Hybrid Studio

Describing how architects work, Liz Diller noted that in her office ‘we draw, we look in each other’s eyes, we argue, we throw things around the room, we make models and break them apart, and somehow stuff gets made.’ However, things suddenly changed in March 2020. It became ‘very sanitized… we’re sending each other drawings and sketches; we’re responding through digital means and then having virtual meetings. Communication is slower.’ [1]

The coronavirus pandemic also radically changed how work was done in schools of architecture. A third-year undergraduate design studio in the Spring semester of the 2019/2020 academic year at the University at Buffalo, began on 27 January 2020. At 9AM a team of six faculty outlined plans for the fifteen week-long session to more than seventy students before each of the six studios met with their instructor. In our assigned space – a generous day-lit room in Crosby Hall on UB’s Main Street Campus – twelve students each chose a workplace. The room also had spaces where everyone in the studio could meet around a table, large models built and drawings pinned up for informal reviews.

The focus for this studio was the design of a Resilience Hub – a community centre to serve residents of an existing neighbourhood in Buffalo that could also provide a refuge for those people during emergencies.

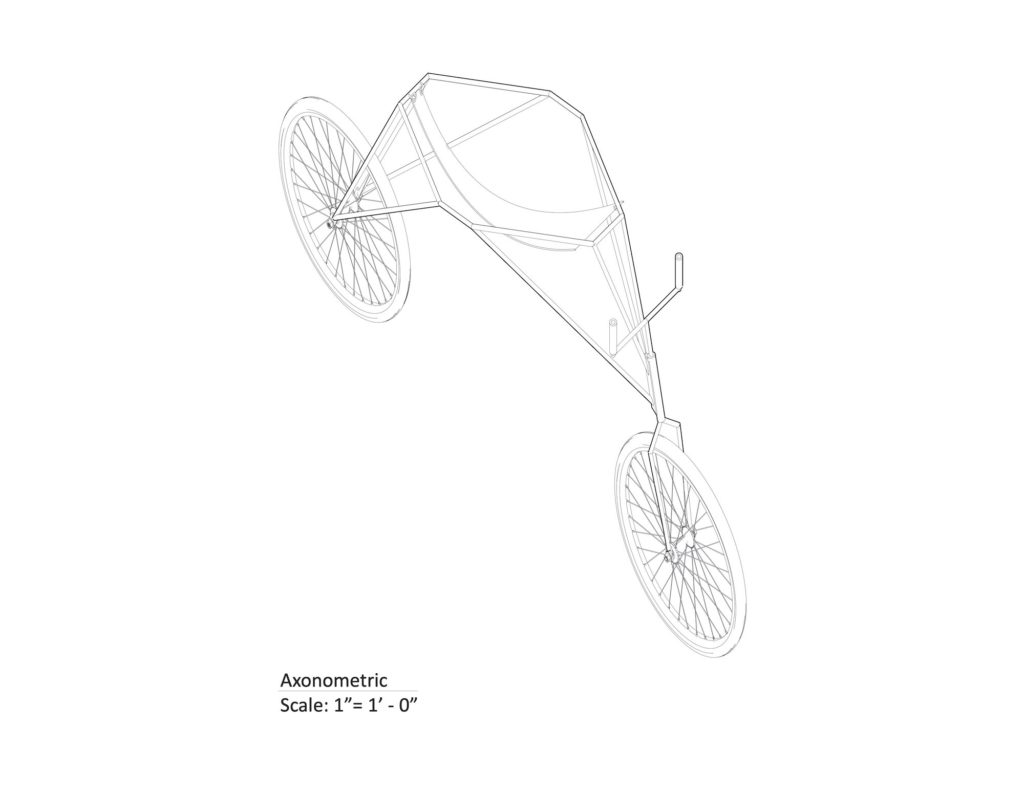

An introductory exercise focused on the ‘laufmaschine’ – a precursor of the bicycle and consequence of climate change brought about by the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815. That volcanic eruption, the largest in recorded history, caused prolonged disruption globally. Harvests failed, livestock died, food was scarce and epidemics raged in Asia and Europe. 1816 became known as ‘the year without a summer’ in the northern hemisphere and in June there were snowfalls in New York State. By explaining this event and its consequences to students the teaching team sought to highlight details and the significance of history while referencing the impact of climate change on people and design.

