What’s a Bludder Sketch?

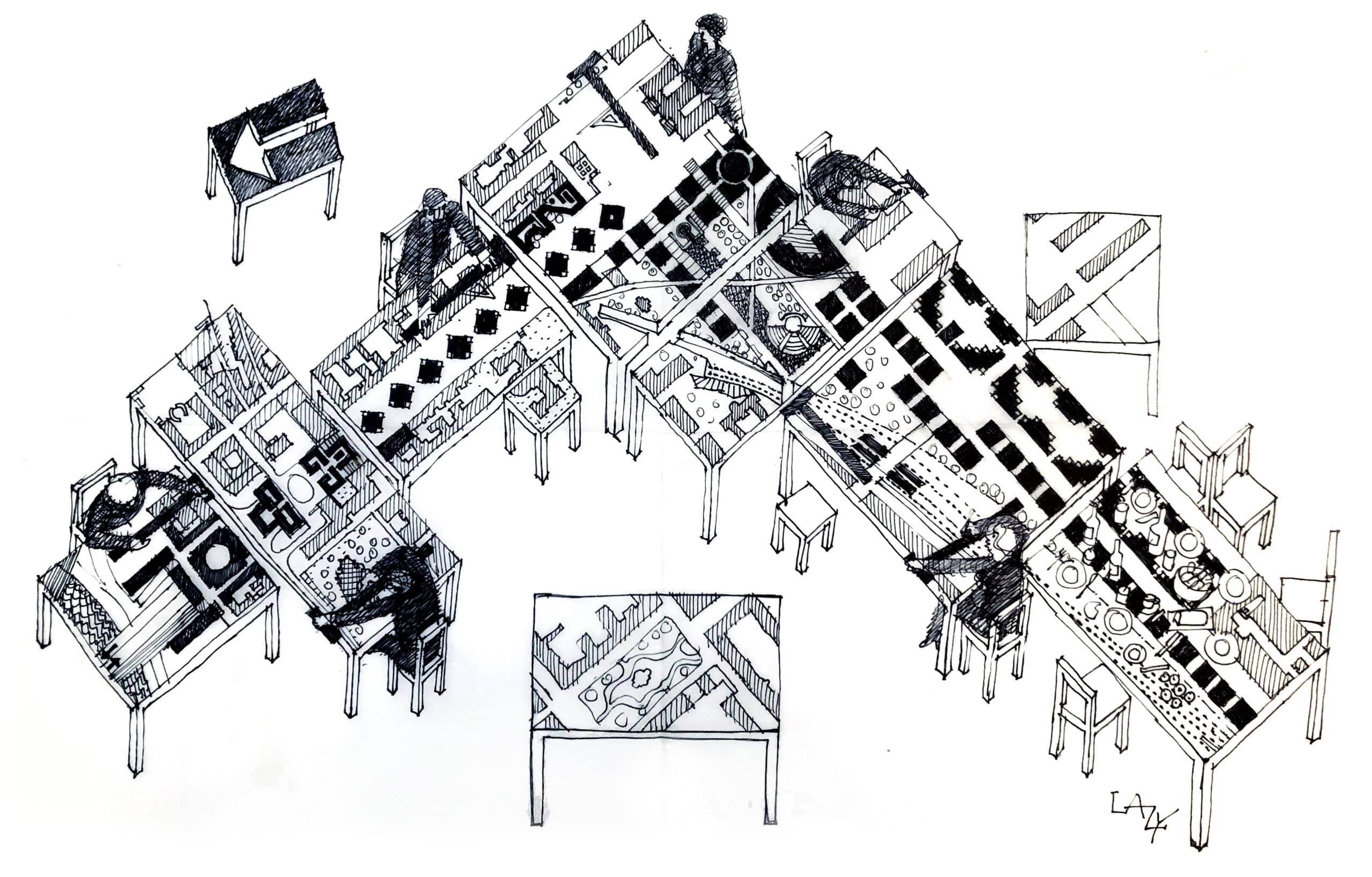

As a timid foreigner in the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design, shuffling through hundreds of important-looking drawings, I stumbled across a funny little sketch in whose lines I found some humanity. It was made by Bengt Lindroos in 1981 and is an imagined view of his office with the members of his studio drawing a masterplan for inner-city Södermalm in Stockholm.

Like those famous sketches by Álvaro Siza, the drawing reveals the designers amidst the design. It has a reflective, inward-looking perspective, and presents the world of architects in a human way while showing the fruits of their labour. It shows how we change the world through occasions as small as a conversation over wine. It presents the architect as a person and city planning as a light-hearted affair. The plates, cups, and wine bottles left behind from a dinner tell of a world that is not so serious. It is energetic and full of life.

Drawing the drawing process, Lindroos brings us into the imagined axonometric space of this piece and, in doing so, offers further insight into the imaginary space of the 2D masterplan. A step back from the drawing board, his view of the studio work also becomes an overhead view of the city. In the masterplan he draws how the city could be, in the sketch he draws how the studio could be—new ways to live and work. It describes a reality that we can’t see, in the wonderful way that drawings do. The buildings drawn here were never built, and the strange tables never existed. The sketch is a layered fictional tale told in imaginary past and conditional future tense.

The sketch was made for the comedy magazine Blandaren, of which Lindroos was a regular contributor under the pseudonym LAZY. In a 2013 edition of Osqledaren, Hugi Ásgeirsson described the great ritual involved in making Blandaren: the members gather twice annually for a feast with copious amounts of food and wine, while a microphone hangs over the table connected to a tape recorder and everything that is said during the evening is recorded. In words and drawings, layer upon layer of associations builds upon each other until the conversation becomes completely incomprehensible. Later, the evening’s conversations are transcribed word for word, and the scribbled illustrations are gathered together. The result is what Blandarens call a ‘bludder’: a stream of conscious creative flow with no need to make sense. The sketch from Lindroos is an example of the potential reflective qualities of this playful bludder. There is a charm to it. I can imagine Lindroos sketching with a smirk. It has a scribbly off-hand character, wit, and joy. The fun of drawing is present at both scales.

In the world of this sketch, the line that describes the proposal also describes the table, the dinner, and the architects themselves. That what exists is lightly hatched, the architect is darkly hatched and the proposed is coloured in black. The fantastical tables scattered throughout the drawing are constructed to fit the context, then separate to leave space for sliding T-squares. Each table is a custom size and shape. In one corner, railway tracks slice up a worktop. A separate table has been constructed to include the small park at Mariatorget, added to show the east side of a church (which must have been an afterthought). Another was specially constructed as a north-symbol—though I would question its stability…

In Lindroos’ signature style, the presence of the square and circle are primary. The simple square chairs and tables, like the plan, are without material, depth or detail. They are furniture symbols in this story, just as the masterplan is a collection of representations, not superimposing too much reality. Near the centre of the drawing we see one stool and a T-square laying in wait. Perhaps it was Bengt’s own, from which he had stepped up to take stock, or perhaps it invites a sense of participation.

The immense archive that Lindroos has left behind in Arkdes is a testament to his fervent drawing habits. Thousands of sketches exist for this competition alone, and this little jest sits among them. Without its addition they appear cold, serious, and technical. With it, you see a body of human joy and effort. In recent years we have begun to see that history is a malleable resource, morphing new realities when seen through different perspectives. In fiction we can take on nomadic perspectives. Sketching and writing exist in transitory worlds.

The sketch also invites the question: if we were to create another axonometric imagined world of our studios today, what might they show us?

Declan Quirke is an Irish architecture student. He is currently completing a Masters degree at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

This text was submitted to the Student Archive category of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2021.