Aux Citoyens Membres de La Commune attachés à la commissions des services publics

i

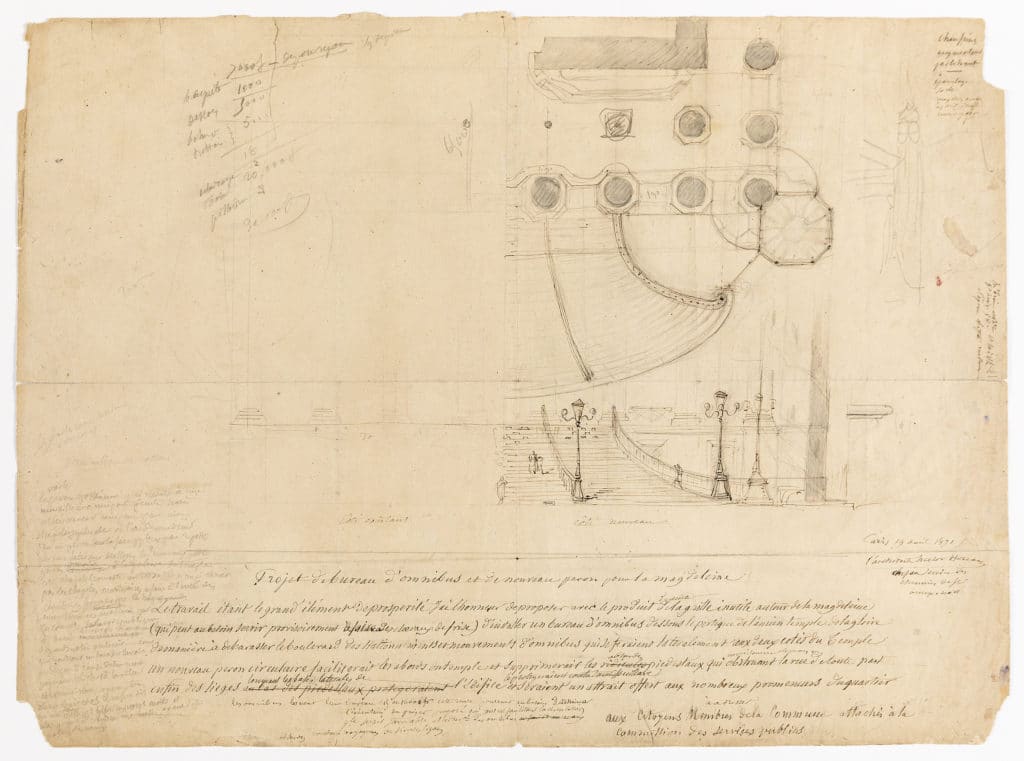

Hector Horeau’s sketch of the Church of La Madeleine came at the height of the Paris Commune – the radical socialist regime that governed the French capital from 18 March – 28 May 1871. Although dated 19 April 1871, the drawing is on the verso of a frontispiece to Panorama D’Égypte et de Nubie, an anthology of vignettes that Horeau produced based on his travels around Egypt in the late 1830s. At some point in time – perhaps between the printing of the anthology in the 1840s and Horeau’s reuse of the page thirty years later — the page has been folded, segmenting its surface into four parts. On either side of the central crease are two views of the Madeleine’s southern portico. On the left side, precisely articulated in faint pencil, is the neo-classical façade of the Madeleine. On the right side, continuing the pencil drawing, is Horeau’s revision of the staircases that lead up to the portico. Above it is the same view in plan.

The two parts of the drawing divided by the crease are a ‘before and after’ of the church. Horeau’s rendering of the façade on the left becomes a palimpsest on the right, overwritten by his proposed revisions. In the elevation and plan on the right side, Horeau describes a rounding of the southern staircase and the removal of protruding pedestals from the podium to allow lateral access and sight from the eastern and western approaches. Subtly inserted into the elevation — but expressed more clearly in plan — is one of the four turrets that Horeau proposed to install at each corner of the existing building.

From the drawing alone, Horeau’s proposal may seem like a mere facelift to an extant building. However, the inscription below, written in Horeau’s hand, reveals that the architectural changes are linked to a change in programme and typology. As the architect describes, the drawing depicts a project for transforming the Church of La Madeleine into an omnibus bureau, with lateral carriageways for the circulation of vehicles.

ii

Horeau’s proposal may seem like a radical change, but it was merely one episode in the site’s spotted history. Designed by Pierre-Alexandre Vignon as the ‘Temple to the Glory of the Army’ under Napoleon in 1806, it was not until the reign of Louis XVIII that the Madeleine was determined to be a church. Originally proposed as a replacement for a smaller church, successive periods of political change and hapless architectural competitions complicated its construction. During this time, the building’s programme was even debated; as late as 1837, there were suggestions that the Madeleine should be used as a railway station. Finally, though, in 1842, the Madeleine was consecrated as a church.

