Where in the World are We? Melbourne Venice Studios 2022

Remote teaching as a pandemic consequence has already been a theme for Drawing Matter, in the January 2022 Melbourne University Venice Workshop it reached an almost surreal zenith.

Remoteness is fundamental to Australia, whether the extreme separations of the outback or a pre-digital geographic estrangement from global cultural discourses. At that time, I knew avid Australian magazine readers (Domus, etc.) who, to compensate for their endemic isolation, knew more about the goings on at the British Museum or in Milan than any well-informed European. Now, with digital tools, the famous Australian Cultural Cringe is threatened by a radical connectivity.

As Biennale junkies, the Architectural Faculty of Melbourne University are in the habit of organising annual Venice Workshops. Under covid travel restrictions this mutated into virtual trips to Venice. Having led one of these from my office in Germany, I was recently promoted to front one of nineteen workshop groups lead by international offices: Snøhetta, UN Studio, Sauerbruch+Hutton, Monadnock, Baukuh, Dogma, Zaha Hadid Architects, Sean Godsell, MVRDV, Moreau Kusunoki, Young + Ayata, 2059+, Lütjens Padmanabhan, Dorte Mandrup, MOS, MAD Architects, Armature Globale, Salottobuono, BOLLES+WILSON.

Each group had a maximum of five students (many had applied internationally) to work together on a group project. Having opted to teach 1 to 1 (and not like most studios to delegate to office assistants) I selected a small group of three students. The one Australian, a surfer with digital muscle, came down on day-one with covid. The remaining two were Russian (pre-Ukraine invasion): Sergey in Moscow and Anastasia on holiday with her family in Bermuda, Zooming each day for one hour with me in Münster, Germany.

SANT’ELENA

Sites were issued, we and three other groups landed in Sant’Elena at the extreme eastern edge of Venice. (We felt like Malaparte exiled by Mussolini to Lipari, taking his Mama with him and returning to Capri with the idea of an extremely sexy staircase). Sant’Elena is the home of the Venice football team and our prescribed site now a boatyard for vaporetto construction and maintenance.

We noticed that Sant’Elena was also the grey zone immediately behind the Biennale Gardens (the epicentre of architect’s Venice fetishism). The Eurocentric National Pavilion ontology of the existing Biennale layout seemed to be a possible theme for this fringe location to question.

Concurrently, a slow storm was brewing on the horizon of First World Museums concerning the return of artefacts plundered from African countries under colonialism and now held in collections in London, Berlin, Brussels, Paris, and North America. Although supported by UNESCO, African applications for the return of their cultural heritage have been systematically ignored for the last 50 years. The new Humboldt Forum (reconstructed Schloss) in Berlin had even planned an opening Treasures of Africa exhibition until whistleblower art historian Bénédicte Savoy published Africa’s Struggle for its Art (in German – C.H.Beck publishers).

