Seven Facets of Architectural Disegno

The following text was first presented at the 2021 edition of the Lucerne Talks, the biennial Symposium on Pedagogy in Architecture at HSLU’s School of Engineering and Architecture in Lucerne; Drawing Matter’s Niall Hobhouse and Matt Page also took part, with their text Quantum Collecting. It was later published as part of Lucerne Talks: Drawing in Architecture Education and Research, ed. by Heike Biechteler, Dieter Dietz, Johannes Käferstein, and Jonathan Sergison (Zurich: Park Books, 2023), 28–38.

1. ‘Vo esere uno buono disegnatore e vo [di]ventare uno buono architettore.’

Reflecting on architectural education as a historian among architects presents a distinctive challenge. One feels the slightly uncomfortable impulse to justify the utility of the contribution: to avoid taking refuge in an outmoded Kunstwissenschaft, the only alternative seems to deliver a critical judgment, or in other words, a theory. I find neither extreme satisfying. I hope instead to situate my work somewhere in the uncharted middle. Rather than presenting a close analysis of disegno, either etymologically or historically, or a glossy, instrumentalised narrative of how architects used drawing in the Renaissance, this essay, like the talk it is based on, attempts to show the varied facets of the relationship between disegno and architecture. Its complexities and contradictions may come in this way more clearly into focus.

We know without doubt that architects in the early modern period drew, and that drawing became increasingly more integral to the practice of architectural design until by the mid to late sixteenth century no Italian architect considered his work possible without an active drawing practice.[1] This plain fact obscures many more ambiguities. At the simplest linguistic level, the word disegno could mean either ‘drawing’ or ‘design,’ sometimes both at once, and more rarely the innate ability to design well. Furthermore, the designation of ‘architect’ (architetto, architettore), as seen in a mid-fifteenth century workshop drawing by the Florentine goldsmith Maso Finiguerra, often meant ‘designer’ or ‘creator’ in a more holistic sense.[2] Within this ambiguity, nevertheless, drawing and architecture appeared together more and more frequently, when previously this had not been the case.

2. ‘Disegno, padre delle tre Arti nostre’

In the preface to the 1568 edition of the Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari described architecture, sculpture, and painting as the children of disegno.[3] His text expanded on the shorter preface of the 1551 edition, which contained much less theoretical content. In part this reflected the overall advancement of art theoretical writing in the intervening decades. In 1568, Vasari described the relationship between disegno and the arts as follows:

Because disegno, father of our three arts, architecture, sculpture, and painting, originating from the intellect, derives a universal judgment from many things, it is similar to a form or idea of all the things in nature, which is most remarkable in its extent […]. And because from this understanding there arises a certain conception and judgment, there forms in the mind something which, when afterwards articulated by the hand, is called disegno, we may therefore conclude that disegno is simply a visible expression and declaration of the concept in our minds and that which others have imagined and given form to in their idea. And perhaps from this arose the proverb of the Greeks, ‘from the claw the lion’ […].[4]

In Vasari’s framing, the arrangement appeared simple: drawing united all three forms of art and set them apart as a special group, higher than the other types of (merely decorative) design. The selection of painting, sculpture, and architecture as worthy media then generated the list of artists included in the Lives as ideal exemplars of those fields, and architects—who were generally, but not always, also painters or sculptors—apparently be longed as fully as the other two. For all three, the part generated the whole: disegno, in the mind as well as in the hand, held within it the entirety of the work. Today this idea no longer holds the possibility to surprise, as we are long used to believing, against all experience, that the drawing set more or less sufficiently conveys the architect’s ideas, or that a painter first makes a preparatory drawing. In the sixteenth century a similar conventionality had not yet taken hold. Vasari needed to assert that the idea of the project was its disegno, which was physicalised through drawing. This was true for a painting, for a building, or for a lion: if the disegno was a good one, it alone could generate the magnificent whole. Conversely, without disegno, the whole could not come into being.