This first project required each student to design a ‘laufmaschine.’ Individual ideas, drawings and models were subsequently reviewed by everyone in the studio, common threads identified, and small groups of students clustered around different concepts. Each group was asked to develop ideas and build a full-size working ‘laufmaschine.’ Using the school’s workshop – a well-equipped facility where steel, wood and digital fabrication tools are readily available to all – students refined ideas and went to work. Each team was also asked to produce a four-minute video documenting the design, construction and testing of their machine and create team t-shirts. On 10 February 2020 – a bright but chilly morning – ‘laufmaschines’ from all six studios were tested with an outdoor run of almost two miles.

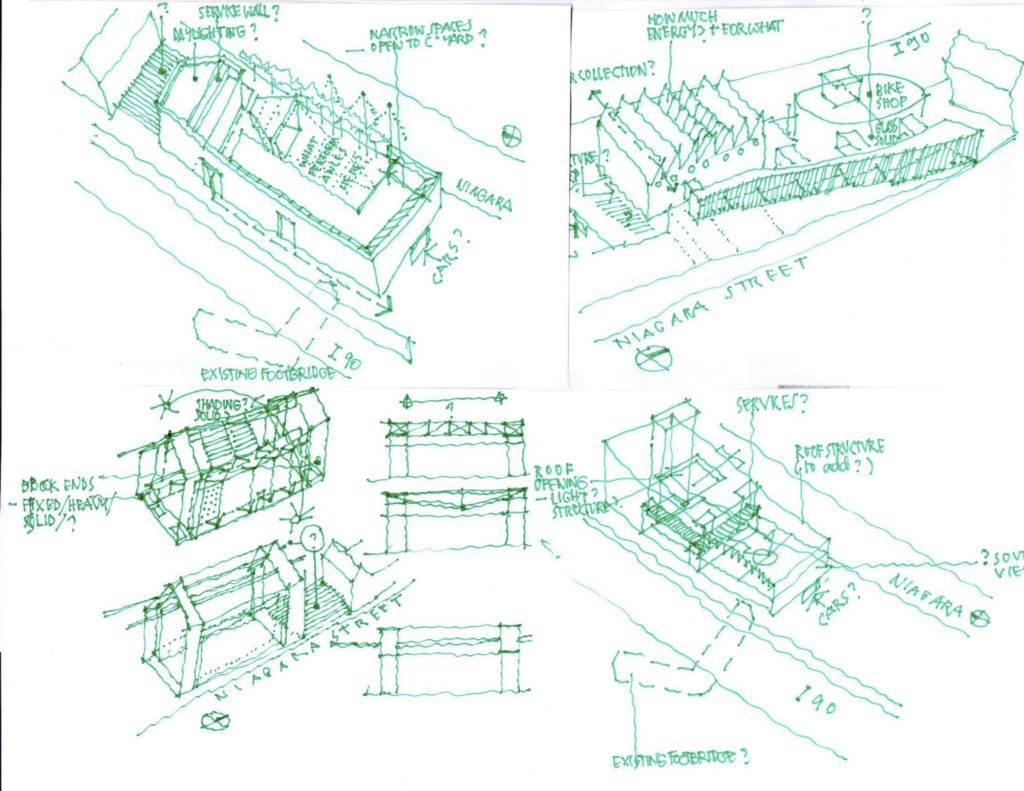

Students went on to visit the site for the new Resilience Hub. Located within the existing neighbourhood of Black Rock in northwest Buffalo, it is bounded by an existing Interstate highway, Niagara Street and a public bicycle path that connects to a well-used state-wide network. Close to the Niagara River, the site is signalled by a large swing bridge that carries the international rail line connecting the USA and Canada.

The brief for the 1417 sq.m. building outlined requirements for childcare facilities, a bicycle workshop and education centre, a coffee shop, administrative offices, an auditorium and a basketball court with changing areas and an exercise room. Students in the class were also asked to develop their proposals by demonstrating how the building could be used in an emergency.

This second assignment was scheduled for the remainder of the semester with interim reviews in February and March. Students were required to develop comprehensive design proposals that, in addition to programmed uses, addressed sustainability, servicing, materials, structure and construction. Consequently, additional reviews with technical specialists were planned in April. Final presentations and reviews with guests and visiting critics were scheduled for 8 May 2020. Throughout the semester the studio met on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays from 9AM–12.30PM. Sessions began with a brief studio meeting followed by 15–18-minute-long reviews with each student. Work in studio during the first half of the semester echoed those pre-pandemic activities described by Liz Diller.

