Haunted Venice

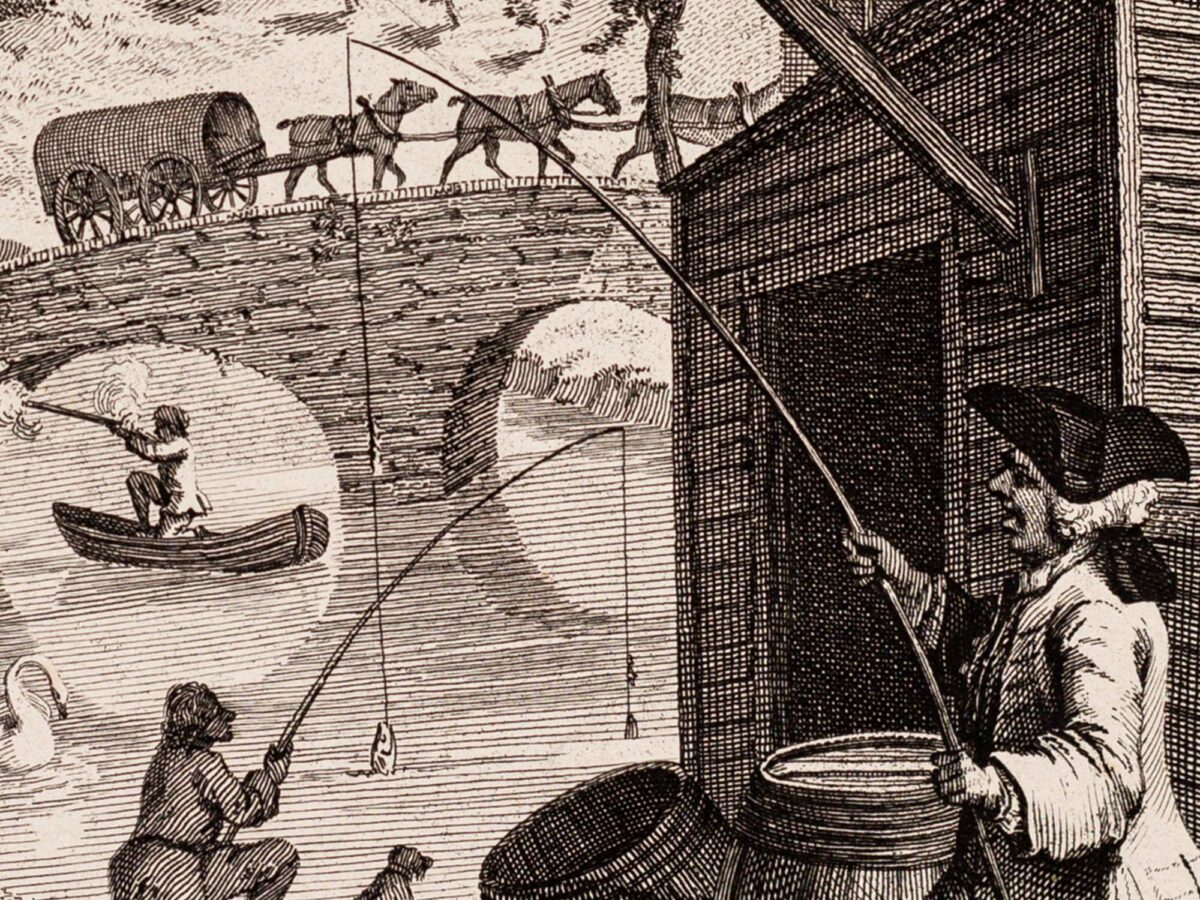

After Niall Hobhouse saw an image of my collage, Venice Haunted, he sent me some comparable images, including a Hogarth frontispiece for a book on perspective theory and practice (1745). Its caption reads: ‘Whoever makes a design without the knowledge of perspective will be liable to such absurdities as are shown in this frontispiece.’ This admonition warns us: beware! Learn and obey the laws of perspective or you may be judged a incompetent fool! And yet, each concocted example is a comic delight, and Hogarth surely must have taken his own pleasure in their invention. Indeed, the drawing provides a site for a game of hide and seek where each ‘absurdity’ found in the hunt is received more as a pleasurable gift than a warning of incorrect behaviour.

