William Dickinson’s Pocketbook: Rethinking Drawing & practice in Early C18th England

During the upheavals of the Civil War, Westminster Abbey had functioned as the church of the state for the Commonwealth. Upon the Restoration of Charles II, the Abbey resumed its historic role as the coronation church for English monarchs. [1] Parliament voted towards restoring the fabric, reinstituting its monarchical function and symbolic status. Sir Christopher Wren, the Surveyor-General of the Royal Works, was appointed to oversee the restoration of the Abbey in 1699 and recruited William Dickinson to assist him in surveying the site and its immediate vicinity, repairing its fabric, improving nearby streets, and erecting western towers. [2] Dickinson, who had been working in Wren’s Office for about eight years, played a crucial role in restoring the Abbey to its former glory. His principal job on site was to record and report on the Abbey’s ‘ancient and ruinous Structure’ and to provide workmen and craftsmen with measurements needed to perform work on site.

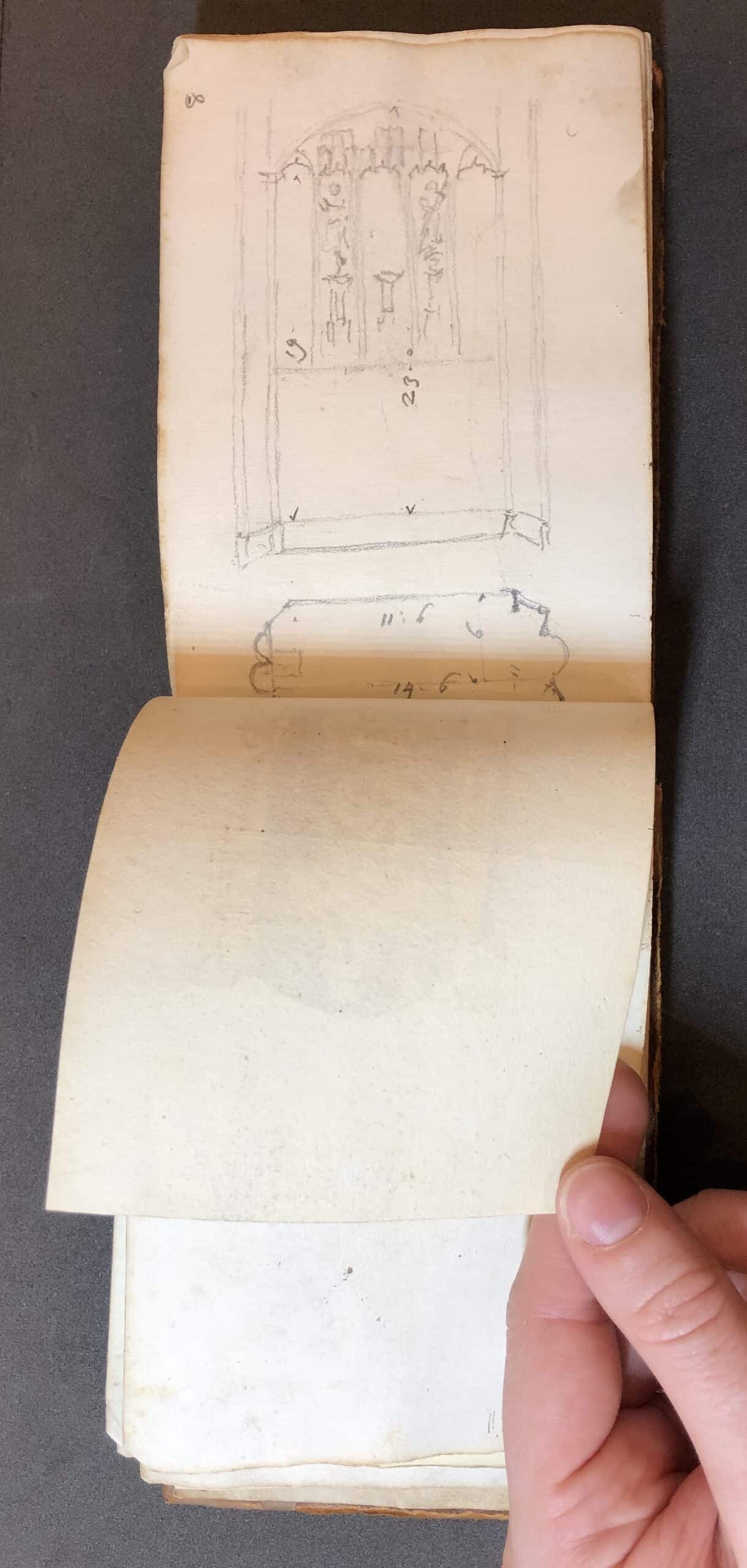

Beginning in the autumn of 1700, he turned to the Henry VII Chapel to survey its high-gothic interior which became the focus of his work for the next several years. To perform these surveys, he used a small pocketbook bound with blank pages. The pocketbook, in the collection of the Bodleian Library, is diminutive for a surveyor’s pocketbook. It measures just 95mm tall by 145mm long. He started using it in c.1698–9 at St Paul’s when he was assisting Nicholas Hawksmoor in making drawings for the cornices of the church’s dome. A year later in Westminster, however, he used it for meticulously studying the historic gothic architecture of the Abbey.

One of those studies included recording the dimensions of one of the bays in the Henry VII Chapel in preparation for the tomb of William III and Mary II. After the death of King William III in March 1702, a monument was to be erected in William and Mary’s honour. He measured the space and then made a cursory pencil sketch of the elevation, noting the height, width, and depth of elevation and plan of the aisle bay.