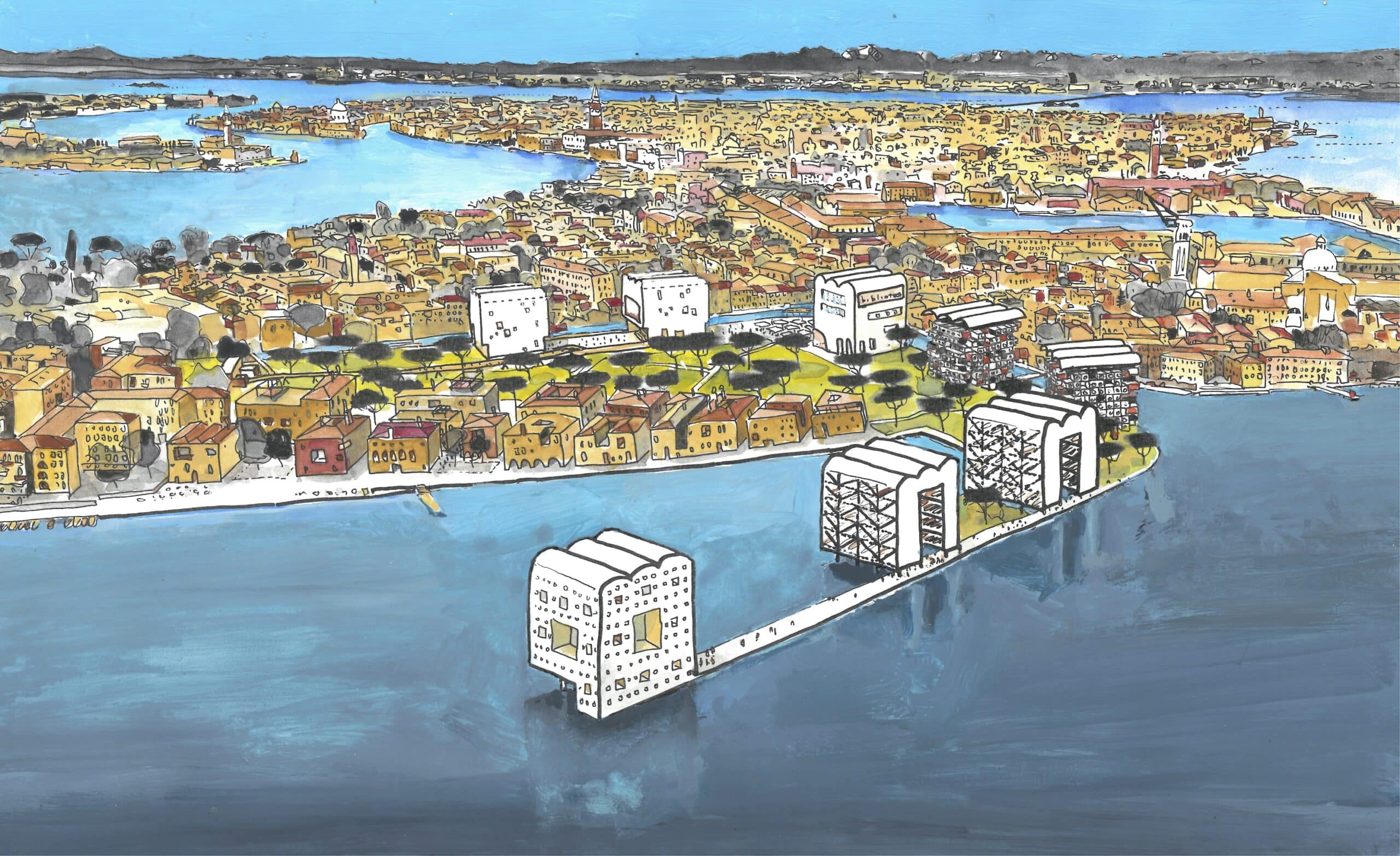

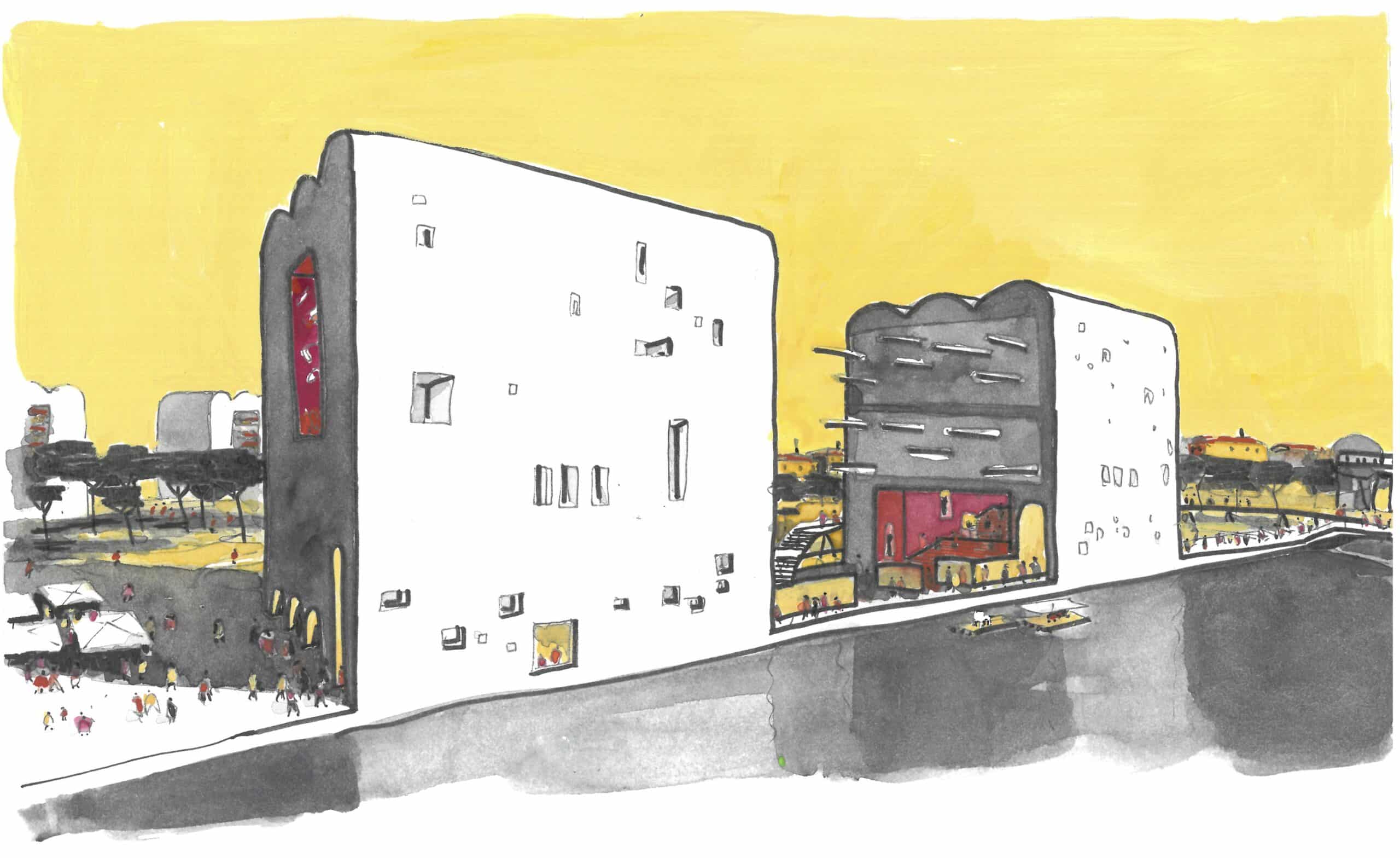

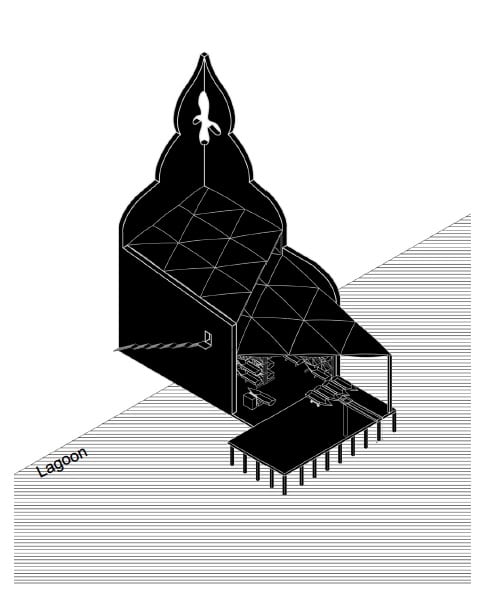

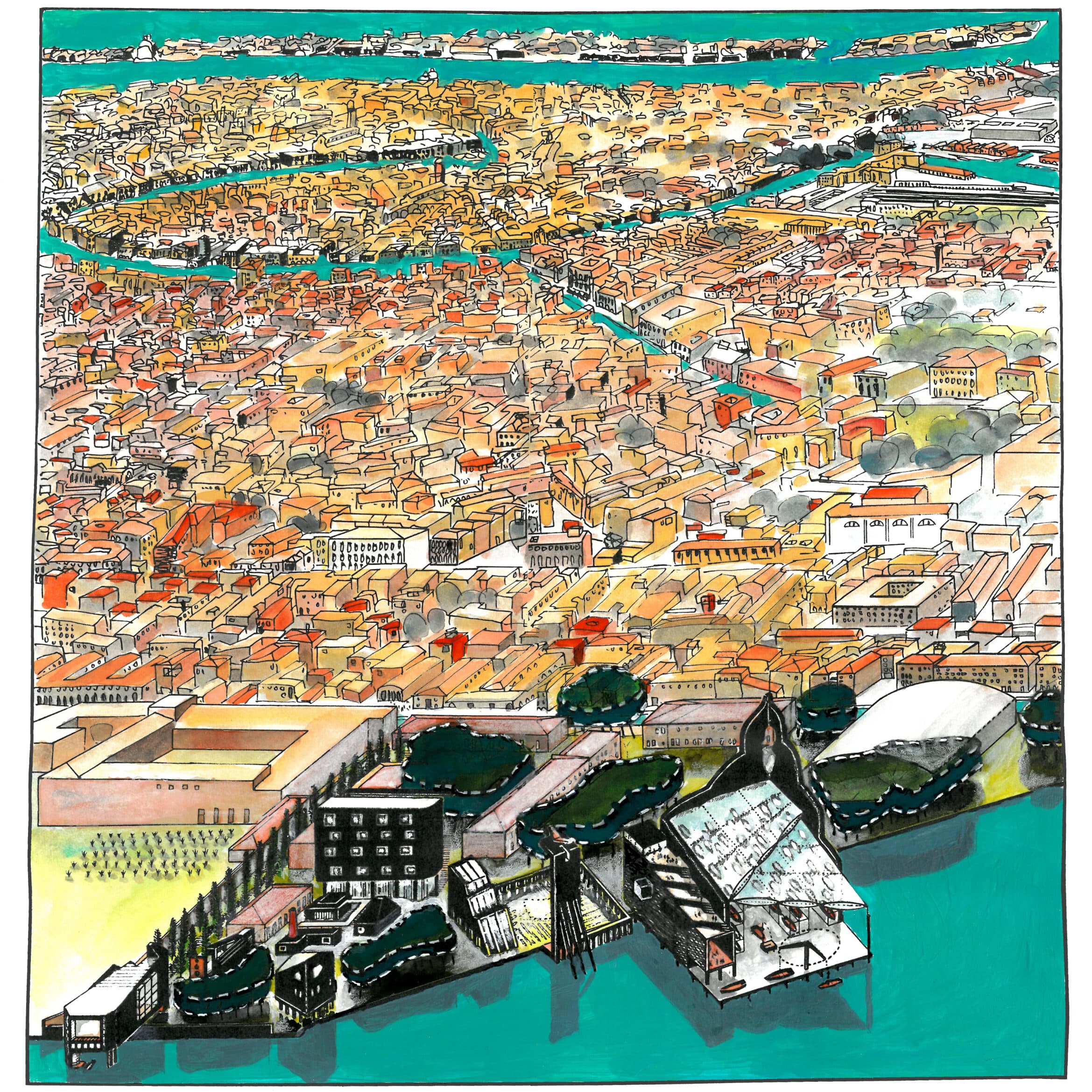

As there are no African pavilions in the Biennale Gardens, a House of the Global South anchored our studio’s Sant’Elena masterplan. Here artefacts on their way back to their African country of origin (e.g. Benin Bronzes to Nigeria) could be displayed. This House of the Global South is accessed by a Biennale bridge that leads fortuitously out from the Giardini through the back door of Hoffmann’s 1934 Austrian pavilion.

