From the Poetics of Reality to the Poetics of Memory

Two Drawings by Aldo Rossi

Aldo Rossi’s conception of context underwent a significant transformation over the course of his architectural career, shifting from an emphasis on place to a preoccupation with memory.[1] This evolution is most discernible in his drawings. A comparative close reading of two works—an untitled drawing from 1950 and Composizione con S. Carlo–Città e Monumenti from 1970—reveals the visual articulation of this conceptual shift. Rossi began producing oil paintings between 1948 and 1950, concurrent with the start of his architectural education at the Milan Polytechnic. During this formative period, he was profoundly influenced by the metaphysical drawings of Giorgio de Chirico, Giorgio Morandi, and Mario Sironi.[2]

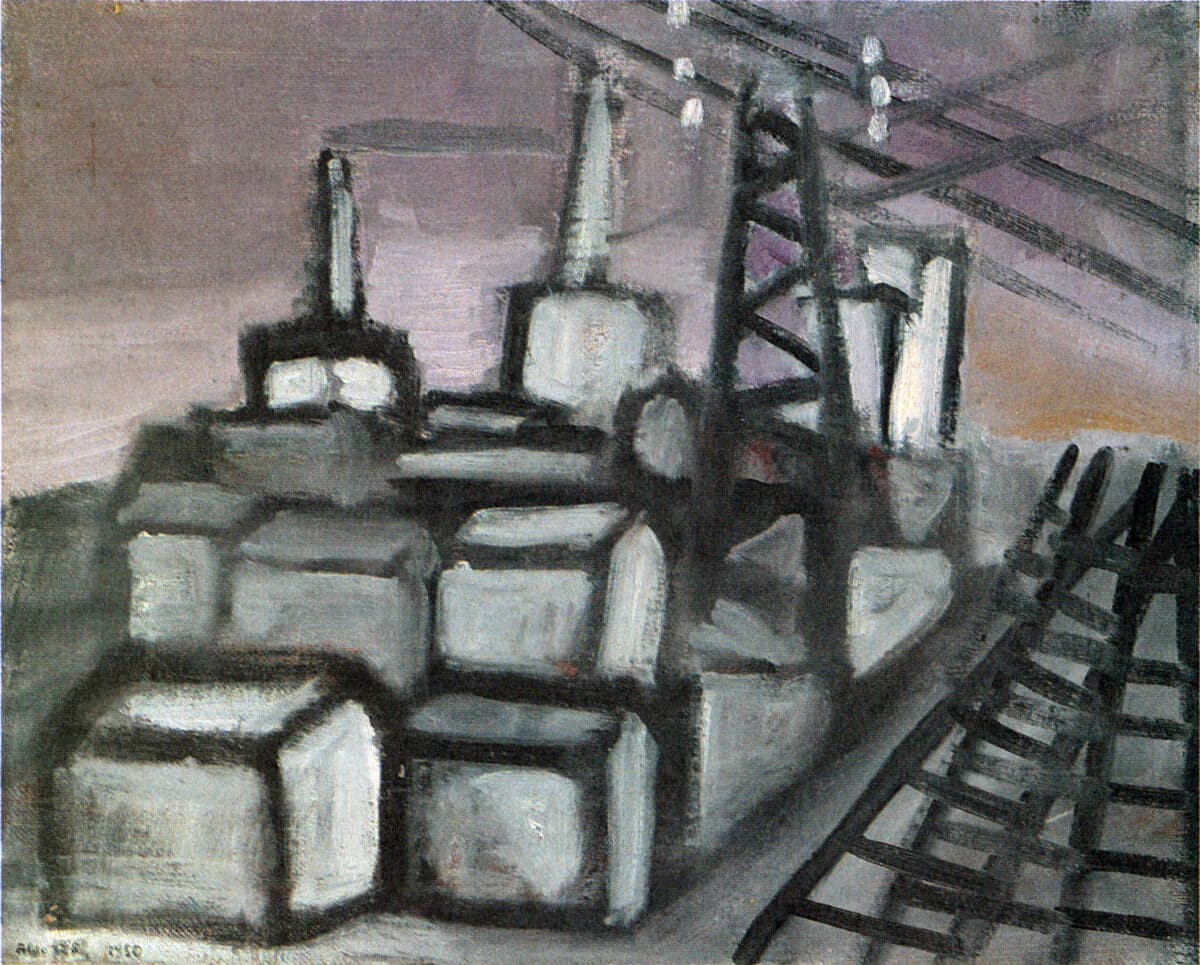

In his early representations, Rossi depicted the industrial periphery of Milan—factories, chimneys, tramlines—as central compositional elements, notably devoid of human presence. These urban artefacts were rendered in elementary forms and volumetric simplicity, often delineated by thick, black outlines. Through this visual language, the rough materiality of the city was foregrounded, emphasising the gritty realism and spatial specificity of the urban conditions.

