All back to front: D’Aviler’s Cours D’Architecture

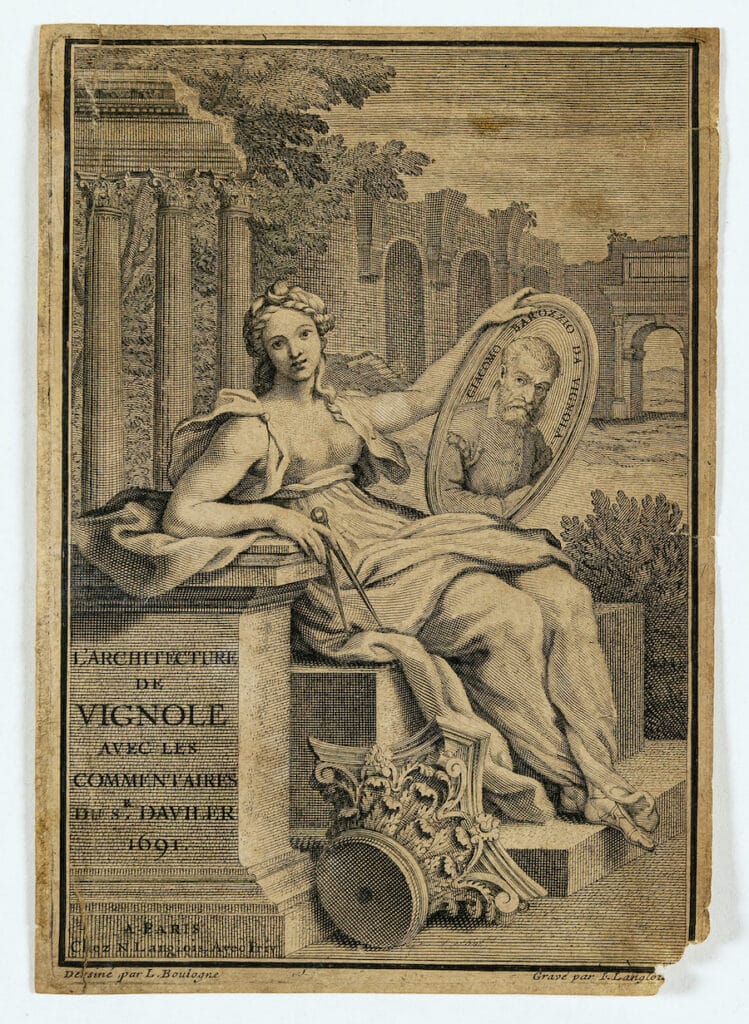

In Louis de Boulogne’s drawing, now in the Drawing Matter collection, Architecture appears as a young woman. She sits leaning on an altar with a Corinthian capital at her feet, compasses in one hand and a portrait of Vignola in the other. Behind her are the ruins of Rome.

It is the preparatory drawing for an engraving by Jean Langlois, the frontispiece to Augustin-Charles D’Aviler’s Cours d’Architecture. Louis de Boulogne was the King’s Premier peintre, but he was also D’Aviler’s close friend and the architect has corrected the painter’s perspective at the foot of the altar.

Because the printed image will mirror the engraved copperplate, Boulogne’s figure of Architecture is reversed. The red chalk which still covers the back of the drawing enabled the engraver to transfer her image onto a thin coat of white wax covering the copperplate, firmly following the lines of the drawing with a stylus. Lettering, again in reverse, was added to the copperplate at proof stage, so in the final print the altar is engraved with the original title of the work for which the King had granted D’Aviler a privilege, a precursor to copyright, in April 1691: L’Architecture de Vignole aves les Commentaries de Sr. Daviler 1691.

D’Aviler had prepared a translation and commentary on Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola’s 1562 book The Five Orders of Architecture, almost a decade earlier, in 1683. Over the next five years, while working unhappily in Jules-Hardouin Mansart’s office on designs like those for a château in the Drawing Matter Collection, he spent his free time refining the text of his Vignole and preparing the drawings for its plates.

By 1689, the book was being printed and this may provide a date for Boulogne’s frontispiece, which, until now, was the only drawing for the work known to survive. It certainly predates the change of title to Cours d’Architecture, qui comprend Les Ordres de Vignole – the title with which it was published in May 1691.

