Building with Writing

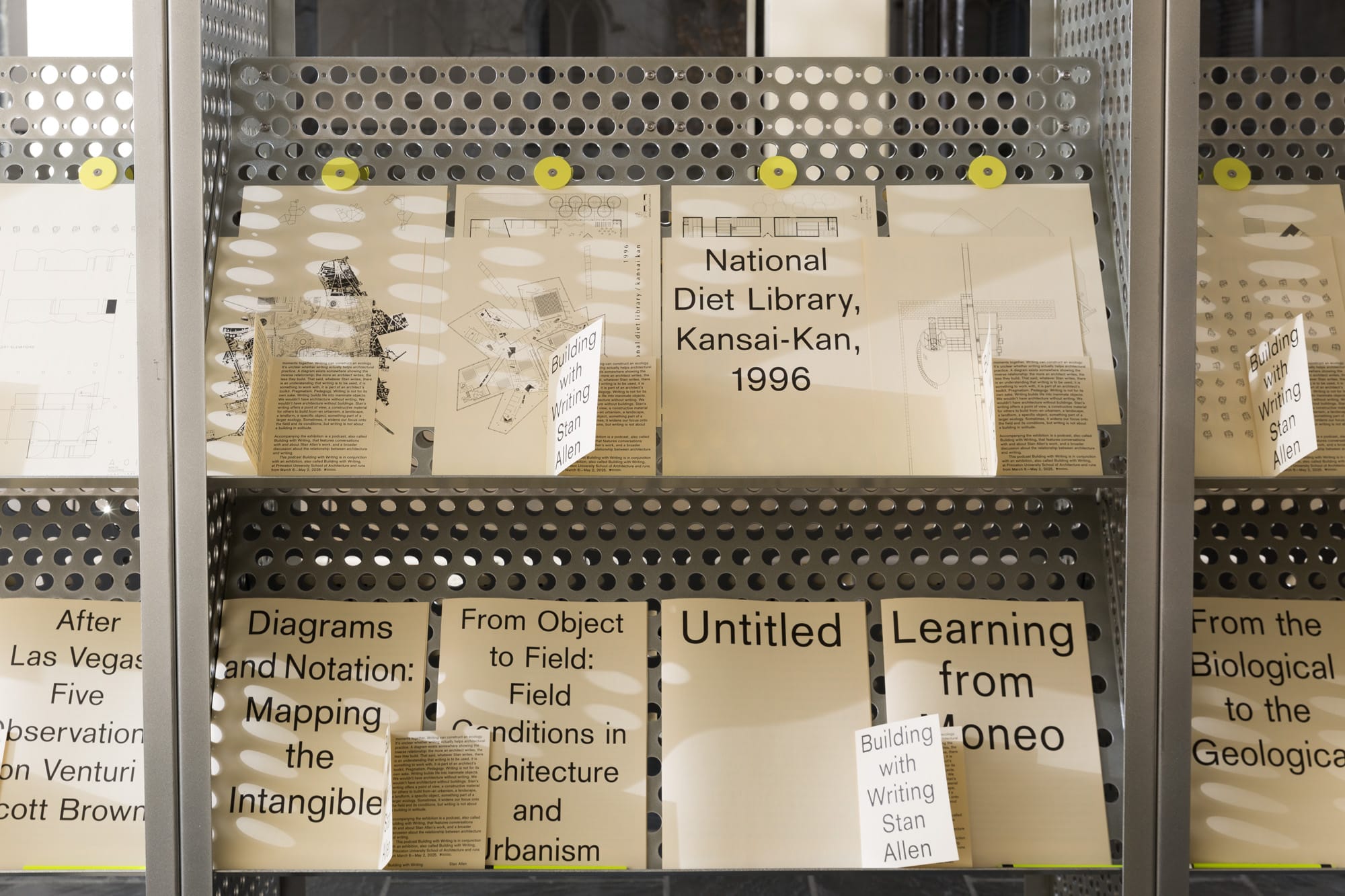

Stan Allen’s exhibition Building with Writing, an installation documenting 40 years of writing and drawing practice, is currently presented at the Graham Foundation as part of the 2025 Chicago Architecture Biennial, led by Florencia Rodríguez, Artistic Director, and Igo Kommers Wender, Associate Curator.

