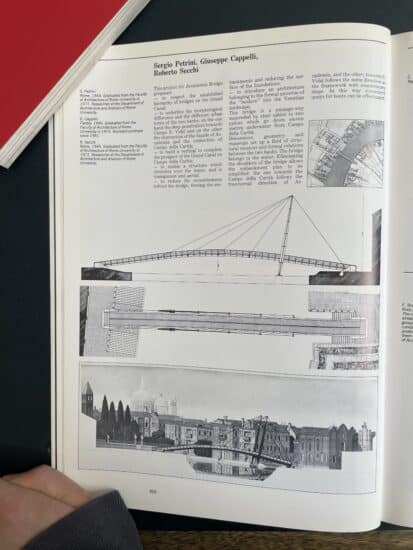

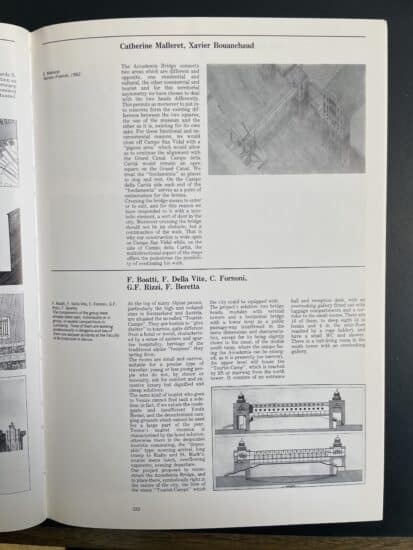

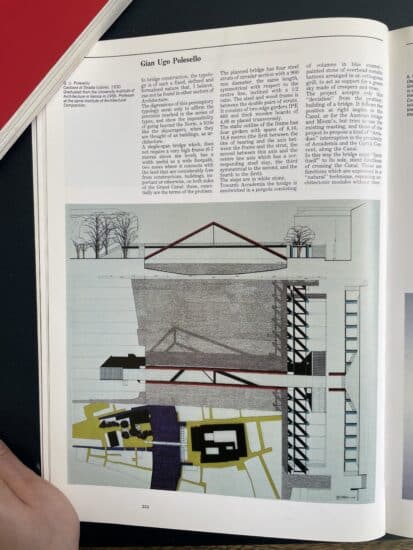

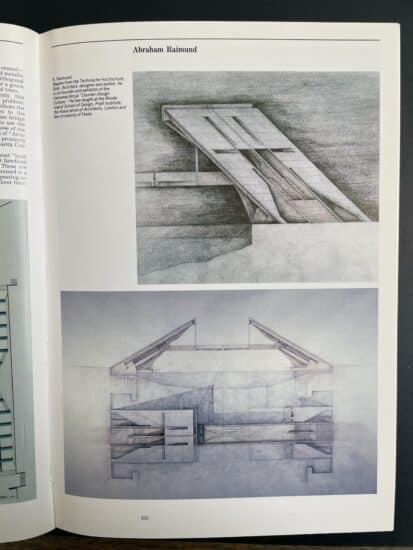

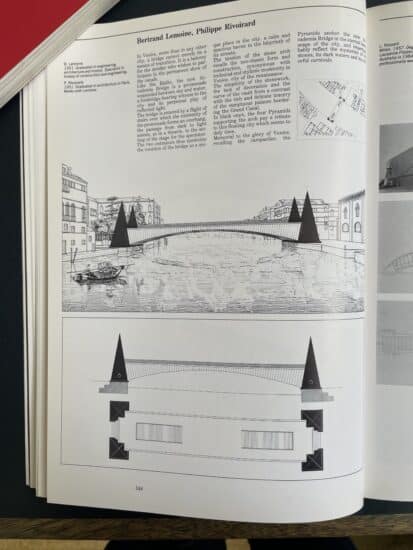

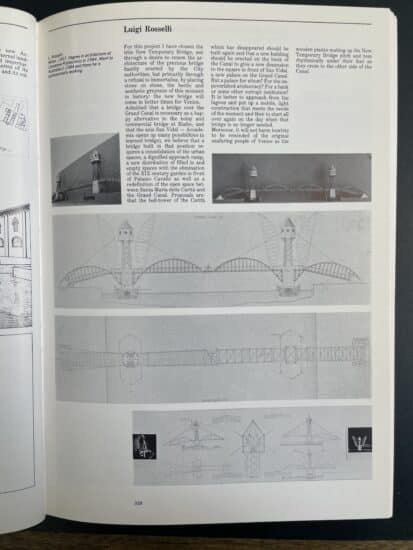

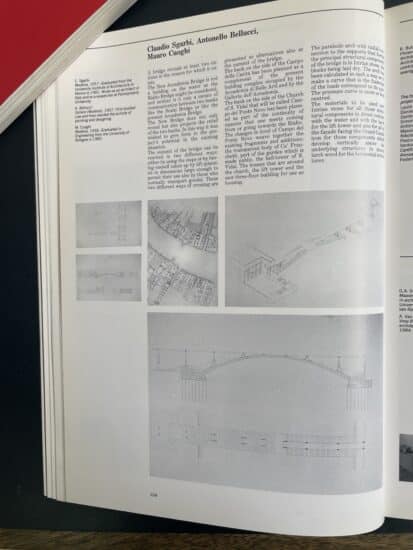

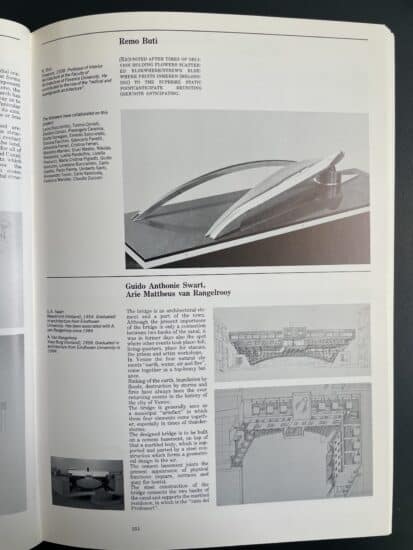

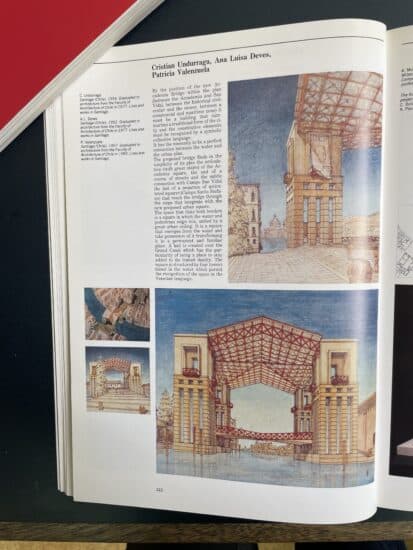

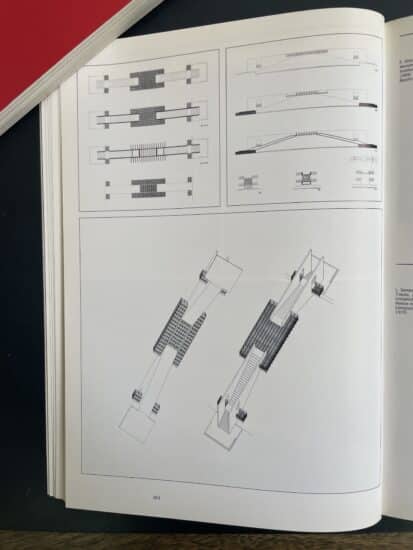

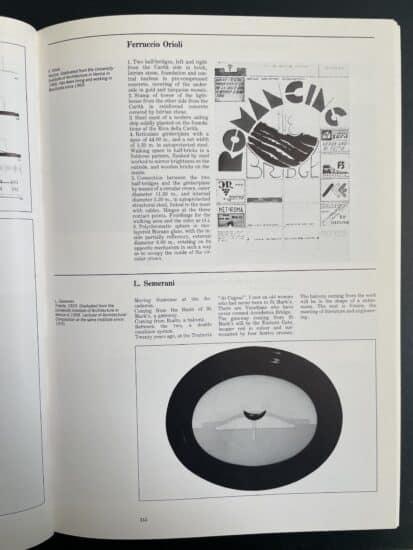

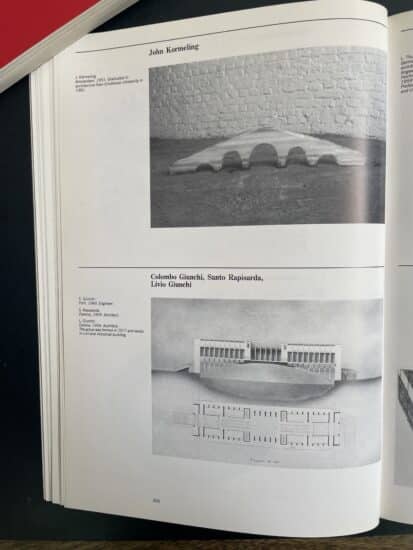

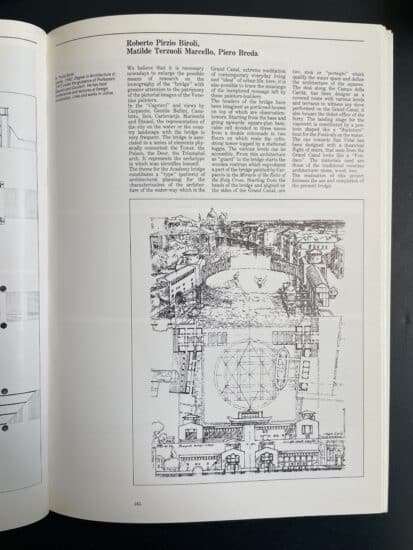

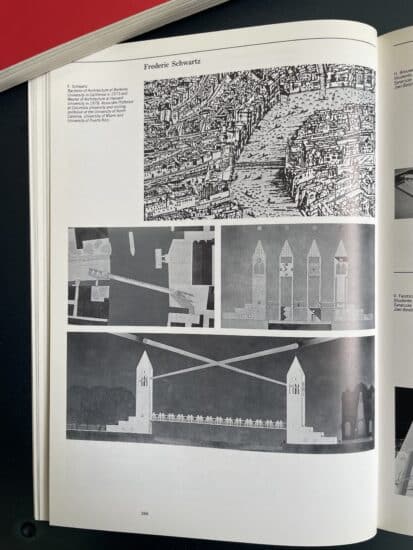

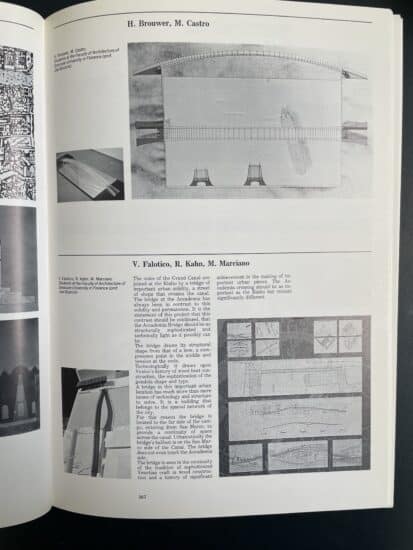

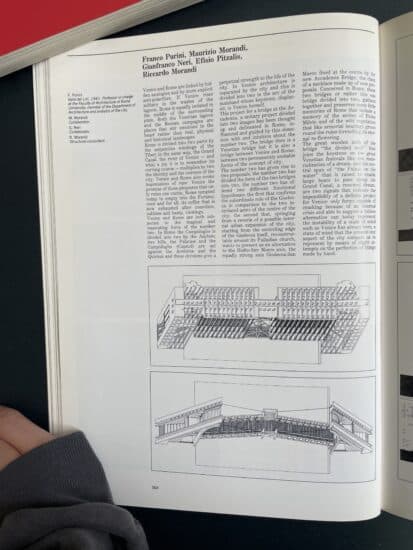

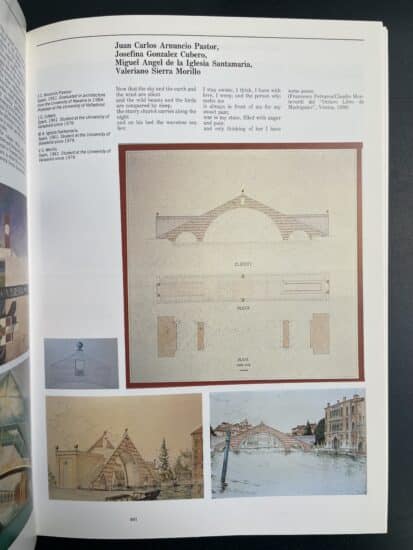

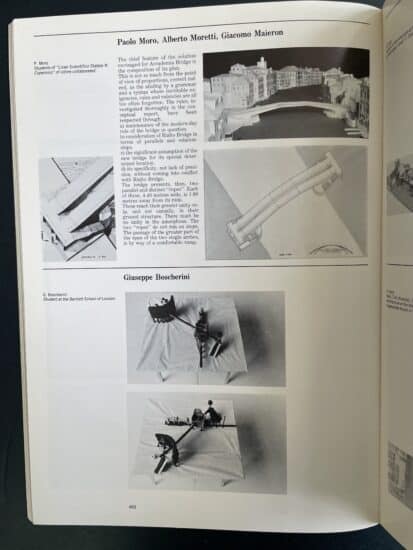

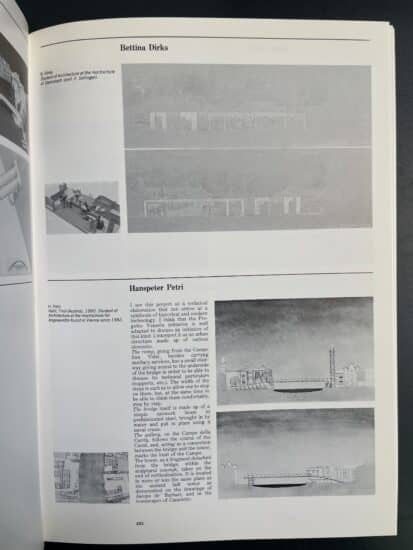

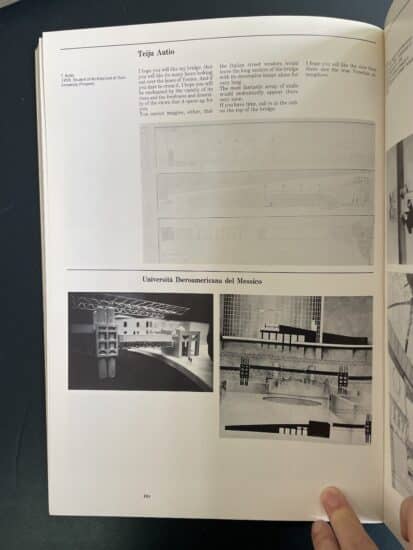

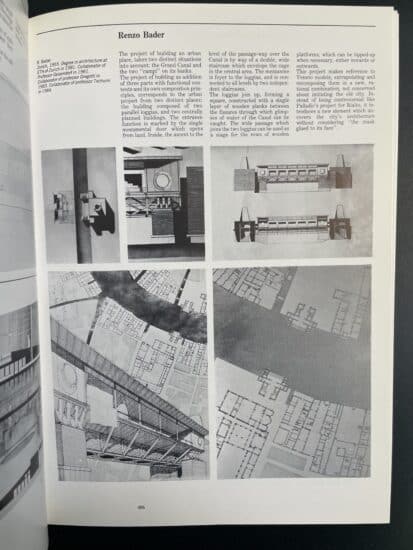

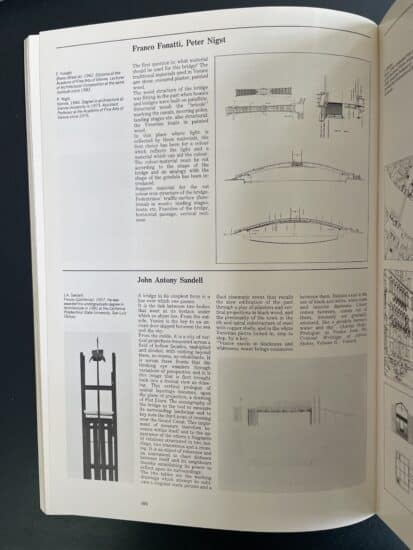

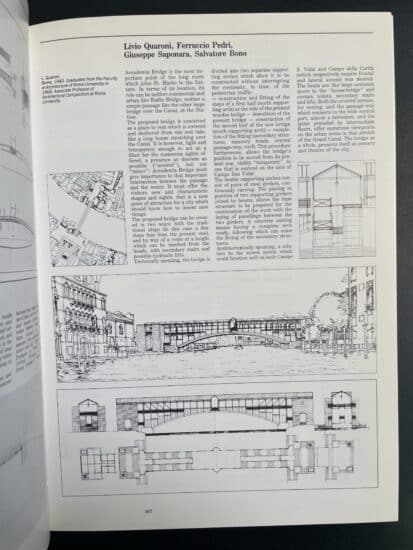

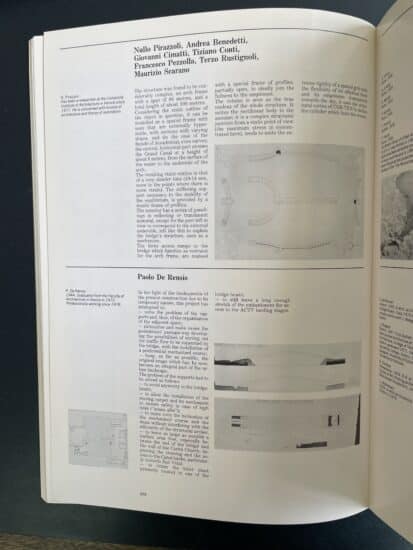

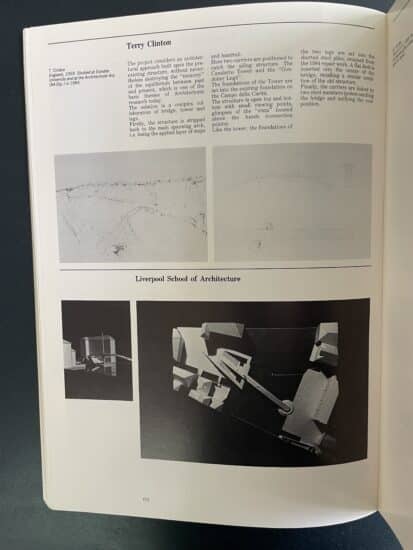

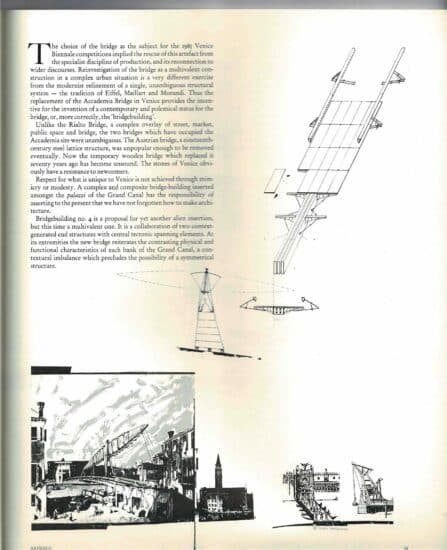

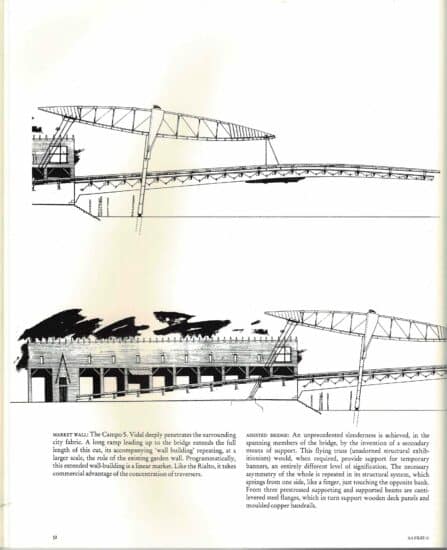

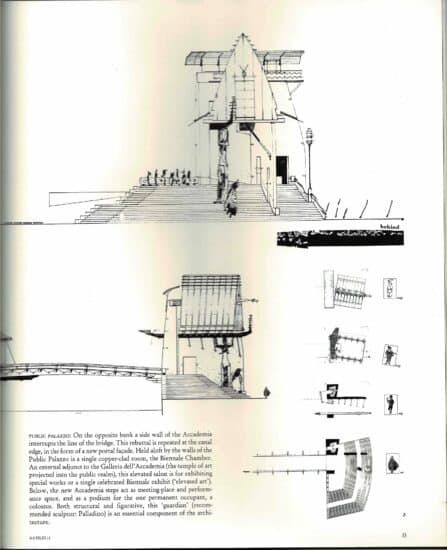

Accademia Bridge Proposals: Venice Biennale 1985

– Editors

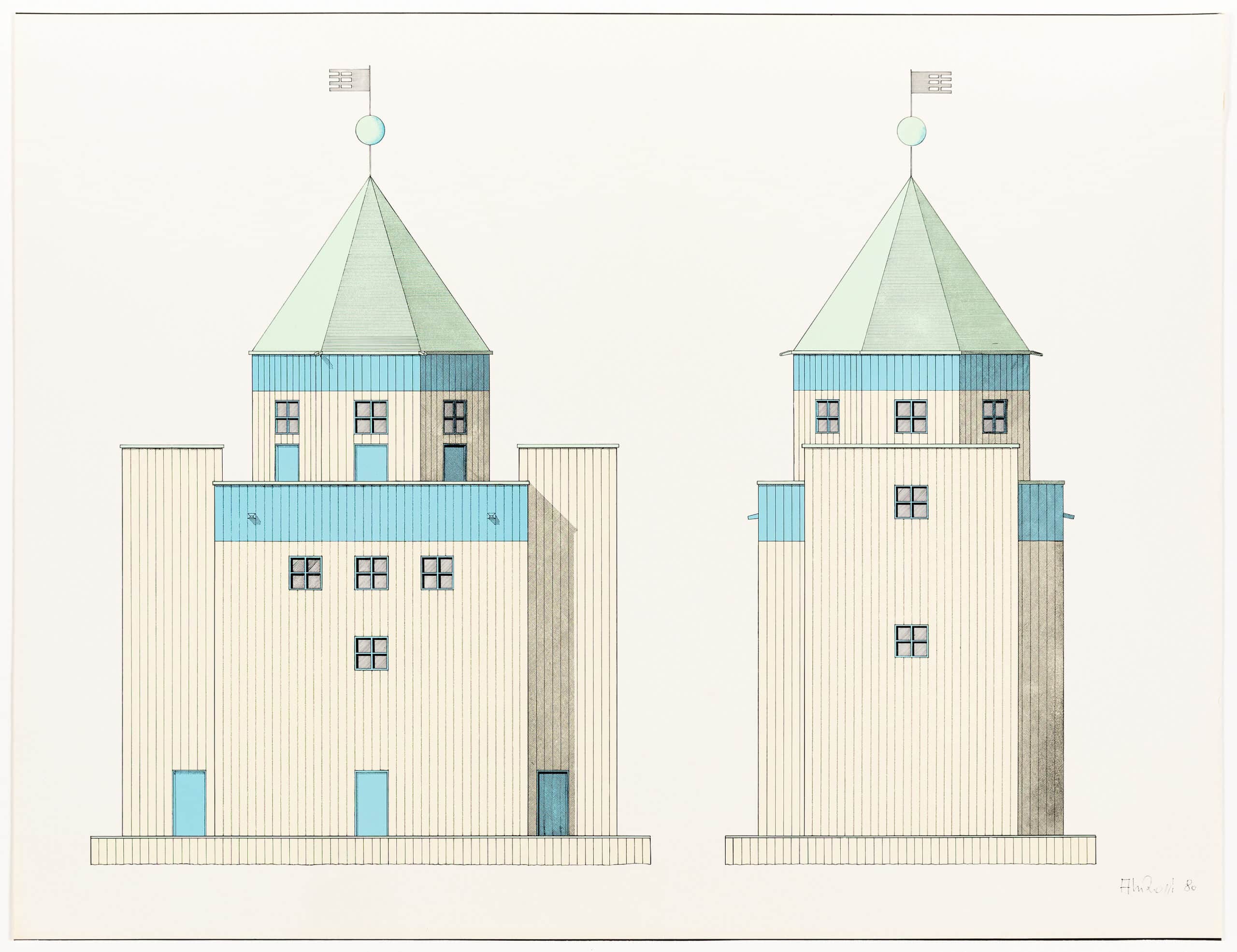

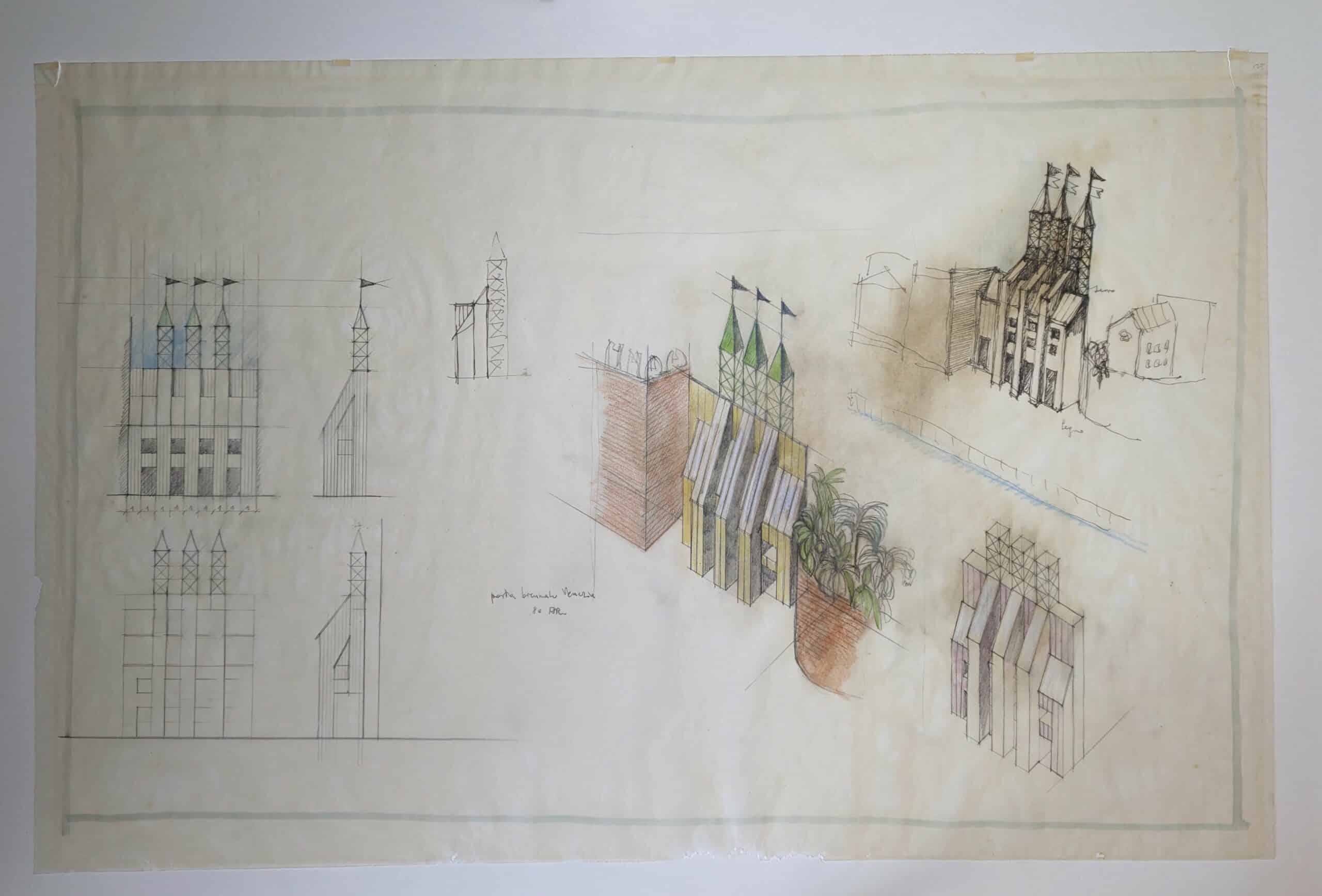

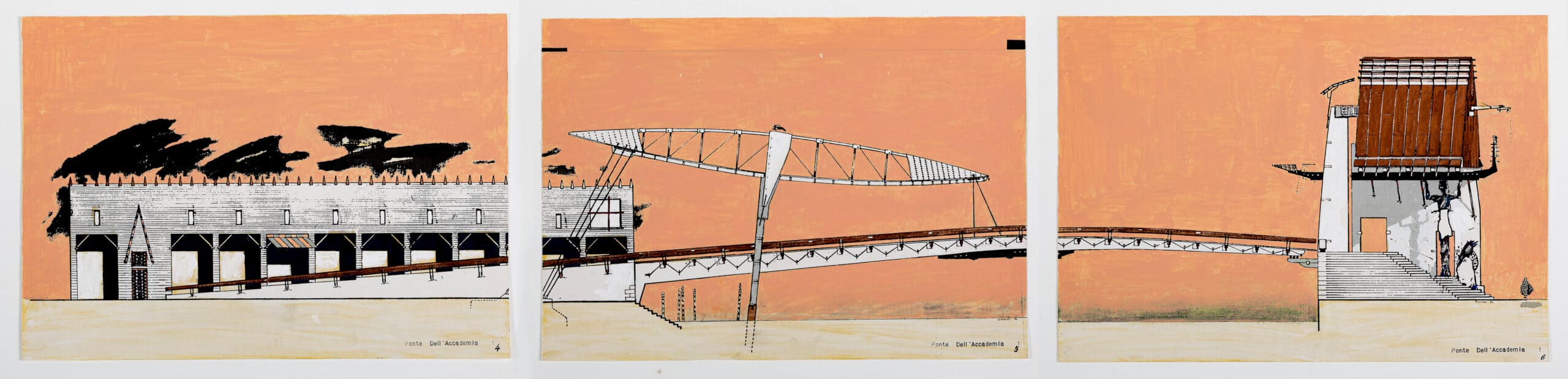

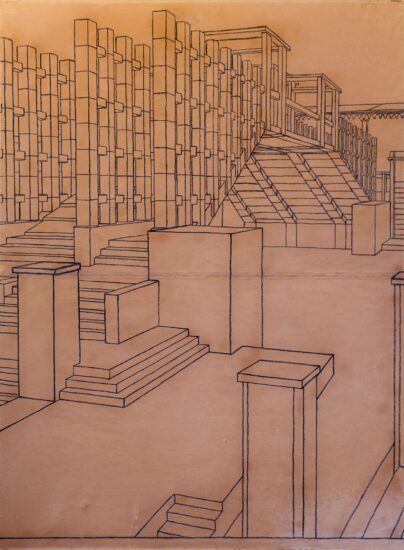

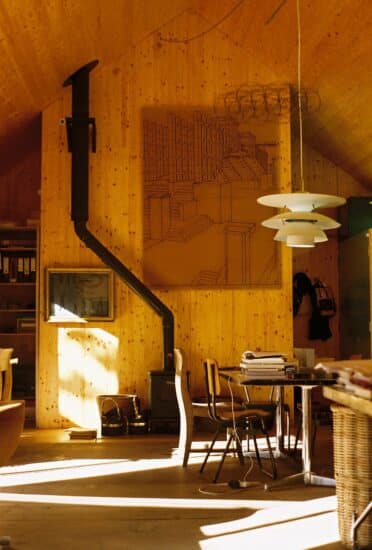

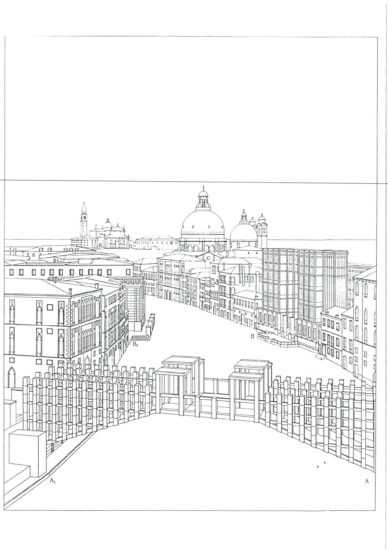

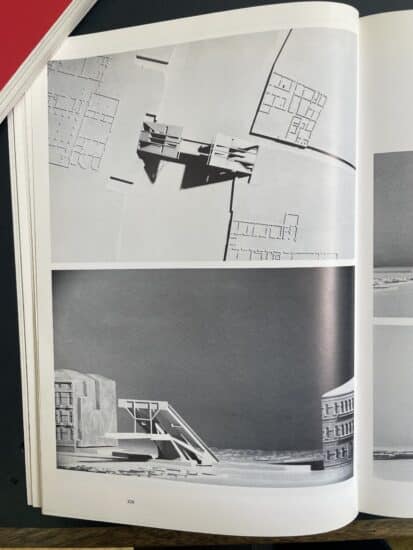

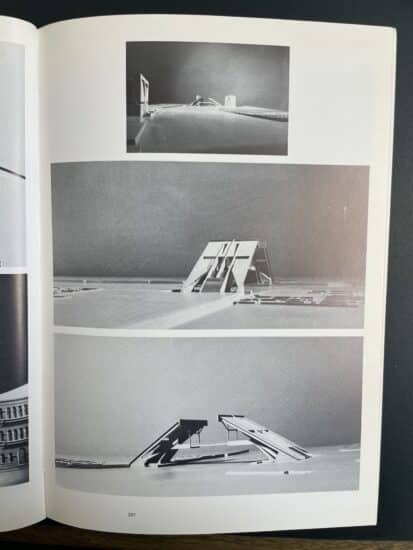

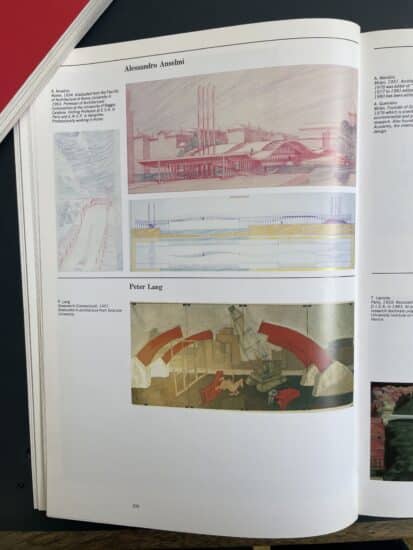

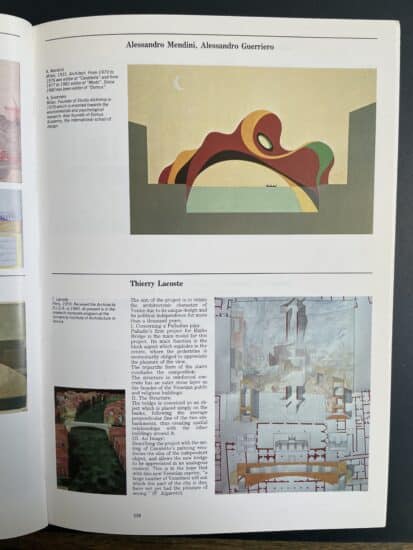

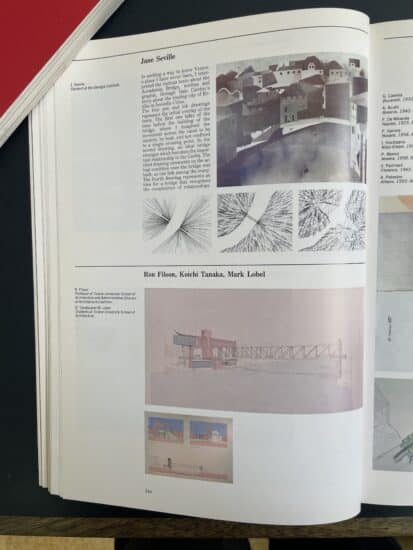

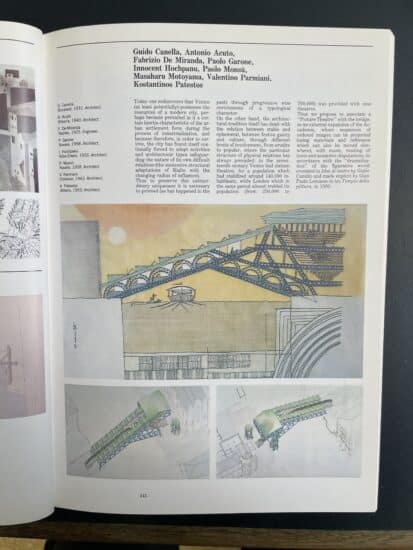

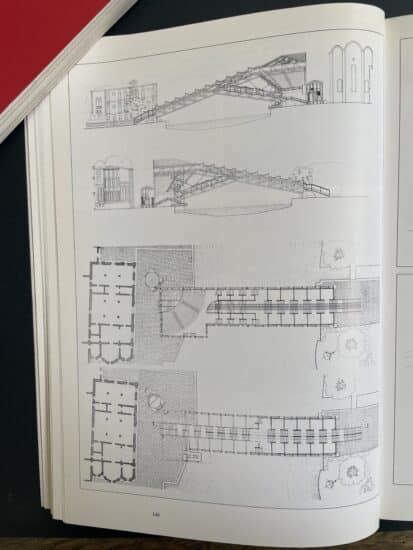

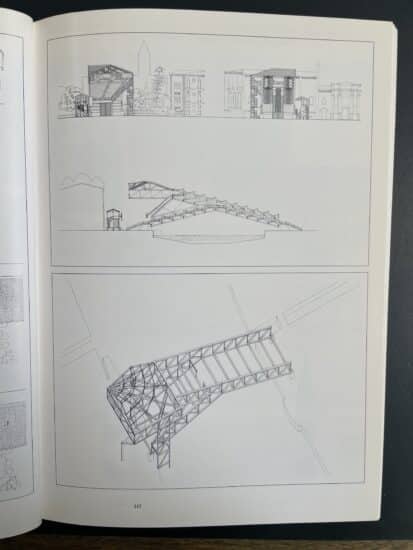

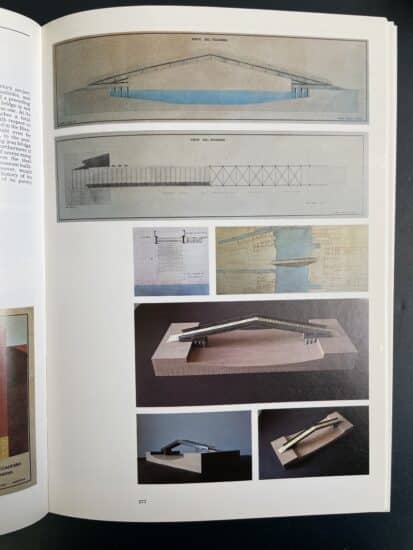

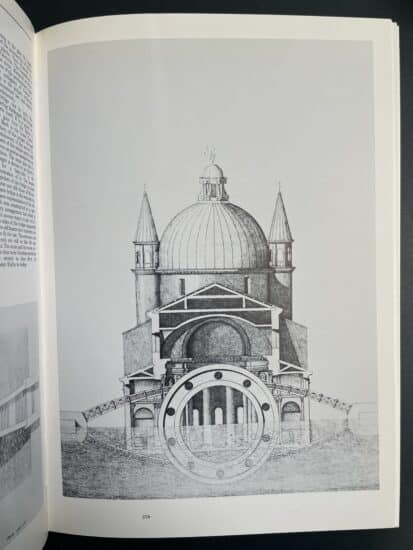

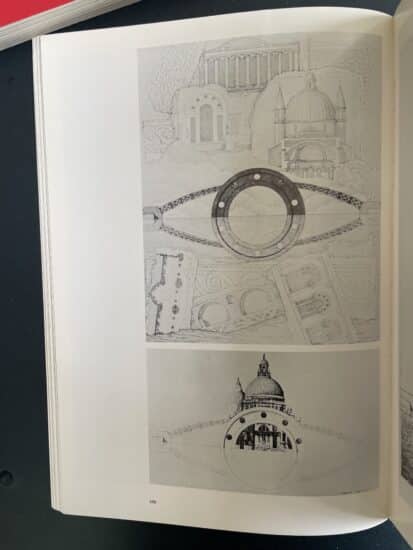

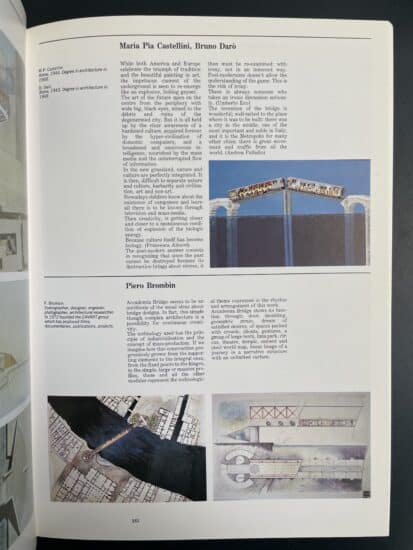

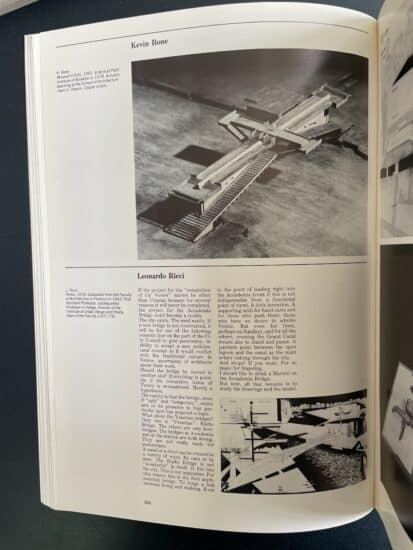

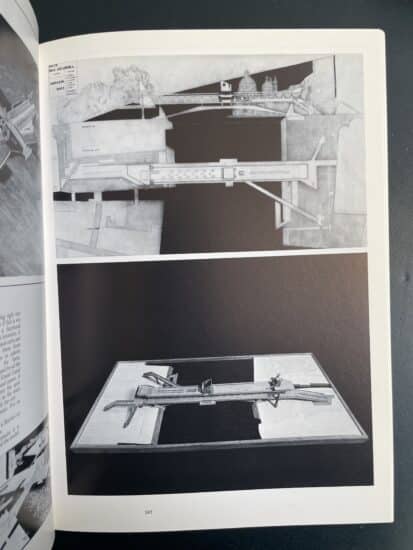

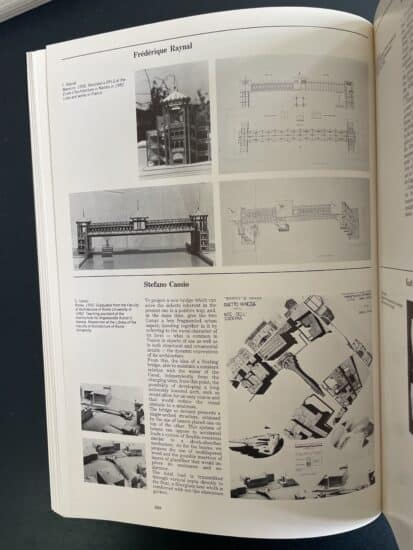

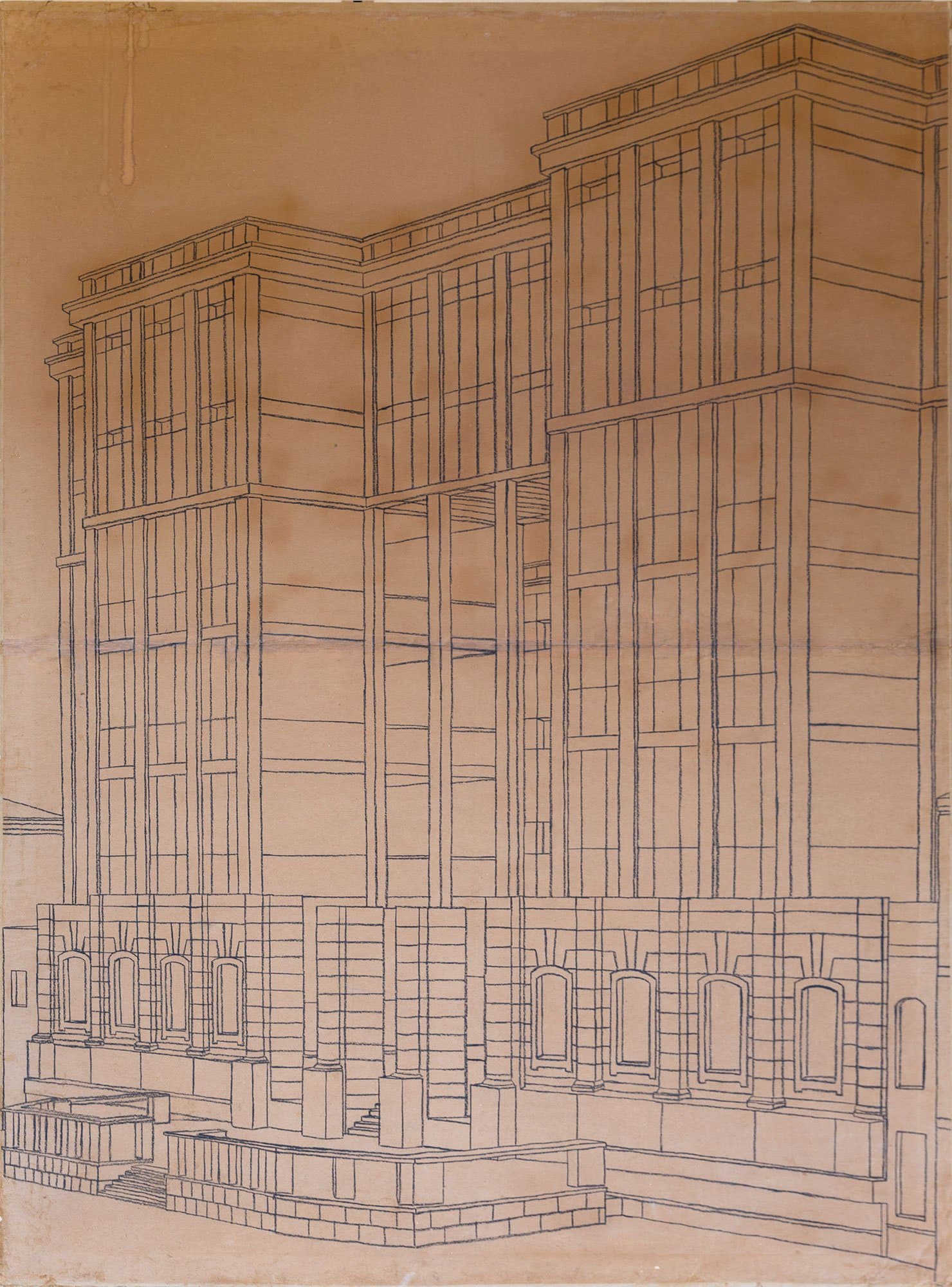

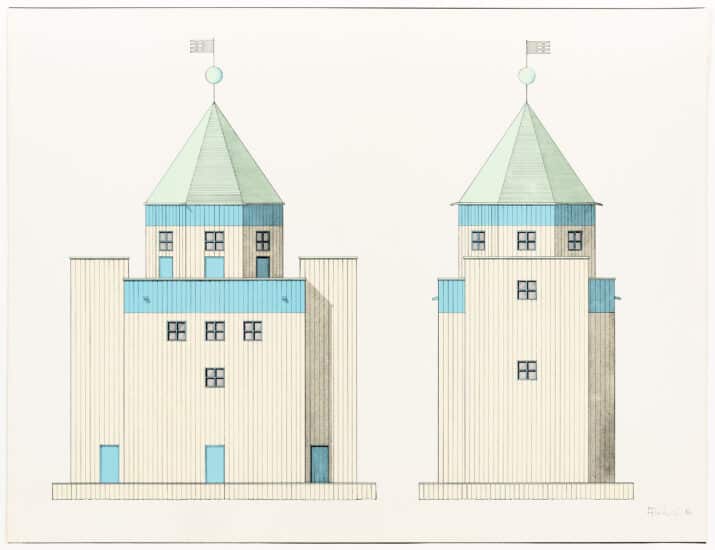

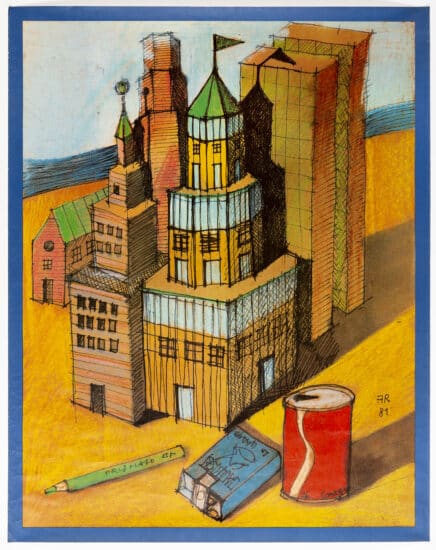

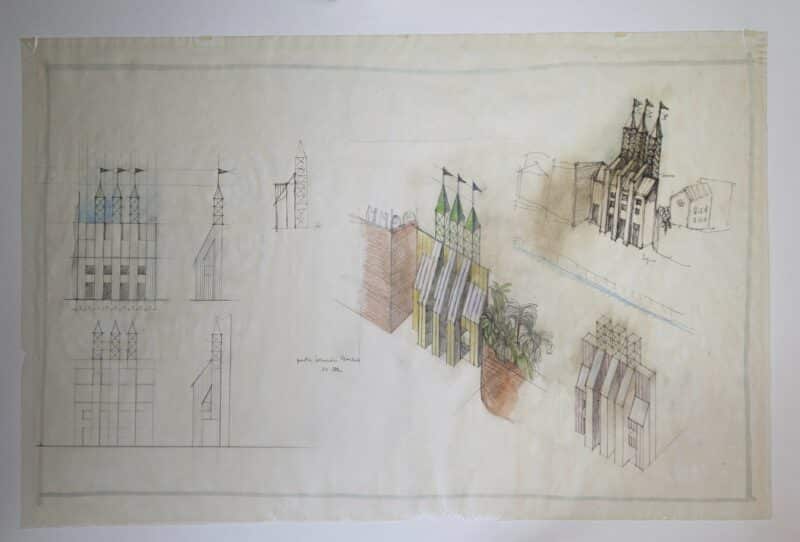

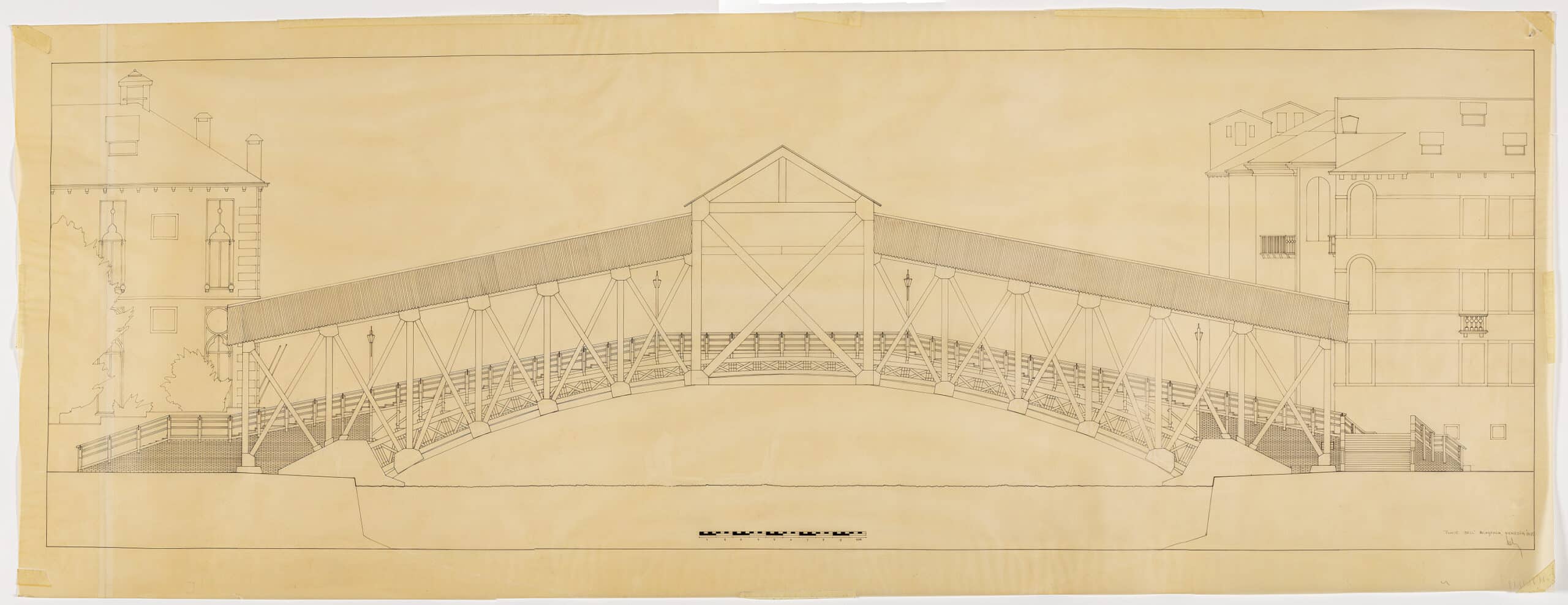

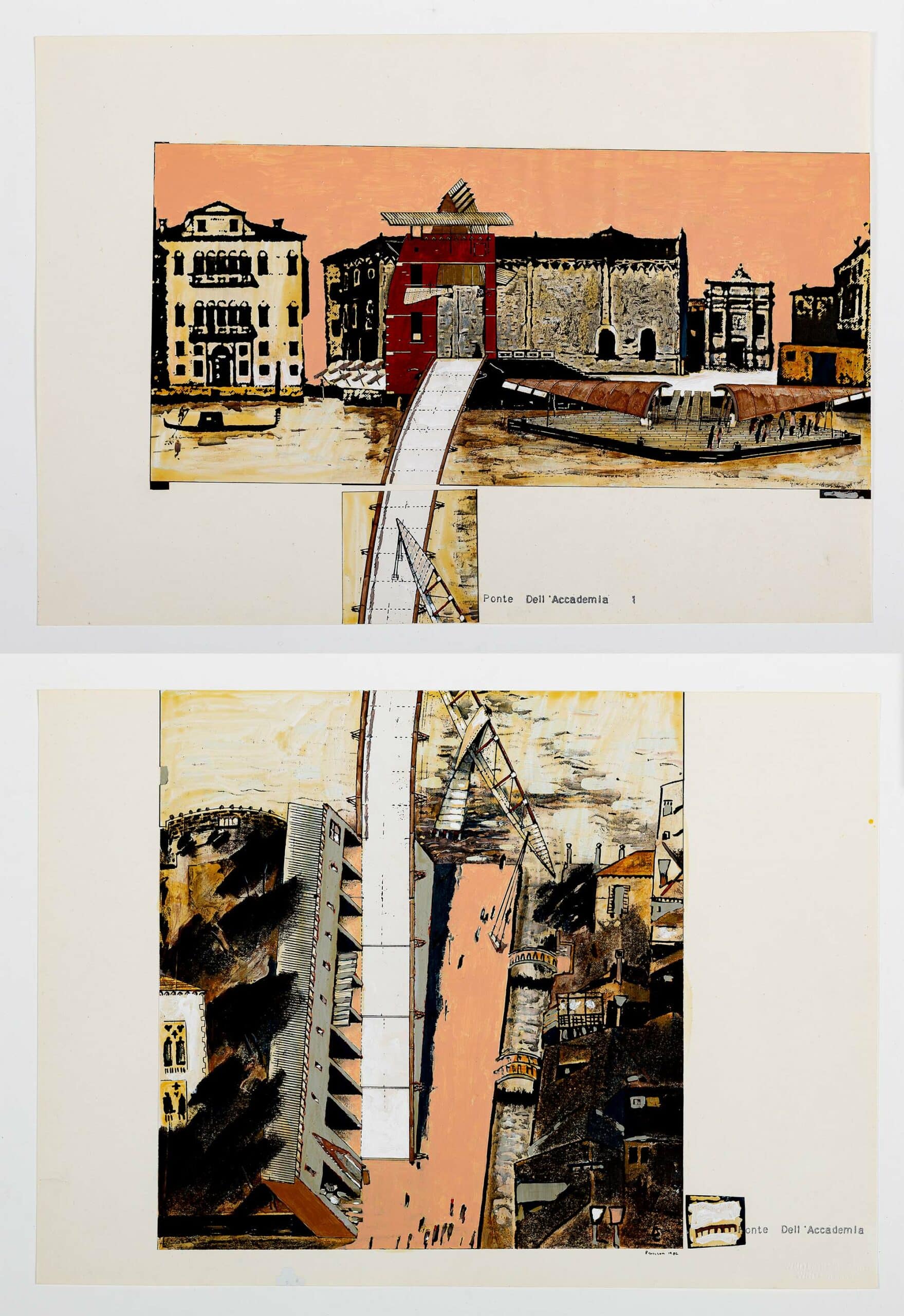

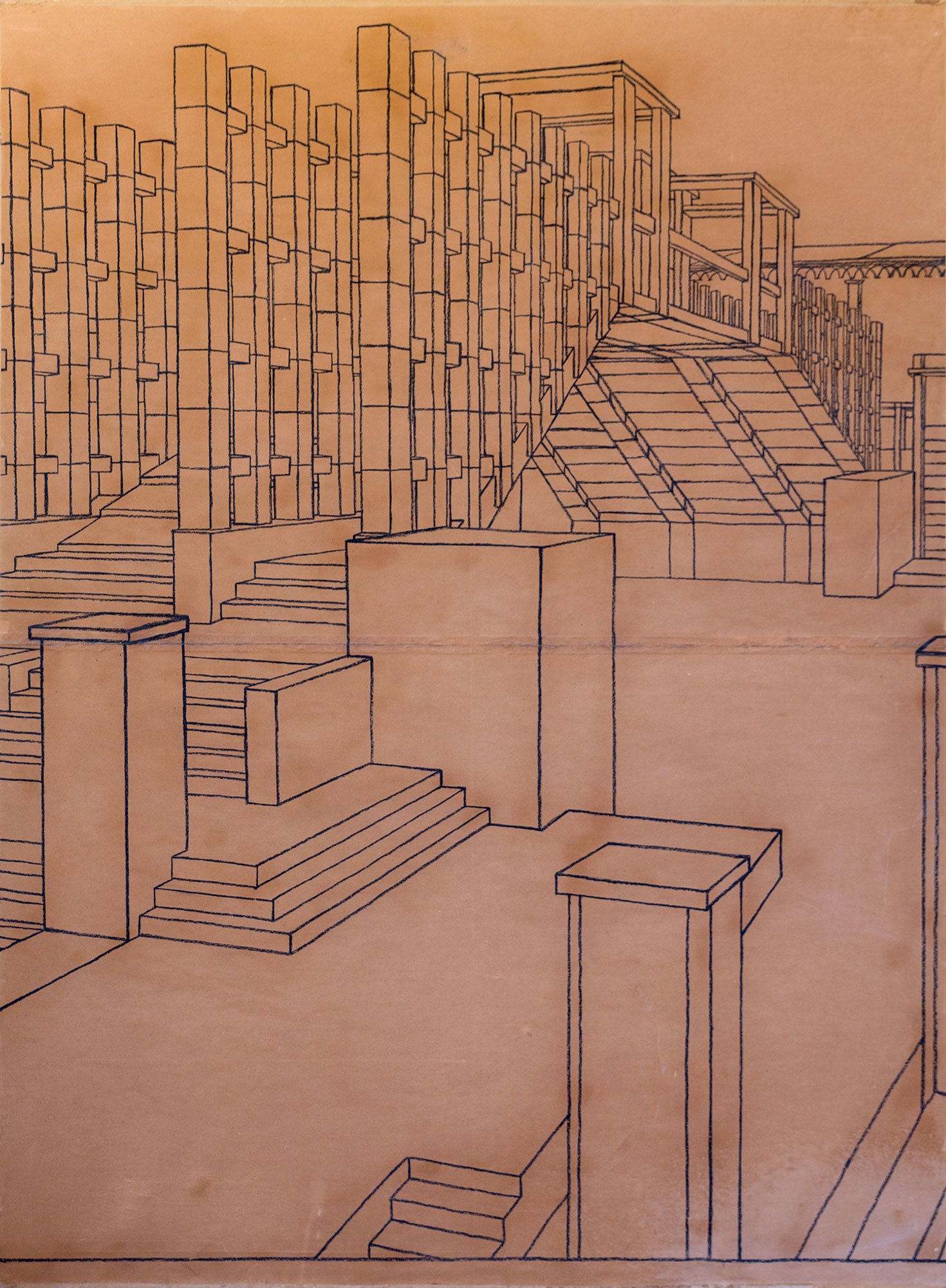