3. ‘il principio e la fine di quell’arte’

Even for Vasari, however, the alliance of architecture, painting, and sculpture under disegno remained uneasy. For architecture in particular, he insisted that drawing belonged most properly to its practice:

All these [disegni], or profiles or whatever we want to call them, are as useful to architecture and sculpture as to painting. They are however chiefly useful to architecture, because its disegni are only composed of lines, which as far as the architect is concerned are the beginning and the end of his art, because all the rest, which is made by means of wooden models derived from those lines, is nothing other than the work of carvers and masons.[5]

When Vasari wrote, drawing as a design or primary recording tool for architecture had only recently entered common practice. Documentary evidence of experienced rather than theoretical building activity demonstrates that three dimensional models, detail templates, and verbal exchange between architects, patrons, and workers remained significant, if not often preferred.[6] Drawings circulated in this economy of representations, but in smaller, more partial ways: as reference images of ornamental details or complex lifting machines, or in contractual documents outlining the general particulars required by the patron. Vasari used drawings, as the carriers of the design or the idea of the work, to raise architecture indisputably to the abstract status that would move it outside of the less valorised artes mechanicae, and thus a profession worthy of the attention he lavished on it. In the process he distinguished the architect from the mere ‘carvers and masons’ with a sharpness not entirely reflective of real practice. His architectural disegno existed more clearly in texts than anywhere on the building site.

4. ‘sed certis ratisque dimensionibus annotari’

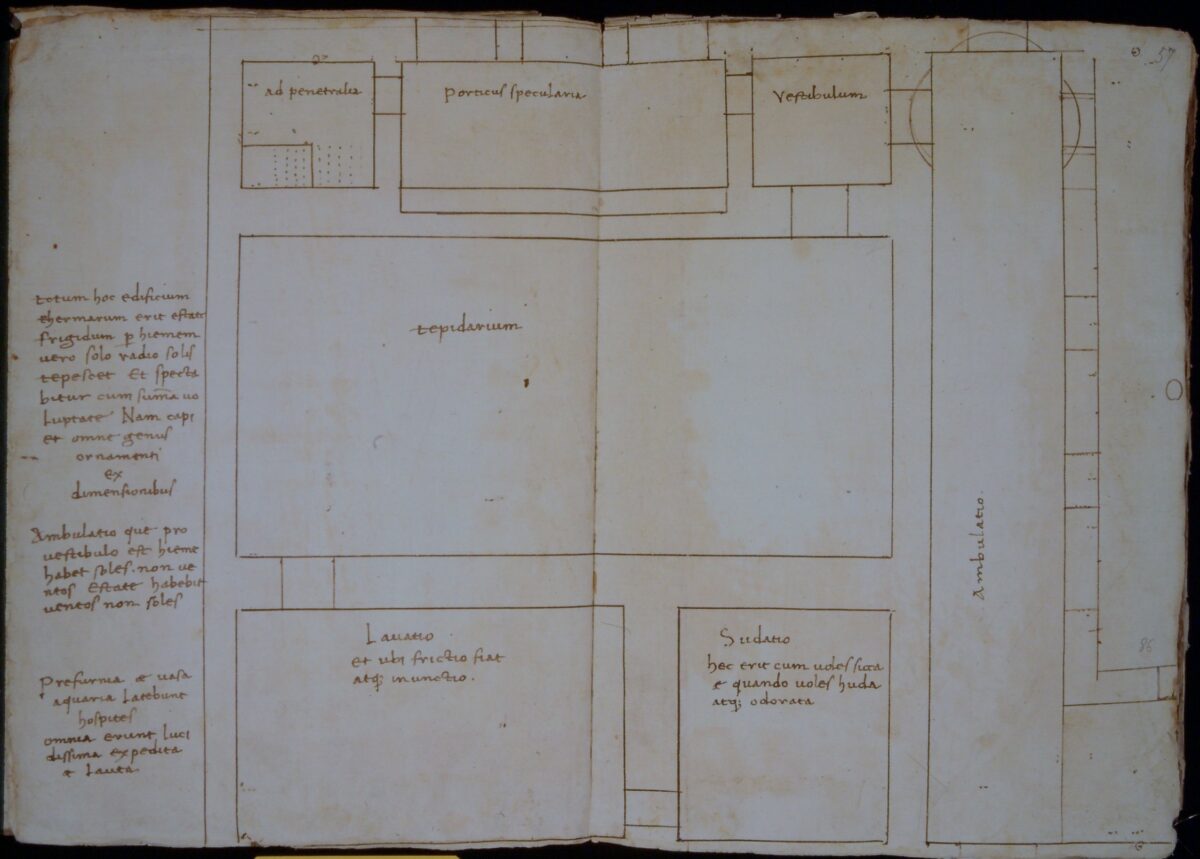

Well before Vasari, writers on architecture had exerted considerable effort on the proposition that architectural drawing possessed a rationality unique to its discipline. Already in the mid-fifteenth century, Leon Battista Alberti described the difference between how painters and architects drew; the latter ‘desire[d] his work to be judged not by deceptive appearances but according to certain calculated standards.’[7] Alberti outlined the basics of orthogonal plan and elevation as the architect’s correct procedure and seemingly dismissed other ways of working. Several decades later, Raphael and Baldassare Castiglione elaborated further:

And since the way of drawing most relevant to the architect is different from that of the painter, I shall say what I think opportune so that all the measurements can be understood and all the members of the buildings can be determined without error. The drawing of buildings relevant to the architect, then, is divided into three parts. The first part is the plan—the so-called flat drawing. The second is the ‘exterior wall,’ with its ornaments. The third is the ‘interior wall,’ also with its ornaments.[8]

By their period, the real-world practice of architecture utilised drawing much more then in Alberti’s day, and they thus spoke of orthogonal projection—plan, elevation, and interior section—in embodied graphic terms that evoked an active understanding of how to draw buildings for an architect’s needs. The specifically and exclusively architectural orthogonal drawing made it possible to claim both meanings of disegno for architecture: the disegno-design gave architecture an idea, while the disegno-drawing guaranteed a mathematical, error-free clarity for a field that might otherwise easily be considered dirty, dusty, and of questionable intellectual repute.

5. ‘il che non apar nel dissegno di quelli che son misurati architectichamente’

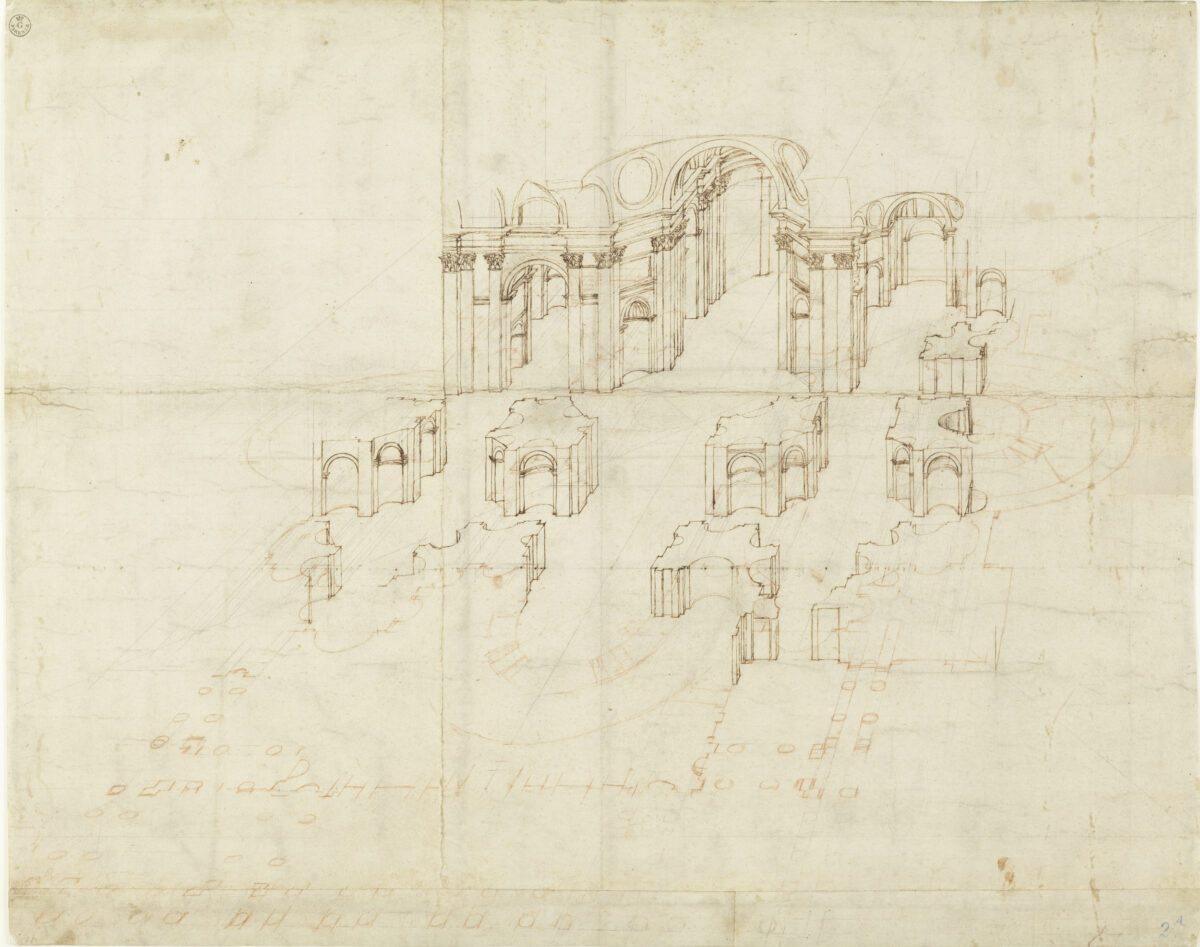

Orthogonal representation effectively spoke to rationality, with its Euclidean sense of space. Scholars and architects up to the present day have occasionally found that narrative so seductive that the complexity of its early modern application does not always receive full attention. Renaissance theorists them selves displayed considerable flexibility on the point. Alberti stated, ‘I will always commend the time-honoured custom, practiced by the best architects, of preparing not only drawings and sketches (pictura) but also models.’[9] Raphael and Castiglione similarly made room for other ways of seeing and drawing:

And in order to satisfy even more completely the desire of those who like to see and understand well all the things that are to be drawn, we have in addition […] drawn in perspective some buildings we thought lent themselves to it. We did this so as to enable the eye to see and judge the grace of that likeness, which is demonstrated by the beautiful proportion and symmetry of these buildings, and which does not appear in the drawing of buildings that are measured architecturally.[10]

Perspective drawings had their place, both in practice and in theory. In everyday use, architects utilised perspectives in ways that evoke contemporary renderings; they showed spatial relations and could convey a feeling of the proposed building in a more immediately visually comprehensible form than technical orthography permitted. For theoretical writers, the judgment of the eye represented it self a critical pathway to aesthetic quality. Later, Vasari would write of Michelangelo that his work succeeded because he had ‘compasses in his eyes’ and could thus make visually pleasing forms without recourse to exact measure.[11] Alberti had long before identified the design necessity of a plurality of representational strategies—and perspective very possibly was what he intended by pictura. Models crucially moved the disegno-design across dimensions, which he considered the most effective strategy for visualising weakness in the design. Neither flat drawing nor spatial model alone could completely incarnate the mind’s conception.

6. ‘fare varii disegni nella sua mente’

