The Measure of It: An Essay on Measured Drawings

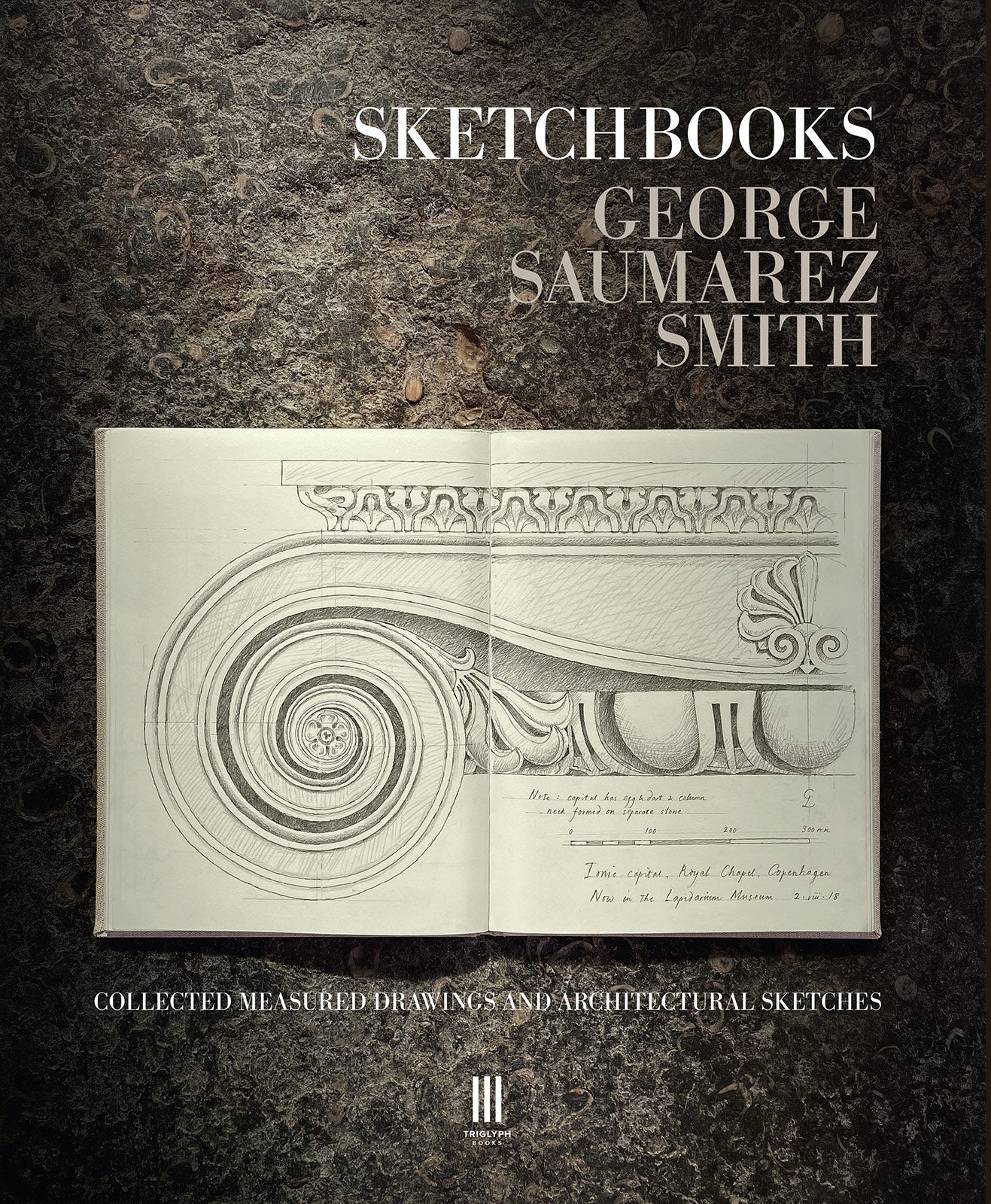

As a classical architect, George Saumarez Smith not only believes in producing something that is pleasing to the eye, but in the importance of precise measuring in architectural practice, that ‘…the important part of an architect’s role is to produce drawings as instructions to a builder’. The following excerpt is taken from Saumarez Smith’s book, Sketchbooks: Collected Measured Drawings and Architectural Sketches, from the introduction, ‘An Essay on Measured Drawings’, where his gives an insight into his process. Purchase Sketchbooks from the publisher, Triglyph Books, here.