With the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in New York State in March, the campus emptied and as everyone moved out of studio students and faculty returned home and to their families. All subsequent studios for the semester were conducted online.

Having worked directly with students in the studio for the first half of the semester, the sudden enforced separation was a major disruption that demanded radical adjustments immediately in readiness for classes to restart on Monday 23 March 2020. Online studios were organised, the same weekly timetable maintained, and all subsequent classes taught remotely.

Online studio sessions highlighted individual students, framed precisely and with each isolated in his or her own private room. A close-up face view was their new presence. However, students were encouraged to ‘meet’ together online for each studio session, and reviews with individuals were made fully accessible to everyone. This differed from the conventional studio and, as a consequence, work became public and individual discussions were replaced by group tutorials.

News of the developing pandemic, its impact in New York City and movement across the State, predominated. Students were anxious and some, and their families, were directly impacted by COVID-19. The relevance and design of a Resilience Hub became increasingly vivid.

Early considerations of the Resilience Hub focused on the design of spaces where people could gather for safety in an emergency. However, the pandemic introduced different demands, and as students learned of responses to building needs elsewhere so they reconsidered their own ideas regarding resilience, re-examined plans and formulated how to respond to new demands.

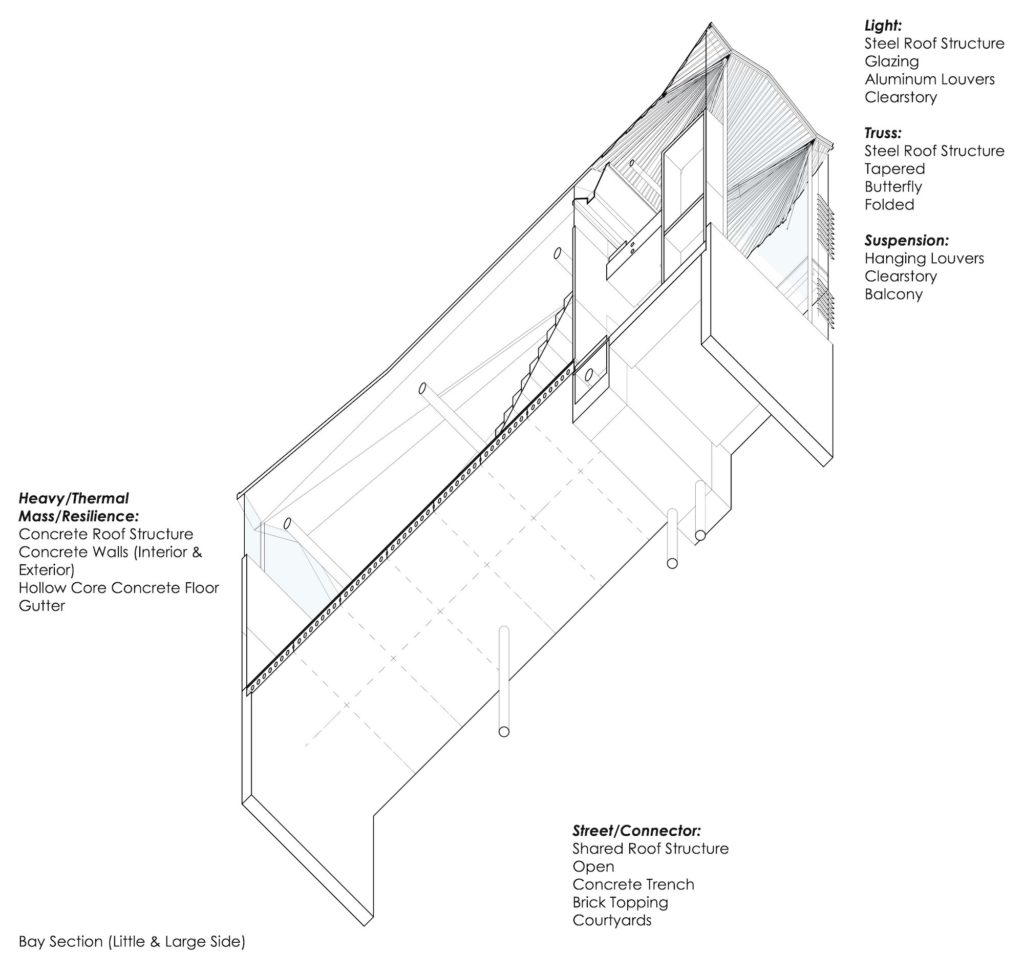

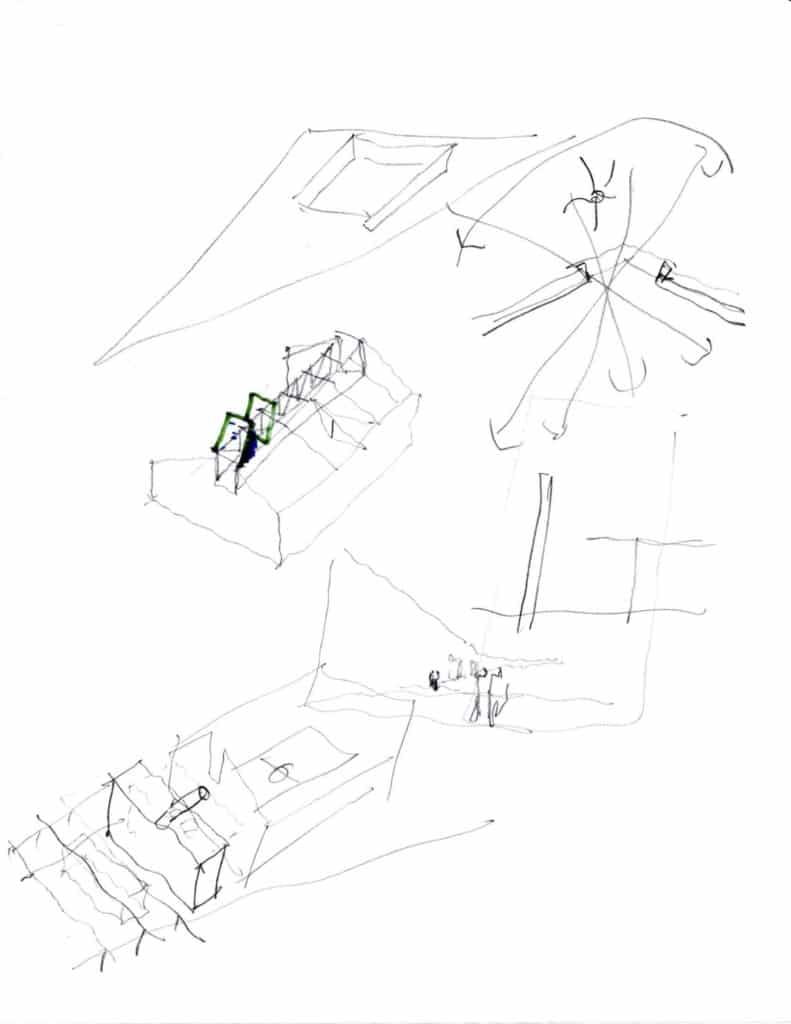

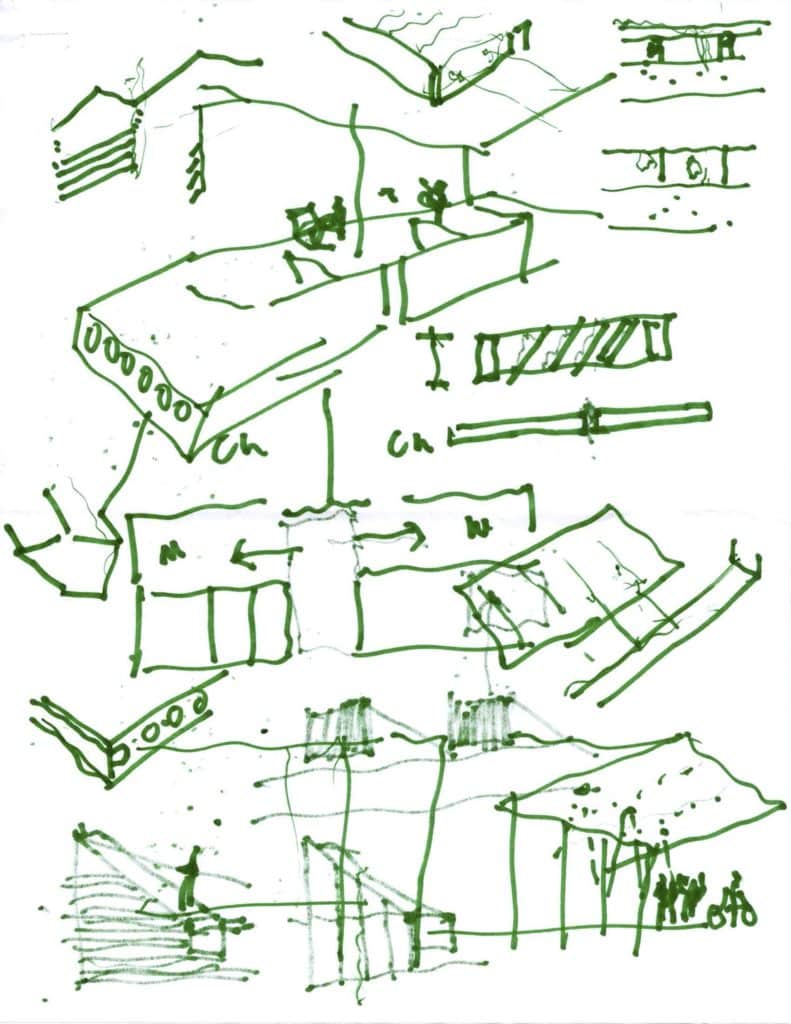

Throughout the second half of the semester our online studio did not utilise a ‘chat’ column and no digital tools were used to mark-up drawings remotely. Instead all students in the studio were encouraged to participate in live conversations and draw spontaneously to explain their design intentions and priorities. Faculty also drew. Sketches and diagrams