Where to Find a Drawing of a Swiss Gold Vault

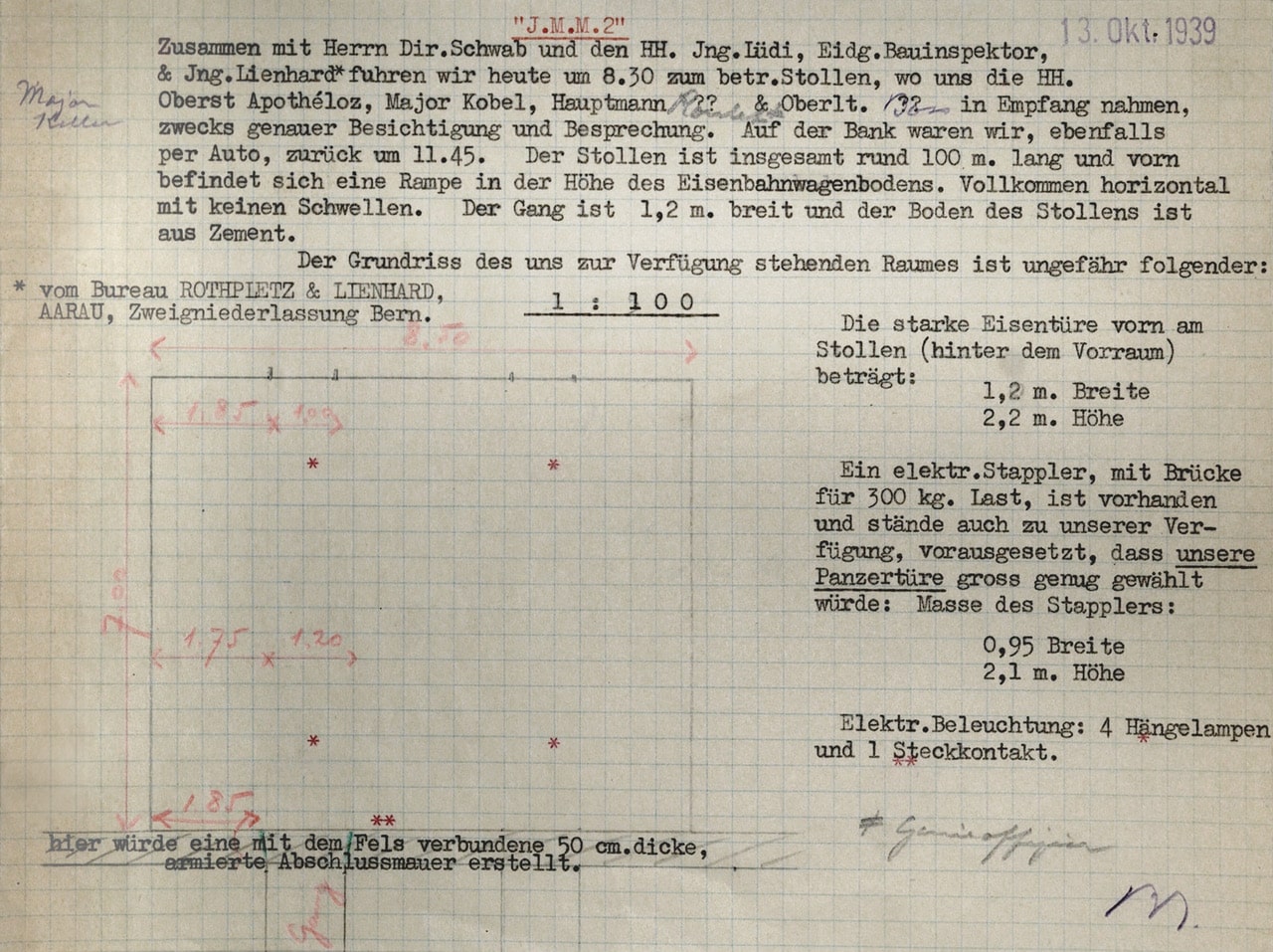

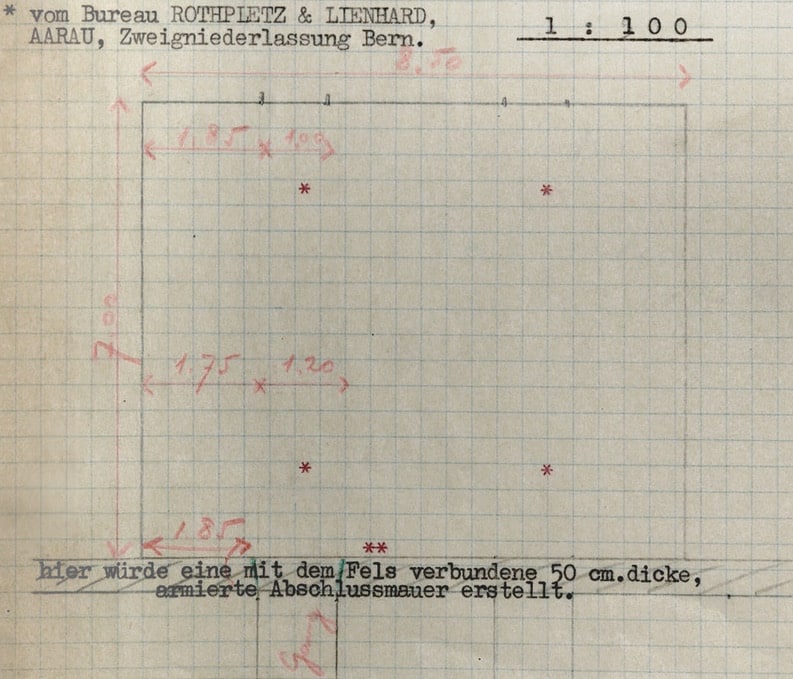

If you really want to hear about where to find the mountain vaults of Swiss banks, and what they look like, the first thing you should probably know is that the archives vigilantly kept by almost all banks in Switzerland are not publicly accessible—and even when they are, the last thing you will find there are architectural drawings.[1] Your best hope is illegible scribbles, in the margins, on the backs of papers, overlooked by archivists, because everything that does resemble a floor plan or section could compromise the security of still-in-place infrastructures. After two years of combing through piles of correspondence, annual reports, and meeting minutes in the archive of the Swiss National Bank, one such document stood out. A yellowed bedraggled piece of paper of approximately 15 by 21 centimetres that, considering its serrated edge, must have been hastily ripped from a block note. On top of the thin, blue-lined grid, there is a palimpsest of data, five consecutively applied layers, bleeding off every corner of the paper. In sharpened graphite grey pencil, the nine lines are ruler-straight, not veering to left or right, clearly from the hand of a precise, fastidious person, but not necessarily from an architect. They make up a rectangular space, an underground cavern, the mountainside accentuated by a hatch, pierced by two access corridors. An assumption confirmed by the fat red pencil, handwritten, probably during a site visit, annotating the space’s internal dimensions of 8.5 by 7 metres.[2]

Back at the office, the torn piece of paper was inserted into the typewriter of one of the secretaries, dated October 13, 1939 (six weeks after the start of the Second World War), and clarified with a caption: ‘the layout of the space available to us is approximately as follows.’ The us refers to the document’s author, who signed his drawing with ‘Bl’ in blue pencil at the bottom right, like an architect signing a drawing. The same ‘Bl’ features on the banknotes that the National Bank issued those years, and identifies its Chief Treasurer Erich Blumer. On top of the memo, there is a red-typed codename, JMM2. The moniker is repeated in later correspondence: ‘a gallery intended for the storage of ammunition, the rear part of which was separated from the front part by a brick wall and made available to the National Bank after the beginning of the war in 1939.’ Our suspicion is confirmed, the sketch indeed represents one of the highly secret Alpine bunkers where the National Bank during the war hoarded its contested Nazi gold.[3]

