Theodore Conrad and Harvey Wiley Corbett

– Jennifer Gray and Irene Sunwoo

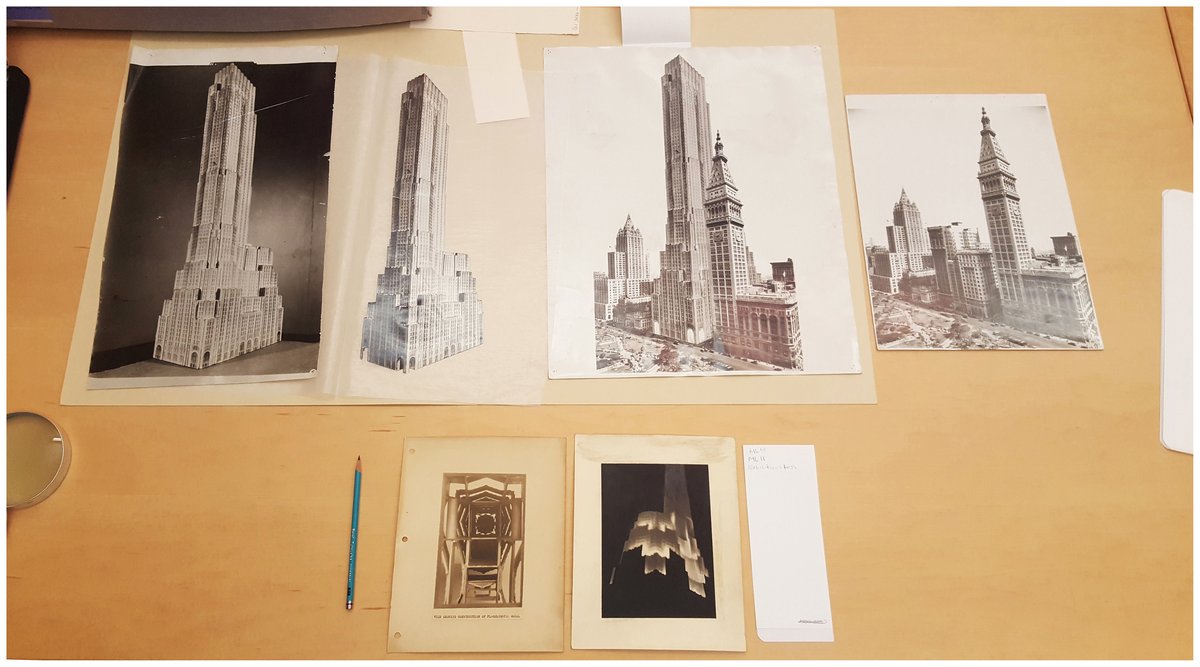

The fragment of Theodore Conrad’s 1929 cardboard model of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company tower designed by Harvey Wiley Corbett (1873–1954) — featured in the current exhibition Model Projections at the Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery at Columbia GSAPP — marks an early episode in the American model maker’s career and an experimental moment in the design development of one of Corbett’s most significant architectural projects. Though the architect envisioned a 100-storey telescoping tower on Madison Square Park in New York City — then the tallest structure in the world — only the 30-storey base of the building was realised. Ironically, the unexecuted tower is the only portion of the model that survives. It is comprised of cardboard pieces, glued together, with windows and architectural details drawn in pencil and watercolour. It is a curious object: a hybrid model and drawing. Handwritten numbers on the facade mark the storeys — perhaps to confirm that the designer and model maker had accounted for every floor of the soaring the tower in this three-dimensional representation.

Conrad began working in the office of Harvey Wiley Corbett, an accomplished architect of skyscrapers, while studying architecture at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn during the late 1920s. There he began what would become a prolific model making career by learning how to construct architectural models out of cardboard — a process Corbett had detailed and extolled in a series of articles published in the journal Pencil Points in 1922. Titled ‘Architectural Models in Cardboard’, the articles included instructions for cutting and scoring cardboard, tips for creating Ionic and Doric column details, recommendations for tools — tweezers, clamps and nozzles — and material suggestions for landscaping effects and scale objects, such as trees and cars. More than just a guide for making architectural models, Corbett’s articles made a broader argument for a shift in architectural representation: compared to architectural renderings, which offered limited information about a building and often appealed to fantasy, he claimed that photography of cardboard models produced more comprehensive and accurate imagery that could nourish the design process, helping architects to imagine a building in its future site. The set of artefacts on display in the exhibition explores this convergence of representational techniques.