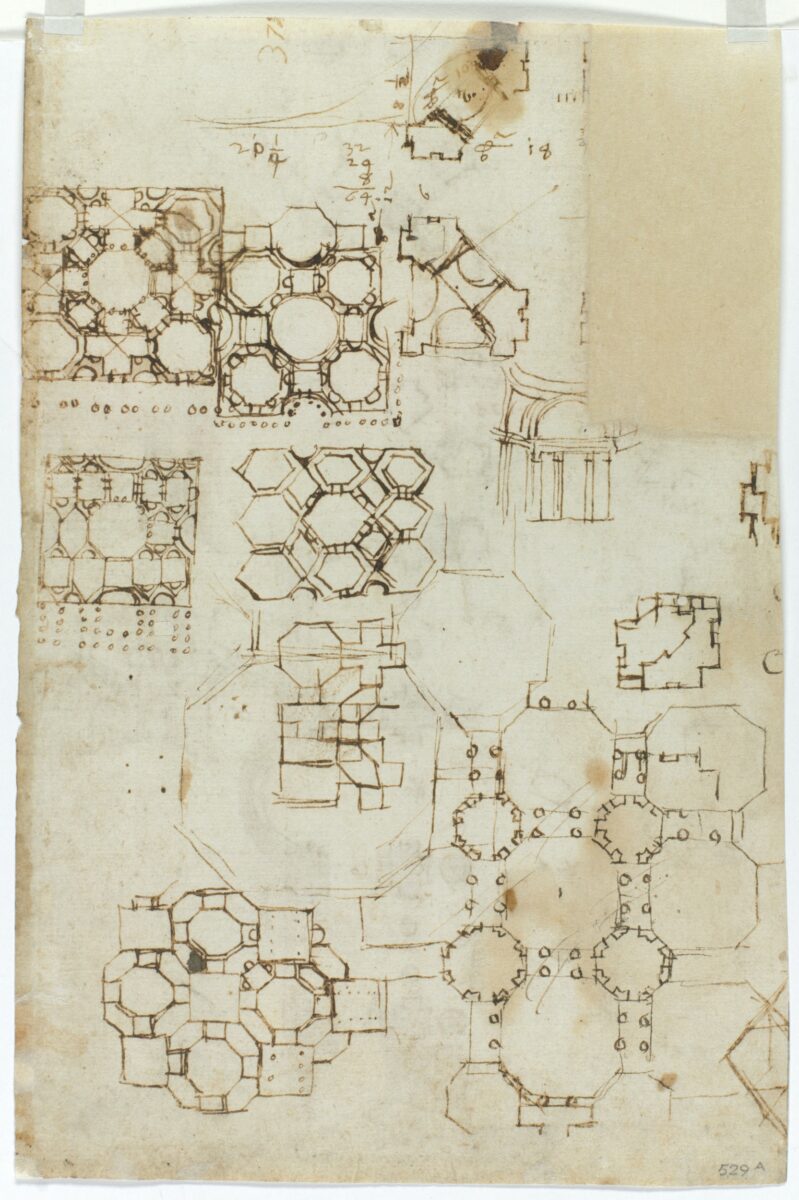

In the mid-fifteenth century, Alberti described a process in which the activity of making the disegno-design took place mentally before its recording in the disegno-drawing or model. While painters already linked the act of making a drawing with developing a design, the same idea entered architecture much later. The Florentine architectural writer Filarete, writing not long after Alberti, described de sign as a mental process with an evocative gestational metaphor: ‘Before the architect gives birth, for seven or nine months he should dream about his conception, think about it, and turn it over in his memory in many ways […]. He should also make various disegni in his mind of this conception that he has made with the patron.’[12]

Filarete’s framing suggested that architects primarily used drawing for a recording and communication space, a logical practice considering the relative expense of paper at the time. While his treatise spoke frequently of drawing, it was usually done on reusable boards by a student copying, rather than an architect thinking. Even in painting the practice of intense sketch drawing as a thinking process, what Leonardo would later call componimento inculto, seems to have been recommended primarily as a training process for apprentices rather than a lifelong habit of senior artists.[13] In the sixteenth century, on the other hand, sketch drawing took on more prominence across media, first in the figural arts and then in architecture. The increased availability of reasonably priced paper played a role, but so too did the growing sense that architectural design should include greater consideration of its visual and pictorial effects. The greater ubiquity of disegno-drawing into architectural design processes went hand in hand with a shift in the collective understanding of what the disegno-design of a building should include. Alberti and Filarete possessed a significantly more circumscribed under standing of architectural disegno in both senses of its meaning than Raphael and later practitioners would come to imagine for it.

7. ‘molti dotati d’ingegno non hanno el disegno’