The incentive for speculative architecture to fuel debate on cultural imbalances was extended to a proposed second pavilion, this time for Stateless Artists, a considerable group that is invisible in their countries of origin and in need of Biennale recognition.

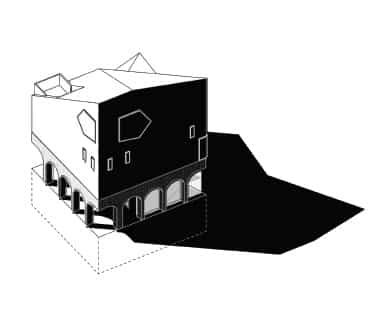

The masterplan that emerged from our limited team of two was fast-tracked over 8 days by co-opting the locations of the 30 x 30m boat-building sheds already on the site (a time saving expedient engaging an inherited plan DNA) and projecting them up to larger cubic volumes with vaulted roofs – a singularly Venetian ‘sheds on steroids’ typology. Following a function follows form causality sequence, further sheds landed, housing a library, 2 small-boat mechanical-parking-sheds (to solve the ‘cluttered-canal’ parking problem), two student housing sheds (Kurakowa Capsules), and a rescue archive for ‘Venetian high-water-threatened-artefacts’. Two new vaporetto stations, a park, and dense generic housing completed the masterplan ensemble.

