OMA: Collaborators—Allies

This is the fifth post, in a series of six, titled OMA CONVERSATIONS. The series is the result of a collaboration between Drawing Matter and architect Richard Hall who, over the past two years, has conducted twenty-three in-depth conversations with key collaborators working with OMA during its formative years. Drawing Matter has long had an interest in the work of OMA in this period, in particular the role of Rem Koolhaas in establishing the model of a horizontal organizational structure and the purpose, and techniques, of drawing in its distinctive repertoire.

COLLABORATORS—ALLIES draws from conversations with Hans Werlemann, Claudi Cornaz, Madelon Vrisendorp, Zoe Zenghelis, Vincent de Rijk and Frans Parthesius all working across time and place on several projects.

Upcoming, the sixth and final posts in the series is a concluding conversation with Rem Koolhaas on the challanges in becoming an Office. Find more about the project, including a list of all posts, here.

From the very beginning, OMA actively engaged non-architects in the design process. Initially through the immediate collaboration with painters Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesendorp, as well as critics such as Charles Jencks and Kenneth Frampton. Later, in Rotterdam, the encounter via Kees Christiaanse with artists at the ‘Utopia’ collective (including Hans Werlemann and Claudi Cornaz) and the grooming of industrial designers as modelmakers (Frans Parthesius and Vincent de Rijk), led to the establishment of a solar system of third-party contributors orbiting the office.[1]

OMA developed long-term relationships with this extended family (later including the engineer Cecil Balmond, designer Petra Blaisse and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, amongst others), who had a significant impact on both the output of OMA and the development of the individual contributors.

The following extracts are from conversations with significant third-party collaborators in the fields of representation and communication during OMA’s formative phases.

Notes

- The ‘Utopia’ collective was squatting in an abandonned waterworks in Rotterdam.

