Retreat and Commemoration: Heath’s Court, 1878–82 – Part 3

This post concludes Nicholas Olsberg’s series on William Butterfield’s Heath’s Court project, the text of which is included in his new book The Master Builder: William Butterfield and his Times to be published by Lund Humphries in October 2024.

‘Sounding corridors’: entry and sequence

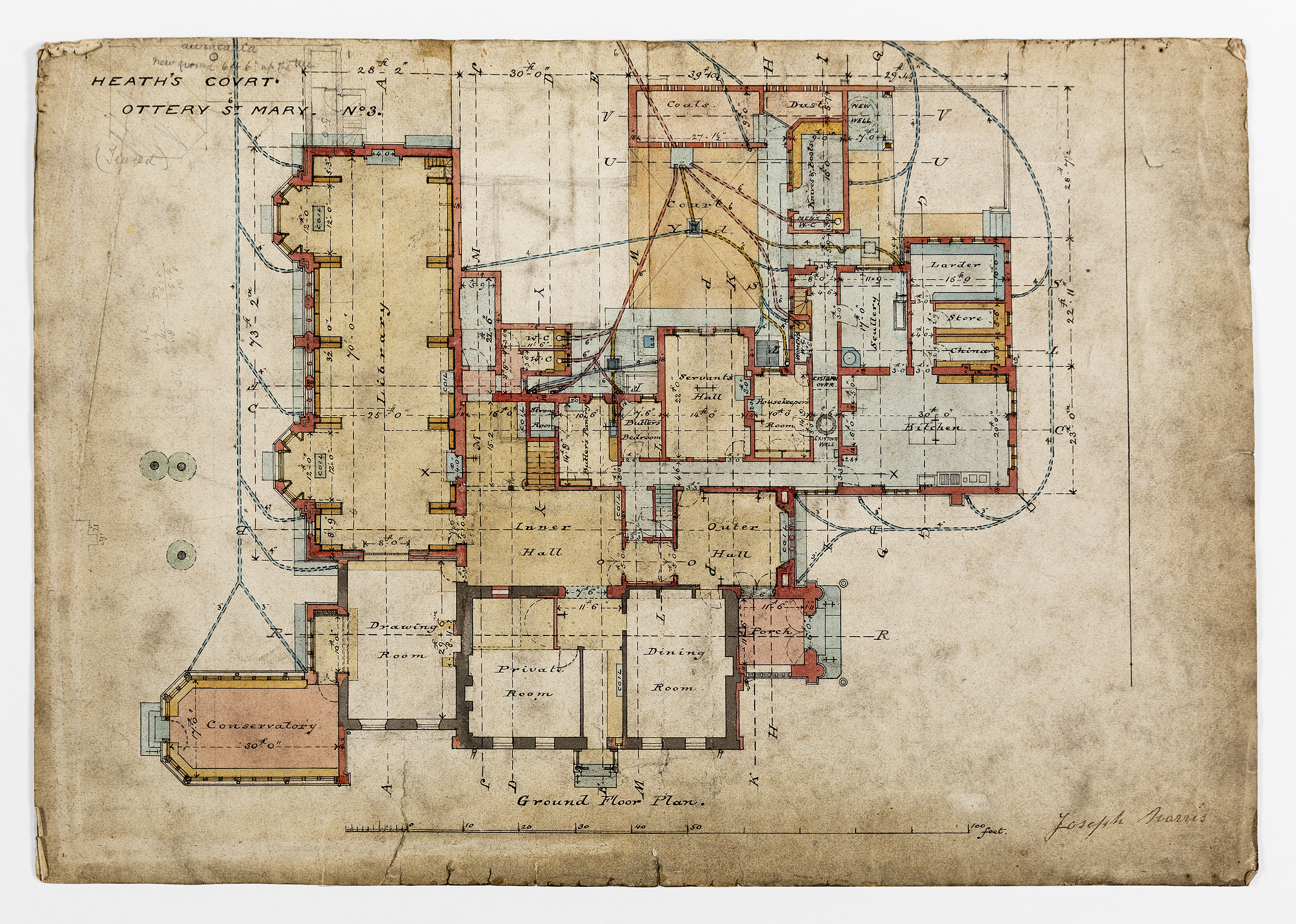

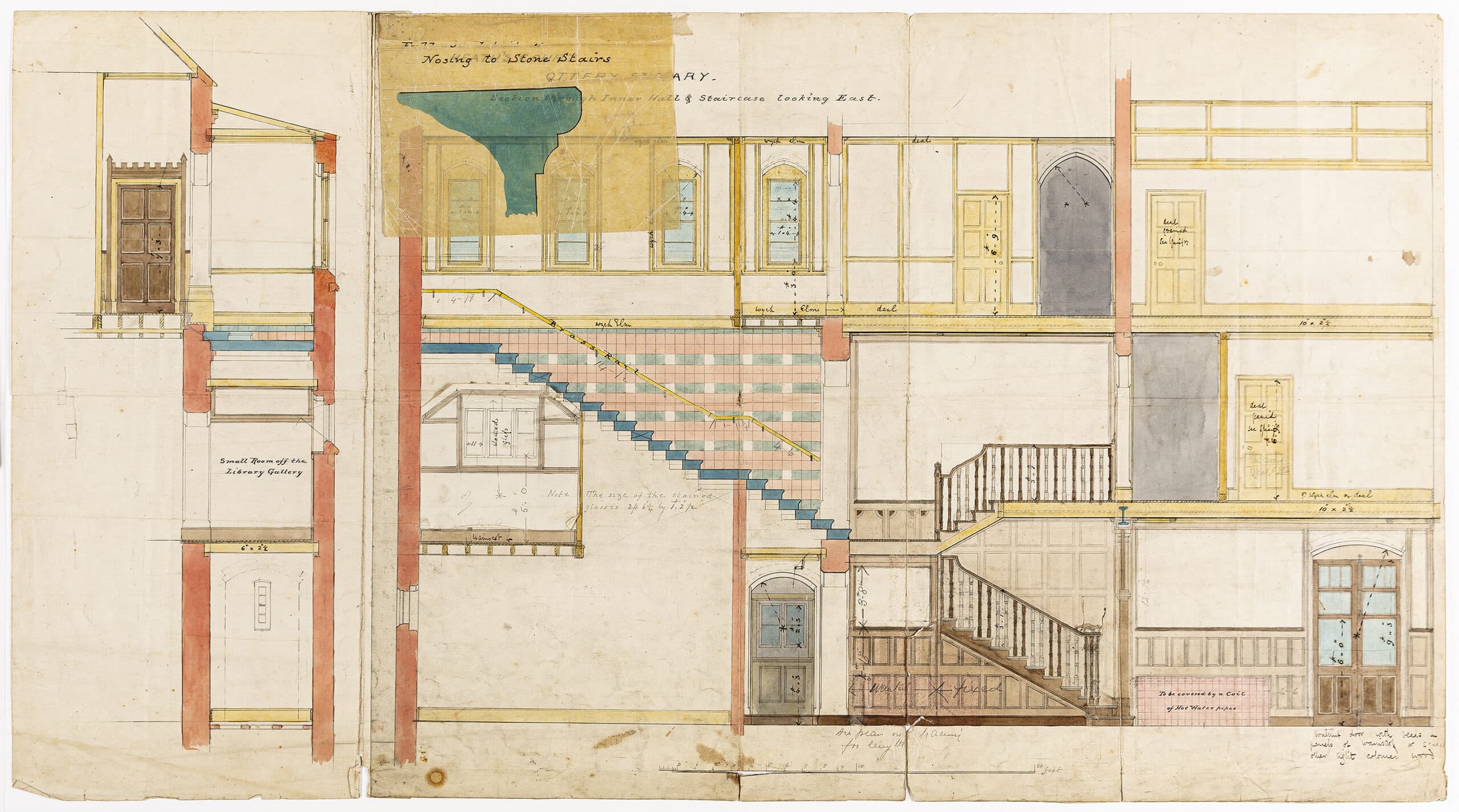

The driveway brings us into a courtyard fit for carriages in which the windows of the kitchen and its corridor lie straight ahead. The entry porch stands to the left, and the entrance takes us immediately through a small efficient portico, turning us right into a reception hall bearing an enormous representation of the Coleridge arms in a cartouche, with a magnificent wall of glass on our right through which can be seen the towers of the church to the east. Though used for household prayers, it is a transitional zone, turning us once again, through a third door, into a short passage, before the last door opens to the inner hall and an almost unexpected vista opens as we enter an atrium from which the whole of the life within branches up and around in a mingling of stair, door, gallery, little window arcades and hidden alcoves, whose shadows and recessions we have already seen beautifully described in the westward-looking section. Nothing could speak more clearly of a house to move about in than this collision and cascade of public routes. Doors were not sentried by a footman; and guests might wander at will. The detailing of the cascade of minor stairs and corridors is unified by red tiles and consistent light-wood simple cabinetry, so that even incidental passages are both animated and coherent.