As the years have gone on and time has become more pressured, I have increasingly relied just on drawing in pencil. A bottle of ink is quite a risky thing to carry in one’s luggage, and the nib of a dip pen is easily damaged. I have found that a sharp HB or B pencil, if used firmly enough, can give a similar quality to an ink line.

I start the drawings with the main setting-out lines measured off the edge of the page and drawn against a scale rule. These form the skeleton of the drawing, and after that I gradually fill in the detail freehand which gives the drawings a softer quality than a ruled line drawing.

Although I have become quicker at drawing there is no getting around the fact that measuring is a time-consuming process. I have always used a normal steel tape rather than any digital measuring device as I like the challenge of balancing a tape measure to reach sometimes unlikely places. The only other tools needed are a scale rule, a good pencil – I generally use an automatic pencil with a 0.5mm lead – and an eraser.

The drawings are all done on site so that I can be sure that I have got everything down on paper. Most of the drawings in this book have taken two or three hours to produce, often with the finishing touches being done at a table in a nearby café. I have also realised that if the drawings are ever to be reproduced it is not enough for them to be drawn to scale in the sketchbook; they also need a scale bar added somewhere on the drawing and sometimes also a north sign for plans of buildings.

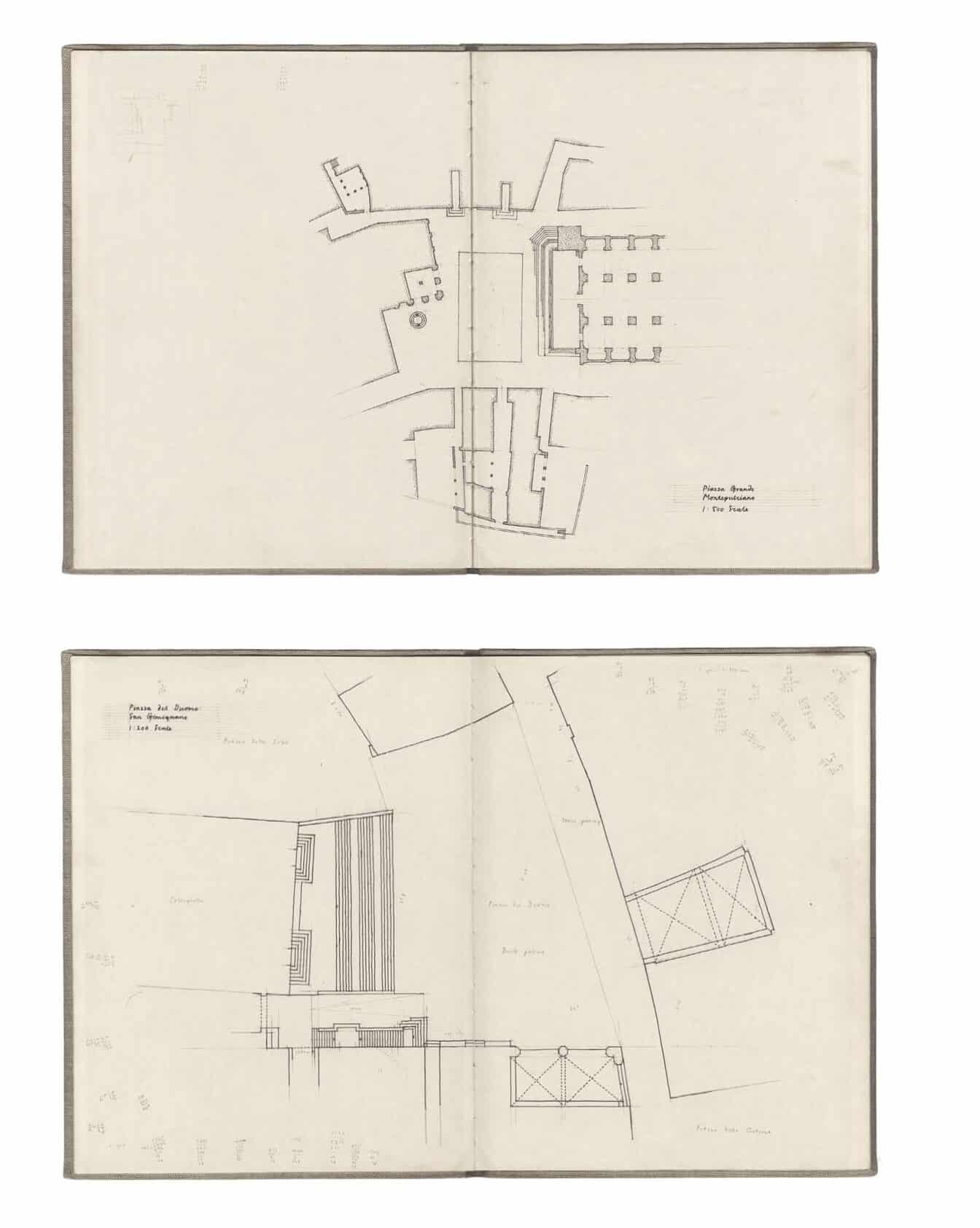

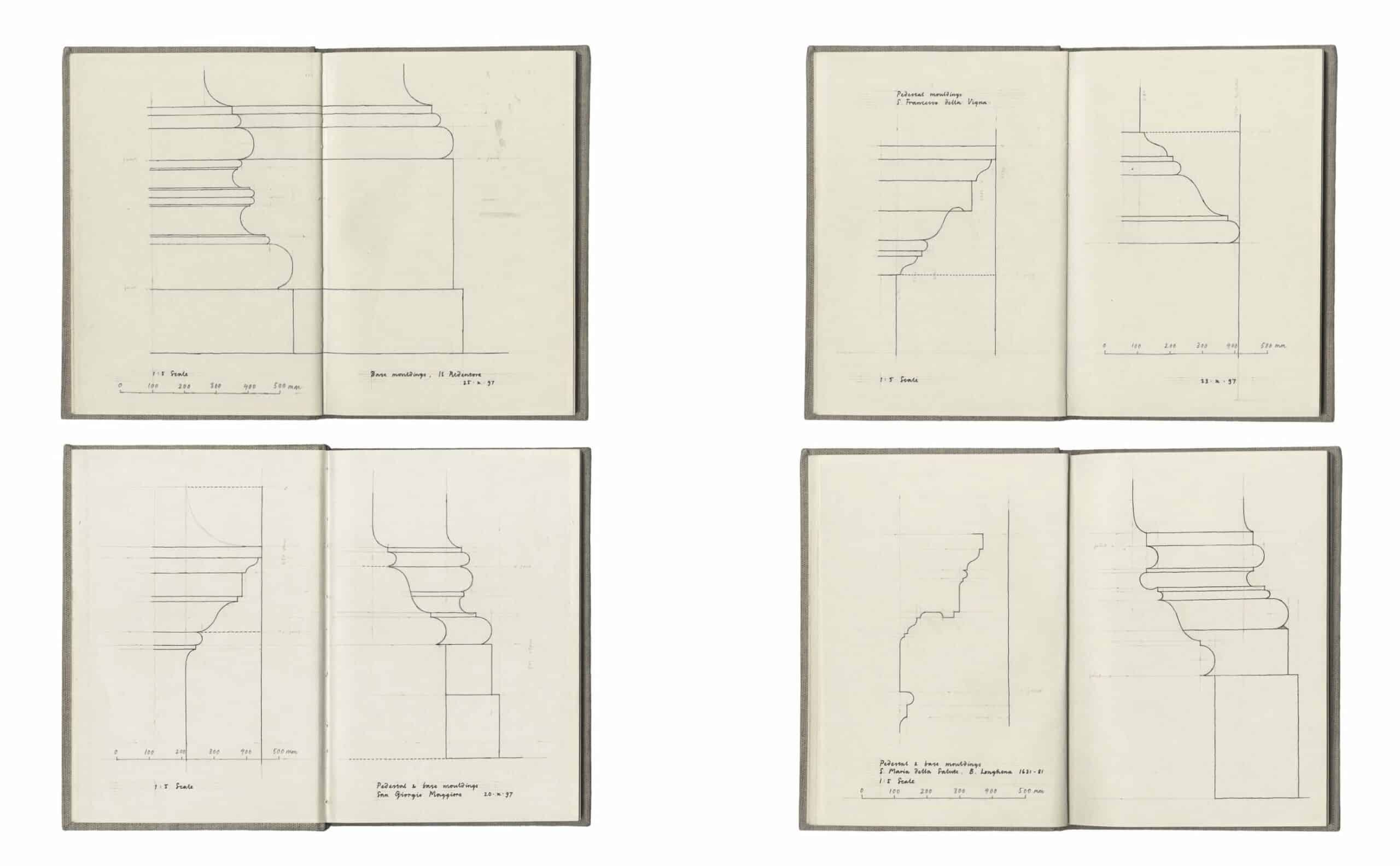

Key to all of these drawings is the choice of the right scale. I measure everything in metric dimensions and use the recognised scales of 1:500, 1:200, 1:100, 1:50, 1:20, 1:10, 1:5 and full size. Different subjects lend themselves to different scales so that, for instance, 1:5 is an ideal scale for part of a floor pattern whereas the façade of a building will work better at 1:50 or 1:100.

At the beginning of the drawing process, it is helpful to visualise what it will look like when finished: in other words, to design the drawing on the page before going too far. In this process I always try to make maximum use of the paper. As the size of the sheet is the full extent of an open sketchbook, many of my drawings are drawn across the seam which takes some getting used to. However, it means that the larger sketchbooks, when folded open, are able to take full size drawings of details such as chair legs.

Sennelier sketchbooks come in a variety of different sizes, so I have a range of books to choose from when I am travelling. I have found the most useful size is 215mm x 270mm, but the larger sketchbooks are good for complex subjects and the smaller sketchbooks are good for very quick drawings. I often travel with two sketchbooks of different sizes so that I can choose on the spot which is best suited to a given subject.

Once drawings are complete, I photograph or scan them in case the sketchbook ever gets lost. This has only happened once; about five years ago I had a bag stolen from my car with the Titus sketchbook inside. Fortunately, most of the drawings had been photographed and some are included within this book

II

The most frequent question I am asked by students is how I decide what to draw, and the short answer is that I like to measure anything that is elegant and well-designed. It does of course also need to be easily accessible without the need for scaffolding or ladders.