Rossi’s early theoretical articulation of context, as developed in The Architecture of the City (1966), is structured around three analytical strata: the city, the study area, and the locus. He begins by introducing the city as the context of architecture, proposing it as a pedagogical framework in which the design process is grounded in the analysis of the city. By introducing typological research, Rossi spoke for ‘the progress of architecture as science’ rather than presuming ‘the relationship between analysis and design to be a problem of the individual architect.’[3] In other words, any analysis of the city as a context should be a collective work, and is the responsibility of every architect, in that it cannot be reduced to a singular site analysis.

The second stratum, the study area, refers to the typo-morphologically differentiated urban fragments within the broader city fabric. As an intermediary scale of analysis, the study area facilitates a more focused understanding of the specificities of urban artefacts. The third and most nuanced layer is the locus, defined by Rossi as the art of place, constituted through architecture. In this regard, he critiques Ernesto Rogers’ notion of ambiente—a conception of context as a pre-existing environmental continuum to which architecture merely responds. Rossi, by contrast, posits locus as something that must be actively constructed through architectural intervention. His 1950 drawing can be interpreted in this light: it does not merely illustrate Milan’s industrial periphery but seeks to reveal its underlying spatial and material specificities through abstraction and formal distillation.

This early conceptualisation of context was challenged and reoriented in the aftermath of the sociopolitical upheavals of 1968, which catalysed a disciplinary critique of architectural ideology. Following his suspension from academic teaching and departure from Italy in the early 1970s, Rossi transitioned more prominently into professional practice. From the mid-1970s onward, his architectural thinking embraced a new register—that of analogous architecture—in which the referential integrity of place and time is destabilised. Context, in this later period, becomes an imaginary construct, formulated through formal analogies and personal memory, rather than a direct engagement with the empirical city. The real gives way to the fictive, the collective to the autobiographical.