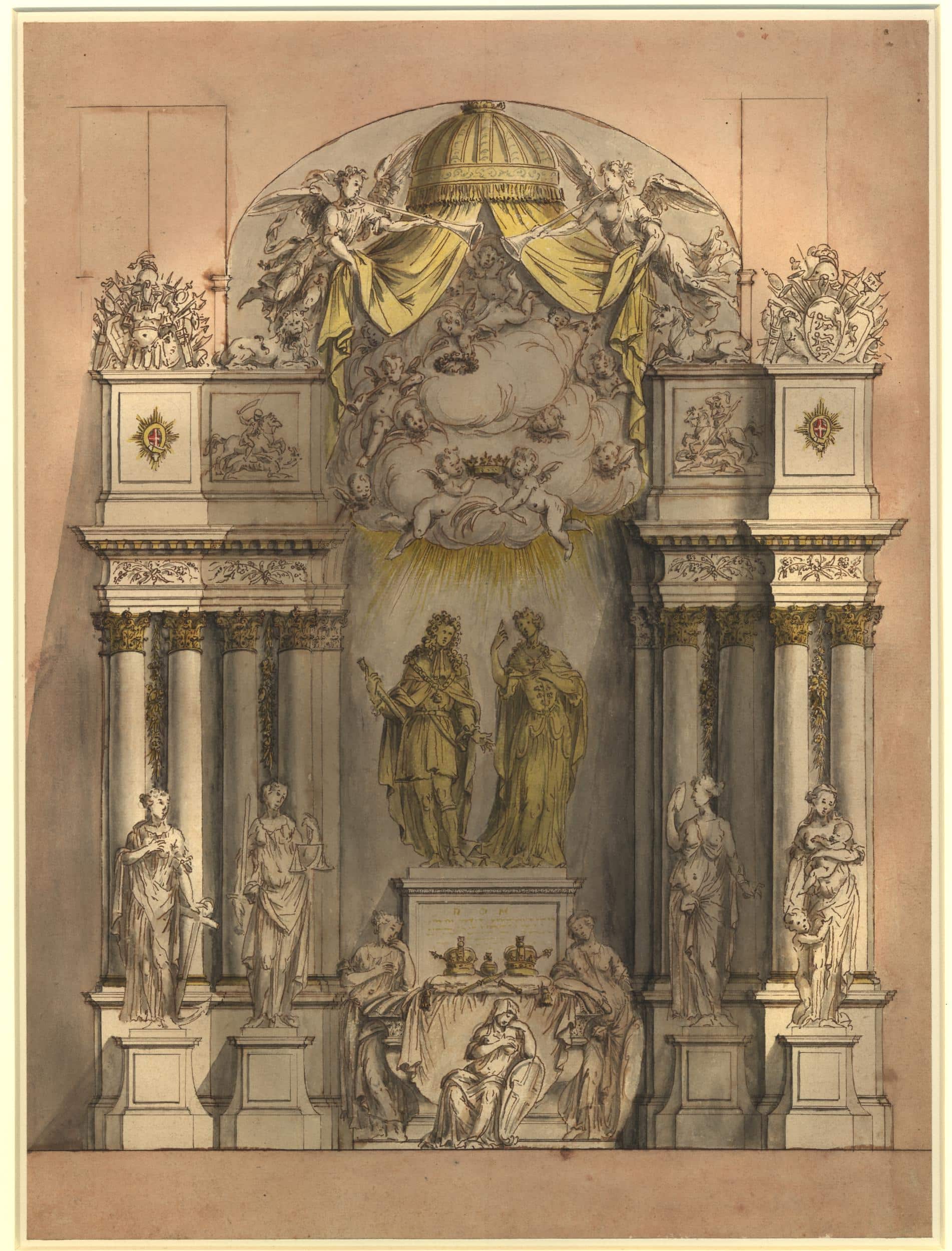

With a pencil, he gave an impression of the chapel’s gothic architecture and carved statuary that would sit behind the proposed monument. The monument to be installed in the aisle was to be made by Grinling Gibbons, the king’s Master Carver. He drew a design for the tomb after an earlier tomb he had prepared after the queen’s death in 1695. [3] The design features a triumphal arch with statues of King William III and Queen Mary II on central pedestals. Britannia and the four Virtues (Hope, Charity, Prudence, and Justice) stand on