This project scrapbook was prompted by Drawing Matter’s recent acquisition of drawings by Peter Wilson and Luc Deleu, made in response to Aldo Rossi’s ‘Progetto Venezia’ brief for the 1985 Venice Biennale, which invited proposals for a new Accademia Bridge to replace the wooden one constructed in the 1930s. Wilson and Deleu’s projects join two imposing drawings—each about 2 x 1.5m—by Dario Passi for the same project, one of which now hangs in Drawing Matter’s office.

Francesco Dal Co’s introduction to the Accademia Bridge Competition in the Catalogue of the Biennale di Venezia 1985

It has often been remarked that Venice’s traffic network operates on two levels. In fact the city boat and pedestrian routes are determined by the diversity of the natural elements: on one hand the waterways and, on the other,... Continue Reading

Francesco Dal Co’s introduction to the Accademia Bridge Competition in the Catalogue of the Biennale di Venezia 1985

It has often been remarked that Venice’s traffic network operates on two levels. In fact the city boat and pedestrian routes are determined by the diversity of the natural elements: on one hand the waterways and, on the other, the network of streets. The bridges are the practical link between the two but they also ensure the physical independence of the two systems.

It is not merely a coincidence that Venice’s most important bridges were built because of exceptional circumstances in the given historical moment, or in response to particularly pressing social-economic needs. This has determined the definition of the special nature of Venetian bridges. They have the special feature of often assuming strong symbolic meanings rather than being just representative of the integration processes of urban functions. From this point of view, the Rialto bridge is an emblematic example. With its plurifunctional structure and particular shape, the bridge fulfills the symbolic role of joining the two poles of Venetian life, by linking the area of St. Mark’s, the appointed seat of institutional power which upholds the destiny of the Republic, to the Rialto area, the seat of trade and economic power which ensures the prosperity of the city.

However it would be wrong to confuse the meaning of the bridges which ensure the continuity of Venice’s street network with that of the bridges built just to cross the Grand Canal. While the former guarantee the logical independence of the traffic network in the heart of the city, the latter, pictured only to unite the two banks of the Grand Canal in strategic points, exist for particular reasons and have meanings whose diversity is bound to come under comparison. First of all, any hypothesis formulated for the construction of new bridges over the Grand Canal, involves an implicit