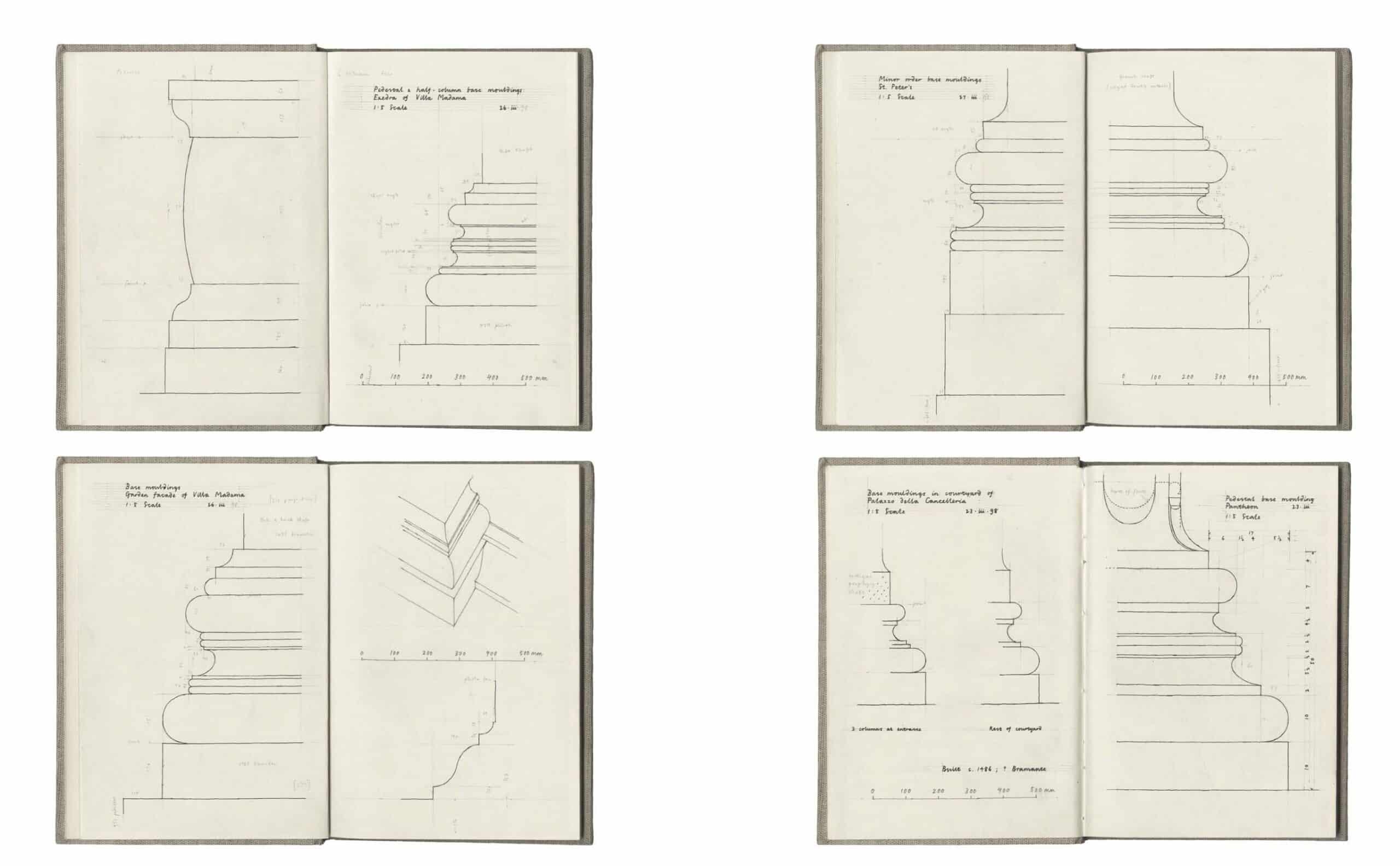

I have measured things across a wide variety of different scales. On a trip around Tuscan hill towns in 1997 I measured the main public squares in Montepulciano and San Gimignano, while on a trip to Rome in 1998 I spent two weeks just measuring the mouldings of column bases.

Pedestal mouldings, facade of San Francesco della Vigna, Venice, 1997 (top right); pedestal and base mouldings, facade of Santa Maria della Salute, Venice, Italy, 1997 (bottom right). Courtesy of the Author and Triglyph Books.