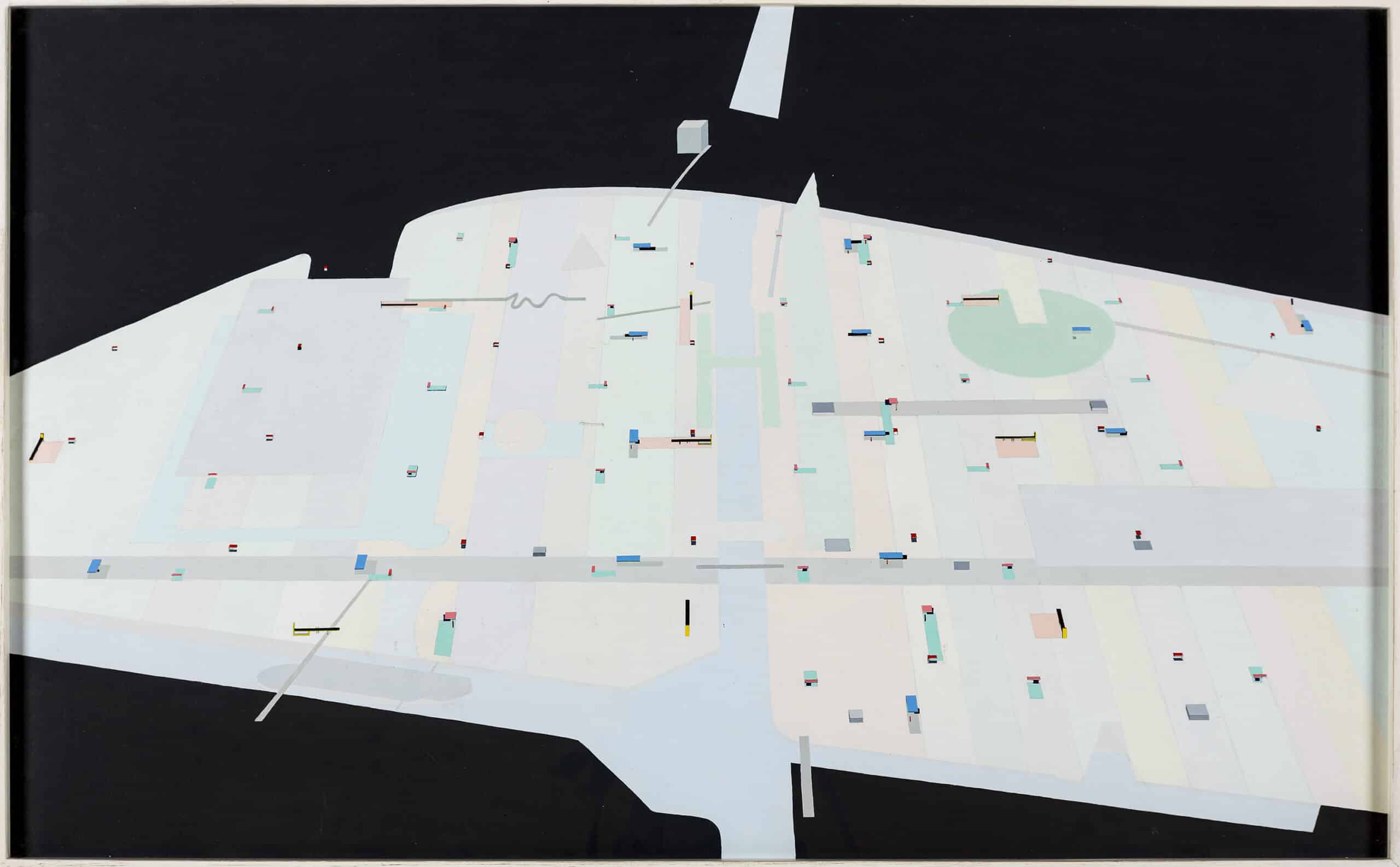

300 x 418 mm. DMC 3151.9.1.

‘With Rem and Elia, it was mostly (working) apart. They’re so different: the minimalist and the maximalist. But we all came together when there was a huge painting to be filled. We would get anybody to come and help: ‘Hey you, fill in that piece of blue’. But Rem and Elia always had their own scenes. Even for the Casabella competition, it was a strip and their had their own squares. You were doing the model.’ (MV)

‘Yes. On the glass.’ (ZZ)

