The Usonia Plot at Pleasantville

A PROJECT SCRAPBOOK

– Editors

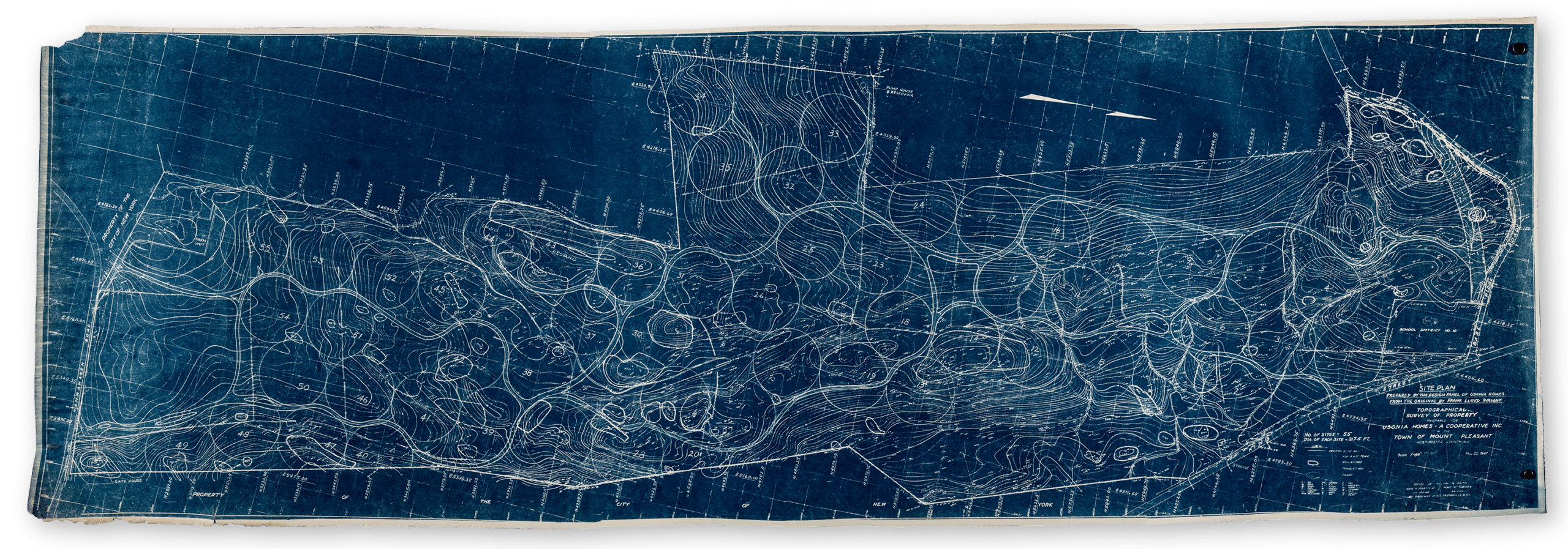

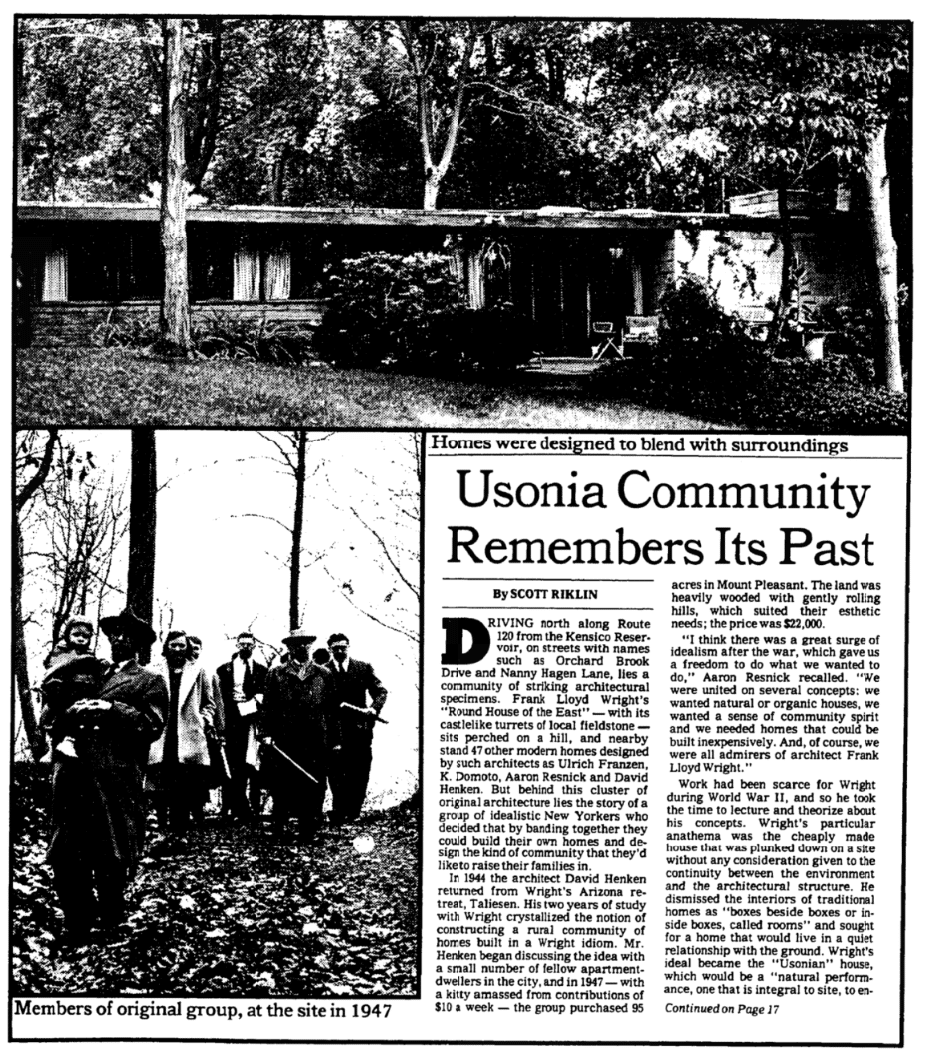

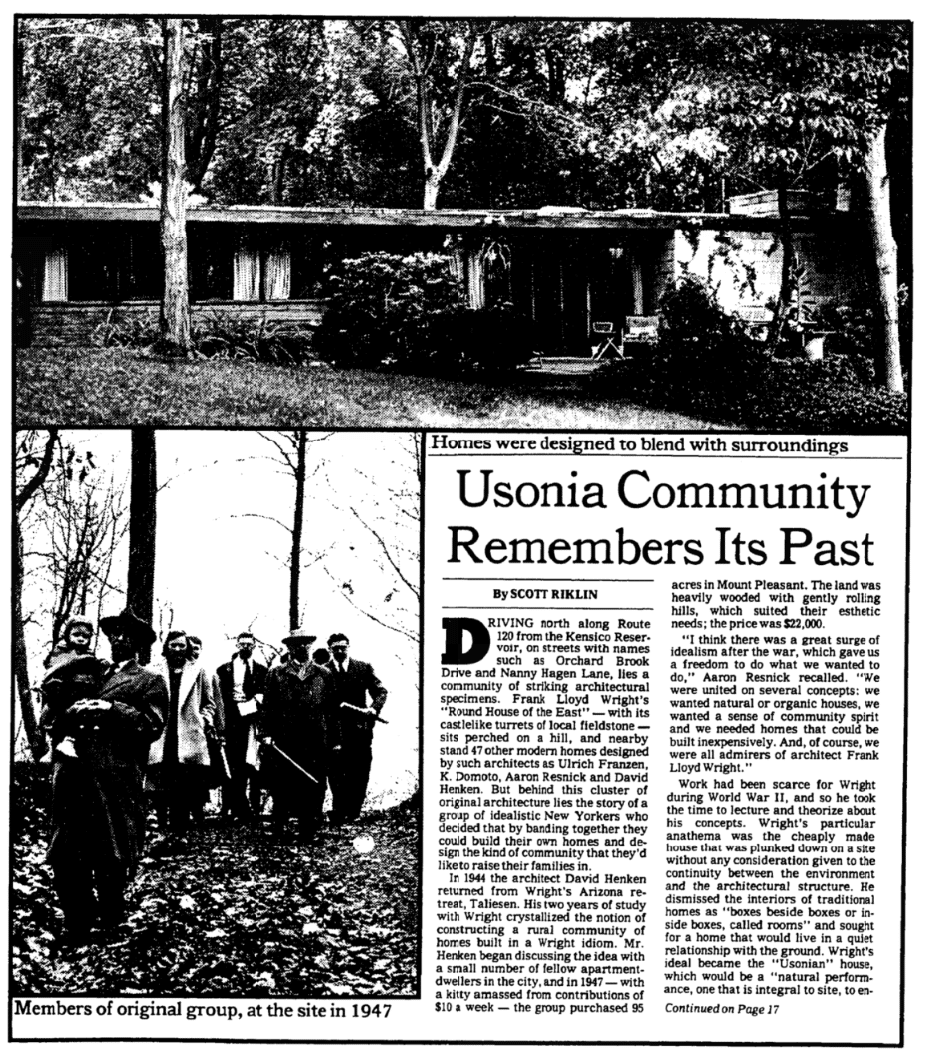

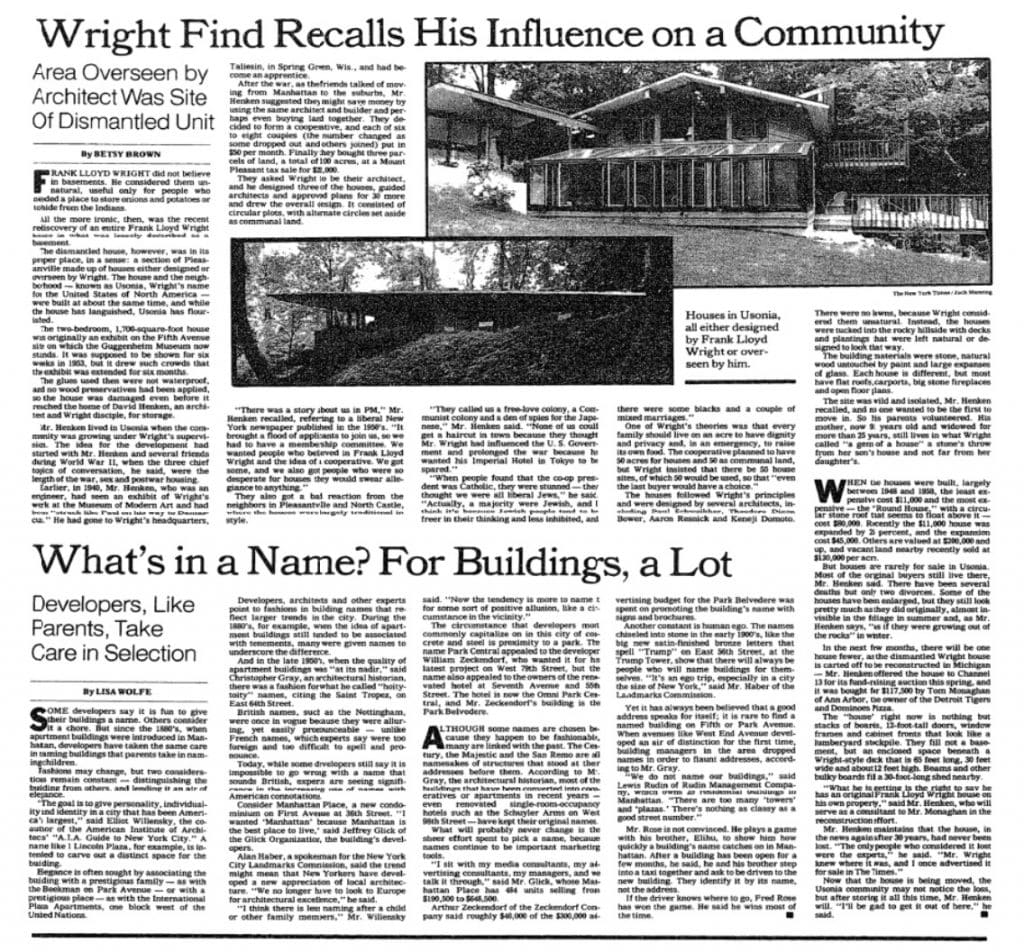

Pleasantville, Westchester County, New York, was one of three co-operative Usonian communities founded in the late 1940s. The other two, The Acres (also known as Galesburg Country Homes) and Parkwyn Village were both near Kalamazoo, Michigan. They all involved Frank Lloyd Wright as the overall site planner and in each case he designed the lots to be circular in form. The circles met with enthusiasm from the co-op members, but their unorthodoxy was to prove a bugbear to bureaucracy.

Westchester County Uses Circular Lots’, New York Herald Tribune, Oct 10, 1948.

‘No one would expect from Mr Wright anything in the ordinary as housing developments go. An iconoclast whose prejudices have been fully ventilated […] Instead of a conventional subdivision Mr Wright has elected to use a series of circular tracts each one... Continue Reading

Westchester County Uses Circular Lots’, New York Herald Tribune, Oct 10, 1948.