comparison with the pre-existent Rialto bridge. Moreover, any further bridge over Venice’s principal waterway endangers the balance which ensures the independence and integration of the two main traffic networks: the canal network, which is predominant because it is based on the constant dividing line represented by the Grand Canal, and the pedestrian one, which is independently integrated into the introvertive and insular succession of streets and squares. As a basis for an analysis of the problems involved in replanning the Accademia bridge, a historical reconstruction seems necessary – starting with the first decades of the XIX century and the decision to make a direct connection between the two banks of the Grand Canal in front of the Church of the Carità, up to the substitution of the manufactured bridge by the provisional one in 1932 (while waiting for the results of the competition for a permanent one).

The projects proposed for the bridge in the first decades of the XIX century are inevitably of great interest to the contemporary architect, as they span the full range of the technical/urbanistic hypotheses that were current at the time. A more thorough view of the significant urbanistic theories presented by the Accademia Bridge as well as of the technical problems implicit in the project,—the relevant pages of G.D.

Romanelli’s, Venezia Ottocento—should clarify the situation. In fact, these pages contain the best historical investigations on the subject available today.

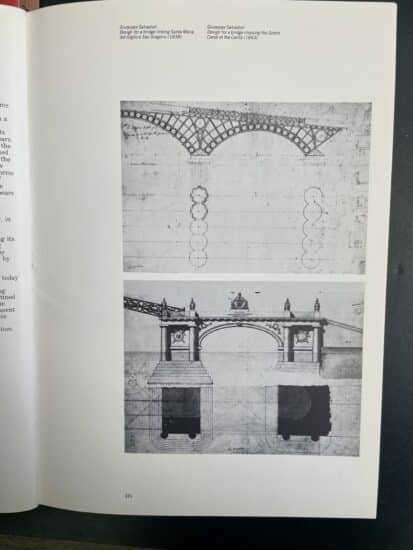

‘On the occasion of the Austrian Emperor’s official visit to Venice in 1938, Giuseppe Salvadori presented to Savrono two projects that were destined to have great success, (…) and a bridge (the second project) over the Grand Canal between S. Maria del Giglio and S. Gregorio’.

This was the first complete plan for the future Accademia Bridge. However, the project was delayed for more than ten years and was only completed in 1854, becoming one of the most exemplary models of urbanistic operation during the years of Austrian control.

The need for a second bridge over the Grand Canal, in addition to that at Rialto, in the area of the x-convent of the Carità (now the Fine Arts Academy) had already been affirmed by Casarini in 1822, and again in ’23 in a proposal by Salvadori. Salvadori later prepared the project on the occasion of Ferdinand I of Austria’s visit, but with a different location than the one proposed by Casarini: he favored a connection between Campo S. Maria del Giglio and the area opposite the small houses next to S. Gregorio in the proximity of the ferry.