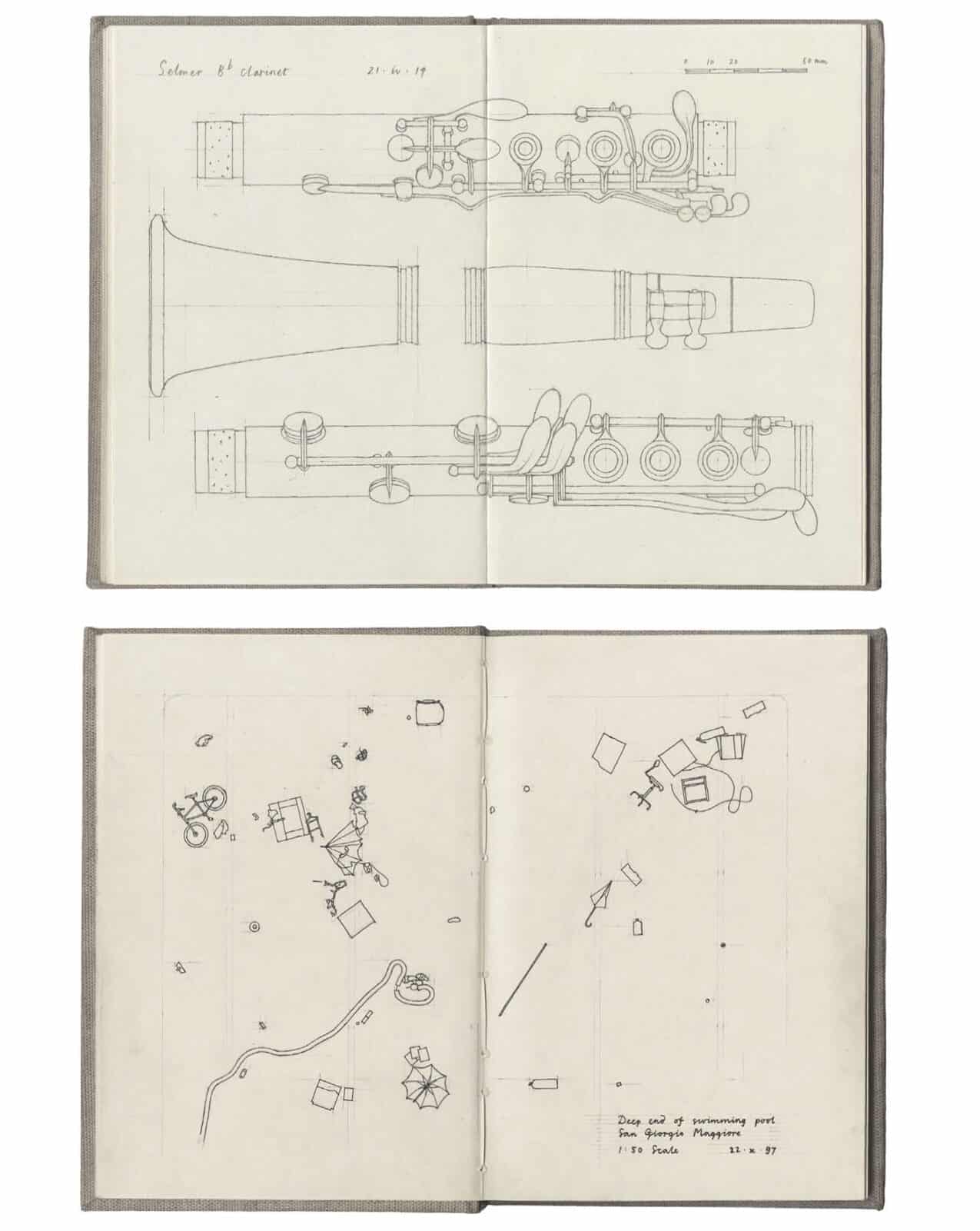

It can be reassuring to measure things that have been studied many times before, such as the column bases of the portico of the Pantheon (page 85). But I also like to seek out less obvious subjects, things that might conventionally be overlooked. Occasionally there are fairly extreme examples such as a measured drawing of the contents of an abandoned swimming pool in Venice made as part of a project in my final year at university (page 195). This is explained in more detail at the beginning of Chapter IX.

Minor order base mouldings, Nave of St. Peter’s, Rome, 1998 (top right); base mouldings in courtyard of Palazzo della Cancelleria, Rome, and base mouldings to Portico, Pantheon, Rome, Italy, 1998 (bottom right). Courtesy of the Author and Triglyph Books.