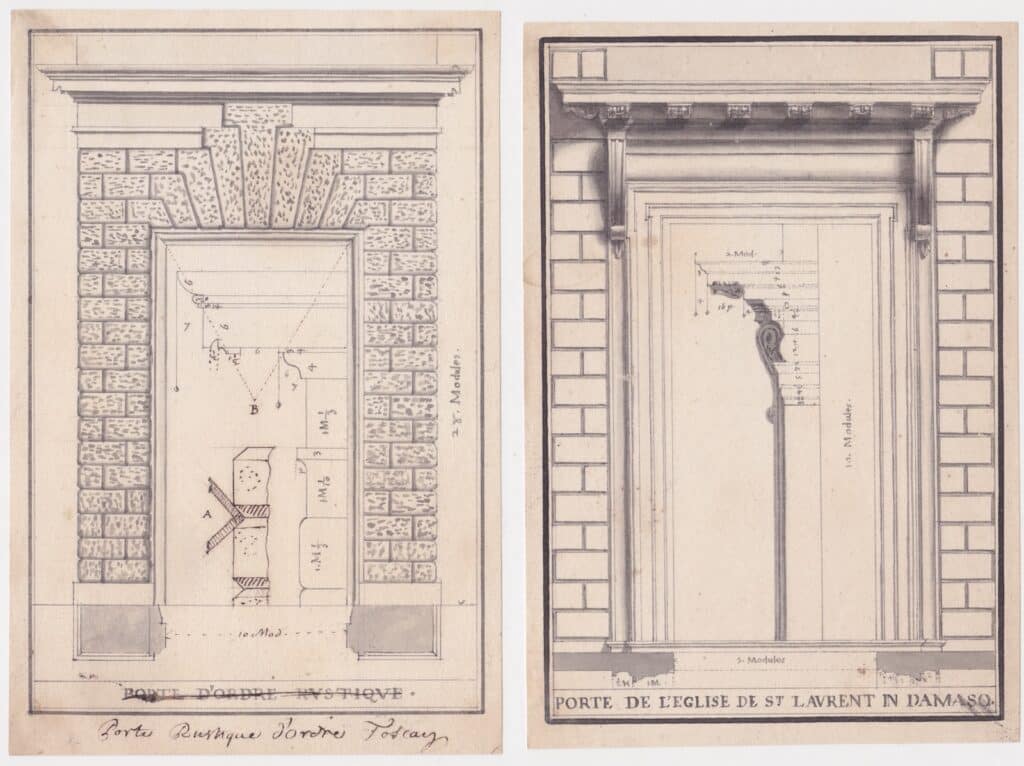

Recently a group of 11 drawings by D’Aviler have emerged: seven are elaborate designs for lambris or panelling, which were not engraved, but four are designs for plates in the first edition of the Cours. They illustrate the process of producing a seventeenth century architectural book. The four drawings are the same size as the engraved plates. Like the frontispiece, they are reversed in the engravings. The first is for Plate 44, where, interestingly, D’Aviler has crossed out the original title, Porte d’Ordre Rustique, and written Porte Rustique d’Ordre Toscan. The correction is followed in the published engraving. No red chalk is found on the back of this drawing nor on the companion design for Plate 47, the Porte de l’Eglise de St Laurent in Damaso, suggesting the engraver used an additional chalked sheet, like a carbon paper, beneath the drawings to transfer the design to the copperplate.