GLOBAL JURY

The ‘Where in the World’ question finds extreme polarity in agreeing what time to chat. Taking Venice as the topographic datum and Melbourne as the organisational node for the 19 workshops led to studio juries at 9am European time and 7pm Melbourne time – a small window of communication. It being midsummer and holiday season in Australia led to live evening presentations in an open-air pavilion near the Melbourne Botanical Gardens. This was 4pm China, 3am New York and early morning in Moscow.

All 19 juries ran on Monday 19 and Tuesday 20 January 2022, a logistical masterwork from programme initiator Scott Woods who also compèred live in the subtropical Australian twilight.

For my Sant’Elena jury, aware that we were speculating at the edge of our cultural competence, I invited an African juror, the seasoned Biennale exhibitor Patti Anahory based in Cape Verdi (yet another time zone and south of the equator). An African voice was necessary for our ‘artefact-return’ scenario, and Patti quite rightly pointed out that we were not talking about frozen and mute museum objects; the colonial booty of icons and fetishes would have been animate components of ritual and daily life in pre-colonised nations. Might the returned artefacts now initiate a revalidation of local cultural awareness counter to that of a global neoliberal hegemony?

The planning scenario resulting from this global discourse was in conclusion summarised in my Director’s-Cut-Aerial-Perspective [above], with a familiar Venice unfolding in the background, and in the House of the Global South section.

ARE WE NOW IN VENICE?

In July 2022 (Australian winter, European summer) the next Melbourne University Venice Workshop was post-pandemic possible, and participants and students met in a Palazzo on the Grand Canal. The canal itself was attacked by the Zaha Hadid studio’s project, which provocatively projected a parametric-noodle vaporetto station right next to the Rialto Bridge… oops.