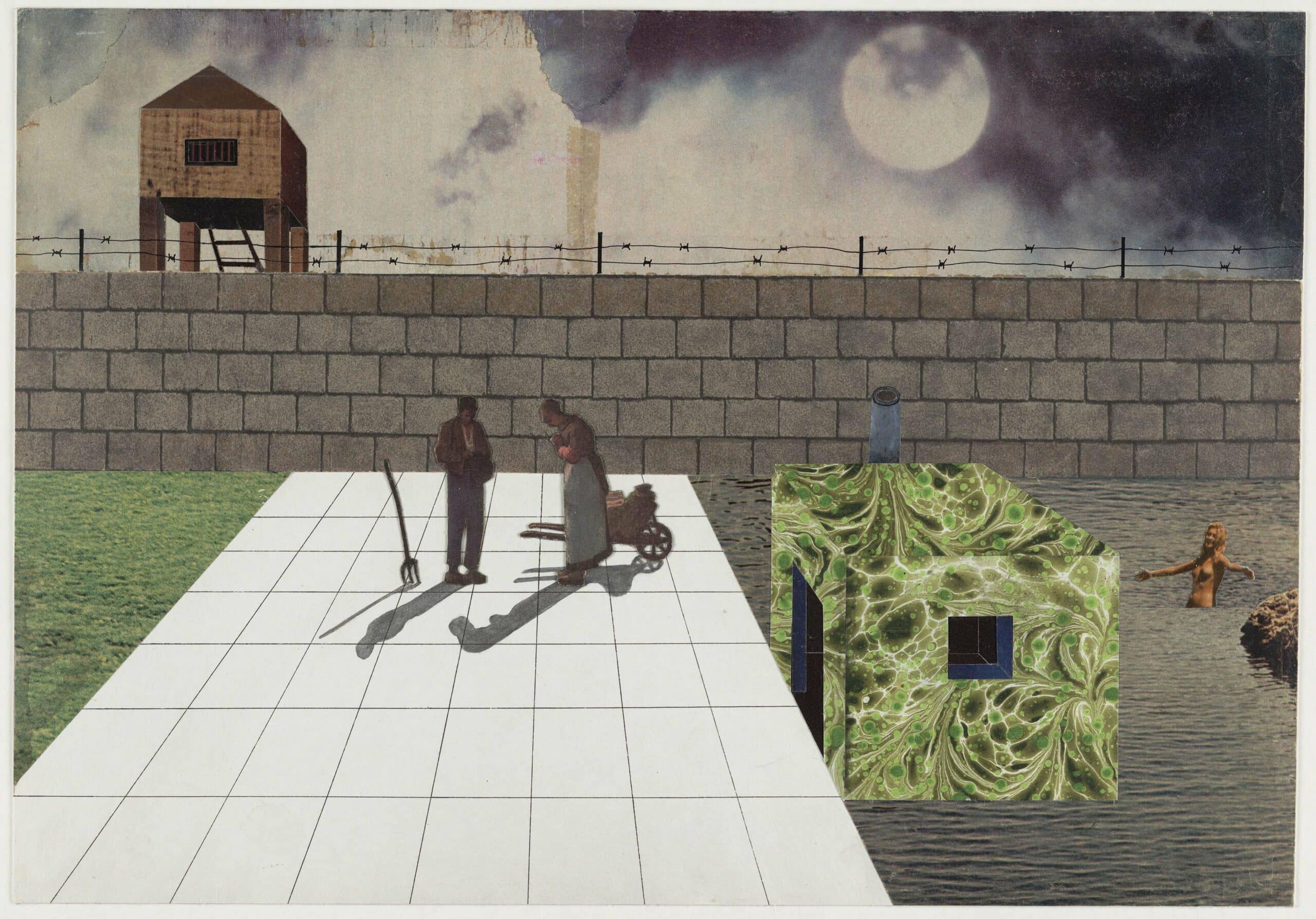

‘They did what they wanted. Except sometimes I was fighting like crazy! Not to put a naked woman in the collage. ‘No, let’s not do that’. It was for the collage about the allotments [in Exodus]. Rem wanted this naked woman in the water, and I said, ‘Why does she have to be naked? Leave her out’. It was to be added to the image with the man and woman praying… you know, the farm?’ (MV)

‘Oh, yes. We did so many (versions). We were constantly trying things out, so we made many versions. Someone would say, ‘Oh perhaps this should be a night image’, so we made a night version.’ (ZZ)

‘But also, somebody said, ‘Can you make another one?’. That’s how the French painters did it: someone would say, ‘Can you make that painting again?’ They did hundreds of copies of the same painting.’ (MV)

‘Yes. It was also the demand from outside. Not only us—mostly we did versions when we wanted to try something else for the same image—but many times, the very popular ones went straight away. So, we had to make more of them for us.’ (ZZ)

‘Working for OMA as a pleasant and inspiring time. There was the feeling that something new was introduced to architectural thought. There was undeniable optimism, magical storytelling and inspirational drawings and paintings. I think that OMA inspired and influenced many students and young architects—sometimes for the best.’ (ZZ)

— Madelon Vrisendorp and Zoe Zenghelis Transcript click here.