But at this point the project had not run full circle; it had not matured in the wider community neither with respect to who would be able to undertake it, nor in researching its possible advantages or the immediate economic effects it would have on the community.

Salvadori’s project in ’38 actually succeeded in anticipating and stimulating an entrepreneurial response apart from that of the government.

In a ritual that would be endlessly repeated in analogous situations, the necessity for a bridge over the Grand Canal only became recognised and approved when some important people—best if thev were property owners—took up their pens and drew up a petition directed to the administration. In the summer of 1843 some property owners in the Dorsoduro quarter announced the ‘need to unite the S. Marco District with that of Dorsoduro by building a bridge over the Grand Canal’. The conviction that this connection would be extremely useful was so strong and deeply felt by these same citizens ‘that they made it clear in their petition that they would temporarily be willing to support a larger than normal income-tax to get it built’. The justifications for the immediate need for this access were effectively collected and interpreted by the city councillor, Count Dona, in his report to the city government on August 31, 1843:

‘The quarter of Dorsoduro contains buildings which are remarkable as well as of great public interest: for example the huge Barracks for the Garrison Troops, the Customs House and the Emporiums that are so important for the Treasury, a Seminar which provides priests for the Church, a Royal Academy of Art where one studies so as not to risk losing the support of the Highest Sovereign, the School of Charity which testifies to the philanthropy of our era, the Orphanages under the auspices of the Religious Institutions. All are unfortunately cut off from the S. Marco District and its environs and thus from the Civic Center; for one cannot arrive there without crossing the Grand Canal, or otherwise making the long trip around by way of the Rialto Bridge for those who can not afford to take a boat every time. The sad effect of their isolation can be seen in the steady deterioration of the rental buildings as well as those of the inhabitants and consequently the shops (.), their up-keep is constantly put off in preference to those in the S. Marco Quarter because they can not support them on the little income they earn’. The property owners along with Donà were among the first to recognise the most immediate and pressing concerns: a larger public funding expenditure would allow (with no particular negative effects on the property) the city to undertake a more important re-evaluation of a great urban area.