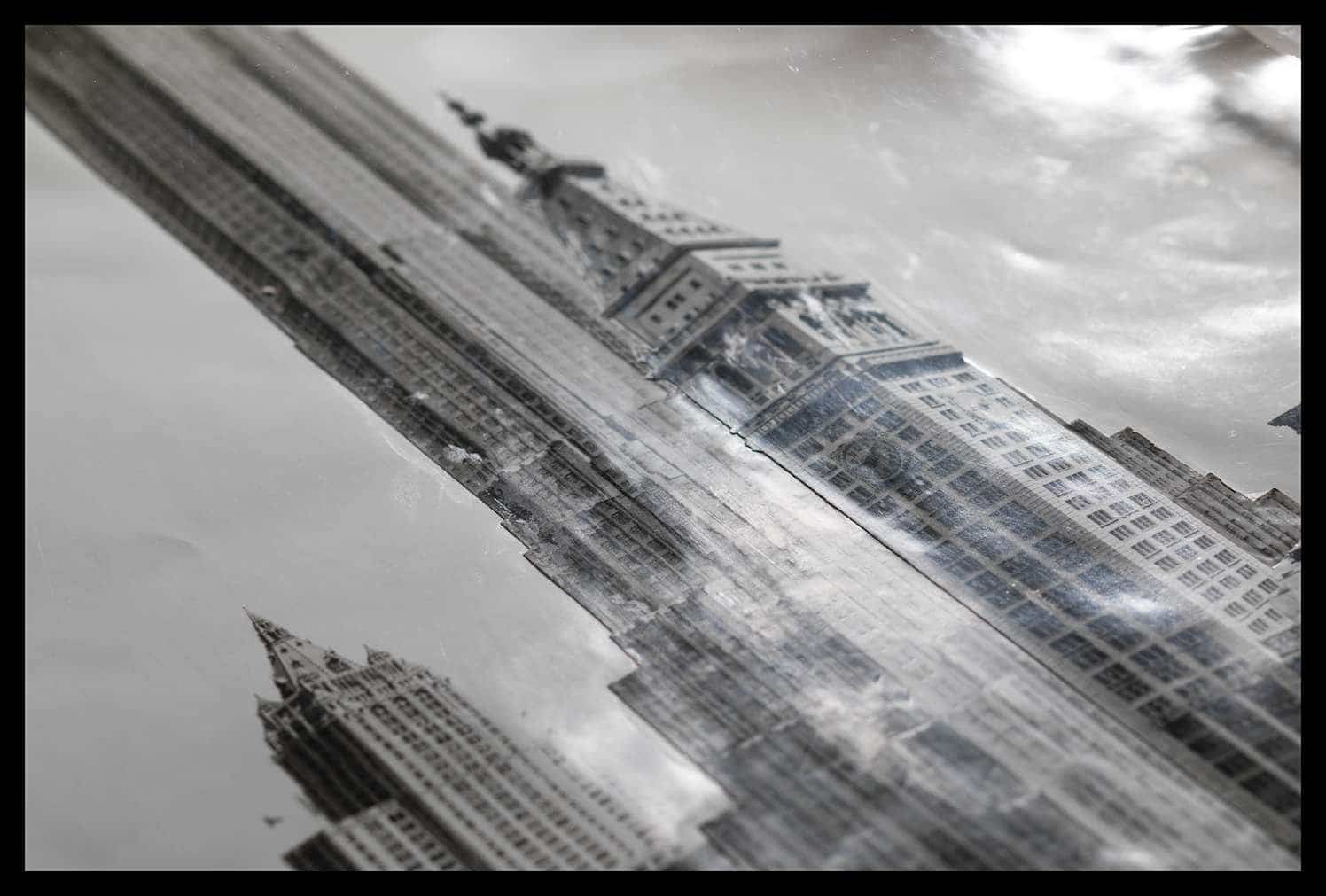

A sequence of photographic proofs and a photo collage from Corbett’s archive, housed at the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, document the complete model and provide insight into how multiple forms of representation fuelled Corbett’s design process. A photograph of the full model (likely shot in his studio) reveals that the wooden pole on the underside of the tower model would have fit into a separate model of the building’s base. In a second print of this photograph, the model has been cut out from its background so that it appears as a freestanding object. This model imagery culminates in a photo collage: the Met Life model has been cut and spliced into a photograph of the existing building site. The resulting composite is a near seamless integration of current and future development — an analogue process that prefigured contemporary digital rendering. More than documents of objects and sites, these images were experimental design tools. Indeed, the pinholes and irregular edges of the photographs suggest that they were attached to Corbett’s studio walls to inspire and provoke discussion.

Reunited on the occasion of Model Projections, the cardboard model and model photographs of the Met Life tower together present a rich, introductory case study in the exhibition, which explores the complex pathways between architecture and its representations through an examination of the practice of model making. Drawing from multiple special collections at Avery Library — including the archives of Conrad and Corbett, as well as Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and photographer Louis Checkman — the exhibition traces an ecosystem of architectural model making during the mid-twentieth century. At its centre is Conrad, whose material experiments and specialised production techniques offer a framework for questioning the relationships between technology and craft, authenticity and authorship, architectural vision and systematised labour. Exploration of these ephemeral registers of architectural production reveals that the model itself was a site of collaboration, negotiation and speculation — not unlike the full-scale building that it anticipated.