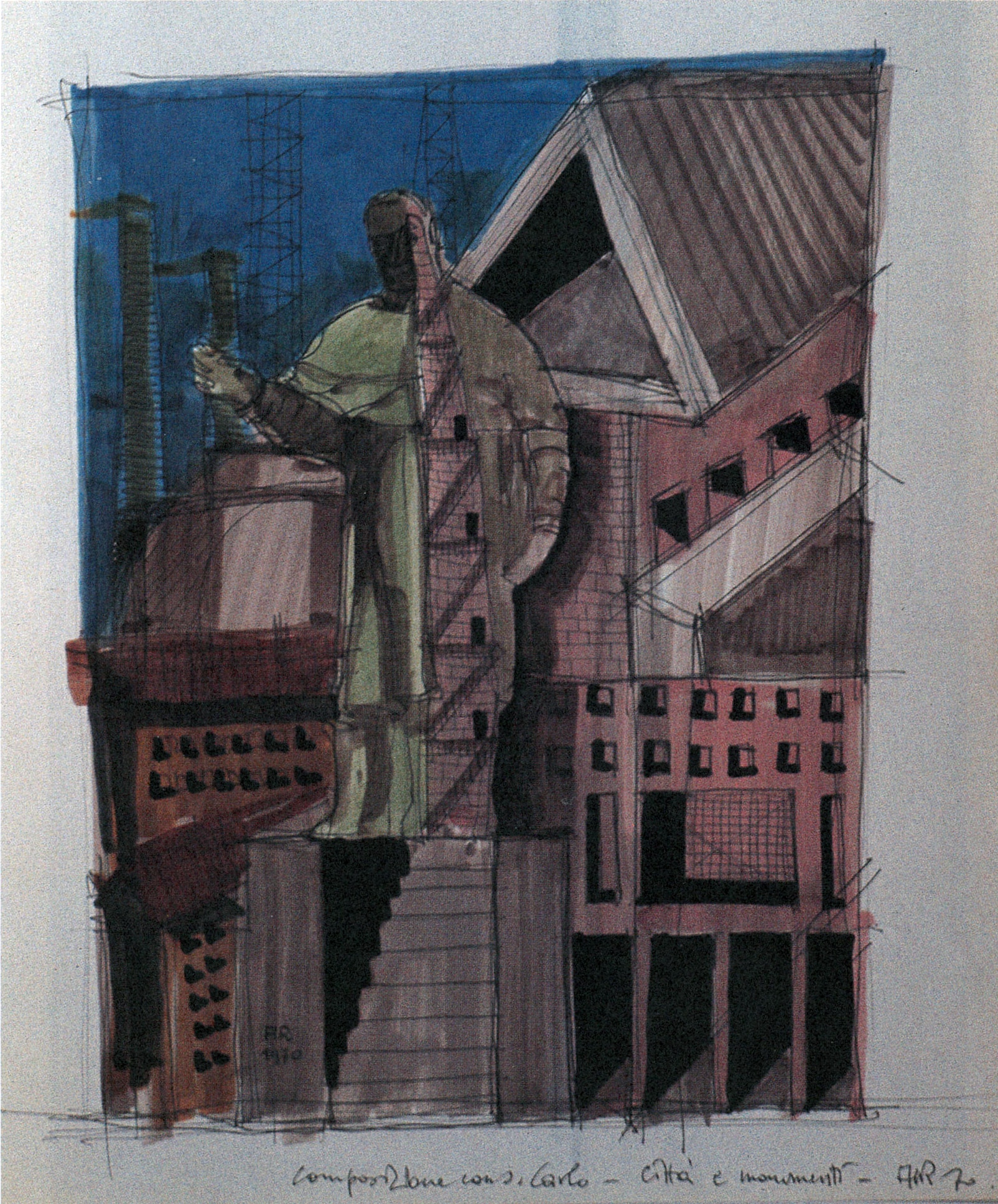

Rossi’s return to drawing in the early 1970s—after nearly two decades of interruption—marks the visual manifestation of this transformation. His compositional strategies evolved: his drawings became denser in content yet lighter in technique, a shift occasioned by his transition from oil to ink and a corresponding adoption of finer line work. Rather than depicting actual urban locales, Rossi drew on a repertoire of remembered architectural elements, drawn from his own built projects and personal experiences. In Composizione con S. Carlo–Città e Monumenti (1970), Rossi assembles architectural fragments from the Gallaratese housing complex, the Segrate Monument, and the Modena cemetery ossuary, along with the statue of San Carlo Borromeo in Arona—a site he frequented in childhood. The statue is rendered with its internal stairway, culminating in a viewpoint that allows the visitor to survey the surrounding landscape ‘through the eyes of the saint.’ These elements, dislocated in time and space, are drawn together at disparate scales and perspectives, thereby suspending any stable notion of context as tied to a specific place and time.

These analogous drawings represent a decontextualised recomposition of architectural memory, producing dream-like visual assemblages. This approach aligns with Sigmund Freud’s theory of dreams, particularly his emphasis on the creation of composite images that amalgamate disparate elements into fantastic forms: ‘The possibility of creating composite structures stands foremost among the characteristics which so often lend dreams a fantastic appearance, for it introduces into the content of dreams elements which could never have been objects of actual perception.’[4] Rossi’s drawings similarly juxtapose elements in ways that defy real-world perception. To achieve this effect, he deployed two key mechanisms of Freudian dream-work: condensation and displacement. These methods enabled the formal compression and transposition of memory fragments, yielding compositions that are both idiosyncratic and spatially ambiguous.

The comparison of the two drawings—one from 1950 and the other from 1970—thus exemplifies the paradigmatic shift in Rossi’s architectural thinking from the poetics of reality to the poetics of memory. The early drawing presents the city as an assemblage of robust geometric forms, depicted from a distanced, elevated perspective. It portrays a city collectively composed of factories, houses, infrastructures, and other elements, representing Milan’s then highly debated industrial periphery. Rossi’s investigations into the urban expansion of Northern Italian cities were initially pursued through such raw, diagrammatic renderings. In these early years, his engagement with the city was deeply rooted in its specificity, as both a physical environment and a historical construct. His perception of the city during his student years was closely tied to a particular place and time, and his principal project for at least the following two decades was to develop a theory of the city capable of offering a rational account of its historical development and transformation.

By contrast, Rossi’s later dream-like, composite drawings reflect a reconfigured understanding of the analogous city, shaped through the memory of his own autobiographical experience.[5] These works, in their suspension of urban specificity, signal a retreat from the tangible city and the materiality of place—a turn toward the imaginative and introspective. Following the 1970s, Rossi’s focus shifted increasingly toward autobiographical expression, moving away from the collective architecture of the city and the constructed art of place. His architectural thinking, along with his conception of context, thus evolved—from the architecture of the city to the analogous city; from collective memory to personal memory; from permanence to remembrance; and from the relationality of architecture and locus to the cross-referential play of forms—a transformation vividly illustrated in the comparison of these two drawings.

Notes

- This text is based on the unpublished Ph.D. dissertation of Esin Kömez Dağlıoğlu, completed in 2017 at the Department of Architecture, Delft University of Technology, titled Reclaiming Context: Architectural Theory, Pedagogy, and Practice since 1950. For a more detailed discussion of Rossi’s understanding of context, the open-access manuscript is available at: https://repository.tudelft.nl/record/uuid:832bb754-82f9-4558-b5fe-1b3bc9ec8358.

- Morris Adjmi and Giovanni Bertolotto, Aldo Rossi: Drawings and Paintings (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993), 161.

- Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1982), 111.

- Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, trans. and ed. James Strachey (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 339.

- For further discussion of Rossi’s concept of the analogous city, see Cameron McEwan, Analogical City (New York: Punctum Books, 2024).

Esin Kömez Dağlıoğlu is an Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture at the Middle East Technical University (METU). She earned her PhD in 2017 from TU Delft, funded by the Huygens Scholarship awarded by the Dutch government. Since 2018, she has been teaching a first-year undergraduate design studio as well as the graduate-level course The City in Contemporary Architectural Theory. Her work has been published in Architectural Theory Review, Thresholds, Footprint: Delft Architectural Theory Journal, OASE, Archnet-IJAR, and METU JFA, among others. She currently serves on the editorial boards of METU JFA and Footprint.