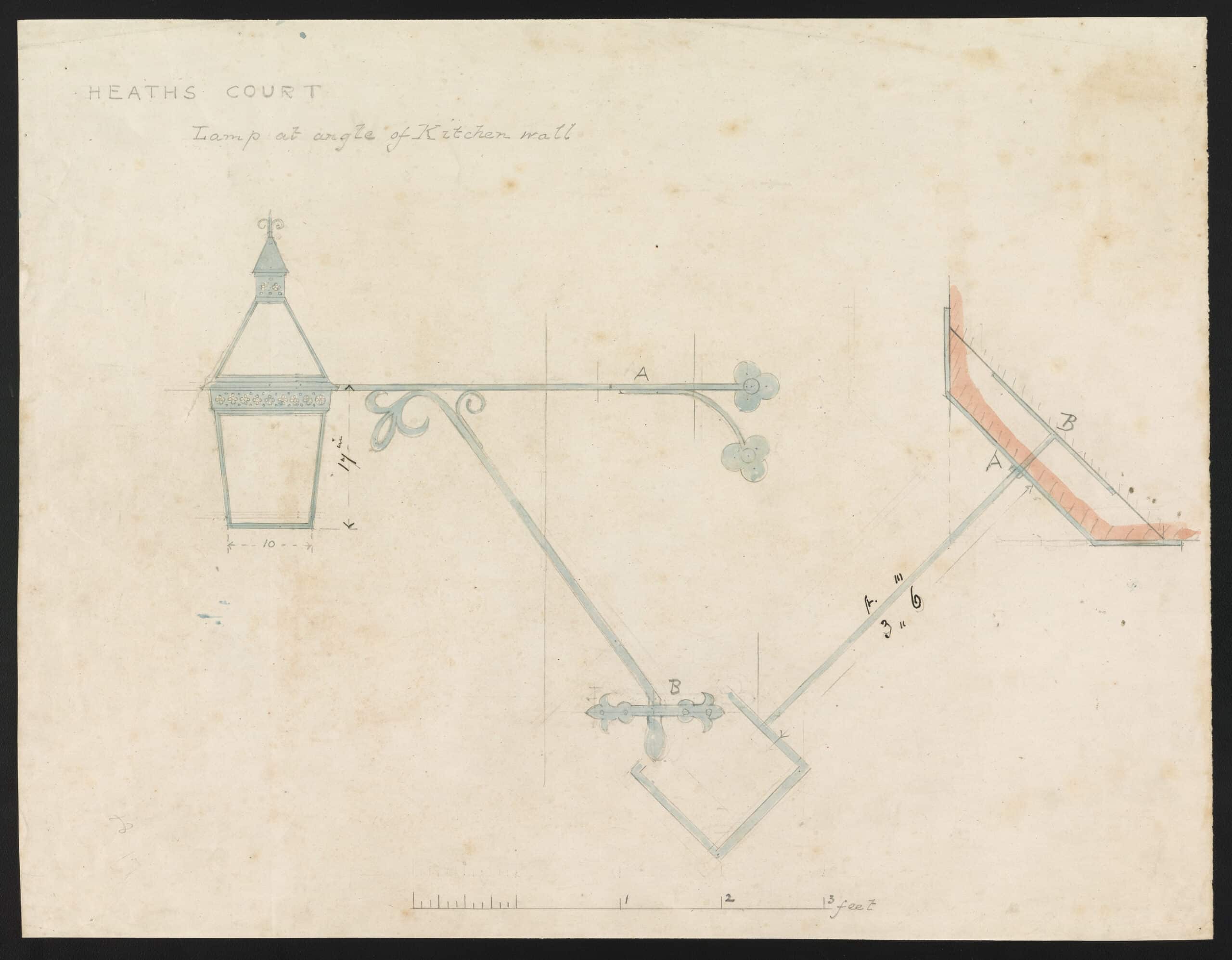

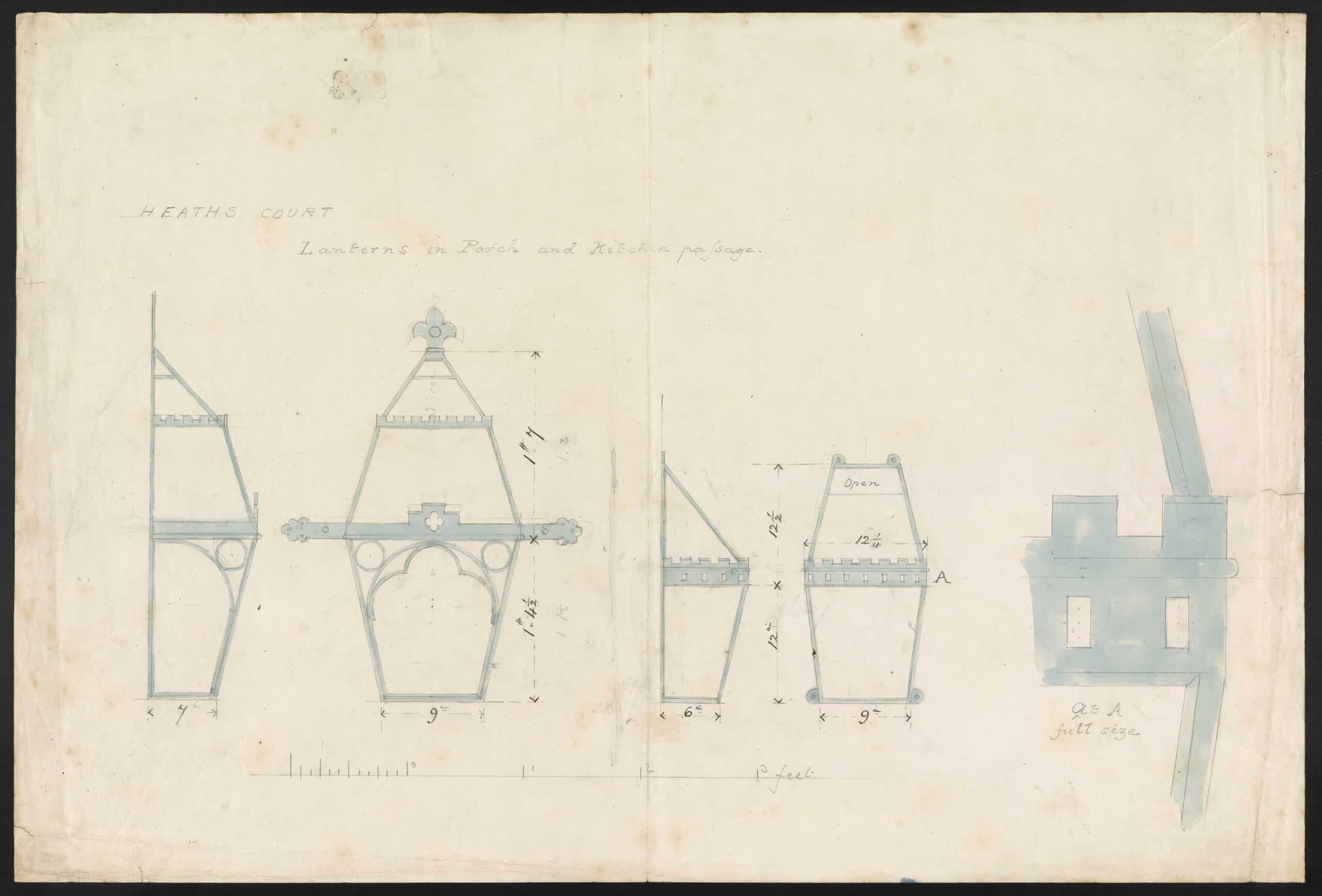

The service areas traditionally buried in a basement were firmly placed above ground and treated with real care. But the serving hierarchy is strictly maintained, with butler and housekeeper housed on the ground floor, their rooms and service staircase seen in the general northward-looking section, while three manservants are housed in a dormitory duplex in an attic above the scullery. The kitchen carries shuttered sash windows placed above head height to allow ventilation without bringing in contaminants; lamps are specially designed to hang high up the kitchen walls and project nearly 4 feet into the room for task lighting. Oriented and windowed to prevent the build-up of heat, it is a mark of the house’s generous provision of pleasure and comfort to those working in it. The attached larder, in which meats might be hung, takes a high gabled shape of its own with stone cold-counters and a set of narrow screened and louvred windows 10 feet high.