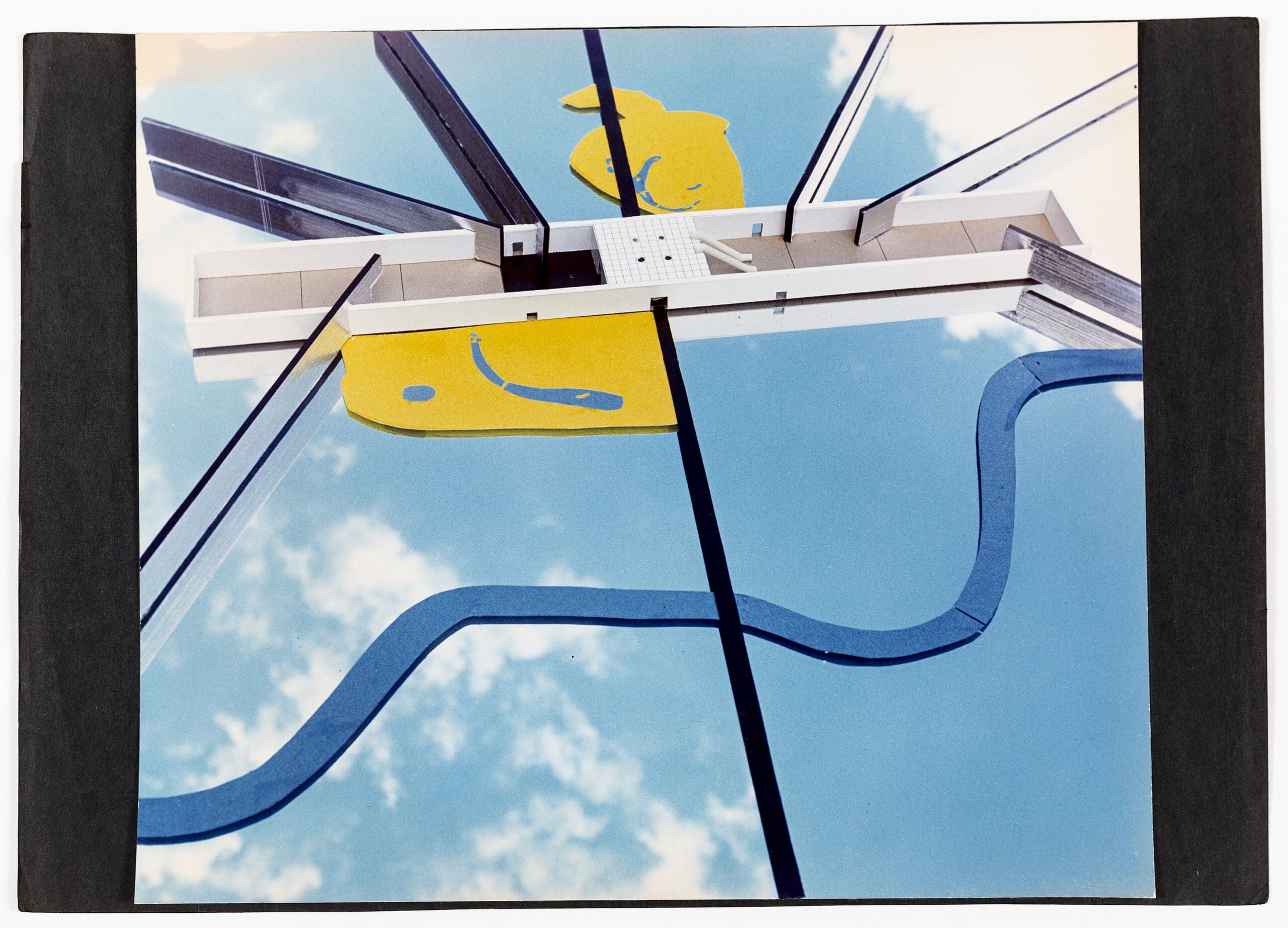

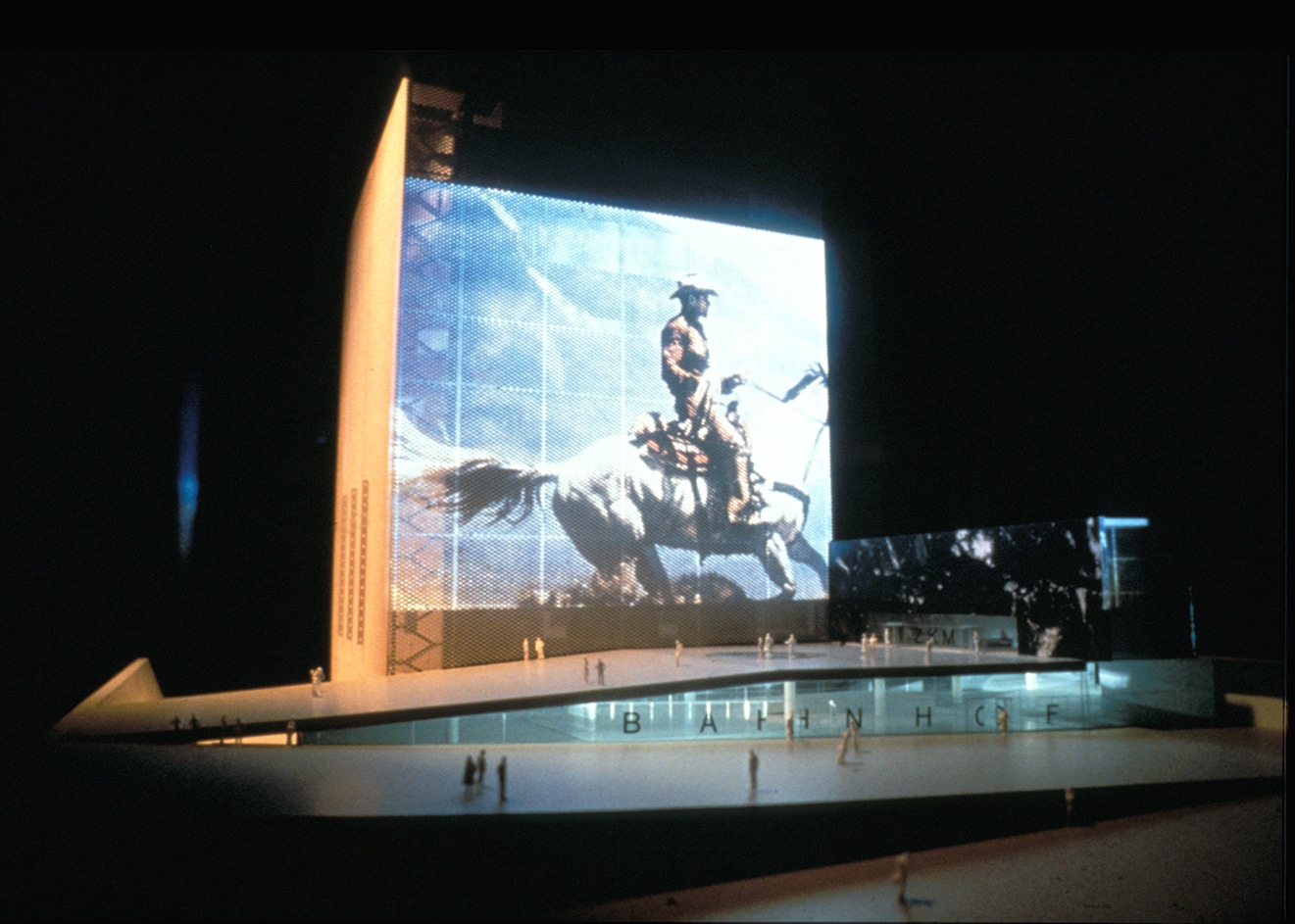

‘Nothing was standard. We were there for days and nights. We worked all the time because it was so nice to do. Rem has this strange habit of inspiring people. But he could really create tension too. He organised the office in teams and then—like a wasp—he went from team to team. He would come in the morning, divide his time across all these teams and then went running or swimming. Then, he came back at night while everybody was developing things. This is the machine that Claudi made for video projection.’ (HW)

‘For ZKM (Zentrum fur Kunst und Medientechnologie). We made a screen on the facade, to show images with as few pixels as possible.’ (CC)

‘Nowadays we have 5K. But this is so simple, with the same effect.’ (HW)