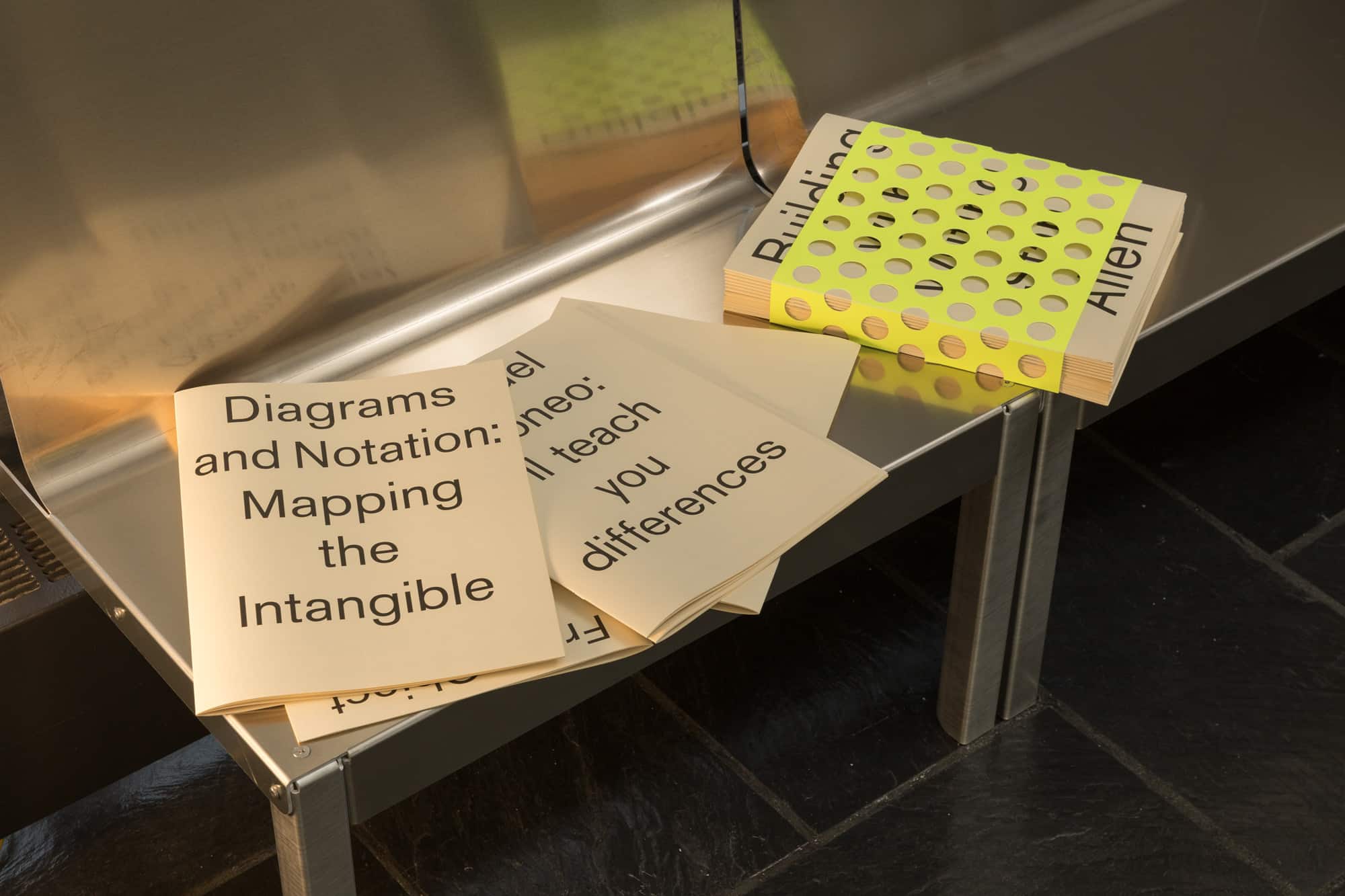

The exhibition was curated by Michael Meredith, with exhibition design by MOS and graphic design by Studio Lin. The original installation at the Princeton School of Architecture ran from March 6 to May 2, 2025.

The following is excerpted from the Curator’s Introduction by Michael Meredith:

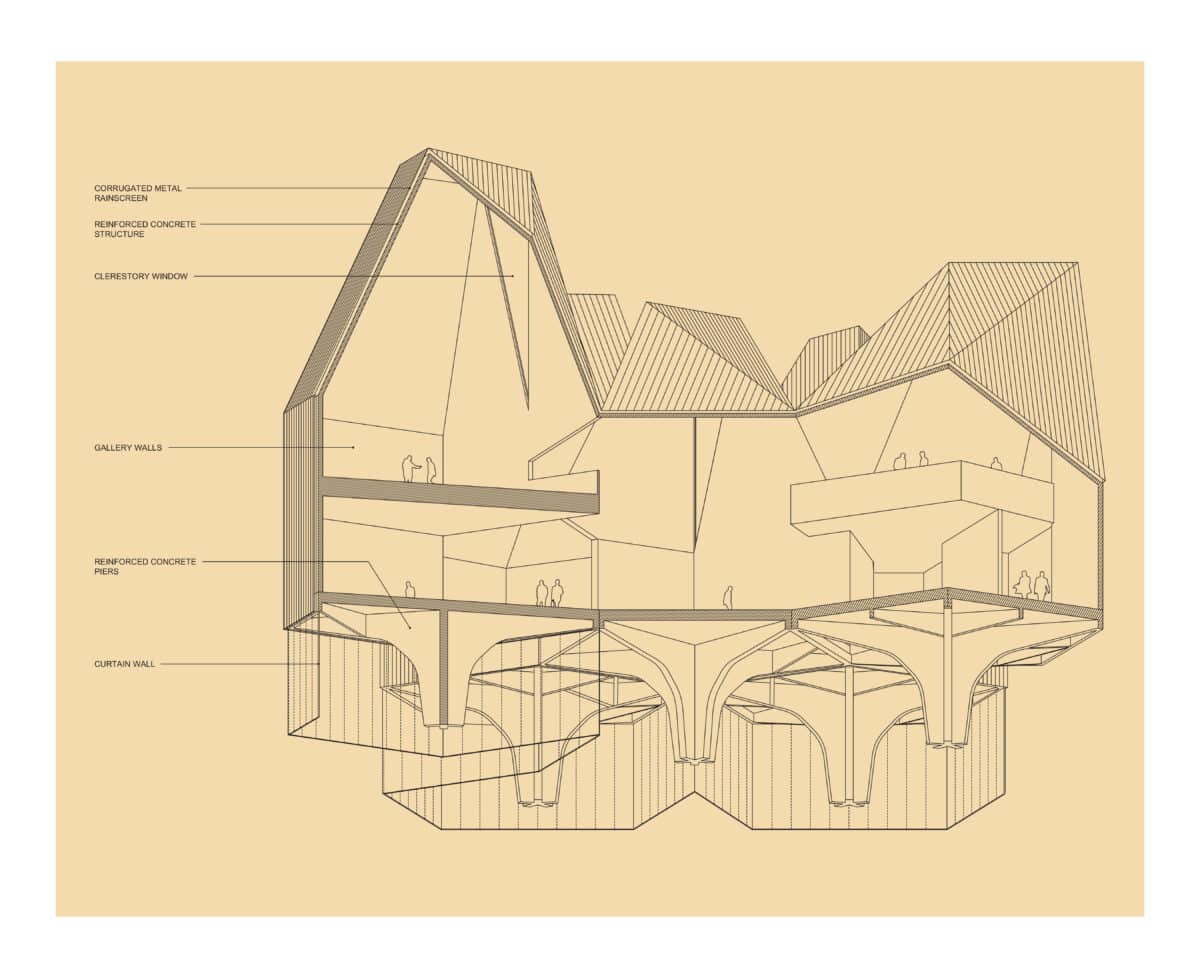

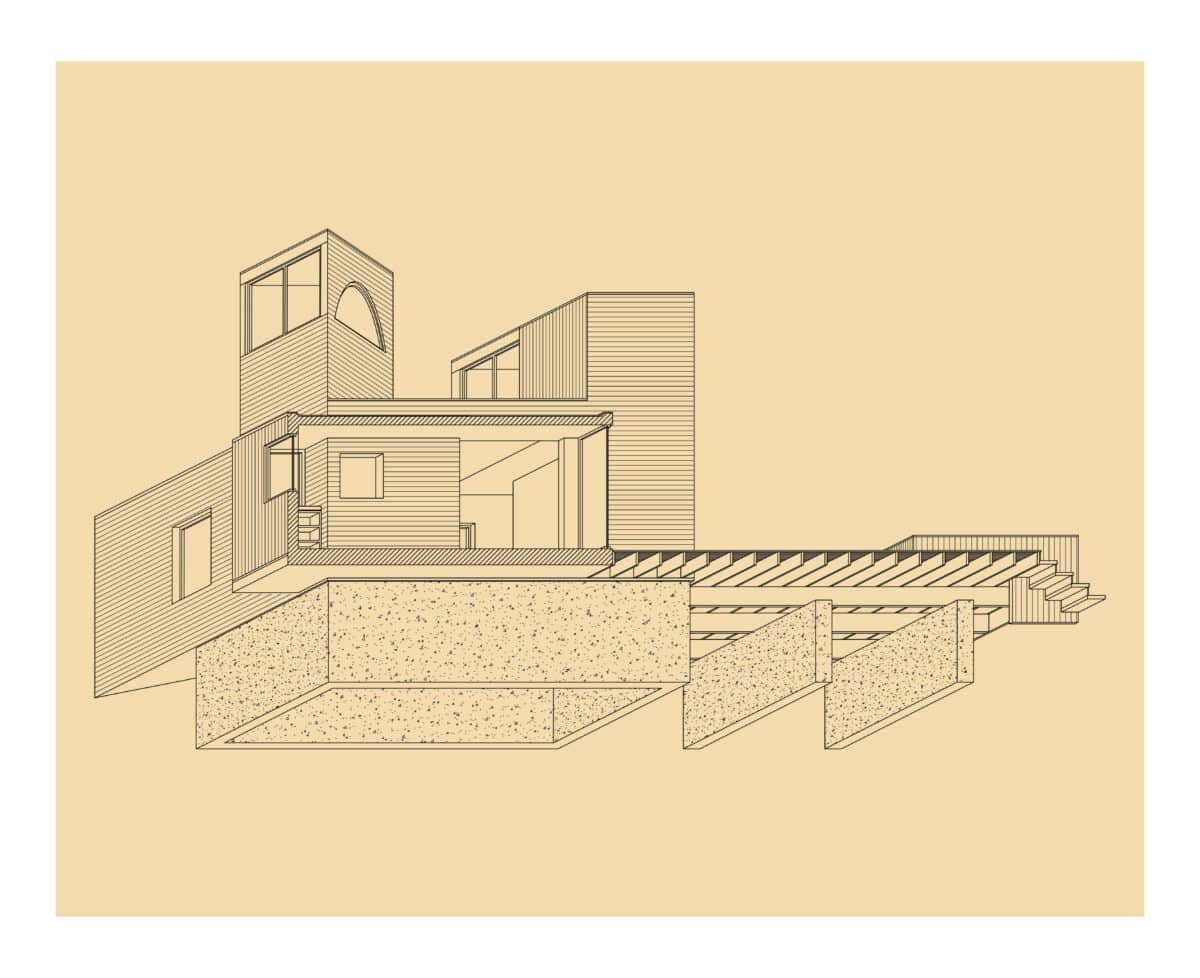

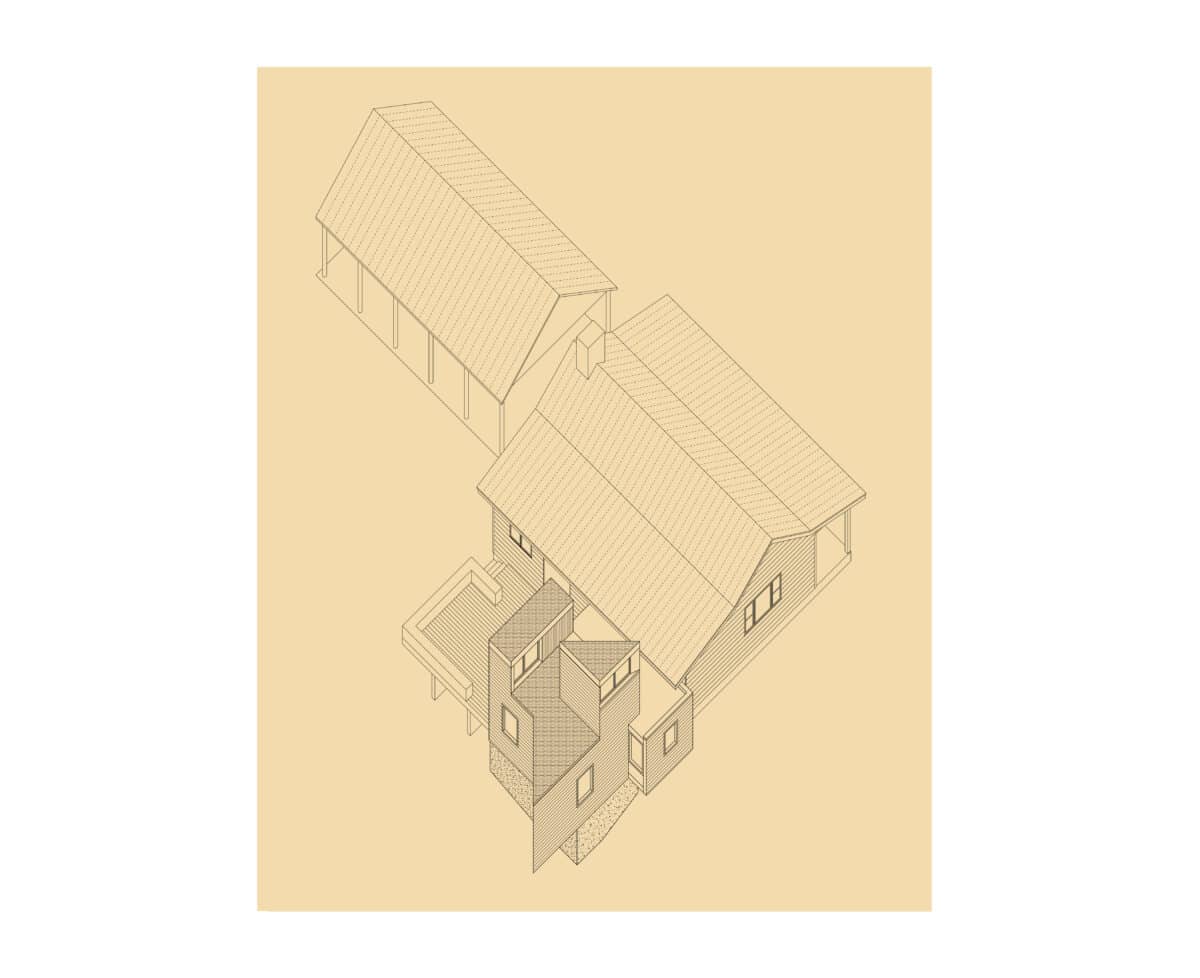

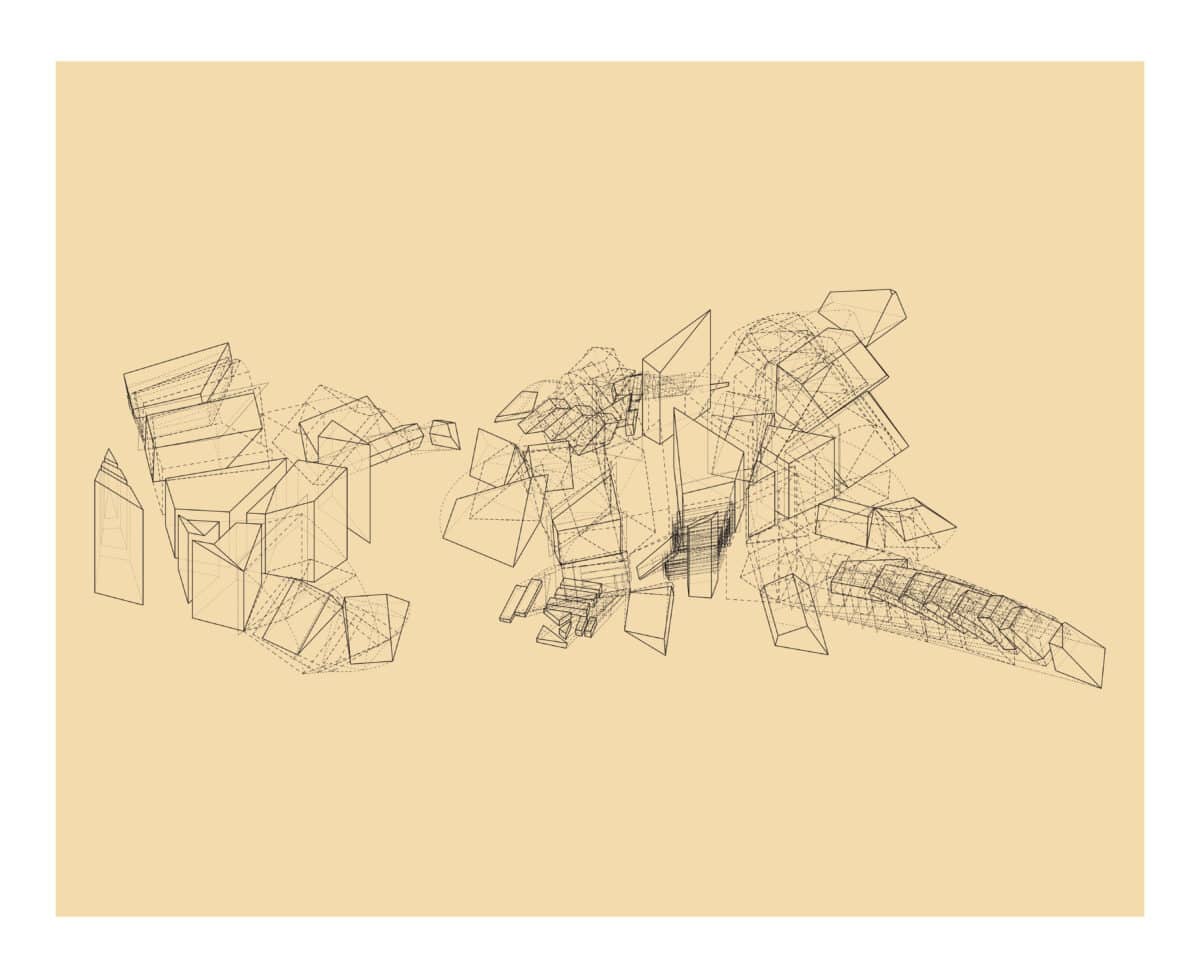

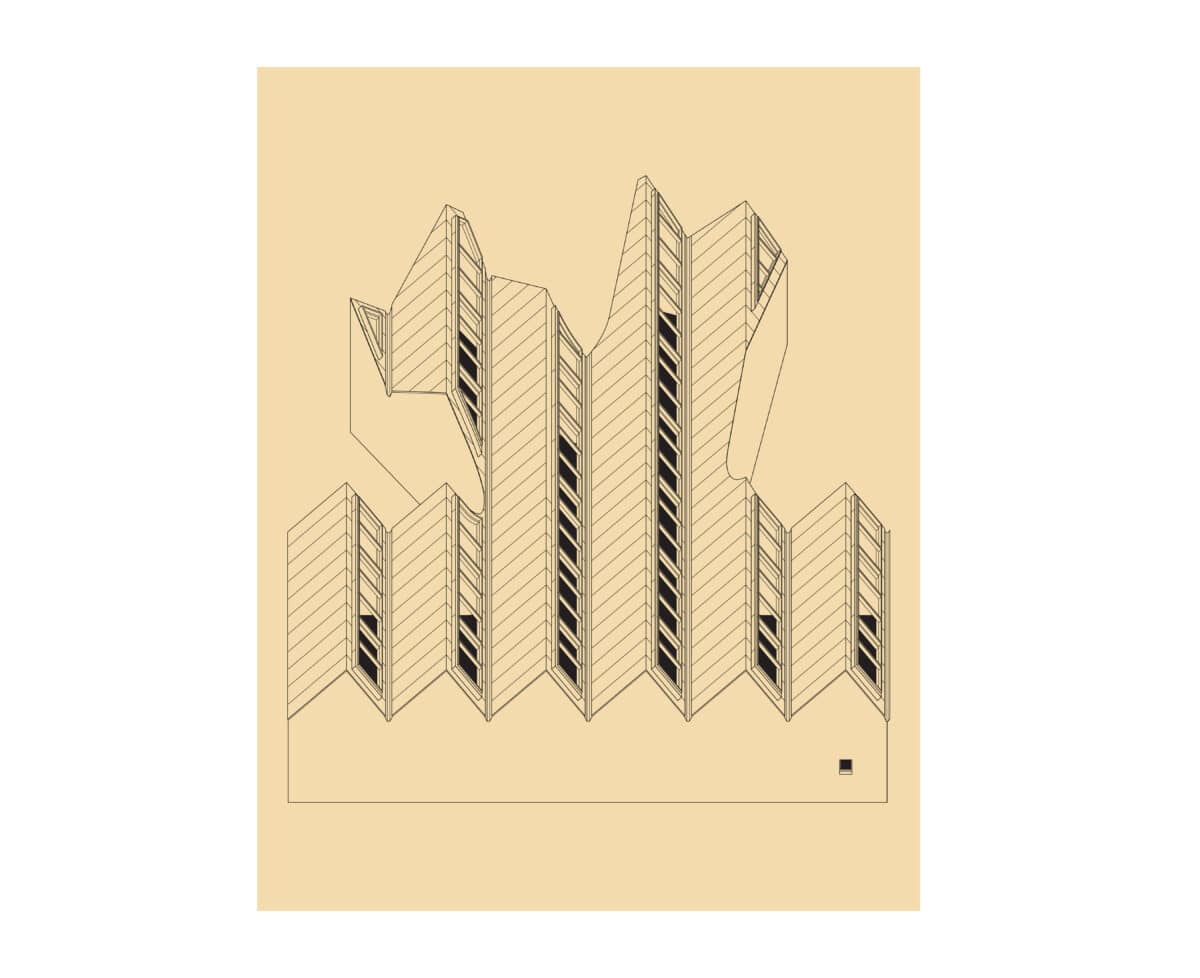

Building with Writing is an exhibition of selected work by Stan Allen. In this exhibition, there are 48 drawings from 12 buildings and 12 pieces of writing, (re)presented as pamphlets. Writing and design are distinct yet parallel practices for Stan; usually kept separate, it felt important to exhibit Stan’s writing and buildings together, next to each other. Everything is presented on folded metal bookstands–something between a bookcase, a medieval scribe desk, and vernacular pitched roofs. The metal bookstands make a reading room with seating for students and visitors. The writings and drawings together make a book to circulate after the exhibition is over. People can read the writing. People can look at the drawings. Architecture can happen somewhere between. Writing provides context for building. Building provides context for writing. Complex. Contradictory. Stan surveys the field. Sometimes Stan writes about architects he likes. He’s written about 30 different architecture offices, which is a lot. There is a wonderful, selfish generosity in writing about others. Writing can tether different people, things, and moments together. Writing can construct an ecology. It’s unclear whether writing actually helps architectural practice. A diagram exists somewhere showing the inverse relationship: the more an architect writes, the less they build. That said, whatever Stan writes, there is an understanding that writing is to be used, it is something to work with, it is part of an architect’s toolkit. Pragmatism. Pedagogy. Writing is not for its own sake. Writing builds life into inanimate objects. We wouldn’t have architecture without writing. We wouldn’t have architecture without buildings. Stan’s writing offers a point of view, a constructive material for others to build from—an urbanism, a landscape, a landform, a specific object, something part of a larger ecology. Sometimes, it widens our focus onto the field and its conditions, but writing is not about a building in solitude.