‘An English home’: nature and landscape

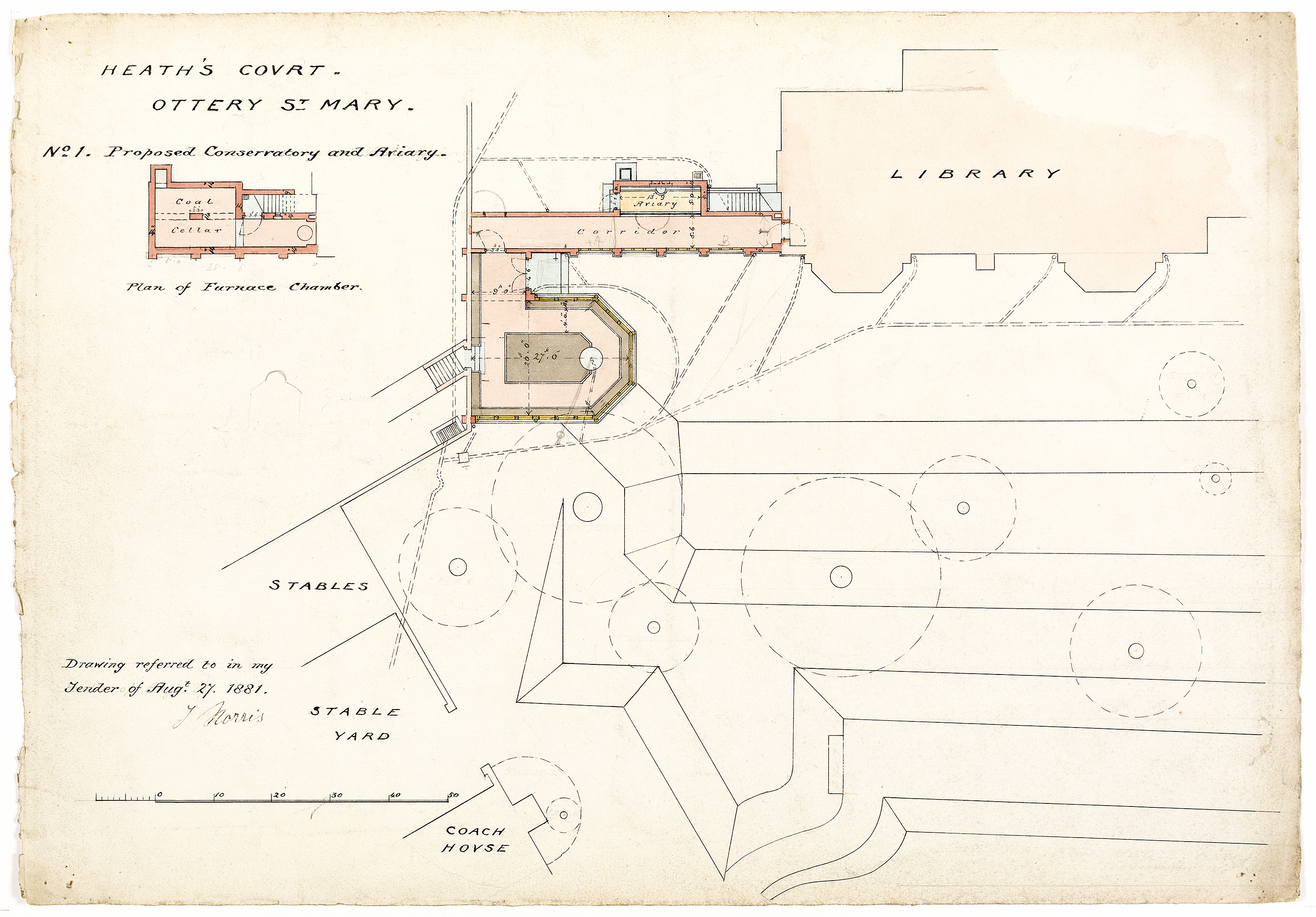

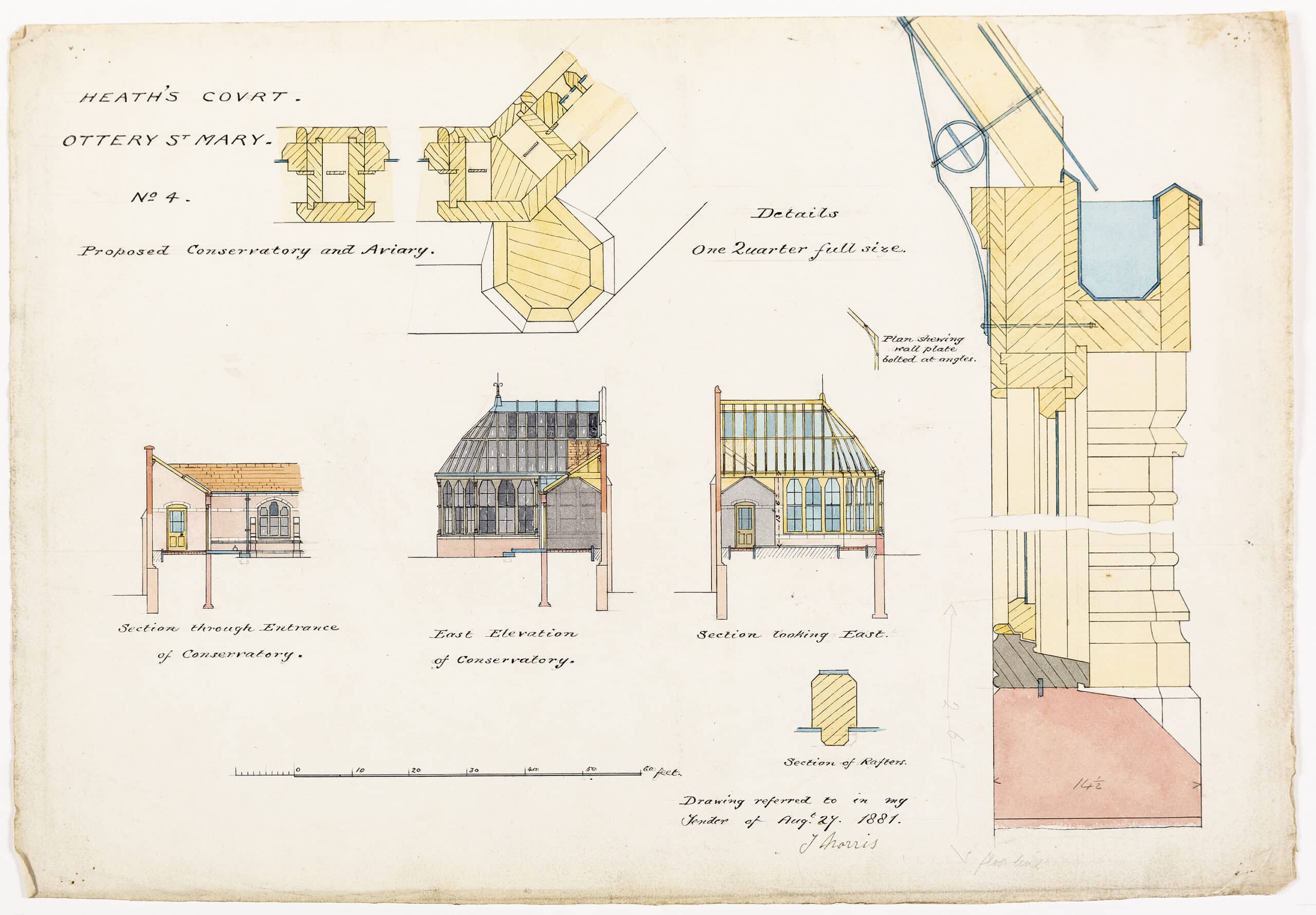

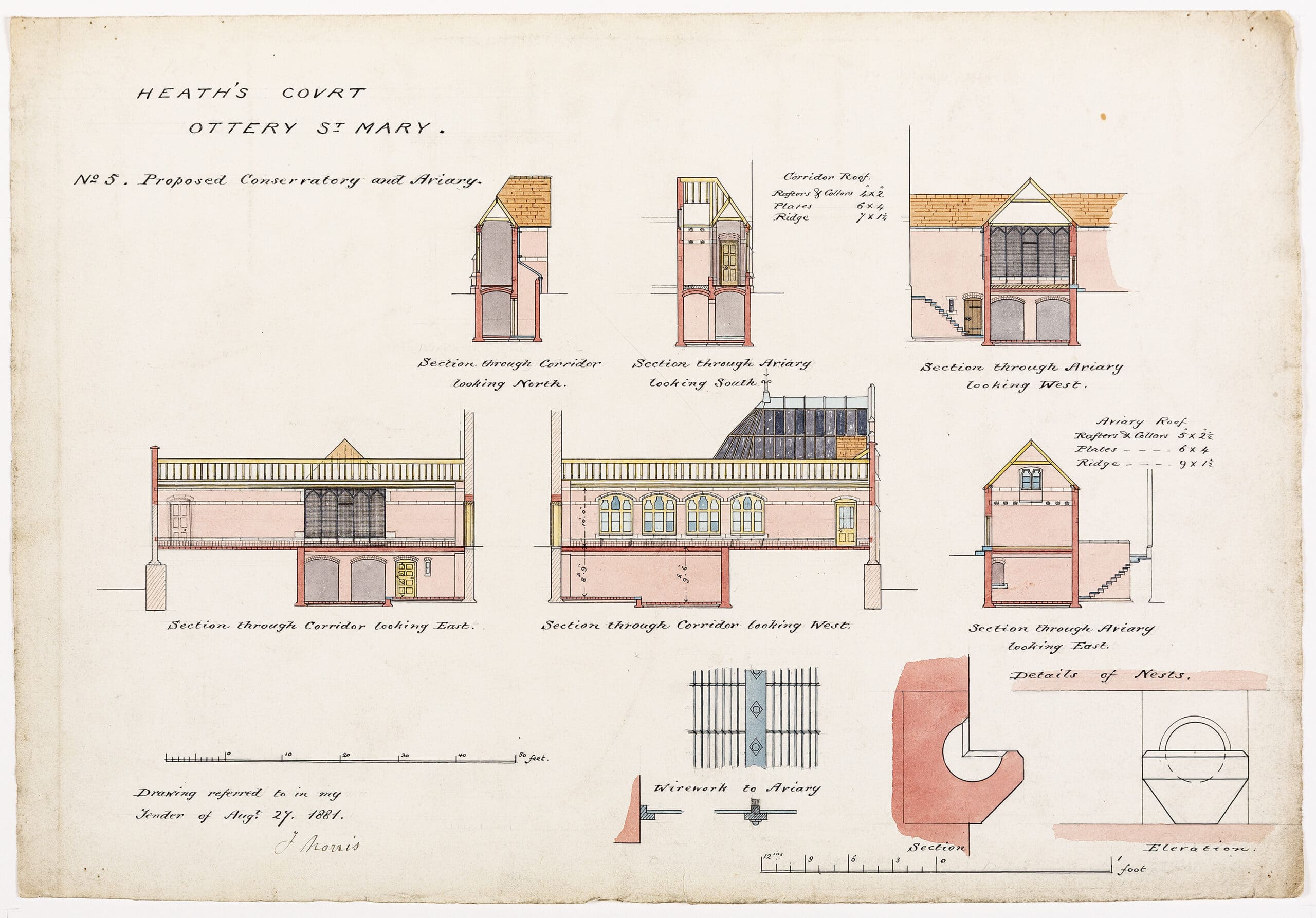

There is a curious effect of assemblage and passage at Heath’s Court, in which within a single enclosed volume the eye catches a variety of spatial transitions and changes in character, as old meets new and one scale meets another, the direction of movement shifts and diverges, alcoves and dead ends appear, public corridors and stairs adopt different dados, railings, woods and turnings, and lamps and lanterns are encountered, hung like those on a city street, like the convergence of a townscape. At its culminating point at the north end of the library, the journey passes through a near-secret door to leave the world of human society behind and enter a long promenade with a city of birds singing on its eastern side and a vista to hilly fields on its west.