On the other hand, there seems to have been concern over the fact that the Emporiums and the warehouses near the Dogana della Salute would have the advantage of, one, being close to the customs offices, and two, of now being more easily accessible for large barges to reach both through the first stretch of the Grand Canal and a stretch of the Giudecca Canal. It was actually this issue that was to cause most of the negative reactions, but they were later rejected by various groups once the decision was taken to build a permanent bridge that would impede navigation in the part of the Grand Canal between the new bridge and the Rialto. Many property owners located in this zone lamented that their business would be damaged when the tall-masted ships and the steamboats were barred from that part of the canal. Many recognised these concerns, and one can even see that their position was stronger and that they were going to suffer more immediate consequences than their opponents.

When one refers to the written ‘declarations’ by those for and against this solution it is not clear why one party won over the other.

Above all, it is important to keep in mind the main issue underlying Venetian economy and urbanism during the 1840s: the Venice-Mestre railway bridge across the lagoon and the immediate effects it produced. The main axis of the city was thrown completely off balance by moving the centre of interest from the Basin of St. Mark’s to Cannaregio on the north. The S. Marco – Dorsoduro axis (with its fulerus at the Carità Bridge) would offer an alternative or a resistance to this imbalance, by creating a new centre of interest that would attract business away from Cannaregio. This could be done by revitalising the area, converting and renovating the run-down real estate and encouraging more productive activity there. The jobs, the new interest, and the easier access the new bridge would create were all facts that they hoped would help to halt the progressive displacement of the city’s axis. The alternative, undoubtedly more complex, suggested a much wider view of the city’s economy and urban planning. This would not entail the revitalisation of Dorsoduro (which would be seen as more of an accessory), but rather of the old centre of the city and its port services. (Around 1835 there was a project proposed by Gaspare Biondetti Crovato to extend the railroad along the Zattere ending at the island of S. Giorgio and to create a commercial maritime station near it. The value of the emporiums of Dorsoduro, far from being diminished, would go sky-high).

