Anna Atkins: Laying Out the Blueprints

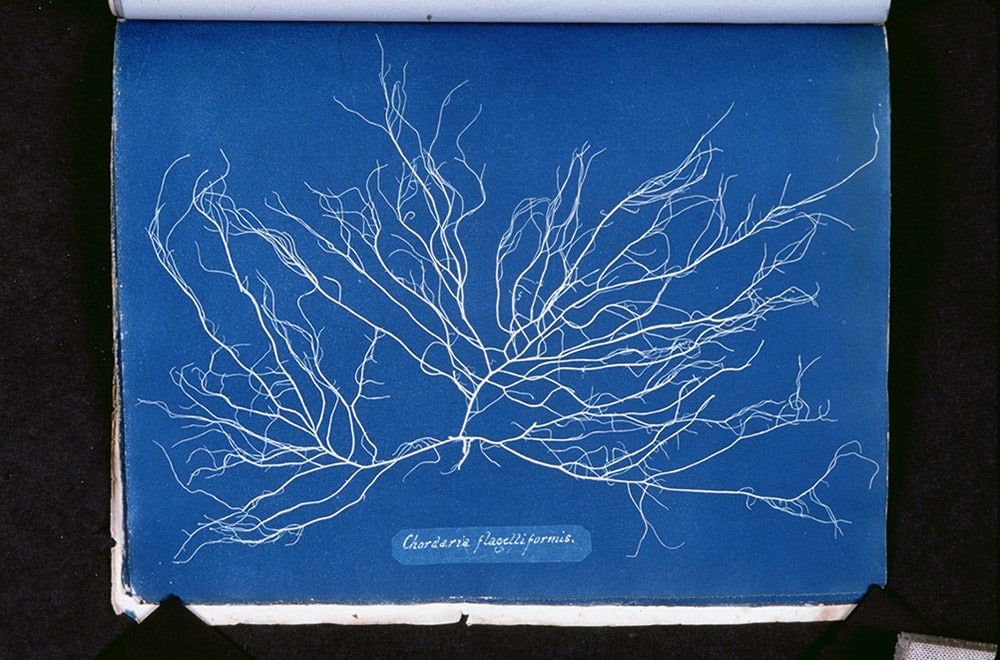

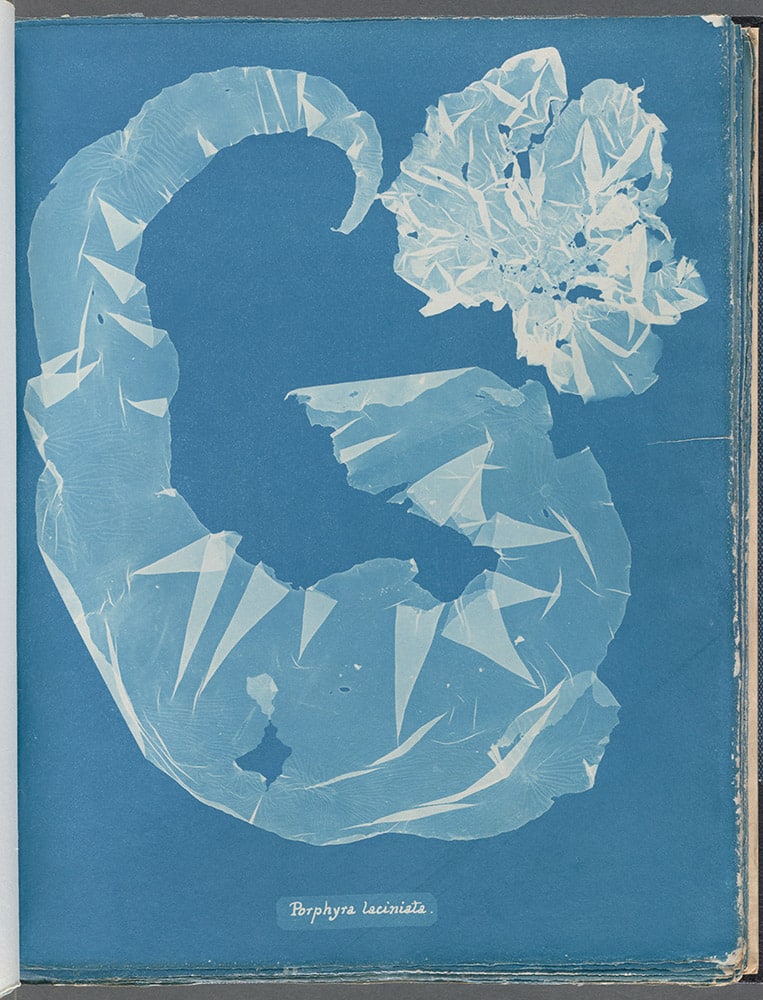

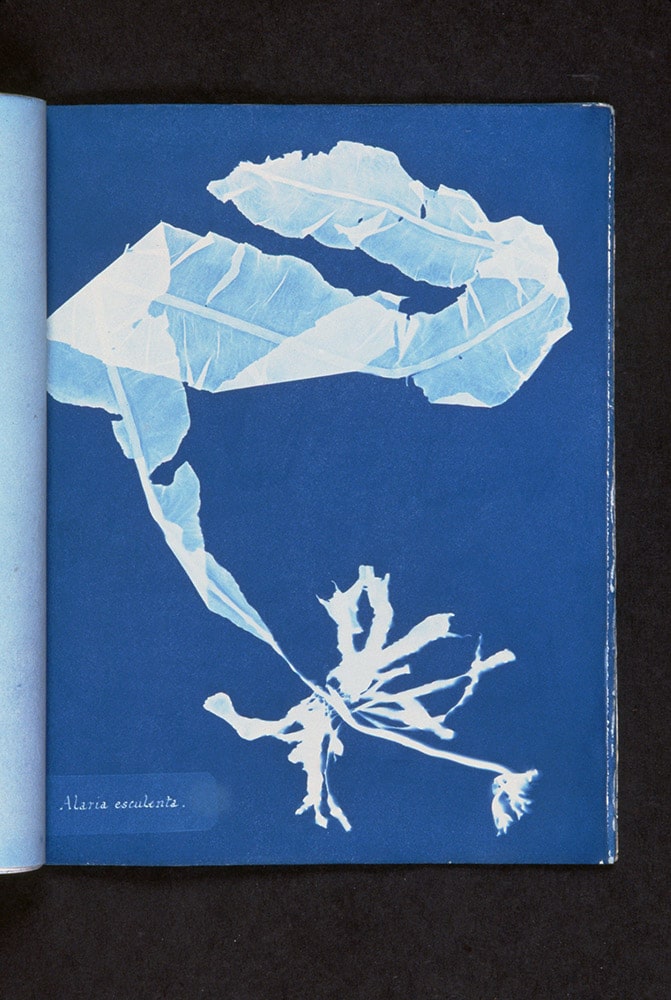

They began to bloom on websites a couple of years or so ago – stretching out on social media, unfurling in the arts sections. Pale alien shapes suspended in deep blue: something like lightning flattened in a flower press; a sleeping creature emerging from a cloud of coral; a spectral plume, somewhere between feather and smoke. I was drawn to these images, presuming they were paintings, not quite sure. They were photographs. Cyanotypes to be precise: objects placed on chemically treated paper and exposed to sunlight. Some of the very first ‘blueprints’ – the same method once used by engineers and architects to rapidly reproduce drawings.

The images are of algae, made by Anna Atkins in the mid-1800s – the first woman to take a photograph, forgotten for over a century. Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, from which the images are taken, is now recognised as the first ever photobook, literally laying out the blueprints for a format essential to the medium.

Atkins’ work was rediscovered in the late 1970s, but an influx of interest occurred just a few years ago. This might be down to climate more than coincidence. It took a particular time to immortalise Atkins – not just one when issues of gender and representation are at the forefront, and environmental awareness at an all-time high, but one obsessed with both aesthetics and the analogue. In an era when culture is dominated by the image, and younger generations are shifting from the convenience of digital to slower forms of expression, Atkins’ remarkable creations have moved from the specialist to the mainstream, transcending from function to art. Atkins has found her moment – one when teenagers shoot film, and Victorian botanical drawings are torn from antiquarian books and framed in cocktail bars. After being ignored for generations, it took the specific values and tastes of millennial culture to appreciate the impression Atkins left, gently shake away the dust, and restore it to its rightful place on our collective shelf.

Nicholas Herrmann is a writer, editor and film photographer.

This text was submitted in the short form category (≤ 350 words) of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2020.