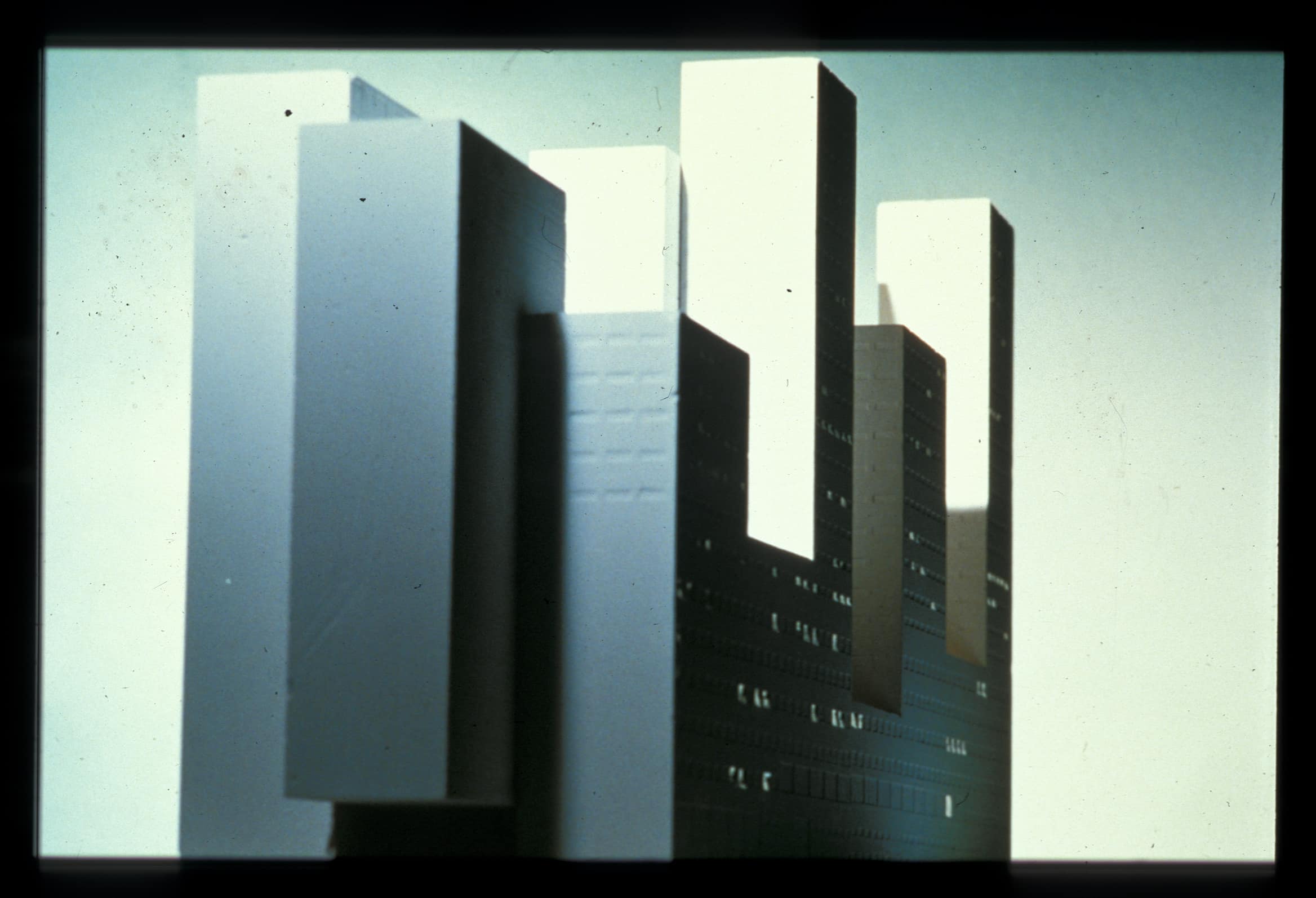

‘This was made with blocks of gypsum. All the windows were made with a hammer. The model is huge! Very heavy. We put aluminium foil in the windows for the photographs.’ (HW)

‘At OMA’s office, there was everything. For instance, Stefano de Martino sitting at a very big drawing board—with a cigarette holder, like an Italian gentleman—surrounded by thousands of coloured pencils, making images of the prison in Arnhem. Meanwhile, Claudi is skating through filming.

The time we are discussing was the analogue period. I think these skills are dying out. The kitchen here was a big darkroom. I could handle any paper or colour, with very quick results. Slides were the quickest, but I had so much to do it was easier to take them to a laboratory. We would stick the films on the wall and Rem would mark with a small sticker what he liked—and then I’d mark what I liked. That was part of his theory: he’d ask, ‘Which would you include?’—and he’d add them into his story. When he gave lectures, he’d have two-three carousels with slides in a plastic bag. In the other bag, credit card and sneakers. Off he went on the plane to do it.

The trick was to have no borders. Even on holidays, when I was in France camping somewhere, Rem could call me up, ‘Is it ok if you come to Rotterdam, we have to do a few projects?’. The next day, I went to Bordeaux and jumped on a plane. It felt normal.’ (HW)

‘It was really like a pressure cooker. There was so much going on at the same time. Everybody had enormous energy and wanted to do it. It wasn’t a formal process—it was an experiment—that was really important.’ (CC)

— Hans Werlemann and Claudi Cornaz Transcript click here.