Thus, the S. Marco basin would return to be the centre of economic and cultural activity by strengthening and updating the old equilibrium.

The Bridge of the Carità would have the delicate task of being the pedestrian link between the historic civic centre and the newer, now closer, commercial zone of the railroad and maritime station.

The unquestionable confirmation that there was a basis for this concern came five years later when the Camera di Commercio gave Giuseppe Jappelli the task of elaborating a plan for an ‘entrepot’ along the bank of the Zattere; Jappelli’s proposal foresaw the necessity of a bridge linking the point of the Salute with the District of S. Marco at S. Moisé. However, in the minds of the promoters of the Carità Bridge it is unlikely that these plans appeared this simple and schematic bearing in mind the immediate implications on property in the area. In fact, it seems clear that the bridge was only one aspect (however central) of a larger and more broadly based plan which would affect the future of the entire city.

On November 24, 1813, the City Council met and decided to announce a competition in collaboration with the Academy of Fine Arts and a group of ‘reputable engineers’ with a prize (100 recchini) for the design of the proposed bridge. It is important to note the recognition given to the engineers, for the architects and the Academy were relegated to the task of ornamenting the bridge. At this point a further complication arose when a council member, Alvise Francesco Mocenigo, brought up the suggestion that, given ‘the advances of modern science today, why not build a tunnel under the water?’. Despite the Mayor’s protests, Mocenigo defended his point of view and succeeded in having the competition called for a ‘means of communication’ and not necessarily a bridge. He obliged the Committee to reassess the competition programme in the areas of the toe of communication and its location. Because of his authority, technical competence, and fame, Paleocapa was immediately held in high regard in Committee discussions and he often had the final word on the problems. According to the records of the meeting, Paleocapa presented his opinions, supported by a series of data and technical considerations so detailed that the members of the Commission could neither contest nor verify them, in such as learned and calm manner that he guided the discussions to their final decision.