The text that follows, first published in the final issue of San Rocco, 15: Muerte (2019), was (re)presented as a pamphlet in the exhibition.

Midway through the final year of the twentieth century, two architects died on the same day. And with those deaths, the field was diminished; not just by the loss of two important practitioners, but the loss of two charismatic figures who had, in different ways, defined what it meant to be an architect in that restless century. For John Hejduk and Enric Miralles (as for Alvar Aalto, James Stirling or Louis Kahn), architecture was an all-encompassing pursuit: a lived vocation and not just a profession. They were architects in the fullest sense of the word, as if they had been called to the discipline rather than choosing architecture as one among many ways of making a living.

On the other hand, John Hejduk and Enric Miralles are an odd pair, architects of different generations cast together by the accident of their simultaneous deaths. As far as I know, they never met. They moved in different circles and in the last decade of his life Hejduk travelled infrequently. By contrast, Miralles was always in motion. There is a story of him arriving at the last minute to an AA event looking back at the work of Alison and Peter Smithson. All the other participants shared memories and talked about the Smithsons’ work. Enric showed slides of his own projects, claiming that he hadn’t read past the first line of the fax with the time and date of the event. And anyway, he said, ‘that’s what Peter would have wanted.’ That was pure Miralles: open, unapologetic and unwavering self-confidence.

Miralles emerged out of the fertile intellectual ground of Barcelona in the 1970s. His teachers—the group around Arquitecturas bis—had a steadfast commitment to architecture as a cultural practice, coupled with a belief in the agency of the individual architect. Theirs was a project that was confident in its late-modern precepts, invested in architecture as a discipline, and at the same time expansive in its range of cultural references. It formed the perfect platform for Miralles, who absorbed those lessons, extending and radicalizing the minimalist syntax of his Barcelona School predecessors to the point of personal mannerism. He worked with Albert Viaplana and Helio Piñon before starting to work independently with Carme Piños, and those careful and precise early works, such as the Collegio Badalona in the La Llauna Factory (1984–1991), remain among his strongest projects.

Hejduk, like many of the architects of his generation, served a conventional professional apprenticeship, in his case in the office of I.M. Pei. Educated at The Cooper Union and Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, his response to the late-modern/corporate milieu that he entered as a young architect was a return to the origins of the avant-garde, prompted by contact with Colin Rowe in Texas and Peter Eisenman in New York. His point of departure was early twentieth-century abstract painting, which gave him a model for a self-referential architecture, refining and narrowing its terms in his early work, before opening to narrative and an encyclopedic preoccupation with program in his later work.

They were both large physical presences, big personalities that filled the space around them. At a time when the field was moving toward a global orientation, both were closely tied to specific places: Hejduk to his small house in Riverdale in the Bronx, and to the Cooper Union in lower Manhattan; Miralles to the rambling Gothic palazzo where he lived and worked in the heart of Barcelona. Teaching was fundamental to both. For Hejduk, the Cooper Union was in many ways his most important project, and he spoke of the school as a construction, an edifice in both senses of the word. It is not accidental that the Foundation Building is his most accomplished built work. You feel his presence in the details and fabric of the building: everything is slightly oversized, deliberate and non-fussy. Absolute clarity in space-making, nothing ever thin or cheap. If pedagogy was a self-sufficient project for Hejduk, for Miralles teaching was something that took place in continuity with everything else that he did: drawing, building, travelling, reading, eating. The famous exercise of asking students to produce working drawings of a croissant is typical in this regard—there is pleasure to be taken in both making and consumption.