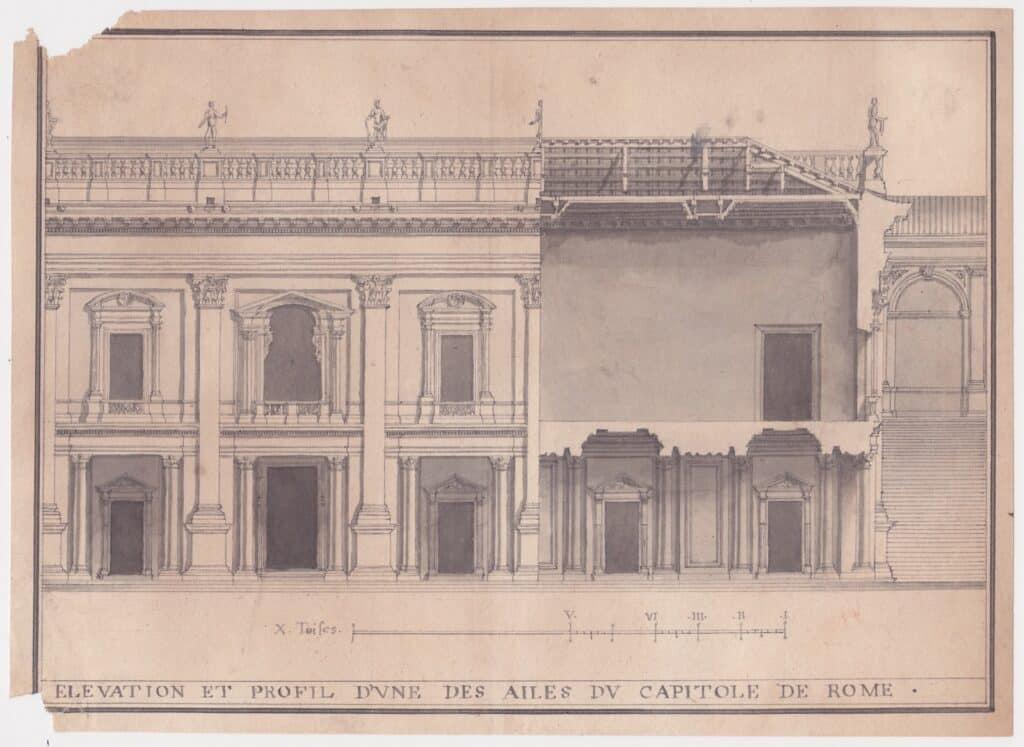

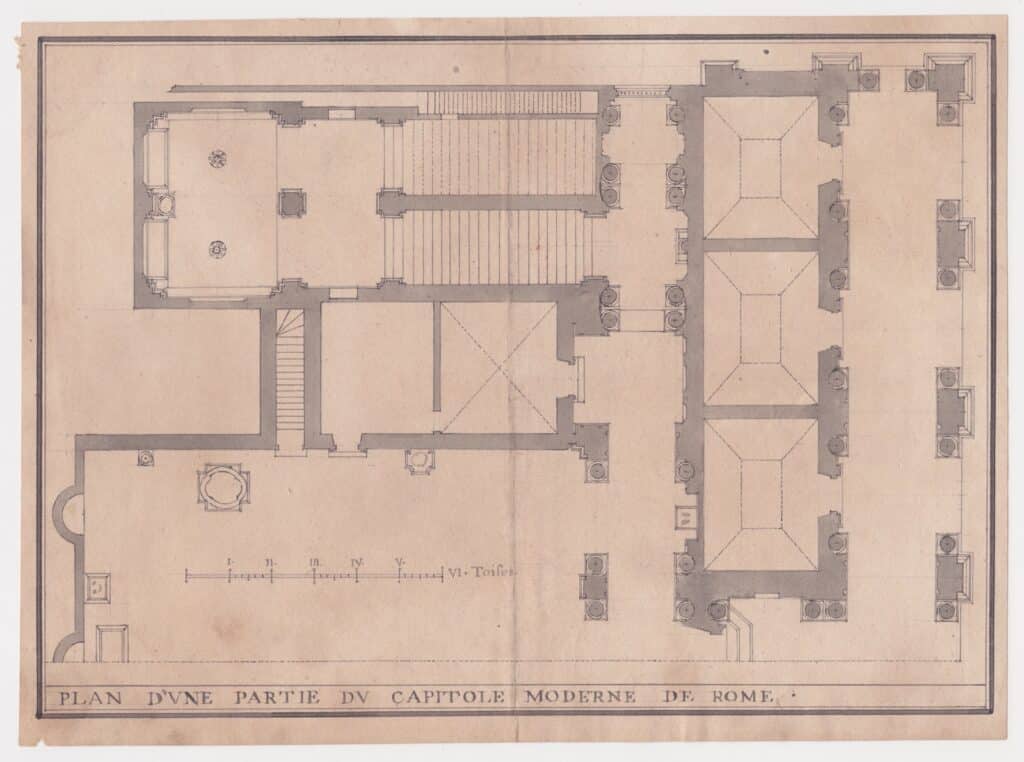

These two drawings closely follow engravings in earlier editions of Vignola, and contrast sharply with the extraordinarily delicate drawings for the Elevation et Profil d’une des Ailes Du Capitol de Rome, Plate 82, and the corresponding Plan, Plate 81. For both of these larger folding plates the engraver, Pierre Lepautre, has used red chalk to transfer the fine detail of Michelangelo’s architecture to the plate.