Almost every imaginable type of solution for a mean of access, by bridge and tunnel, was presented to the Commissioners; in the case of the bridge, should it be fixed or one which opened (and this should be a drawbridge or a sliding bridge; made of iron or stone, with one or more arches? and every possible location between S. Maria de!

Giglio and the S. Gregorio ferry landing, and between the campo of S. Vidal and the Carità was suggested.

In regards to the alternative between the ‘fixed or openable bridge’, the majority of the commissioners voted for the latter solution so as not to bar the central part of the Grands Canal from the traffic of the larger boats. However, the decision proved too hasty and it was promptly overturned in the second meeting.

At this point Salvadori objected to the enormous expense in manpower it would cost the Municipio to operate a bridge which could be opened (sliding, draw, or turning types). Meanwhile, it seems that Paleocapa was quite clear, for political reasons, on the choice to be made, and today (because we are still dealing with these same problems) his words have a familiar ring: ‘Moreover, it seems wise to consider that the palaces (which are some of the most superb in the city) located in the part of the Grand Canal from S. Vitale to the Rialto and which are now used as warehouses, could be put to some other use. Ca’ Foscari already has a function that does much more justice to its beauty, and I believe that will also happen to Ca’ Giustinian and the other palaces of Dorsoduro, where the new communication artery allows the district to acquire greater importance…’, in short, so that the negotium does not disturb the optium (especially when this could confer more than ‘arbitrary value’ on its/his/structures).

Immediately discarding the idea of the underwater tunnel (because of the expense, the technical difficulties, and the lack of certainty about public response) the Committee reached a provisional settlement in an unofficial statement: ‘We have rejected the idea of the tunnel because the funds budgeted for this access would not be sufficient to bring the project up to the full potential we foresee for it, nor does it seem a comfortable solution for the public, and we would also be left without a majestic, new work to admire. The Commission has agreed that the best solution to link the two banks of the quarters is a bridge which can be opened, and the question has been raised as to whether, following the lead of other great European cities, Venice could construct a drawbridge without disturbing the layout and beauty of the city’. However, Paleocapa then pointed out that a bridge of this type would have to be manufactured with arches, with its pilings planted in the middle of the Grand Canal for support purposes, or else it would have to be constructed in wood. At this point Lazzari brought forth his idea, which he had been promoting since the very beginning to construct an openable timber bridge after the model of the old Rialto Bridge as seen in illustrations by De Barbari or Carpaccio. Paleocapa, however, succeeded in influencing the final decision in favor of his hypothesis: connecting the Carità with S. Vitale with a fixed, metal bridge. It is worth noting that Paleocapa thereby aided and consolidated the future fortune of these two great traffic ways: from S. Vitale to S. Marco (by S. Maria del Giglio – S. Moisé).

The Commission’s work ended with four resolutions that were presented to the Communal Council:

- The two quarters must be connected only by a fixed bridge;

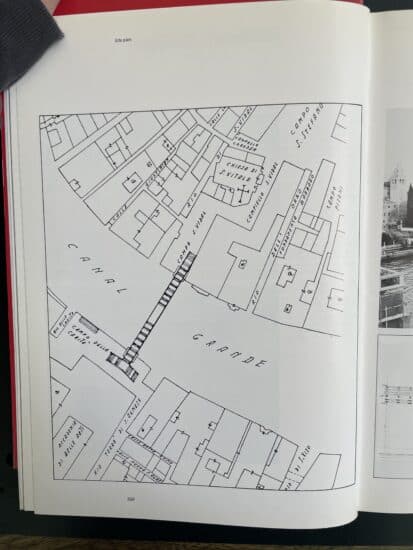

- The line of connection should be between S. Vitale and the Carita, and Rio S. Agnese must be filled in;

- The bridge will be a suspension bridge, seven meters wide to correspond with the width of Rio S. Agnese, and the Grand Canal should be left free of pilings; the required space on both sides of the Canal must be acquired from the owners;

- Paleocapa and Salvadori will present to the Municipio ‘a general outline for the estimated costs of the construction, the materials, and the land needed for access on both sides of the Canal; the Count Mayor will be responsible for awarding the contracts to the various companies’.

Mayor Correr and Councillor Dona reported to the Communal Council on March 28th: the Commission’s proposals had all been accepted, as well as the ceiling cost of 330,000 Austrian lire: they also agreed to allow the contractors to choose the means of payment by installment over a six-year period or by collecting the tolls generated by the bridge).

In the meantime, various groups agitated for other solutions: to build the bridge between S. Gregorio e S. Maria del Giglio instead, to go back to the idea of a bridge which could be opened, or not to build one at all, but all protests were to no avail. The proposal continued on its way, and was passed on through the Regia Delegazione, the Congregazione Provinciale, the Eccelso Governo, the Coneregazione Centrale, the Direzione Centrale delle Pubbliche Costruzioni, the Supremo Comando della Marina and the Comando della Città and Fortezza. But subsequent steps were not easy ones: in a notation dated September 9, 1845, the government asked the Commission to reconsider the problem and its various alternatives between the bridge and the tunnel, and the moveable or fixed proposals.

At this point Salvador presented his extremely interesting studies for a tunnel and bridge with a marble pilings, and different versions dating from 1843 and

’45 were also presented (the earliest being the 1838 study for the visit of Ferdinand I). All were re-examined and rejected again just to humour the government and to make the Consiglio Comunale secure in its choice. The tunnel and the marble bridges were studied for the S. Vitale-Carità line and for the S. Maria Zobenigo-S. Gregorio one. These plans were extremely detailed and well done, but they exorbitantly inflated the costs (even Paleocapa noticed it in order to demonstrate that they were inconvenient and impossible to build). In the end the only solution left was the fixed suspension bridge. While the plan passed from one office to another. Correr gave Salvadori the go ahead for the executive stage in March 1848 (starting with evaluations of the buildings which would necessarily have to be demolished). Unfortunately, the political upheavals in Europe at the time succeeded in bringing the project, when it was just getting off the ground, to a complete standstill.

The idea for the construction of a bridge was shelved for quite a long time.

At the beginning of 1852, the great entrepreneur and engineer, A.E. Neville, reproposed it. He produced studies of 37 suspended iron bridges from the whole of Europe (Belgium, Austria, England) and a new construction technique of his own invention. With the unquestionable excellence of his firm’s credentials along side with the great savings he predicted for the project, Neville seemed destined to win over all forms of resistance from the beginning.

Salvadori, who was by now an expert in Venetian bureaucracy, especially when building was involved, immediately gave up, with considerable regret, the hypothesis he had worked on and perfected over a thirty-years period. The judgement he gave on the technical part of Neville’s project was decisively positive, and he concluded: ‘Regarding the aesthetics of the bridge, most people will probably dislike its narrowness, the tall poles of iron top, or the wood frame support decorated with iron crowns, whose lines will interrupt the salient form of the bridge; yet, the idea will prevail because of the economic savings, the opportunity for jobs, and Venice’s satisfaction in being the first city in Italy to possess a bridge constructed with a totally new type of system’.

The major novelty in Neville’s bridge design was that is was neither an arched type, nor suspended by chains, but a straight span of 50 metres. The bridge as initially predicted did not please the Commission appointed to study the project (the new Secretary of the Academy, Marquis Selvatico, Engineer Tommaso Meduna, Architect Pigazzi and Historian Zanotto). They proposed a modification in the ornamentation, and, showing little understanding for the technical aspects of Neville’s design which underlay its section, again asked for an arched iron bridge, for which they prepared a sketch which disappointed the planners. They finally handed Neville’s proposal over to the Ornamentations Committee who approved it.

While Neville was trying to raise support for his project, the Dorsoduro property owners signed a petition in favour of it that was too much of a coincidence to be a mere chance. Appearing on the list were powerful and illustrious names:

Filippo Nani Mocenigo, G.B. Giustinian-Recanati, G.B. Giustinian, Countess Esterhazy, and many others. On May 10, 1852, the Comunal Council approved everything: the execution, the building techniques, the budget, and the time schedule.

The next phases were mainly those of the works’ progress: the construction by the Municipality of the two bases for the anchoring of the bridge; the defining of its exact axis; the arguments with Neville because he did not want to be subordinate to the Ornamentation Committee over the choice of decoration, and other minor obstacles. After the bridge was tested with brilliant results on the 14th and 15th of November, 1854, it was opened to the public at 2:00 P.M. on the 22nd of November. In honour of the event the tolls collected that day were donated to charity. The citizens not only found themselves with newly renovated streets, but also with a wonderful, new, metal bridge of which they could be very proud (Venice ‘was the first to possess a bridge constructed by this new system’ in Italy). This manufactured structure was also quite typical of those years, the ornamentation and over-all appearance being unequivocally British in flavour, and, by association, typically British in its commercial, industrial and traffic implications.

In the course of the next fifteen years the urbanistic significance of the bridge slowly changed. It is also true that already in 1853 the owners of the loading docks between S. Vitale and Rialto asked again for an openable bridge. It almost seemed as if they were longing for the position they had ten years before. The city was then going through a moment of economic decline and misery; but now that it was on the road to recovery, the problem of the port facilities and traffic took on another aspect. It seems that the Grand Canal was too narrow to handle the large shipping traffic, so the Giudecca Canal (even though Jappelli’s project for the National Entrepôt was never realised) became the centre of commerce. At this time, in fact, the disputes over the location of the Commercial Warehouses began. This change, however, did not diminish the importance and significance of the Accademia Bridge: but it rendered it simply an updated means of internal communication (in a modern way, by metal bridge rather than a ferry system) depriving it of its productive role. It could hardly have been otherwise unless it had been seen … as indeed at the outset it was … as part of a larger issue of urban development in Venice instead of simply as an issue of communicational viability in the city centre.

That which has recently been defined as a ‘horrible, long cage’ and an ‘ungraceful, cast iron structure’, appeared to be a manufactured article with sound formal qualities and quiet, unpretentious dignity. This product of European industrial design had two great assets: its structure allowed it to be simply placed on the two prepared bases without having to do any excasting, demolition, or major construction for foundations, and its transparent appearance—its neutrality—(which can be seen in eloquent photographs) did not hinder in the least the urban view that replaced it in 1932.

(From G.D. Romanelli, Venezia Ottocento, Rome 1977, pp. 215-26)

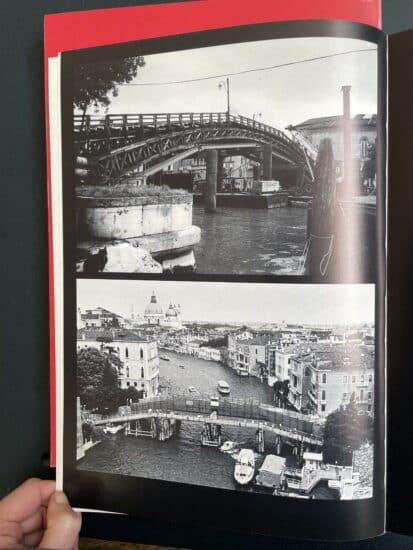

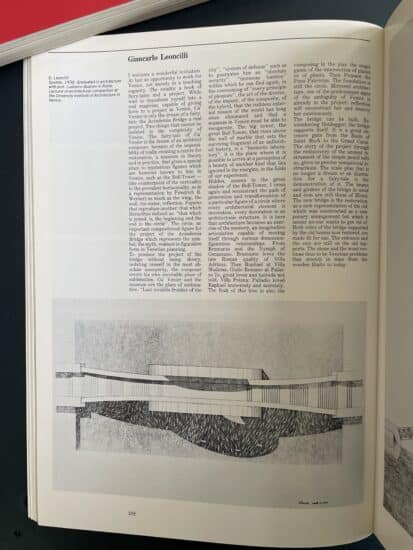

This documentation needs to be integrated with the construction of the temporary bridge built in 1932 and still in use today.