The meaning of disegno shifted considerably throughout the Renaissance, and particularly in the architectural context theorists did not always clearly distinguish their intent. The painter-architect Francesco di Giorgio Martini used disegno, as others would later do as well, to denote a quality inherent to the practitioner: ‘For we see many who have doctrine [dottrina] and do not have talent [ingegno], and many are endowed with ingegno who do not have disegno.’[14] Possessing personal disegno meant more than having good, creative ideas (ingegno) within the context of generally agreed upon qualitative rules (dottrina). To possess disegno as an artistic virtue de noted the ability to translate ingegno and dottrina into an executable design in drawing form: to turn worthy ideas into architecture. In Francesco’s formulation the theorisation of Vasari was already present: praiseworthy architecture could not be created without the ability to draw buildings and draw them well. What Francesco left ambiguous, however, was what constituted the boundaries of well-executed architectural drawing. How, in other words, did an architect with disegno draw? Despite later authors’ efforts to resolve the question, the ambiguity persisted. For many, orthogonal projection circumscribed the do minion of architecture while for others perspective had its uses; for some, highly specific ornamental detail belonged only to the do minion of painting and for others its inclusion guaranteed the architect a crucial measure of aesthetic control. The testimony of extant drawings further demonstrates the manifold and productive tensions in which drawing worked with architecture in the Renaissance, as indeed it does today.

Notes

- For a recent survey, see Cammy Brothers, ‘What Drawings Did in Renaissance Italy,’ in The Companions to the History

of Architecture. Renaissance and Baroque Architecture, ed. Alina Payne (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2017), 104–35. - On the evolving meaning of architetto, see Elizabeth Merrill, ‘The Professione di Architetto in Renaissance Italy,’ Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 76, no.1 (2017): 13–35.

- Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori, nelle redazioni del 1550 e 1568, ed. Rosanna Bettarini and Paola Barocchi, 6 vols. (Florence: Sansoni, 1966).