‘No one would expect from Mr Wright anything in the ordinary as housing developments go. An iconoclast whose prejudices have been fully ventilated […] Instead of a conventional subdivision Mr Wright has elected to use a series of circular tracts each one acre in size. On paper they satisfy, and who sees property lines in this sort of development? The tedious legal descriptions of property by metes [sic] and bounds are reduced to one point and a radius… It is the antithesis of conventional land ownership, which Mr Wright abhors. It reduces private ownership to a perfunctory formality, and should provide a litmus paper test of the co-operators intentions…’

‘Hand in hand with the radical architecture was the commitment to cooperative living. All the homes and land were owned by the Usonia cooperative,... Continue Reading

‘Hand in hand with the radical architecture was the commitment to cooperative living. All the homes and land were owned by the Usonia cooperative, and the first five homes were built with the group’s money. But in 1949, when the cooperative tried to get a mortgage on the first five homes in order to build the next five, the group of young professionals was rebuffed by one financial institution after another – cooperative ownership was a radical concept to the banks, and they refused to invest their mortgage money in the venture […].’

The fight to tame the circles was noted in the description of Pleasantville for The National Register of Historic Places in July 2012, together with the fact that the alteration to rectangular plots demanded by the Knickerbocker Federal Savings and Loan Association had been cheerfully ignored. Polygons or ‘hexed circles’ were the compromise solution.

... Continue ReadingThe fight to tame the circles was noted in the description of Pleasantville for The National Register of Historic Places in July 2012, together with the fact that the alteration to rectangular plots demanded by the Knickerbocker Federal Savings and Loan Association had been cheerfully ignored. Polygons or ‘hexed circles’ were the compromise solution.

‘As originally laid out by Wright in 1947, Usonia had fifty-five circular building sites, each one acre in size, or 200’ in diameter. Lots were arranged in clusters of six that surrounded common land, and some circles were part of multiple clusters. Because Wright originally aligned his circles in uneven rows, the spaces between the circles (or the building lots) were triangular in shape. Wright intended that these spaces remain undeveloped and serve as communal land. After the community reviewed Wright’s initial plan, it was slightly revised by David Henken and Aaron Resnick, with Wright’s approval, to eliminate several undesirable building lots and better align the roads with the topography. The revised plan had fifty, slightly larger lots, each 217’ in diameter. Several years later, after the community had begun to build, the cooperative secured a mortgage. In order to appease bank surveyors, Henken and Resnick modified the lots as polygons. Although this change affected the plan on paper, it did not change the layout or appearance of the community in any way, as owners continued to build within the circular building sites and maintain the uncleared land between in common.

In 1955, the plan was revised again when the community transferred building lots from cooperative to private ownership. At this time, many of the original triangular-shaped parcels between lots were incorporated into individual parcels. Again, however, this change was not observable in the physical fabric of the community, which continued to maintain the circular building sites. Today, the community consists of forty-seven residential lots, each exactly 1.25 acres, with one exception (the lot added in 1959 is 1.75 acres). They are distributed relatively evenly throughout the site. Property lines are blended together, due to the forbiddance of fences by the cooperative board and the prevalence of native plantings, and in most cases it is impossible to determine where one property ends and another begins. As Wright intended, each homeowner occupies a lot that is surrounded by vegetation and by other home sites, enjoying both individuality and community. Homeowners have generally planted low groundcovers (such as ivy or pachysandra), bushes and wildflowers, although several have small grassy lawns, and at least one has terraced plantings interspersed with sculpture. Several have in-ground pools, well screened from the community. The remaining forty acres of land, including the roads, are owned and maintained by the cooperative. The public land also includes a pool and tennis courts at the southern edge of the community and the remains of the stone pump house, the first structure completed on the site, which is missing its roof.’

(Quoted from the The National Register of Historic Places application.)

‘The colony has been designed by Frank Lloyd Wright of Wisconsin and Arizona, silver-haired exponent of “organic modernism”. Its features include round lots, solar... Continue Reading