were developed and annotated prior to being projected across the studio via laptop cameras and onto screens. This process was repeated during all online sessions and designs developed through conversations and shared iterative design studies.

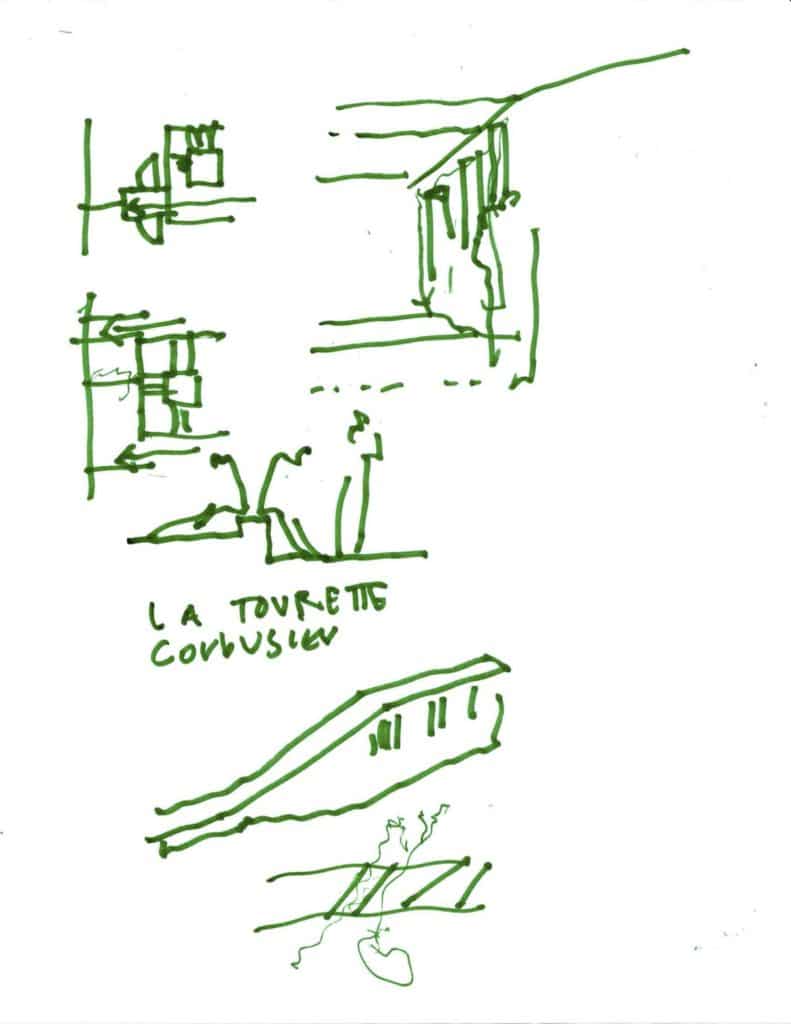

Drawing and drawings took on particular significance. Realising that a drawing was often worth at least a thousand words, students responded enthusiastically. They also realised that if online discussions were to be rewarding then drawings had to be clear, legible and comprehensive. They experimented and drew thoughtfully. Faculty joined in and ideas about siting, building organisation, access, materials, details of environmental, structural and construction systems and the coordination of building elements were assessed together. Drawings varied, but the use of sketch perspectives to advance design ideas introduced early in the semester developed a new momentum online. In the absence of physical models these drawings, together with axonometrics, were used to examine and explain design ideas, spaces and details.