Paradoxically, drawings, one of the most confidential materials in the archive of the banks, are the most ubiquitous artefacts in architectural archives, while vice versa, spreadsheets, the documents that fill the majority of the shelves in banks are often excluded from the archives of architects, similarly for reasons of confidentiality.[4] This selective curation of both disciplinary-mandated archives questions their continued relevance. The current shifting gaze in architectural history, away from single authorship towards more global, collective, and postcolonial practices underrepresented in the canons of the discipline, often requires archival research to go beyond the instituted frames of architectural archives. But to contain the laborious and costly practice of archiving, the acquisition policy of those archives is often (and increasingly) tightly framed, whether limited to a field such as architecture, an institution, a territory, or to particular types of documents such as meeting minutes, correspondence, or architectural drawings. This fragmentation not only complicates the archiving of architectures that are the result of complex political, technological, and design decisions, such as the Alpine vaults of Swiss banks, but it also serves those who like to keep sinister secrets.

Notes

- Sentence structure echoes the opening line of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye: ‘If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is…’ J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (London: Penguin Modern Classics, 1979), 1.

- The sources used for this paper are retrieved from the public Swiss National Bank archive, unless mentioned differently.

- For an elaboration on the contested gold transaction between the Swiss National Bank and Nazi Germany see: Bergier et al., Switzerland, National Socialism, and the Second World War: Final Report, (Zurich: Pendo Verlag, 2002).

- For example, in the archive of MVRDV, kept by the Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, there are only four small dossiers from the office’s administration, one of them being a cashbook from the first years of its founding. When asked about this document, one of the founders was worried about the sensitive content of the cashbook. Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, MVRDV / Archive, inventory number MVRVTP000.1.

Ludo Groen is a doctoral candidate and assistant at ETH Zurich’s Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta). As part of the SNSF-funded research project ‘Switzerland. A Technological Pastoral,’ his doctoral research describes the secretive characters, spaces, and landscapes behind the extraction, trading, and vaulting of gold in and outside Switzerland. He previously worked at the Berlage in Delft and the Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam.

This contribution builds upon the author’s doctoral research, supervised by Laurent Stalder and Milica Topalović. A version of this text was previously presented at the Jaap Bakema Study Centre annual conference ‘Architecture Archives of the Future,’ organised by Dirk van den Heuvel, Alejandro Campos Uribe , and Fatma Tanış.

This text is one of the selected responses to the Open Call: Storytellers, Observed—an inquiry into the origin and circumstances of a single drawing (or series of drawings), observing the ways by which each achieves the specific purpose for which it was made. For further information click here.

From the Drawing Matter Collections.