Behind the Lines 12

1870

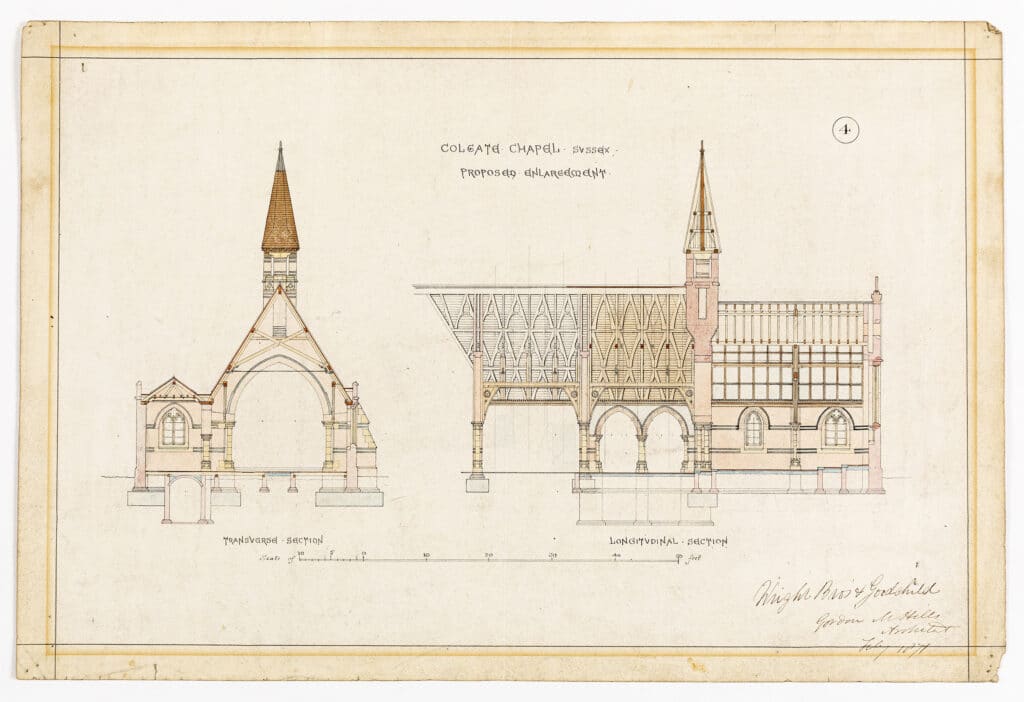

Colonel James Clifton-Brown, newly established at Holmbush, his Regency country house in Colgate, West Sussex, has political ambitions – namely, the parliamentary seat for Horsham. He observes that the villagers have only a small cramped chapel in which to fulfil their ambitions to be good Christians. The chapel is not an ornament to the neighbourhood. Being the principal landowner, he wants to worship in a decent church with its own vicar, not a roadside chapel erected by his predecessor at Holmbush, Thomas Broadwood. By instigating and funding these improvements James Clifton-Brown reckons he will be laying down treasure in heaven – while simultaneously gaining credit with the local good and great. He calls on his Lower Beeding neighbour, William Hubbard at Leonardslee, on the pretext of admiring his wellingtonias, and succeeds in getting a helpful contribution to the expense of enlarging the chapel and building a vicarage for the incumbent. The estimated total cost is £2,700.

In the course of his discussions with the Bishop of Chichester about the creation of the benefice of St Saviour’s (as the church was to be dedicated) the Bishop recommends Gordon Hills as architect: ‘sound fellow and a devoted servant of the church’. On this matter the Bishop has first-hand knowledge, since fixed painfully in his memory is the sight of Hills locking the door of Chichester cathedral just minutes before the spire came crashing down on 21 February 1861. Hills and a team of builders had struggled for several days to shore up the crumbling masonry and failing piers. They failed. Hills had been the last man to leave and had written in The Builder a few months later: ‘Chichester has received a heavy blow, and England a warning.’

1871

Gordon M Hills, a middle-aged architect, sits in his office in St John Street near the Adelphi; he has just been appointed Diocesan Surveyor to the dioceses of London and Rochester and feels extremely overburdened with work. His ambition is somehow to find the time to write up his proposed paper on acoustic vases for the British Archaeological Society.