This is not the place for a full rehearsal of the invention of perspective and its brief hegemony. Suffice it to say that after five hundred years of perfection and adoption following the Italian Renaissance it managed to thoroughly reframe ‘Western’ spatial imaginations. That is, until a motley demolition crew of 20th-century artists and provocateurs arrived to tear it all apart in search of more realistic renditions of space and perception. Perspective, it turned out, is not a ‘natural’ state of affairs and, as Hogarth reminds us, its complexities must be repeatedly taught and learned, generation by generation, if it is to exist at all. Perspectival images may be optically correct but, as we know, perception is not formed in the lens of the eye, but rather in the brain, and our minds are certainly not bound by the laws of optics. The contemporaneous 20th-century invention of film montage gives us an elegant model of this: each shot may present a perspectivally correct image/space, but these are collaged together through non-perspectival editing devices (cross-cuts, cut-ins, cutaways, match-cuts, dissolves, etc.) busting apart and reassembling time and space. No book of instructions is necessary for this stream of discontinuous images to be effortlessly perceived as a coherent experience, or narrative.

Non-perspectival space/perception is, in this sense, innate and evident from drawings on cave walls through pre-Renaissance painting, where size and position are determined by such things as relative power and importance rather than by measured distances from an observer’s eye. Dazzled by the virtual reality of the perspectival illusion, non-perspectival perception was in retreat until it began to shake itself awake again in the 20th Century. Appearing as a ‘revolution’ it was, in fact, a homecoming, but now accompanied by centuries of perfected and powerful perspectival magic tricks. This time around, representations of non-perspectival space could use perspective itself as a foil, or perhaps a kind of fulcrum, turning perspectival infractions into thrilling new tools. For example, the ‘absurdities’ of Hogarth’s drawing were the main meal for the likes of M. C. Escher and, in other ways, naughty nourishment for surrealist collages.

I encountered surrealist paper collage for the first time in 1981, one year after completing my architectural education, and for me they were a thunderous revelation. The culture of architecture is, if nothing else, a culture of control, and the collaged images of Max Ernst, Hanna Höch, Raoul Hausmann, and others, offered an antidote to this, an easy escape route—all one needs is a collection of old magazines, or abandoned books, a pair of scissors and a little glue. With these simple tools purism may be purged. (I note here that the purism of my architectural education favoured axonometric projections over perspectives—indeed perspectives were forbidden as insufficiently rational or dispassionate, but that is another story.)

Perhaps the Hogarth frontispiece was also called forward because it shares with the Venice Haunted collage the common graphic ‘voice’ of an engraving. Venice Haunted was a very early experiment for me and follows the lead of Max Ernst who used engraved illustrations as the source material for all of his collage novels, beginning in 1929 with La femme 100 têtes (The Hundred Headless Woman). Engravings have a unique predisposition to being fragmented and recombined. They are, first of all monochromatic, so the complexities of colour are removed from the game and, since they are made of nothing but thin black lines separated by thin white spaces, their cut or torn edges meld effortlessly into any other neighbouring edge or surface. Graphically speaking, they practically melt together in new combinations, making them perfectly willing materials for a neophyte collagist.

Something else the Hogarth image shares with Venice Haunted is the game of hide and seek. Both present themselves at first glance, or from a distance, as normal images. Nothing wrong here. But the close observer is rewarded, in both cases, by unexpected events; we find that dissonance haunts harmony. In the Hogarth frontispiece the dissonances are constructed as comical pedantic warnings not to disobey the law, while simultaneously purveying the illicit pleasures of disobedience. In Venice Haunted, the collisions of collage provide dissonances that disturb the ‘normal’ habitual world, offering thrilling little victories over habit and, for me at least, producing a kind of realistic rendition of a disturbed and rejuvenated life.

Since 1981, Mark West’s practice in drawing has preceded and accompanied his technical inventions in fabric-formed concrete architecture. A former professor of architecture, he now lives and works in Montréal Canada at his Atelier Surviving Logic, and since 2023 as co-founder of Ceci n’est pas un musée, a miniature cultural institution also located in Montréal.

PS – Email from Mark West, 7 January 2025

I took the collage out from behind its glass and the thing fell apart like petals. So I put it back together.

It is, once again, almost exactly like its original self, with one or maybe two differences that only I can spot. It was a very interesting thing to do: a forensic examination of my 28 year old decisions. I was surprised (though I should not have been) by the boy’s manic precision amidst a field of chance events — a combination of torn edges and micro cuts . . . The author finds that not much has changed in forty-something years. Anyway it was an unexpected gift to be able to do that today.

I will pack it up good and send it through the post now.

Technical note: the original glue was rubber cement, which I knew perfectly well at the time was anything but archival. I was moving fast back then and revelled in toxic Hexane fumes and was addicted to the redo-ability of that glue. I put it back together again with a Japanese, archival, starch-based, acid-free glue (Yasutomo ‘Nori‘ glue). I think I have the entire thing re-glued. Only time will tell if there are any remaining weak spots.

On Sunday 2 March 2025, Mark West will be delivering a drawing workshop at the Drawing Matter Archive. Find full details here.

– Mark Dorrian and Alberto Pérez-Gómez