shorter pedestals amid a cluster of coupled Corinthian columns supporting military trophies. Framing the king and queen is a baldachin and drapery with flying putti clenching the royal crown.

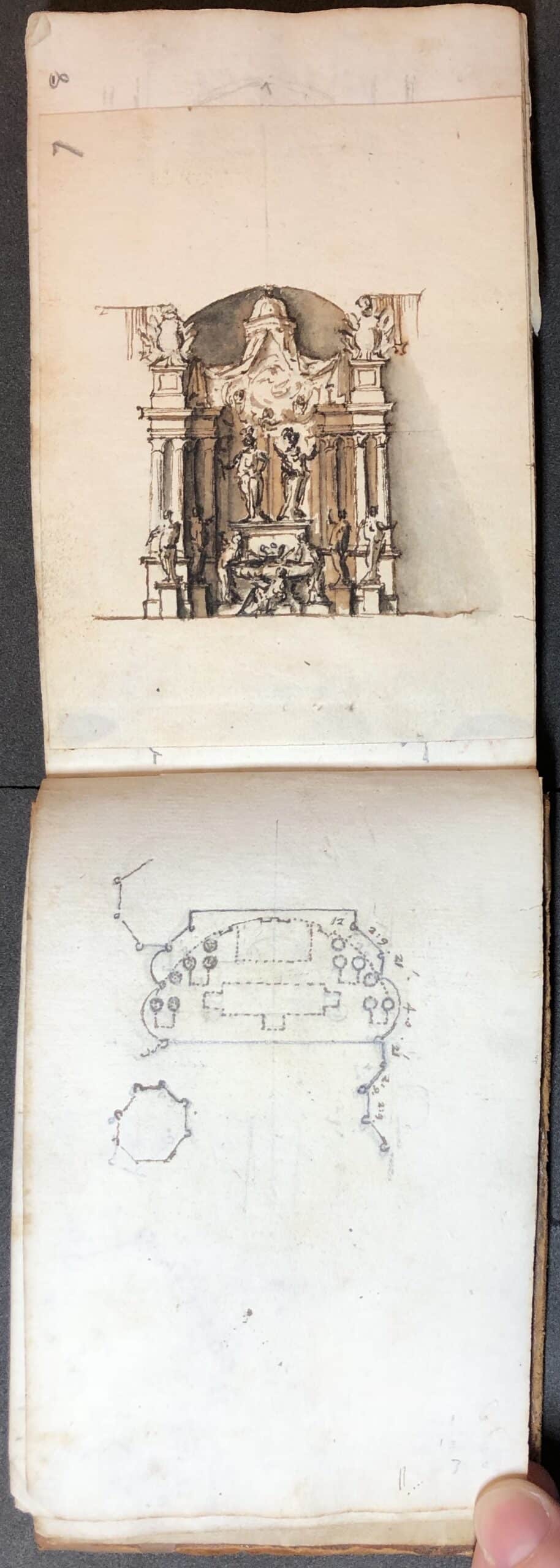

Dickinson and Gibbons must have met at some point to confer over the dimensions of the side aisle and proposed design, for a study in his pocketbook shows a copy of the monument. Dickinson therefore must have seen some version of Gibbons’ design. Perhaps he saw the extant, highly finished design drawing or another earlier study for it. [4]