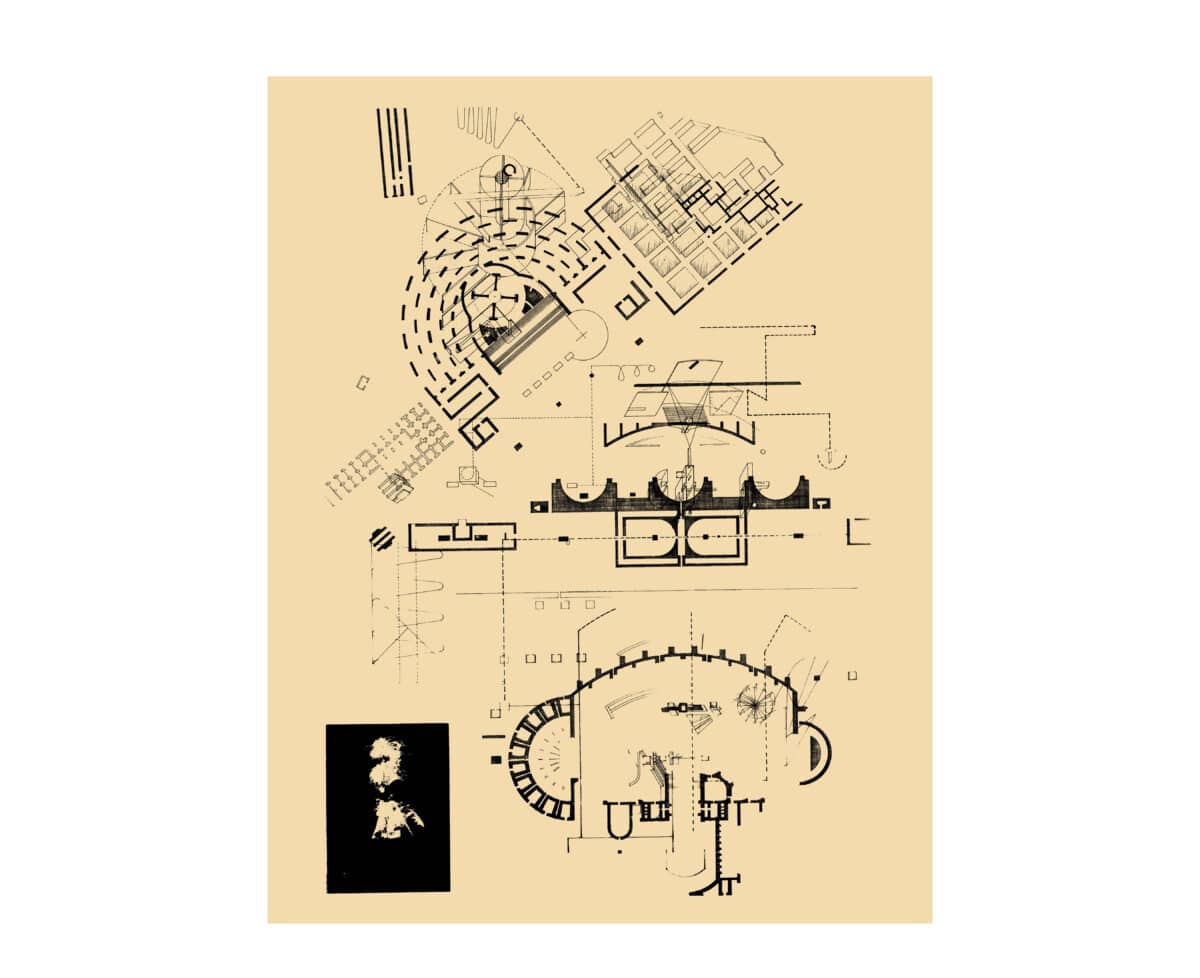

What these architects—so different in many ways—shared was a commitment to drawing and to architecture as a discipline. Both had a deep respect for drawing’s place within the discipline, and in particular, for the agency of the plan. And although you could say that both agreed with Robin Evans that ‘architects don’t make buildings, they make drawings for buildings,’ they were each, in different ways, invested in building. Neither Miralles nor Hejduk (unlike Hejduk’s pupil and Miralles’ contemporary Daniel Libeskind) ever drew a line that did not anticipate its eventual realisation as construction.

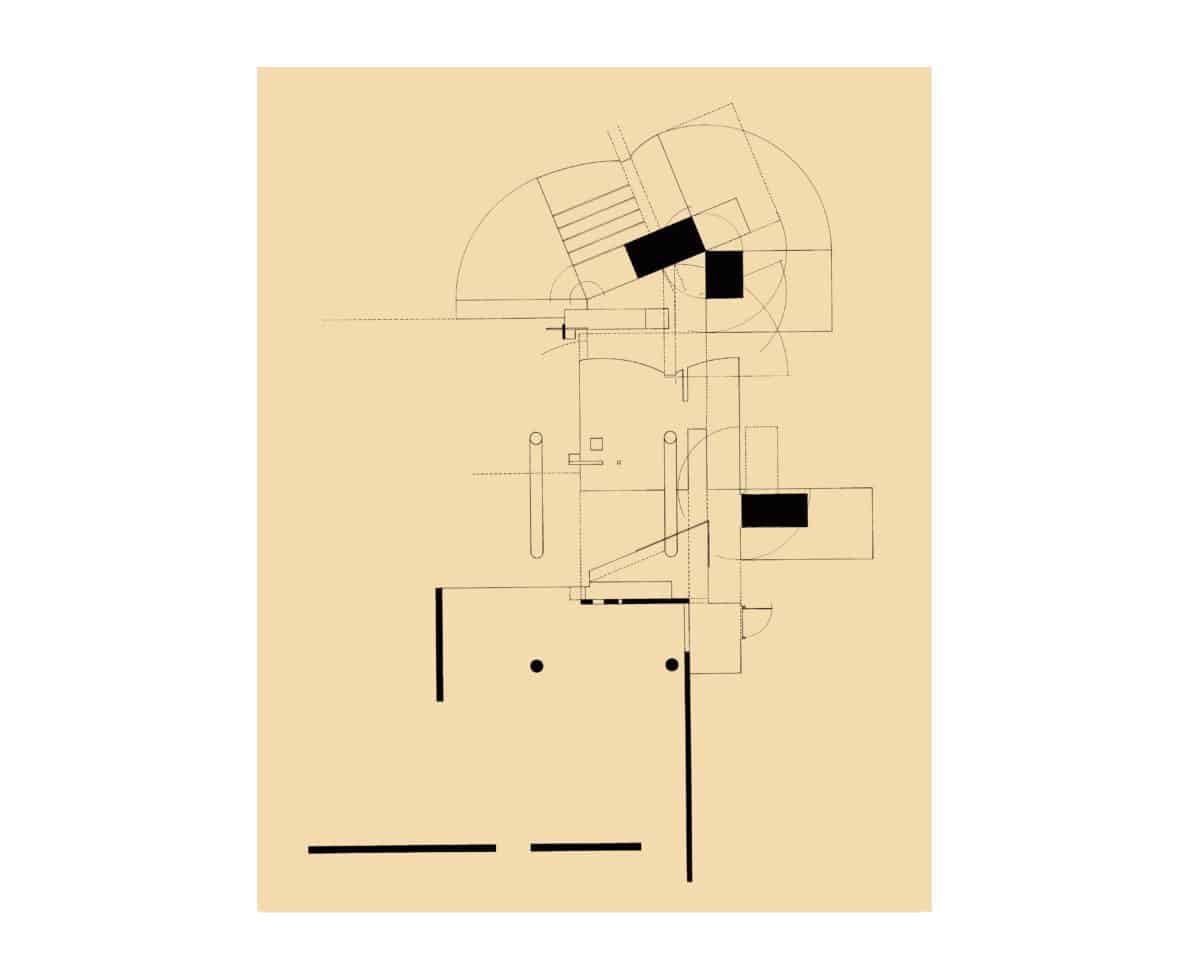

John Hejduk’s two canonical contributions—the Diamond Houses and the Wall Houses—are both plan-based operations. The Diamond Houses transpose the painterly problem of the edge of the canvas to the architectural question of the envelope. While Hejduk was acutely aware of the notational character of the architectural plan, he worked like an abstract painter, addressing compositional problems on the flat plane of the drawing and within the boundary of the enclosing wall. But he also internalised the idea (embedded in Le Corbusier’s dictum ‘the plan is the generator’) of the plan as a working device that anticipates projection and construction. By rotating the Diamond House plan 45 degrees before projecting into axonometric, Hejduk chanced on the 90-degree projection, a drawing that for him functioned simultaneously as plan and elevation. This productive tension between frontality and depth became fundamental to his design practice. The simultaneity of multiple viewpoints and the implied collapse of time and space that he admired in cubist painting found its perfect analogue in a drawing technique, if not yet in spatial terms. But that simultaneity of plan and elevation almost immediately found a more concrete expression in the Wall Houses, which perfected the idea of what Robert Slutsky had called a ‘still-life architecture,’ no longer dependent on operations of projection or illusion. In the Wall House, unlike Eisenman’s more literal translations of the space of the axonometric, the vertical plane of projection becomes an active architectural element and retains the double condition of construction and representation.

