Shu’s landscape painting-inspired parallel projection drawings. Architectural Research Quarterly. 2023; 27(4): 288–299. © The Author(s), 2024. Published by Cambridge University Press.

Notes

- Shu Wang, Imagining the House (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2013), under ‘A Picturesque House’. (This is the original translation)

- Ibid. (This is the original translation)

- Shu Wang, ‘The Field of Vision on Section’ [sic] (‘剖面的视野’), Time+Architecture (时代建筑), 2 (2010), 80–88 (85).

- Wang, Imagining the House, under ‘A Picturesque House’, 4.3.

- Wang, Imagining the House, under ‘A Picturesque House’, 4.1, 4.2.

- Wang, ‘The Field of Vision on Section’, 86.

- Ibid.

Xin Jin is a faculty member in the Department of Architecture and Urban Planning at Chongqing University, China. His research focuses on the history and theory of experimental architectural representation, with a current project examining case studies of representations by Chinese experimental architects. He has published papers on this topic in prestigious international and Chinese journals, including The Journal of Architecture, Architectural Research Quarterly, Architectural Journal [建筑学报], and The Architect [建筑师].

*

Further reading…

The Museum of Modern Art’s online catalogue features 18 of Wang’s design sketches, including those for the Xiangshan Campus of the China Academy of Art, the Ningbo History Museum, and the Fuyang Cultural Complex. Wang Shu: Imagining the House (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2013) presents a selection of his hand-drawn iterations across multiple projects from 2003 to 2013.

For insights into the relationship between Wang’s interpretation of traditional Chinese landscape painting, his design drawings, and architectural practice, consider the following sources:

Shu Wang, Leçon inaugurale de l’École de Chaillot: Wang Shu, online video recording, YouTube, 14 June 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HT9MmjiTDwc&t=1296s> [accessed 11 April 2025].

Shu Wang, ‘The Narrative of the Mountain’, Log, 45 (2019), 10–25

Shu Wang, ‘Build a World to Resemble Nature’, trans. by Jiinyi Hwang, in Architecture Studies 02: Topography and Mental Space, ed. by Mark Cousins and Wei Che (Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press, 2012), 173–212.