To make the small study, Dickinson first cut a small scrap of office paper to fit over his pencil sketch elevation. Then he pasted the scrap onto the elevation with two dabs of red sealing wax (what they called ‘wafer’). With a pencil, he made featherlight marks to position the monument within the dimensions of the chapel bay. Then, he thoughtfully sketched a copy of Gibbons’ design in pencil with far less haste than the elevation he drew before. He drew more slowly and defined features of the design despite the study only measuring just over 60 by 60 mm. He traced over his preliminary pencil lines with a very fine quill dipped in black ink to articulate the architecture of the colonnade, as well as the figures, trophies, baldachin. Then, with another quill dipped in dark brown ink, he drew a ground line of the chapel floor and the existing architecture of the chapel walls that would frame the monument. Finally, he applied two layers of wash for which he would have used a very fine brush. The first wash applied was done with a mixture of brown ink diluted in water. He applied it above the baldachin and behind the king and queen. Over this first wash, he applied a second, denser wash. He applied a wash of carbon black ink diluted in water on the upper left of the arch and down into the colonnade on either side of the former monarchs. With a more transparent wash, he pulled his brush down on the right side of the monument onto the proposed wall to highlight the structure. Incorporating both black and brown ink into his study emulates the style of draughtsmanship Gibbons exhibited in his design drawing. On paper, Gibbons regularly used combinations of brown and black inks with combinations of saturated and subtle ink washes to create dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, form, and mass. What we see then in Dickinson’s miniature study of Gibbon’s design is an assimilation of drawing style and technique passed from craftsmen to architect.

After affixing his small-scale study of Gibbons’ monument into his pocketbook, Dickinson drew a fine line in pencil down the centre of the study, over the gutter of the pocketbook, and across the facing page. From this central datum line, he drew a plan of the bay aisle incorporating the dimensions of Gibbons’ monument. The result of this exercise in copying, pasting, and layering drawings emulates the disposition of the architectural forms in the real space of the chapel. Let me explain: Dickinson inserted his study of the monument between a plan and elevation. In positioning the monument in its physical context, between the vertical of the elevation and the horizontal of the plan, Dickinson was using the book to negotiate how Gibbons’ design would fit into the existing historic fabric of the chapel; the book aided his abilities to integrate the new into the old. The form of the pocketbook and the layers of its pages, in other words, provided a platform for Dickinson to contemplate architectural space. His layered drawings furthermore recover a kind of everyday collaboration that occurred in Wren’s Office and recovers a specific meeting between Dickinson and Gibbons. Close observation of Dickinson’s miniature study exemplifies how drawing skills could be learned and exchanged at the drawing table within the setting of the office.

This text on William Dickson’s pocketbook is a further examination of the object that builds Deans’ article ‘Rethinking Drawing and Office Practices in Early Eighteenth-Century England: A Study of William Dickinson’s Pocketbook’, published in the Georgian Group Journal (Vol. XXIX).

Notes

- This event was memorialised in a print by Wenceslaus Hollar’s published in John Ogilby’s The Entertainment of His Most Excellent Majestie Charles II (London, 1662).

- WAM (Westminster Abbey Muniments) 34501, f. 84.

- Cf. Drawing 276 in Anthony Geraghty, The Architectural Drawings of Sir Christopher Wren at All Souls College, Oxford: A Complete Catalogue (Lund Humphries, 2007); See also D. Green, ‘Grinling Gibbons: his Work as Carver and Statuary 1648-1721’, (London, 1964), pp. 74, 164.

- Cf. An earlier design for the monument tomb for Mary II from c. 1694-5 is at All Souls, Oxford. Geraghty, All Souls Catalogue, no. 438. This design was significantly changed by Gibbons upon the death of King William III.