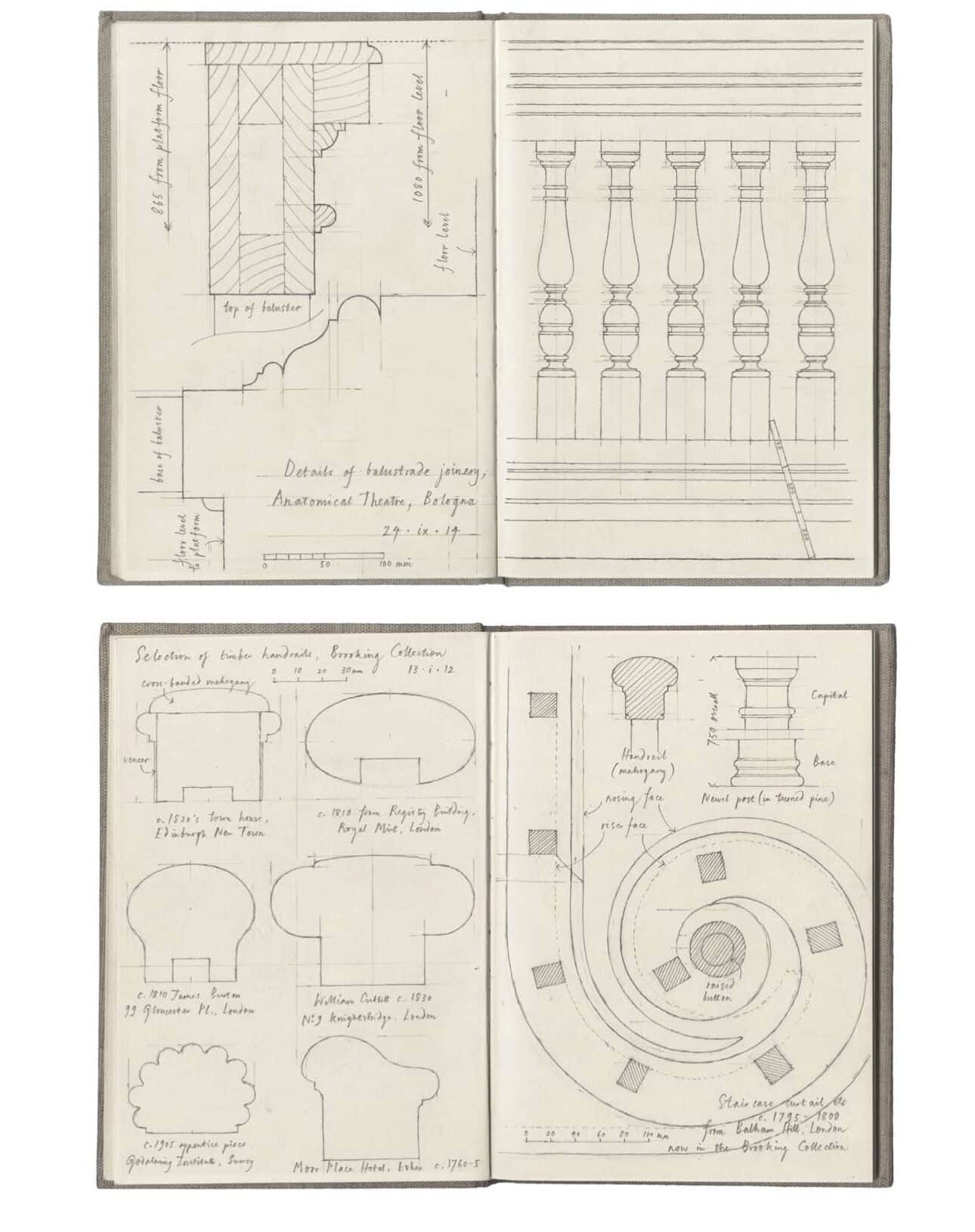

Some things particularly lend themselves to measuring. Balustrades of staircases, being at a convenient height to draw and often decorative in their design, work very well in a medium-sized sketchbook at 1:5 scale. I like drawing things at full size where possible and occasionally I will measure non-architectural things like the pieces of a clarinet in their box (page 195).