Neville designed a modern, reticulated, iron structure, resting on anchorages which are not quite in the same positions as those of the present bridge and which seemed substantially provisional. This linear bridge had, therefore, an appearance similar to that of other important construction carried out during the Austrian occupation, that is to say the Scalzi Bridge, completed only four years after the Carità bridge. In this way Venice’s traffic network underwent a radical transformation. In fact two important new bridges were added to the traditional connecting and penetrating link represented by the Rialto bridge. The hierarchical balance in the traffic network, which had been maintained for centuries, was thus shaken, and so much so as to make it seem possible to state that such constructions were the most telling. feature in the XIX-century modernisation project of Venice’s urban lay-out. Moreover Venice was a city capable of opposing this destiny with widespread resistance which in many ways was destined to have success.

Although its supports on either side of the Grand Canal were architecturally in line with the tastes of the time, Neville’s bridge still seemed like a substantially temporary structure. It was really a footbridge which, once having outlived his purpose either statically or as part of the traffic network, could be easily removed. When this need could no longer be put off the immediate decision was to provide for the building of a new temporary bridge. It is useful to note how, on that occasion, the utility of the bridge was not questioned. It was thought that the bridge still fulfilled an essential role, in spite of the fact that the hopes which were cherished when Neville’s footbridge was built, had hardly been satisfied during the intervening eight years.

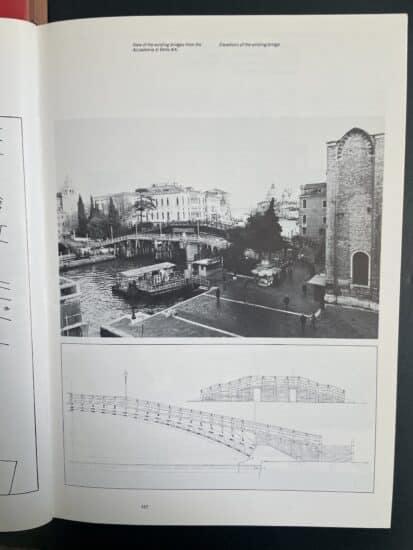

However, the decision was to proceed without delay with the construction of a temporary wooden bridge, while awaiting the results of a competition which was to produce sound suggestions for the permanent bridge.

While the construction of the temporary bridge was being completed, the competition failed to provide any suggestions which were considered valid.

On the other hand, the temporary bridge was designed to last far longer than foreseen in the circumstances which encouraged its rapid construction.

Indeed, the bridge designed in 1932 is basically the one which is still used today. Of course some changes have been made to the original structure over the years, mainly to guarantee its stability. Ironically, this temporary structure has needed to be restored many times. One of the most important restoration was carried out in 1948 by the Breda Company, specialised in metal constructions, and this emphasised the ambiguous nature of the bridge which is now a curious mixture of structures.

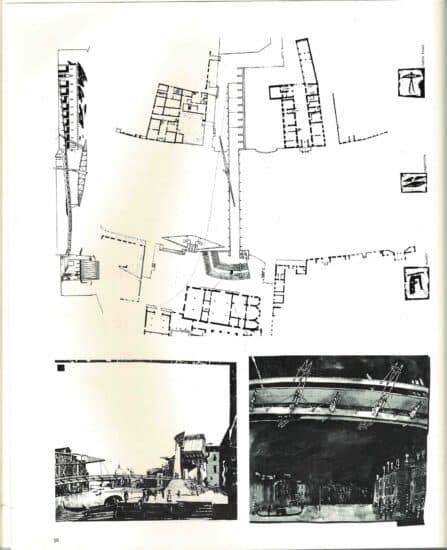

The present-day bridge unites the two banks of the Grand Canal linking Campo San Vidal to Campo della Carità. Its ground anchorages are not in the places used for those of Neville’s footbridge. This has caused several formal problems and incongruities, acceptable in a temporary structure but intolerable in a structure of such importance which furthermore was destined to outlive its original lifeplan by more than fifty years. The precariousness of the position of the temporary bridge—it must be stressed that the precariousness derives from the movement of the anchorages by a few metres—is made clear by the two forms taken by the approach ramps. One of these in particular, the one facing the wall of the Church of the Carità, appears to be especially problematic.

The deterioration of the supporting structure after 1948 has required continual restoration work. However, in spite of this, it has recently been necessary to restrict the area of the bridge actually walked on, preventing its use on special occasions and limiting direct contact between the passers-by and the original wooden balustrades by putting up barriers which are also temporary.

While the bridge, by now unsafe, is today heavily restored by resorting to an independent and imposing supporting structure—also temporary but destined to last for another fifty years?—the problem remains of finding a permanent solution. All the proposals, which this initiative of the Biennale aims to produce, can contribute to this solution.

Dear Peter,

I hope you are both well.

We were just inching forward with our Pont des Artes and the Accademia Bridge postings.

And then, we noticed that the three Accademia Bridge proposals we have represented here—your own, Dario Passi and Luc Deleu—were not included in the ‘official’ listings and publications. Was there an... Continue Reading

Dear Peter,

I hope you are both well.

We were just inching forward with our Pont des Artes and the Accademia Bridge postings.

And then, we noticed that the three Accademia Bridge proposals we have represented here—your own, Dario Passi and Luc Deleu—were not included in the ‘official’ listings and publications. Was there an alternative entry, or is there some juicy background we don’t know? It would be fun to know more.

Niall

Dear Niall,

How nice to hear. Your mail followed me to Thurloe Square, where I am looking at the little Pont des Arts model on the top shelf. Also the somewhat larger Accademia model is mounted on a wall here—both yours for picking up.

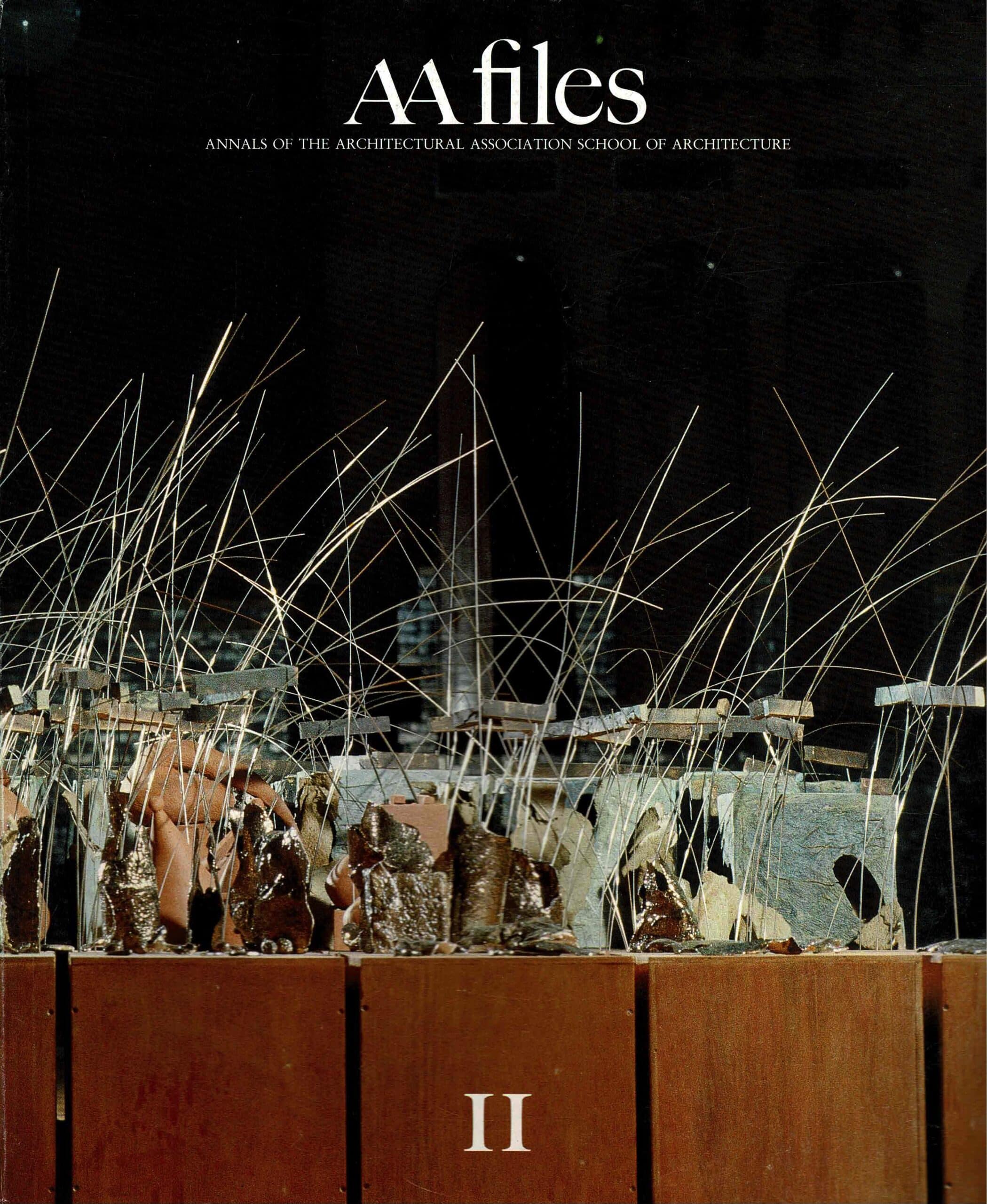

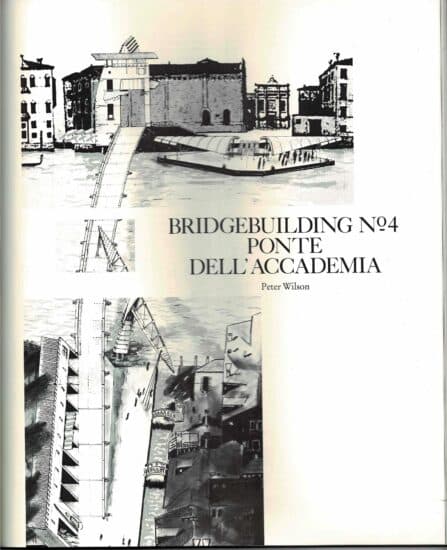

Regarding the Ponte della Accademia, you will not find it on any official lists as Rossi did not select my somewhat gothic entry for the exhibition. Peeved, we took a Salon de Refuse trajectory and published it in AA Files magazine, made the model and exhibited it at the AA.

Warmest,

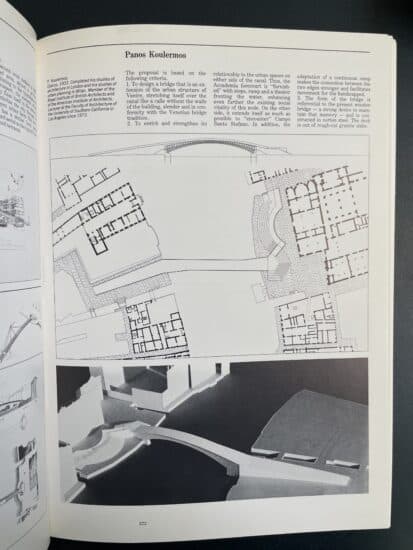

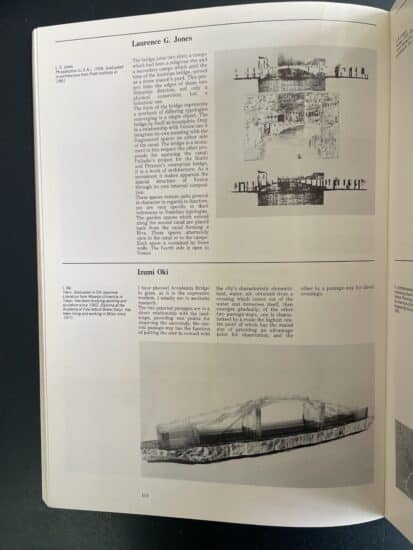

Peter