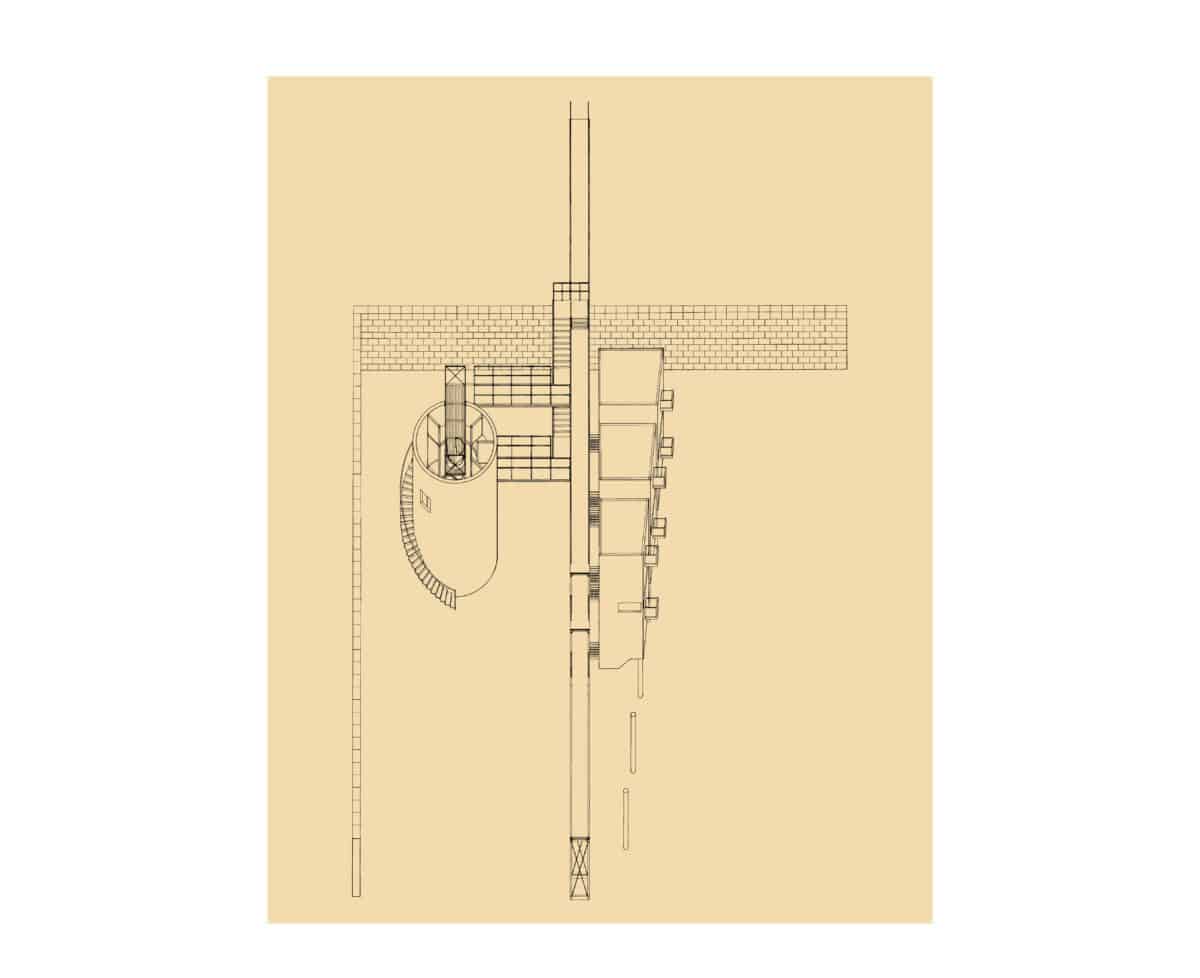

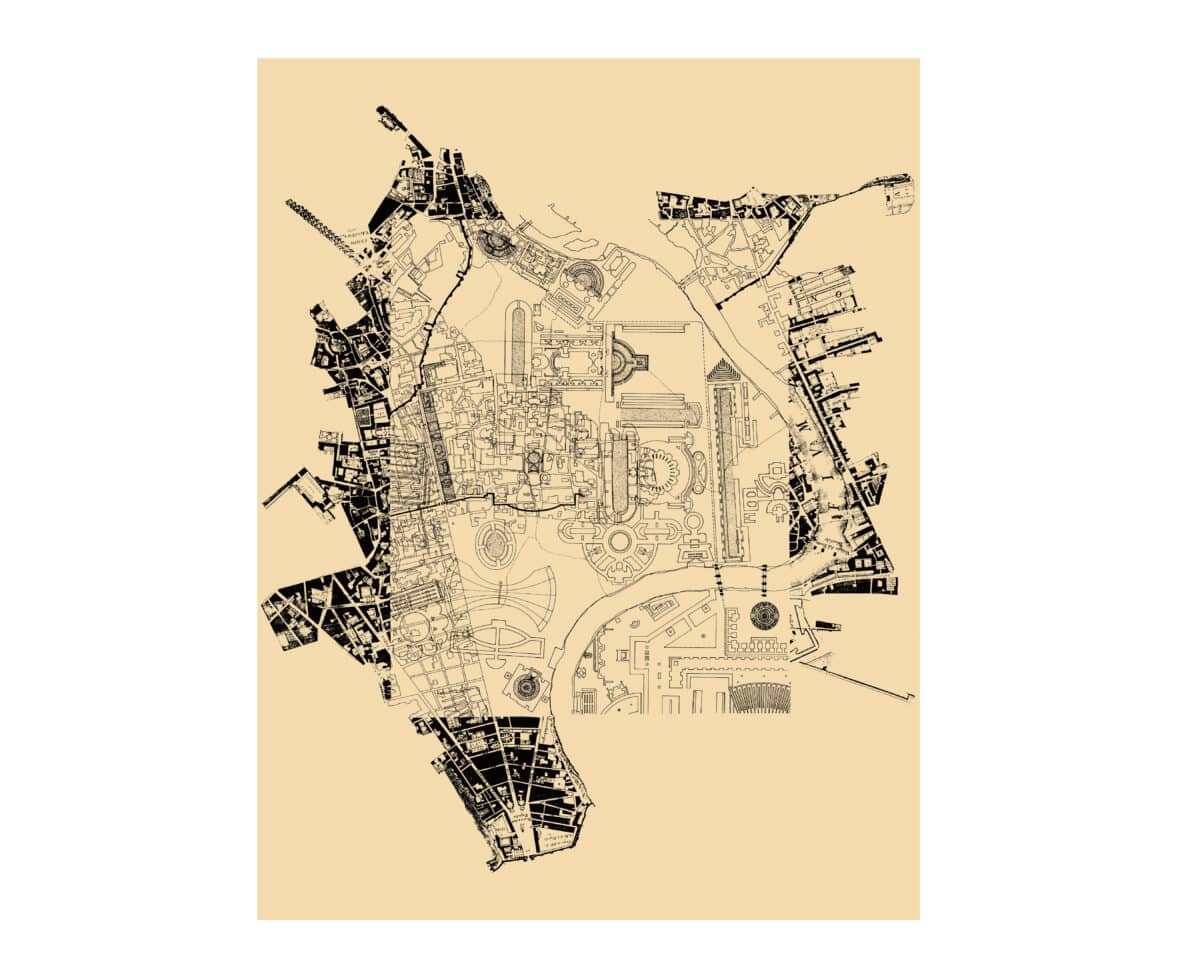

If Hejduk approached drawing through the lens of painting, for Miralles, the act of drawing was connected back to the Anglo-Saxon etymology of the word itself: in English, ‘to draw’ is a transitive verb meaning to pull, or drag, something: a draught horse draws a cart. For Miralles, each line was a trace actively pulled across the page by the hand, a vector with intention and trajectory, something immediate and physical. In this sense, the Archery Range for the Barcelona Olympics, completed by Miralles and Piños in 1991, was the perfect realisation of this approach. Lines in a Miralles drawing can mean many things: alignments, wall edges, projections, the edge of a beam above, steps, handrails, or material changes. He populated his drawings with all kinds of lines, and this proliferation of marks made his drawings into a dense web of notational information that anticipates construction but does not necessarily describe a building in any direct way. The method is a risky one and the buildings did not always deliver on the promise of these beautiful drawings, but the Archery Range comes very close. The pavilions—realised in pre-fabricated concrete under a very tight construction schedule—map out an implied spatial field larger than the actual building. The web of lines in the drawing is not translated literally but is present in the experience of the space.

It is a telling episode, because both architects had an ambivalent relationship to building and construction. Hejduk’s career is marked by doubt. He was acutely aware, perhaps more than any other architect of his generation, of the dilemma of having arrived late to the modernist experiment: ‘We’re born, you could say, appropriately, too late, because there’s a lot of architects in my generation running around thinking they’re masters. A generation before or two generations were masters, I mean real masters of architecture.’[1] The definitive accomplishments of Wright, Le Corbusier, Mies, and to some extent Kahn, cast a shadow over his own work. And if that early-modern work was characterised by certainty, Hejduk’s response was an architecture of doubt. This sense of lateness, of questions already posed and already answered, pervades his work. He desperately wanted to be part of the grand modernist experiment but knew all too well that by the time he started to work it was already in crisis. I remember him saying once that when the doctors eradicated tuberculosis they deprived modern architecture of its best program. This nostalgia for what he called the ‘panoramic’ project of modernism pushed him more and more to the margins.[2]

Miralles felt no such weight, or obligation to move toward the margins. For one thing, he saw himself as the product of a different genealogy, a local history that conjoined the complexities of cubist space-making to the construction lineage of Coderch, Jujol and Catalan Modernisme. His trajectory is from the margin toward the centre, and his exuberant self-confidence the mirror image of Hejduk’s doubt. He was an architect of large ambitions, who never seemed to doubt that by some mixture of personal charisma and alchemy, the fluid space of his drawings could be translated into the hard material reality of a building. It’s not that he did not know or understand construction—in fact he had a very sophisticated grasp of building culture, which is in part why he never doubted that it would be possible to overcome the intractability of materials and the unwieldy apparatus of codes, conventions, clients, finance and bureaucracy that so often stand in the way of personal invention. The Scottish Parliament, realised after his death, is a disappointment precisely because it seems too close to the drawings, as if every mark on paper needed to be expressed literally, rather than be understood as a diagram of intention or affect.