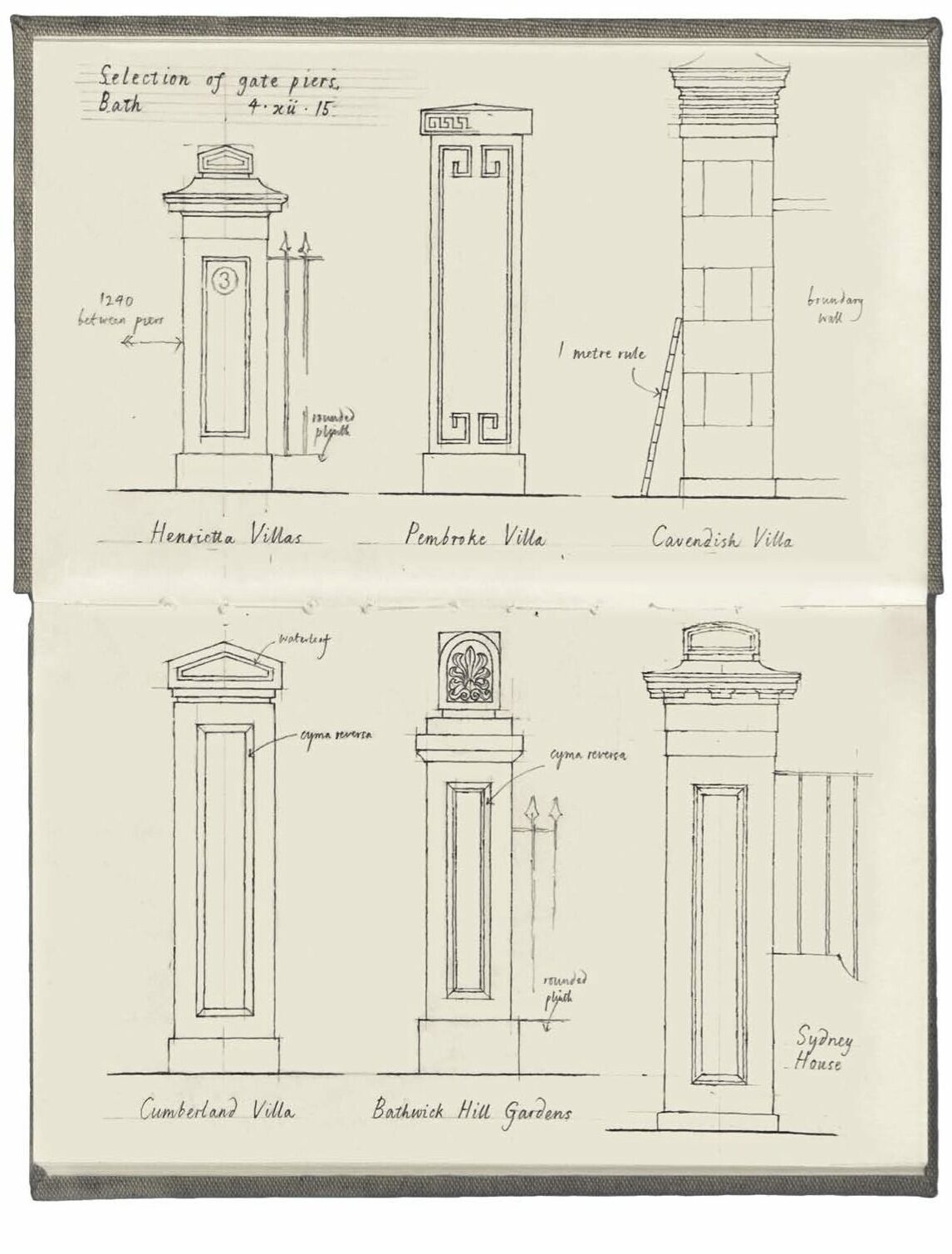

Occasionally it is possible to measure several similar objects together on one sheet, making a very clear comparison in their design. This is similar to the tradition of putting different types of column design alongside one another, known as a Parallel. Examples have included different examples of handrail profiles, gate piers in the city of Bath, or shapes of plastic water bottles.

George Saumarez Smith with be delivering the seminar ‘Lessons in Classicism from the End of a Tape Measure‘ as part of a seminar series organised by the Centre for the Study of Classical Architecture, Cambridge University. The seminar will be held in person and streamed via Zoom. Full details about this event – and others in the series – can be found here.