Alvar Aalto’s city

For whatever reason it is produced, a blueprint solidifies a moment in the design process and further solidifies the project. It is not necessarily the final moment, and often after the blueprints have been produced they might be annotated by one or the other master, resulting in new drawings from which new blueprints are produced, but the first blueprint marks the moment at which the design becomes realisable. The two blueprints shown here are of a design for a new administrative and cultural centre for Jyväskylä, and the moment they solidify is probably the best one in the long history of the project.

Jyväskylä is Alvar Aalto’s city. It is where he grew up, where he returned to open his professional practice after completing his studies in Helsinki, and although he soon moved further – to the top of the world – he returned with fanfares in 1951 when he won the competition for the new university, which was to be built next to the city centre, on a hill at the end of the neo-classical gridded plan of the city. Other projects followed: not much later Aalto completed designs for a new town hall for the neighbouring municipality Säynätsalo, and his own summer place close by. The university project turned into a series of commissions that he, and later his disciples, would continue to design as the campus grew along the lines of the original competition entry. In 1957 he designed a regional museum for the city (next to which he would before his death design a museum dedicated to himself), and in 1964 the city commissioned him to design a new administrative and cultural centre.

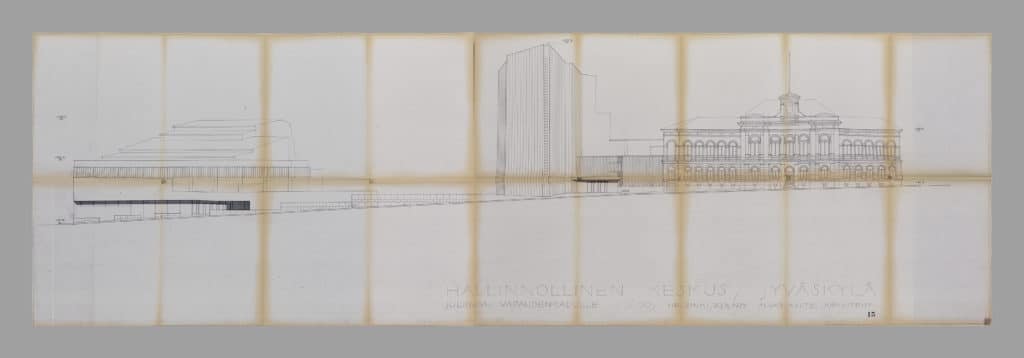

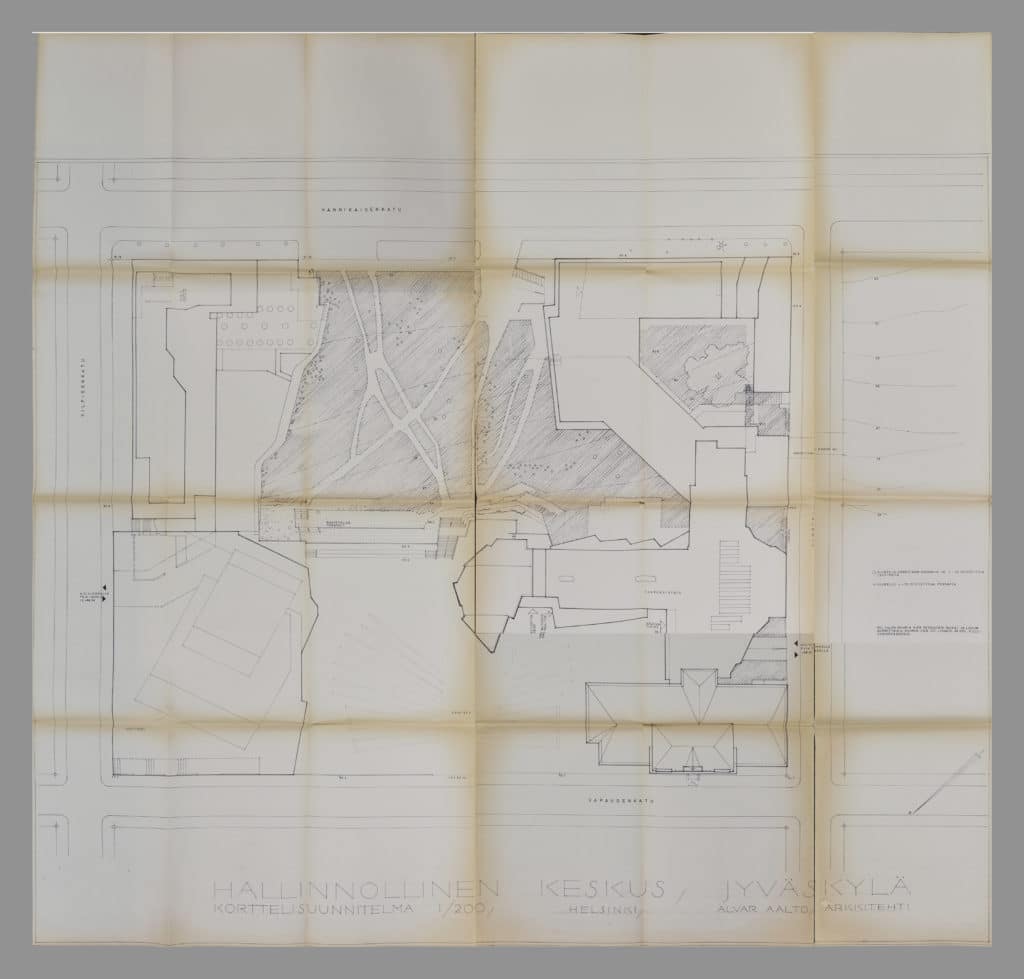

The project, like most such projects, saw many iterations and lasted for several decades. The present drawings show a version from 1972. The police building (poliisitalo) seen in the upper left corner of the plan had been completed in 1970, while the office building on the upper right corner of the site was to be completed in 1978, largely following what is proposed here in plan. The theatre (teatteri), in the lower left corner of the plan and on the left in the elevation, went through several iterations through the 1960s and can here be seen in the form it was built ten years later. The central element of the ensemble, the new city hall (kaupungintalo) with its assembly hall placed in a tower, proposed to be covered with dark granite, was never built and a car park remains on the site. [1]

These are huge blueprints, the elevation spanning close to two meters in width. Indeed they are so large that photographing them is difficult, and in order to reproduce them here they have been photographed in sections and re-stitched together on the computer screen, as if they had already cracked and broken into pieces, as they inevitably will one day: they are fragile and after lying decades somewhere folded and forgotten almost impossible to handle without breakage. But that’s how blueprints are. As with any blueprints, they were produced by the office in Helsinki, then handed to a city official, a contractor or a consultant, to observe the project. Whoever it was, the blueprints would stay with them for decades before being sold. It was someone who was to work on the site for some time, because they were kept together with blueprints from several years later. This someone perhaps liked the tower too, having kept the older blueprints, a past moment of the project where the tower still governs the picture. Rising above the the silhouette of the theatre and the old city hall, the tower accentuates the design and gives the whole project its character. It plays the leading role in the landscape, competing with the church tower across the street and framing the view from the church park (from which point the elevation shows the design), towards the lake glimmering not far off on the other side of the site. Since the tower was never built the present blueprints might be as close to the solid building as one can ever get, or at least as close as anyone would want to.

Editors Note: ‘blueprint’ remains a widely known term for prints of technical drawings by architects and engineers. A mid-nineteenth century invention, the blueprint process introduced a rapid and accurate method for reproducing the drawings needed by the construction industry. The Aalto prints shown here employ a later printing technique and are technically speaking ‘cyanotypes’. With thanks to Neil Bingham.