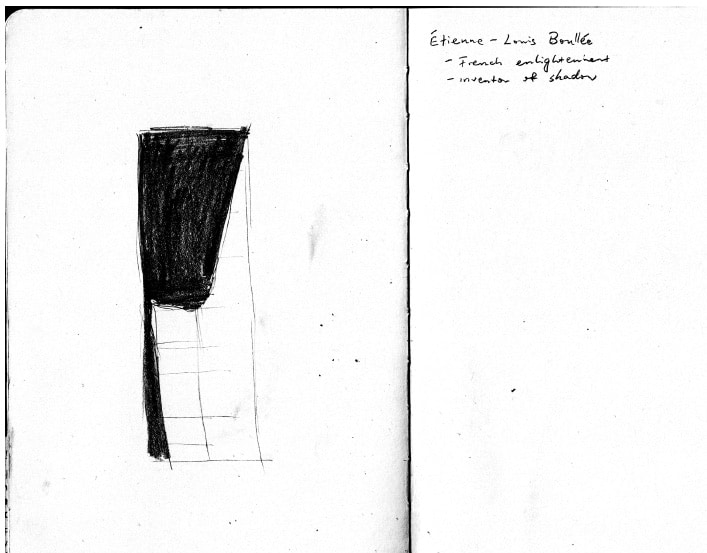

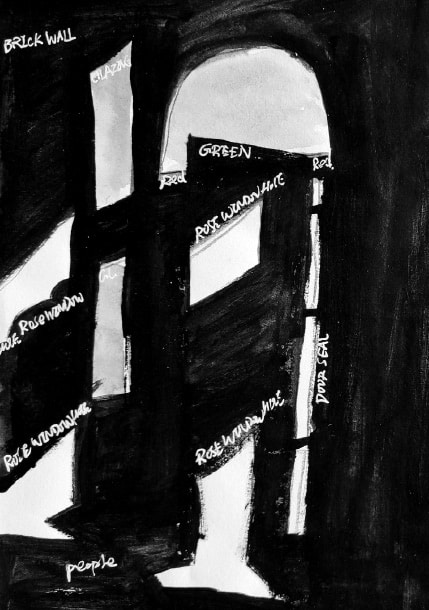

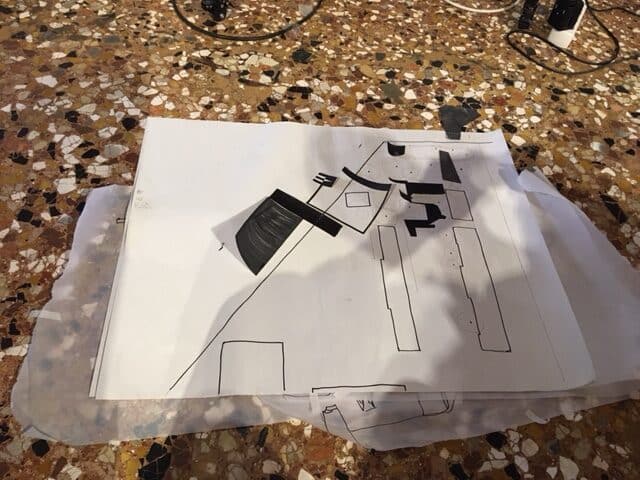

My own group of seven students were asked to harvest Venetian Shadows and to record them in field notebooks, a procedure inspired by the anthropologist Michael Taussig and his book I Swear I Saw this: Drawings in Field Notebooks, Namely my Own. This harvesting of Venetian shadows initiated a somewhat unconventional design procedure. According to Roland Barthes, the role of the phantom, of shadows, is to make explicit implicit modes of experience – edited and summarised experiences of Venice in our case – a technique to avoid the romantic delirium everybody falls into while gliding around on a vaporetto. As Taussig notes, ‘fieldwork activates a sense of failure… a foreboding that recording is always inadequate… but we must remember that it has the potential of a shadow, something invisible and auratic that makes the thing depicted worth depicting’.