Butterfield designed for the comfort of the birds in his aviary scooped hollows for nesting and a stream to drink and bathe. This ambulatory turns at the end into a glasshouse, filled with a fountain, and perched like a turret above falling ground to look away upon the land. Progress ends with ‘The Walk’, nearly half a mile long, that Butterfield wound round the meadow below, past rows of oak planted to mark the birth of sons, among pines sent from cherished friends, to the poet Coleridge’s ‘hilly field’ so loved by Jane that winter grasses and flowers had been cut from it and rushed to London to be beside her in her few last days. These are the grounds of an ‘English home’, replete with memory, and Butterfield calibrated the banks and paths closest to the house to let their canopies spread and their roots flourish.[1]

‘Would you be surprised to hear ? . . .’ This was the phrase with which Coleridge opened each new tale from his inexhaustible storehouse of anecdote. In summer 1883, Coleridge left on a speaking tour of America, returning in October in the company of Amy Lawford, a young woman with a rather uncertain history. London society in August 1885 was ‘surprised to hear’ that Coleridge, whose libellous dispute with his daughter’s lover had already crowded the columns of the yellow press, had suddenly shocked his family by marrying. Nevertheless, Amy, ‘pretty, graceful affectionate and devoted [. . .] made the last years of his life extraordinarily happy’.[2] Smoking and billiard rooms were quickly and rather crudely added to Heath’s Court; and though the new Lady Coleridge told the press that she spent her days lazing in a bay window of the great library, Coleridge was the first to say that she was too young to settle in the country and give up London. So that is where they stayed, with short holidays in a Heath’s Court filled with friends. The long-awaited retirement never came, and he died in office at Sussex Square in June 1894.

The house did not go to Amy, but the chattels were hers, and most of its astonishing collection of books was quickly sold. In the long lists of mourners and friends at the funeral in Westminster Abbey and the burial in Ottery the name of William Butterfield is not found. He had been too ill that winter to attend Butler’s funeral in Lincoln, though he had written the eulogy and made its arrangements, and he seems to have begun periods of seclusion in Bedford Square that would increase into the isolation of his three final years, when his capacities were evidently diminished. But one wonders if in the wake of the marriage and scandals, into which Butterfield had been unwillingly drawn, the paths of these two great friends had diverged. But the mentions of Heath’s Court in the memoirs of that time are fond and legion, as the luxurious freedom of the house is celebrated by Thomas Hardy, Benjamin Jowett and, among many American guests, James Russell Lowell and Henry James (who famously cites ‘the clustered charms of Ottery’, where Butterfield had made such a permeating sense of character that the house itself generated a pervasive sense of ease, happiness and pleasure’).[3]

Notes

- Alfred Tennyson, ‘The Palace of Art’, 1832, revised 1842.

- Lady St Helier, Memories of Fifty Years, Edward Arnold, London, 1909, p.299.

- See Henry James on James Russell Lowell at Ottery in Atlantic Monthly, January 1892, p.50.

Nicholas Olsberg was Director of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal and founding Head of Special Collections at the Getty Research Institute. He holds an honours degree in Modern History from Oxford University and a doctorate in Nineteenth Century history from the University of South Carolina. He has written books on the work of Herzog DeMeuron, Carlo Scarpa, John Lautner, Cliff May and Arthur Erickson, has been a columnist for the Architectural Review and Building Design and has contributed to the curatorial programme of Drawing Matter Collections since its inception.

In the second episode of series two of British Art Matters, Dr Christina Faraday speaks to Nicholas Olsberg about his insightful and comprehensive survey of Victorian architect William Butterfield.