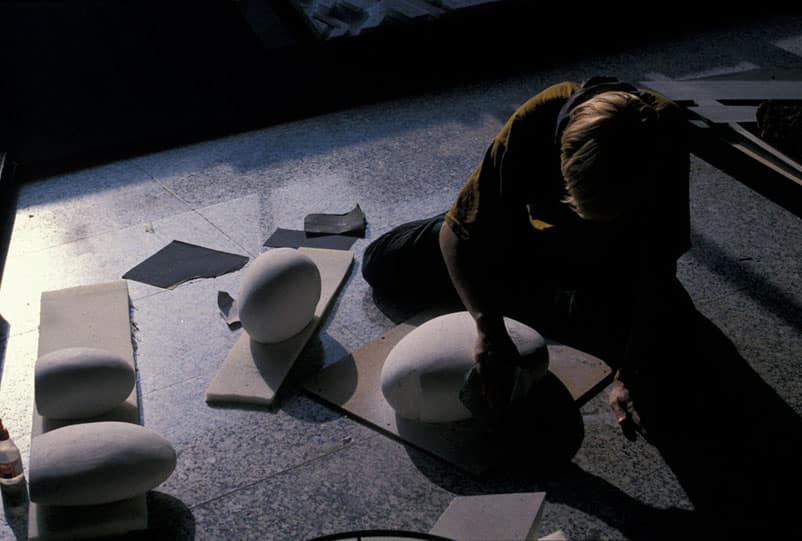

‘Well, by then (Très Grand Bibliothèque) we were starting to know the office, much more than was the case with the NAI. We shared the excitement about doing this. But it was also difficult. We didn’t know how the handle the office: we were going to do this, and it was really exciting—we had this meeting with everyone—and then we waited two weeks for the drawings. We really needed to do something, and at the same time Rem was asking, ‘What do you have?’! So, based on the conversations we just started making material studies and shape test. We put them all in a box and took them to the next meeting.’

That was really a special moment because we put these things on the table, and Rem looked at it. He grabbed something, jumped up and he ran away. We didn’t know what was going on, but the others ran after him. He went to the elevator, which had a light strip to one side, and he held this little piece of material in front of the light. We had just made these quick random shapes out of acrylic based on what we had seen in some drawings. There was one that was still kind of rough—the one he held in front of the light—which we saw worked for his idea.

Later on, we were in the workshop and the telephone rang—another of these weird telephone conversations—’Yeah, I’m in a gas station in France. So, what you need to do is make the voids. I only want to see the voids’. Clank! We didn’t even know there were any voids. But we knew the basic story: that it was just a grid of floors and walls and then it had all these big rooms in it, in weird shapes: reading rooms and so on. Those where his voids.

So, the idea only became visible as a model. I worked on it, but it was really Vincent’s idea, to make the big plaster models. One shows the block with the holes and the other shows the holes as volumes. It could all be cast as one thing. I mean, it’s really a piece of engineering. But only in that model is the concept really visible. I think the model we made originally for the competition was nice, but it was really a very classical model.’

— Frans Pathesius Transcript click here.

‘Then I thought, ‘Well ok, what if we do it in plaster?’. But Rem didn’t think it was a good idea. Then, he had this show come up in the Stedelijk Museum and he came back, ‘Now you can do the plaster model. I want to have it 1:100’! So, that’s a cubic metre. I had to prepare it really well: where the separations were; what was first; how all the inserts would work; and how the positive model and negative model would look together—because they’re meant to be seen together to communicate the concept.’

‘Then Rem said, ‘Ok, we can sell these things!’. He sold them to Centre Pompidou, MoMA and three or four other places. So, we had to keep making them. In fact, at MoMA, I made one there in New York. It was easy money. Rem sells it to the museum for quite a bit of money and every time he paid me 10,000 for it. For me, it was only three days of work, and hardly any material costs because I already had the formwork. So, it was a really good deal. It also compensated for all the other competition models that we made with no budget, taking many days and nights of work for something that we probably wouldn’t win!’

‘It’s also a consequence of time limits. Which were sometimes ridiculous. But at every level in the office. Rem does it on purpose almost! He never gives a decision a week before the deadline so that there’s time to calmly work it out. He’s always like, ‘Ok, what other options are there?’. When everything is put on the table, he asks what else is possible. He wants a process where there’s always room for unexpected things.

Once you know that, it’s easier navigate. I don’t need to worry about whether I have done the right thing, it’s just something I put on the table. I don’t need to care if it gets thrown away, it’s just there for the discussion. I don’t try to think what Rem thinks. It doesn’t work. Other people try to do that, in the office, ‘What will Rem think of that?’…but that’s not a good strategy! He’s always trying to go further, to do something unprecedented. In that way, I only try to make interpretations from what other people bring in: their concepts and ideas. I like it when those concepts are understandable, but it doesn’t have to be super-defined. If the idea is understandable, we can work together.’

— Vincent de Rijk Transcript click here.