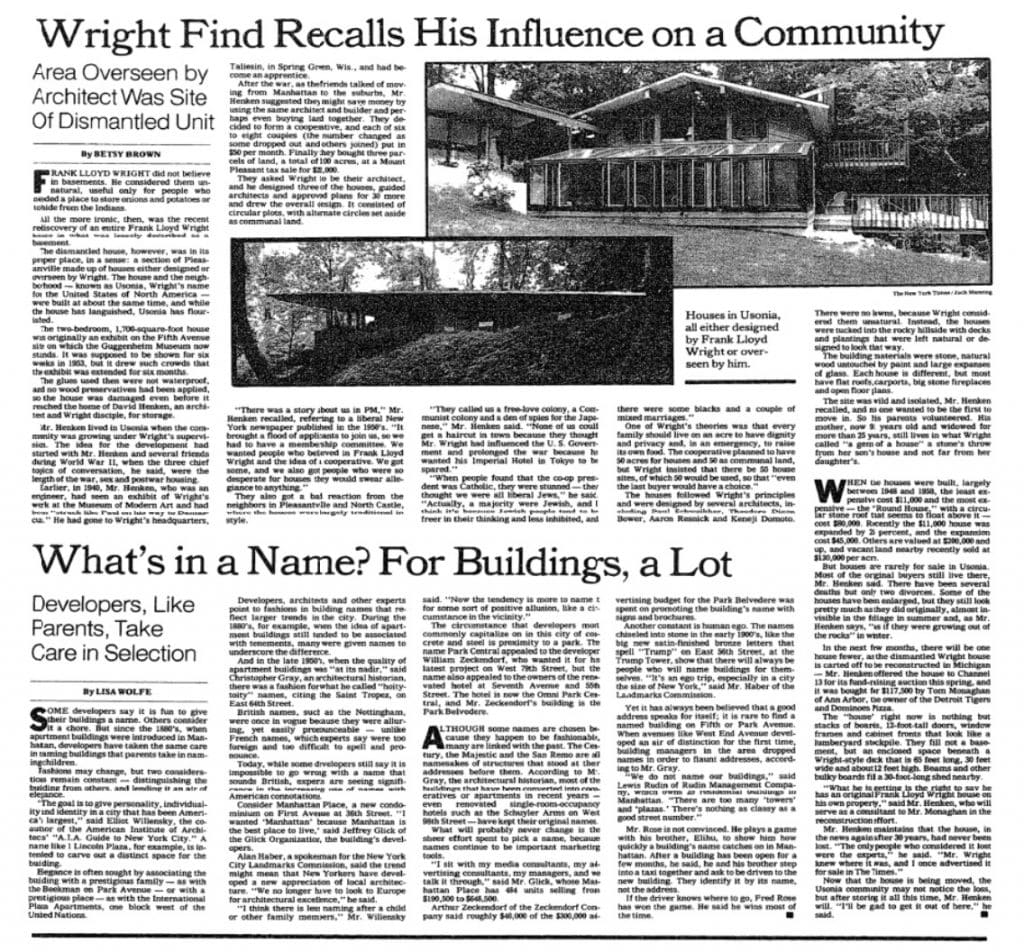

‘The colony has been designed by Frank Lloyd Wright of Wisconsin and Arizona, silver-haired exponent of “organic modernism”. Its features include round lots, solar houses, radiant heating, free-flowing interiors, wall-size fireplaces, cantilever roofs, extra broad terraces, spacious gardens and large expanses of glass….’

‘”[Our neighbours in Pleasantville and North Castle] called us a free-love colony, a Communist colony and a den of spies for the Japanese,” Mr.... Continue Reading

‘”[Our neighbours in Pleasantville and North Castle] called us a free-love colony, a Communist colony and a den of spies for the Japanese,” Mr. Henken said. “None of us could get a haircut in town because they thought Mr. Wright had influenced the U. S. Government and prolonged the war because he wanted his Imperial Hotel in Tokyo to be spared.”‘

‘One of Wright’s theories was that every family should live on an acre to have dignity and privacy and, in an emergency, to raise its own food. The cooperative planned to have 50 acres for houses and 50 as communal land, but Wright insisted that there be 55 house sites, of which 50 would be used, so that “even the last buyer would have a choice.”‘

Frank Lloyd Wright to Franklin D. Richards, Commissioner of the Federal Housing Administration, January 2 1950. Writing in regard to the plots at Parkwyn Village, Kalamazoo.

‘My dear Mr. Richards: seems to me you miss the point and ignore advantages to find imaginary obstacles. In the first place this is a community cooperative... Continue Reading

Frank Lloyd Wright to Franklin D. Richards, Commissioner of the Federal Housing Administration, January 2 1950. Writing in regard to the plots at Parkwyn Village, Kalamazoo.

‘My dear Mr. Richards: seems to me you miss the point and ignore advantages to find imaginary obstacles. In the first place this is a community cooperative project instead of the commercial real estate exploitation with which we are all too familiar. The individual plot knows no party lines, is easily located by one stake – the intervening space planted to native shrub requiring no care to develop an overall pattern among the buildings. Access from the public thoroughfare is entirely private to each lot as is the case anyway. “The market” is not the question as these young men are all intelligent home-owners likely to be superseded by others, if any, as intelligent.’