The poet Frank O’Hara once wrote of Paul Klee that he was ‘fortunate in never having done a major work.’ It’s a notion that could apply to Hejduk, whose late drawings have been compared to Klee: ‘each individual thought as it comes to us trembling with wit and sensibility seems to be all of him.’[3] But not to Miralles, who, more than anything, wanted to produce major work (which is, in part, the problem with the Scottish Parliament). And so, of the two it is Miralles where there is a tragic sense of a career cut short. The work of the studio continues under the direction of Benedetta Tagliabue as Miralles Tagliabue/EMBTA, still propelled by the momentum of Miralles’ distinctive hand and the force of his personality. But it is also worth considering that Hejduk’s most significant work came early in his career, The Diamond Houses, the Wall Houses and the Foundation Building were all completed by the time he was 45.

To be an architect requires an odd mix of arrogance and humility. Arrogance to take responsibility for a large, complicated and expensive piece of work; humility to understand that architecture’s logic and consistency come not from an individual but from the shared knowledge of the discipline. Hejduk’s generation included figures such as Rossi, Stirling and Ungers, as well as his New York Five contemporaries. These architects shared an idea of the architect as a cultural figure, still in contact with the first generation of modern masters, confident in the capacity of architecture as architecture to make a difference in society at large. Hejduk understood that modernist aspiration as already compromised and he retreated to the margins; he felt his own sense of ‘untimeliness’ keenly.

Miralles began his work under the shadow of post-modernism and the critique of modernism’s totalizing project. His generation has witnessed a further erosion of architectural expertise and a dissolution of disciplinary boundaries. At a time when constraints are tighter, and the agency of the architect more limited, architecture is expected to function in other registers: politics, branding, commerce and media. Could he have survived the toxic culture of the star architect and internet saturation? Impossible to say, beyond observing that Miralles had the benefit of an enormous talent and a working base that was simultaneously margin and centre. But Miralles’ approach was his alone. To follow his path is to search for a singular, unrepeatable voice while still respecting the logic of the discipline; a difficult, if not impossible task today. The same might be said for Hejduk’s late work. Perhaps only in Hejduk’s early work is the balance between personal invention and disciplinary specificity—between the arrogance of the inventor and humility in front of history—so finely calibrated that the work survives to resonate in the present.

Notes

- John Hejduk, ‘Conversation Between John Hejduk and David Shapiro’, in A+U, No. 244 (1991:01), 59–75.

- See the interview in John Hejduk, Mask of Medusa: Works 1947–1983 (New York: Rizzoli International, 1985), 129.‘Wall: Do you feel that Frank Lloyd Wright completed his work? Hejduk: Yes. Wall: And Corbusier also? Hejduk: Yes, all those architects really completed their work. Wall: But you mentioned that Corbusier should have done a Diamond House. Hejduk: Yes, but they completed their work in a panoramic view. That’s what made them masters. I am like a fly that comes in and says ‘OK, here is one aspect that has been left out, yet which has great potentiality, it should be wrapped up.’

- Frank O’Hara, ‘Reviews and Previews,’ in Art News (March 1954).

With special thanks to: Princeton SoA—Kira McDonald, Exhibitions Manager; Monica Ponce de Leon, Dean; Bruce Liang, and the Princeton SoA Staff; Graham Foundation—Sarah Herda, Director, and Ava Barrett, Program Manager; and Vasily Chumakov for the digital image preparation.

*

Stan Allen is an architect, writer and educator. He served as Dean of the Princeton School of Architecture between 2002-2012, and is currently teaching at The Cooper Union and the Harvard GSD. His practice Stan Allen Architect has realised buildings and urban projects in the United States, South America and Asia, and more recently, a series of houses and artist studios in New York’s Hudson River Valley.