On 3 April 1871 the Paris Commune declared the separation of the Church and state, reviving the debate around the use of the Madeleine. [1] In the eyes of the Commune, the Church was complicit in the tyranny of the monarchy, and, as a result, a policy of secularisation was enacted throughout Paris. The peak of this was the execution of a number of high-ranking members of the clergy. On 24 May, the fourth day of the so-called ‘Bloody Week’, Abbé Deguerrty, the curé of the Madeleine, was executed alongside the Archbishop of Paris. These executions were an act of retaliation against the execution of Communards by government troops, who were closing in on the city. In the ensuing days, the government’s grip on Paris tightened and by 28 May, the Communards succumbed to the government’s advances.

iii

Had the Commune’s seizure of power not been over so soon, the fate of the Madeleine itself may have mirrored that of Abbé Deguerrty and the Archbishop. Hector Horeau, as the Commune’s ‘head of hygienic building’, saw the Madeleine as problematic, and in a commentary accompanying an 1869 drawing of the church, the architect outlined a twelve-step manifesto for remedying its grave inconvénients. [2] These included criticisms of its poor pedestrian and vehicular circulation and the removal of metal grills to prevent the buildup of refuse.

Interestingly, however, given the Commune’s opposition to the Church, Horeau did not include the Madeleine’s ecclesiastical function as one of its issues. In fact, what he did take issue with was its un-Christian character, or more accurately its imbalance between being a temple dedicated to Napoleon’s military glory and fitting the codified idea of what a church should be. To remedy this issue, as shown in the 1872 drawing, Horeau proposed the addition of four turrets to the building. Dedicated to the evangelists and featuring electric clocks and bells, these four turrets were Horeau’s method for adding to the Madeleine the Christian trappings that it lacked.

Horeau’s interest in making the building more conventionally Christian may seem contradictory, but it represents a desire to disassociate the building with Napoleon. The destruction of the Vendôme Column during the Commune, which had been described by the artist Gustave Courbet as a ‘symbol of brute force and false glory’, reflected similar antipathy towards Napoleon and his imperial rule of France. However, in contrast to the demolition of the column, as shown in the 1871 drawing, Horeau’s alterations were not solely iconoclastic: he desired to transform a symbol of Napoleonic imperialism into a civic building that prioritised cleanliness and rationalisation, and would serve the citizens of Paris.

Important to this was Horeau’s proposal for transforming the Madeleine’s relationship with the urban composition of its surroundings. Not shown in the 1871 drawing, but explained in the 1869 iteration, are a number of measures which would have made the Madeleine-as-omnibus-bureau into the centrepiece of an urban design. These measures included a fixed iron gallery on the north approach to separate pedestrians and cars; cellars to hide away services and the unsold flowers from the flower market; the installation of fountains; replacing metal fencing in the bays between the columns with seating; and establishing wide, tree-lined carriageways around the building and, on Rue Tronchet, portable boxed shrubs surrounded by seats.

iv

The April 1871 drawing is an iteration of the scheme executed at a crucial moment. The inscription below the drawing, in addition to explaining what it depicts, also serves as a dedication. At the bottom of the page, Horeau writes: ‘to address the citizen members of the Commune attached to the commission of public services.’ The drawing, then, appears to be Horeau formalising his pitch to the other members of the Commune, a finalisation of a radical project at a time of great febrility. Of course, unfortunately for Horeau, his proposal was inopportunely timed — only a matter of weeks before the fall of the Commune — and it is not clear whether he ever had the opportunity to present his scheme to the other members.

As for Horeau himself, after the Commune’s fall he was imprisoned on charges of impersonation and held at Versailles before being transferred to a pontoon on the River Orne and then to the Island of Aix. Still, though incarcerated, Horeau continued drawing-up schemes for architectural transformations. While on the pontoon, he devised a scheme to replace the Hôtel de Ville de Paris, which had been razed as a last stand by the Communards. Horeau’s imprisonment lasted for five months and profoundly affected his mental and physical health. He died on 21 August 1872. [3]

[1] See https://www.marxists.org/history/france/paris-commune/documents/church-state.htm for the full ‘Decree on the Separation of Church and State’.

[2] For a reproduction of the drawing and transcription of Horeau’s commentary, see Françoise Boudon and François Loyer, Hector Horeau: 1801–1872 (Paris: Centre d’Etudes et de Research Architecturales [C.E.R.A], 1972), p. 126.

[3] For a more complete biography of Hector Horeau, see Paul Dufournet, ‘Les Etapes de L’Existence’, in Boudon and Loyer, Hector Horeau: 1801–1872, p. 143.