In order to cultivate the sense of community within our online studio, faculty prepared brief notes periodically after conversations and reviews. In a traditional studio setting these comments would likely have remained with each student following conversations over their work. However, the notes were circulated to everyone in the studio and this ensured that references, precedents, suggestions and observations were confirmed for all. From time to time notes were supplemented with sketches and diagrams. These were also circulated to everyone. By making conversations and notes ‘public’ design awareness was hopefully enhanced for all. It also helped to create a sense of community amongst students who had formerly worked together in studio but were suddenly isolated and remote from one another.

Drawings by significant architects were frequently cited as references. Suggestions regarding specific drawings – by Le Corbusier, Diller Scofidio, Cedric Price, LTL, Siza, Ando, Wes Jones, Foster, Stirling and many others – were instantly ‘searched’ online and viewed on individual laptop screens that enabled everyone in the studio to see. Albeit students were scattered in different locations, the drawings were discussed and studied online by all simultaneously. This was also helpful as students began preparing to make their own drawings in this second stage of the studio, considered how to create ‘atmospheres’ and present ideas embedded in their own proposals for imminent final reviews.

In traditional studio settings students generate considerable energy as they prepare for these final reviews. Throughout the semester, and especially at these times, wanderings through the school and from studio to studio not only offer exercise, a change of scene and chats with friends but also provide inspiration and ideas. [2] Students remarked that such informal ‘grazing’ is invaluable – though hardly viable online!

Beautiful drawings, carefully organised displays, detailed physical models, outfits and verbal presentations of ideas are all important aspects of architectural education and much-loved features of final reviews in schools of architecture. These aspects of architectural education also permeate professional practice. The online studio was not conducive to theatre and spectacle!

The absence of physical models in our online studio was a major setback. At UB it is especially frustrating as materiality and making are fundamental to the pedagogy of the Architecture Program. In the first half of the semester students in each studio worked together to build large site models for the Resilience Hub project to help them study context, siting and building massing. However, with the closure of the campus these models had to be abandoned.

Some students experimented with simple models while working online. However, their impact was marginal. Others developed 3D models digitally but individual resources and limited access to hardware and software restricted their potential. As part of the final submission each student was asked to prepare a 4–5-minute video of their proposal. This was extremely helpful as it required designers to visualize their work broadly and to consider movement and context, the impact of weather and significance of details – considerations that are essential parts of architecture yet often elusive. Such exercises could usefully be encouraged in future.

The development of physical models in design is invaluable and the inability to explore design by building actual models poses particular problems in the online studio. Options for physical models that develop design ideas in online studios need to be reviewed.

Online studios proved to be helpful with regard to technical consultations and design reviews. They enabled sustained access to notable technical advisors hardly possible in a traditional studio setting. They also provided students with opportunities to ‘meet’ with specialists from across the country and create valuable links with distinguished critics and practitioners who participated in online reviews.

In this context, the online studio has the potential to create new alignments with professional practice. While Liz Diller espouses the studio as a place for work in her own practice, other architects adopt different approaches. For example, a colleague recently described how architects working in a large corporate practice had engaged with clients, fully designed and overseen the construction of several large complex buildings overseas without ever leaving their office in North America. Such ways of working are increasingly common in contemporary architectural practice and developing skills in online studios that enable students to participate actively yet remotely is valuable.

Plans for design studios in the upcoming semester of the 2020/21 academic year are currently being formulated. Ongoing disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic are shaping those plans. However, the hybrid studio taught in Spring 2020, albeit enforced and sudden, offers important lessons that will be invaluable in advancing new contemporary formats for the education of students as well as the practice of architecture.

Notes

- Liz Diller, ‘Practicing Architecture in a Pandemic’, Robin Pogrebin, New York Times, May 29, 2020. Page C1.

- Nicholas Adams, Bunshaft and SOM – Building Corporate Modernism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 14. Describing Gordon Bunshaft wandering through the studios at MIT when a student a colleague notes – ‘Gordon was the kind of guy that would walk around and look at everybody else’s scheme’

– Fabrizio Gallanti