As D’Aviler’s book went through the printers it grew wings – more large folding plates which he inserted at the last minute, messing up his careful numbering of plates but including plans of gardens, palaces and details of ironwork. What had started as an attractive and accessible guide to the Orders, intended to inform clients, artisans and fellow architects, now became a platform for D’Aviler’s own architectural ambitions. Further plates were engraved but there was no room in the first edition or a second in 1694 and so, alongside them, D’Aviler prepared drawings for an enlarged edition. He would never see it.

D’Aviler’s death at the age of 47 in 1701 was followed by that of his publisher, Nicholas Langlois, in 1703. Work on the new edition was continued by his son Nicholas Langlois II, who had ‘acquired a very large quantity of new Drawings, & Explanations, both from the Author and from several other excellent Architects, Painters & Draftsmen… with which to increase & embellish this Work.’

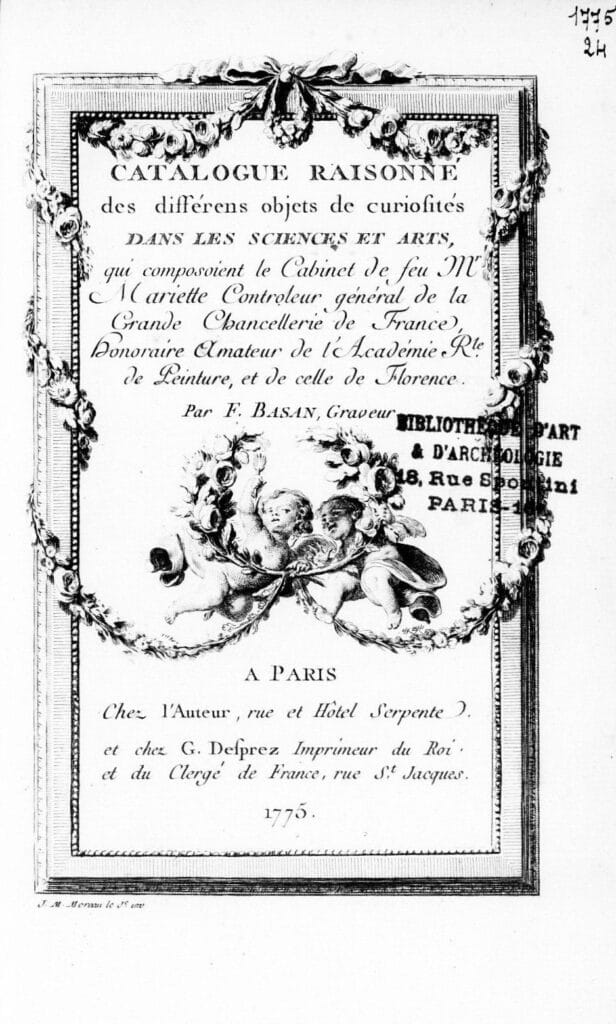

The death of the younger Langlois and the sale of the business to a cousin, Jean Mariette, delayed the larger edition of the Cours until 1710. Mariette’s son, Pierre-Jean, brought it up to date with additional plates by distinguished architects in 1738 and 1750, before he sold up to concentrate on writing and collecting.

Mariette admired D’Aviler and compiled his biography. He mounted D’Aviler’s designs, Boulogne’s frontispiece and other architects’ drawings for the Cours on sheets in a portfolio, which joined more than 100 others, to make up one of history’s greatest collections of drawings.

‘A Portfolio, containing 90 architectural drawings, most of which were used to engrave the Vignol in 4° plates. They are made with care & precision in Indian ink, by different Masters’ was Lot 1431 in the posthumous sale of Mariette’s 9400 prints and drawings on 15 November 1775.

It was bought by the publisher Pierre-Michel Avaulez who perhaps intended to re-engrave the drawings for a new edition of Vignola, though in the end the Nouveau Livre … par… Vignole that Le Père and Avaulez published a year later simply reproduced D’Aviler’s engravings in reverse.

The whereabouts of the drawings in Mariette’s portfolio over the next century is unknown but since Louis de Boulogne’s frontispiece and the group of drawings for the Cours by D’Aviler both turned up on the Paris art market around the year 2000, one may hope that more will surface.