- ‘Perché il Disegno, padre delle tre Arti nostre, Architettura, Scultura, e Pittura, procedendo dall’Intelletto, cava di molte cose un giudizio universale, simile a una forma, overo Idea di tutte le cose della natura, la quale è singolarissima nelle sue misure; […]. E perché da questa cogni zione nasce un certo concetto, e giudizio, che si forma nella mente quella tal cosa, che poi espressa con le mani si chiama Disegno; si può conchiudere, che esso di segno altro non sia, che una apparente espressione, e dichiarazione del concetto, che si ha nell’animo, e di quello, che altrisi è nella mente imaginato, e fabricato nell’Idea. E da questo per avventura nacque il proverbio de’ Greci; dell’ugna un Leone […].’ Vasari, Vite, 1:111. All translations by author unless otherwise indicated.

- ‘E tutti questi [disegni], o profili o altrimenti che vogliam chiamarli, servono così all’ar chitettura e scultura come alla pittura; ma all’architettura massimamente, perciò che i disegni di quella non sono composti se non di linee, il che non è altro, quanto a l’architettore, ch’il principio e la fine di quell’arte, perché il restante, mediante i modelli di legname tratti dalle dette linee, non è altro che opera di scarpellini e mura tori.’ Vasari, Vite, 1:112.

- For models, see Henry Millon, ‘Models in Renaissance Architecture,’ in Italian Renaissance Architecture from Brunelleschi to Michelangelo, ed. Henry Millon and Vittorio Lampugnani (London: Thames and Hudson, 1994), 19–74.

- ‘Uti qui sua velit non apparentibus putari visi, sed certis ratisque dimensionibus annotari.’ Leon Battista Alberti, De re aedificatoria (Florence: Nicolaus Laurentius, 1486), II.i. English translation in Alberti, On the Art of Building in Ten Books, trans. Joseph Rykwert, Neil Leach, and Robert Tavernor (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1988).

- ‘E perché el modo del dissegnare che più si apartiene allo architecto è differente da quel del pictore, dirò qual mi pare conveniente per intendere tutte le misure, e saper trovare tuti li membre delli edificii senza errore. El dissegno adunque delli edificii pertenente al architecto si divide in tre parti, delle quali la prima si è la pianta, o voglian dire el dissegno piano; la seconda si è la parete di fuora, con li suoi ornamenti; la terza è la parete di dentro, pur con li suoi ornamenti.’ Raphael and Baldassare Castiglione, “Letter to Leo X,” 1519–21, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Cod. It. 37b, fols. 84v–85r.

- ‘Iccirco vetus optime aedificantium mos mihi quidem semper probabitur, ut non perscriptione modo et pictura, verum etiam modulis exemplariisque factis.’ Alberti, De re aedificatora, II.i.

- ‘Et, per satisfare anchor più compiutamente al dessiderio di quelli che amano di veder et comprendere bene tutte le cose che seranno dissegnate, havemo oltre […] dissegnato anchora in prespectiva alcuni edificii li quali a noi è paruto che cossì ricerchino accioché gli occhi possano vedere et giudicare la gratia di quella similtudine che se gli apressenta per la bella proportione et simetria delli edificii il che non apar nel dissegno di quelli che son misurati architectichamente.’ Raphael and Castiglione, ‘Letter to Leo X,’ Cod. It. 37b, f. 87r.

- Vasari, Vite, 6:109.

- ‘Ma innanzi che lo partorisca, […] l’architetto debba nove o sette mesi fantasticare e pensare e rivoltarselo per la memoria in più modi, e fare varii disegni nella sua mente sopra al generamento che lui ha fatto col padrone […].’ Antonio Averlino (Filarete), Trattato di architettura, 1464, ch. II, f. 7v.

- Ernst Gombrich, ‘Leonardo’s Method for Working Out Compositions,’ in Norm and Form: Studies in the Art of the Renaissance (London: Phaidon Press, 1966), 58–63.

- ‘Siccome noi vediamo sono molti che hanno la dottrina e non hanno l’ingegno, e molti dotati d’ingegno non hanno el disegno.’ Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Architettura civile e militare, Biblioteca Nazionale Comunale, Florence, Cod. Magliabechiano II.I.141, f. 88v, ca. 1492.

Cara Rachele is a lecturer and doctoral programme leader at the Institute of History and Theory of Architecture (gta) of the ETH Zurich.