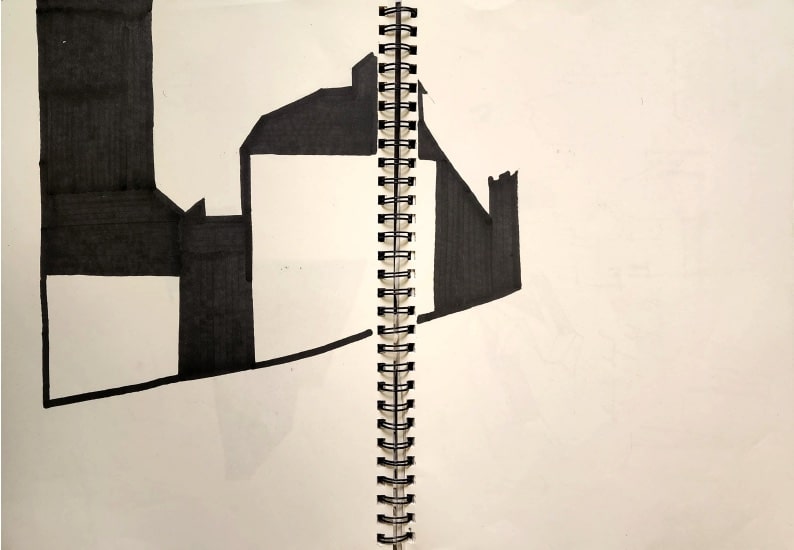

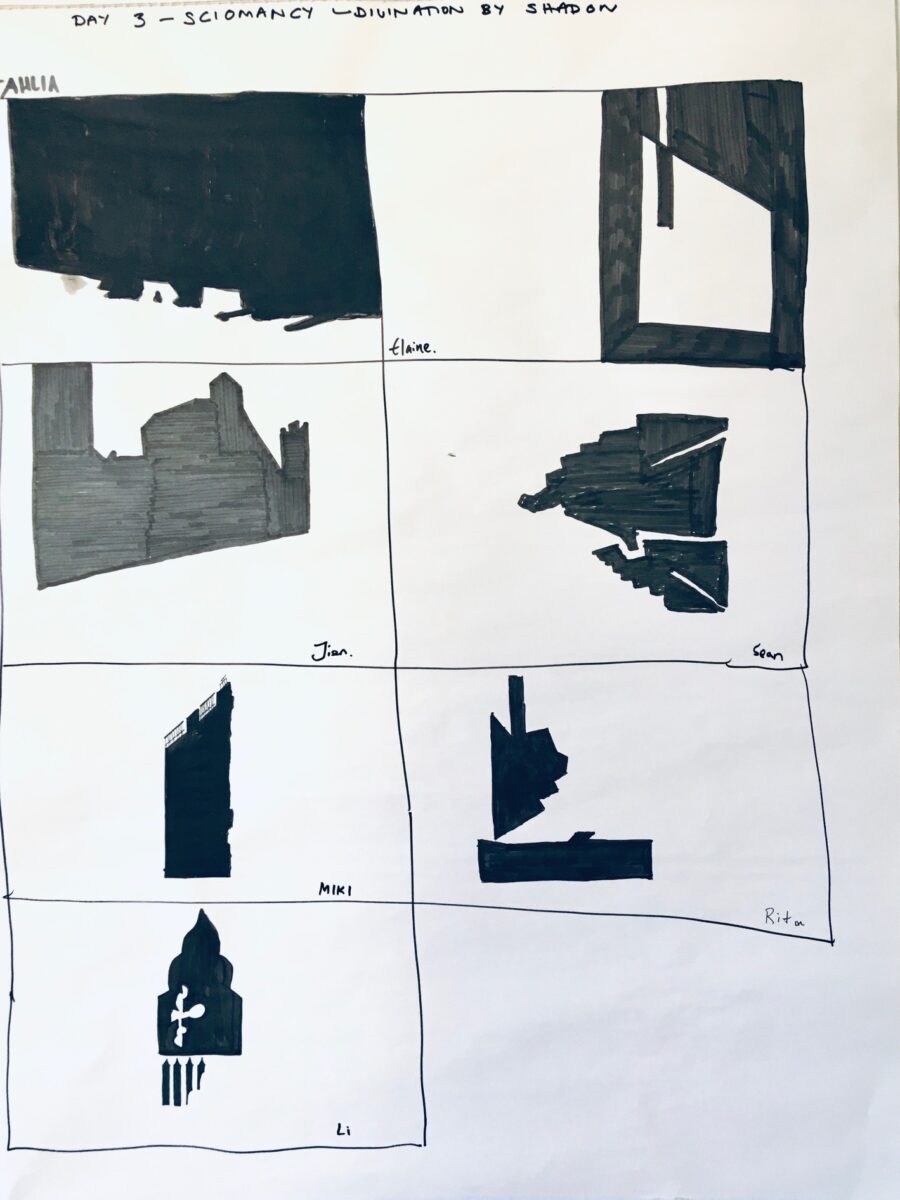

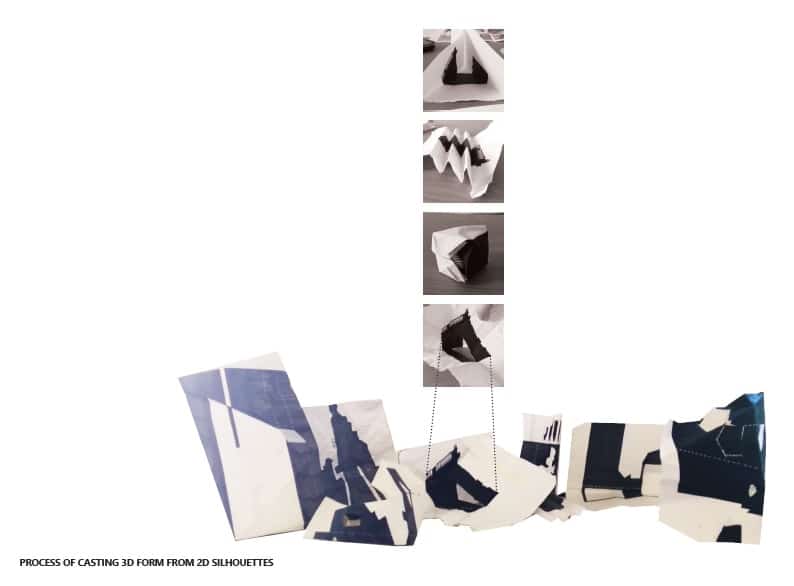

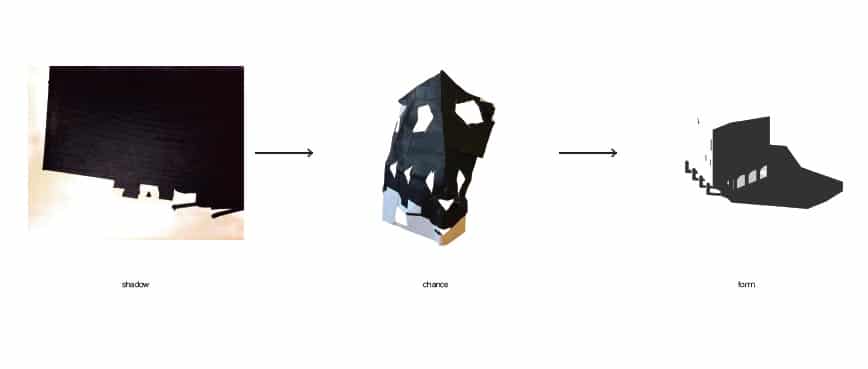

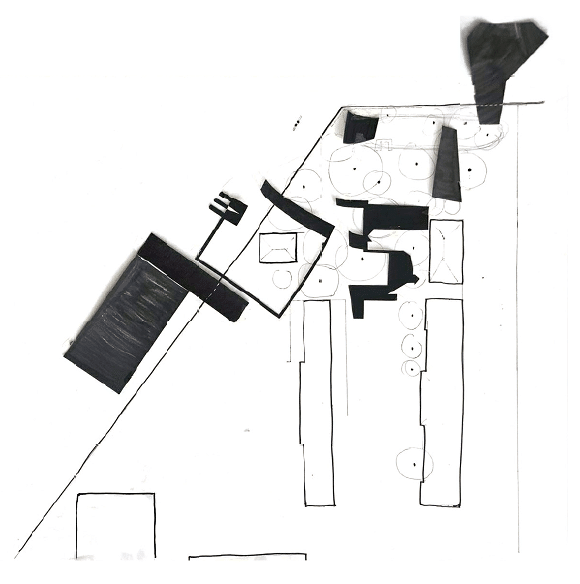

After two days we were able to assemble our first taxonomy of selected shadows. The next question was how to project these two-dimensional figures back up into the third dimension. Folding and programmatic interpretation was needed (Figs 7,8, 9,10) as well as a new word – SCIOMANCY – divination by shadow.

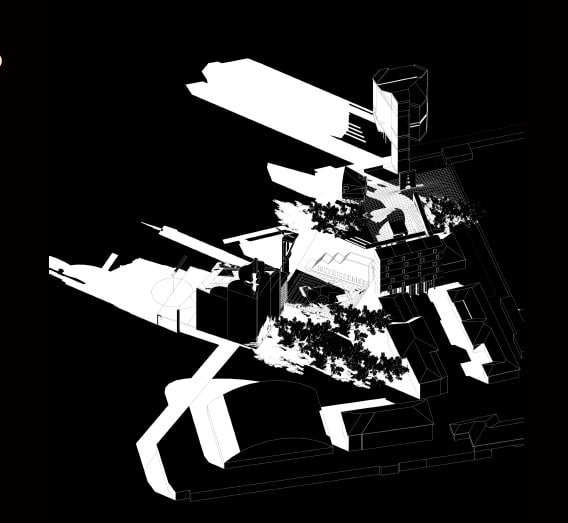

Next the emerging shadow-buildings were tested on the selected site – the north-western corner of Venice (the Cannaregio quartier, not far from the location of iconic Venetian fictions by Hejduk and Eisenman). An overlaying and subsequent close packing of individual projects generated a shadow village typology that proposed much needed facilities for Venetian residents (far from the madding crowds), comprising: a local theatre, a religion-neutral-chapel, workshops and student housing, a waterfront youth-activity-centre, a horticultural cloister with green-house and Scolari Memorial, another neighbourhood-mechanical-boat-parking-shed with adjacent facilities and elevated sun deck.

Students stitched together (with radical white shadows) this Shadow Village for their final presentation and their studio leader (I had skived off early to Iceland) subsequently delivered another Post-Workshop-Director’s-Cut of the conclusive Shadow Village, with backdrop of a familiar Grand Canal sliced Venice topped in the distance by a framing Giudecca.

The reduction of Venice perceptions to shadows and their recording by hand drawing sidestepped the students’ already considerable digital skills to germinate and prioritise an eye-hand spatial engagement procedure. More sophisticated readings, like a suggested mapping of shadows over time, were rejected in favour of the seductive depth of primal blackness and a corporal presence necessary for ‘in the field drawing’.

More information about the Venice Studio Melbourne and Venice Studio 2022, as well as the upcoming studios in 2023, can be found here.