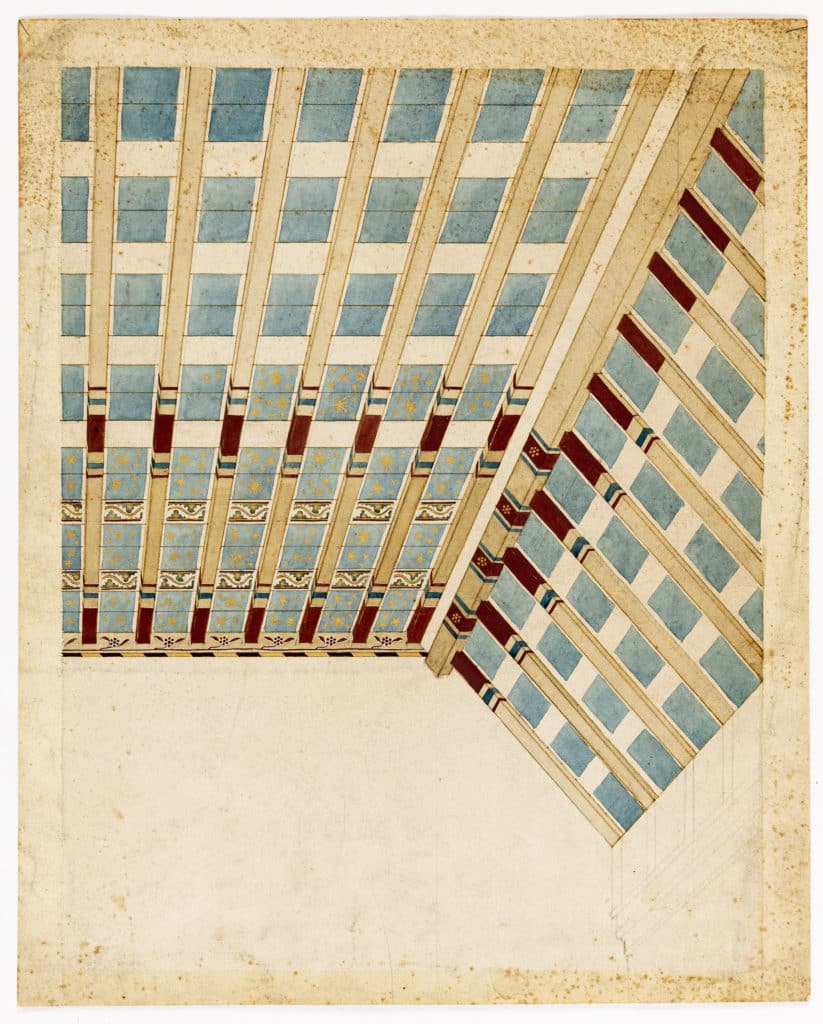

He ruminates on his new commission in Sussex and works on the drawings. Last year he had visited Oxford and been vastly impressed by the polychrome brickwork of Keble College; he resolves that at Colgate he too will build in red, white and grey brick with stone dressings. He envisages Minton tiles on the floor, and richly coloured stained-glass windows. The roof of the chancel he wants to be decorated with gold stars on a sky-blue ground. Recently while studying monastic ruins in Devon he had seen the roof of St Nectan in Hartland with exactly such a device and thought it exceptionally fine.

1871, maybe 1872

The builders, Messrs Wright Bros & Goodchild, are making good progress with the foundations. Hills realises he must get ahead with commissioning the stained glass for St Saviour’s. James Clifton-Brown’s mother, Sarah, an alarmingly decisive woman with a tendency to interfere, has selected the text that the west window must illustrate: ‘I am come that they might have life.’

Leaving his office, Hills crosses the Strand and walks up to 44 Garrick Street to the workshop of Heaton, Butler & Bayne, designers and manufacturers of stained glass and ecclesiastical decoration. He is carrying two drawings, one a transverse and longitudinal section that shows the window openings for the stained-glass artist, and the other his ceiling plan. Hills shows it to Robert Bayne, he is hoping that as the firm undertake murals as well as stained glass and mosaics they will have a painter to carry out his design. He leaves the drawings behind for Bayne to consider and starts worrying about the restoration of Pulborough church, on which matter he is being hard pressed.

1940

Shortly after the outset of war Basil Bayne, grandson of co-founder Robert Bayne, gives up the Garrick Street studio and moves all the drawings and records to the Glass House in Fulham, a stained-glass studio built in 1906 by Alfred Drury and Mary Lowndes.

March 1953

Basil Bayne dies; Heaton, Butler & Bayne for 90 years one of the foremost stained-glass companies in England, closes. Basil’s widow, Simone, is thwarted in her ambition for the firm’s archive of cartoons and drawings to go to a national institution – none are interested. She hires a lorry to move everything from Fulham to her home, Glen-Arden, Marsham Lane, Gerrard’s Cross. She has bonfires of the large cartoons, as she puts it in her memoir of the company, ‘on account of the difficulty that their bulk posed’. She stores the smaller drawings.

Spring 1975

Basil and Simone Bayne’s only son Malcolm is killed, aged 20. Simone decides she will leave her painful memories in Buckinghamshire and return to her native Switzerland. During the packing up of the family house she consigns the remainder of the Heaton, Butler & Bayne drawings to Christie, Manson & Woods, auctioneers of St James’s Street, SW1.

22 July 1975

The Property of Mrs SBM Bayne, Lots 226 – 225, comprising approximately 3,548 designs for stained glass windows, walls, screens, ceilings and mosaics are sold. ‘The present designs are all unframed and are for the most part in watercolour. The majority are numbered, and for convenience and to preserve a chronology, the lots have been arranged in numerical sequence. These numbers presumably would have referred to an inventory, but unfortunately this is lost. As a result, few of the drawings can be definitely connected with named projects.’

Autumn 1975

Thomas O’Neil of 8 Elsinge Road, Wandsworth, buys, on a whim, a couple of drawings. He doesn’t admit it to anyone, but the pale blue and gold stars of the ceiling design remind him forcibly – and happily – of the wallpaper in his childhood nursery. The dealer has written the provenance on the back of the drawing: ‘From the workshop of Heaton, Butler and Baynes’. He is cultivating an interest in Victoriana that goes some way to offsets the boredom of his job in the wine trade. He has just met a girl called Janet Wells; his ambition is to persuade her to live with him.

Thursday 16 September 1976

Thomas O’Neil writes the following note and sellotapes it to the back of a picture.

‘For Andrew,

Thank you so very much for bringing my picture back – I thought this was a better idea than a new pair of jeans as it is something I think quite beautiful

Love T.’

He has promised his old friend Andrew Hardcastle a present in return for driving over to Ireland to pick up a painting left to him by an elderly O’Neil aunt. Andrew, whose ambition is to cut a dash as an actor, had suggested that a pair of Levi 501s – emphatically not Wranglers – would be a good reward. Thomas, short of money, is very reluctant to spend what he believes to be a ridiculous amount for a pair jeans, even ones with brass rivets. Instead, he chooses, reluctantly, to give Andrew a couple of drawings that that no longer fit into his life. Janet is keen on Art Deco and filling the house up with Erté graphics and Clarice Cliff ceramics. Besides, Thomas thinks it very unlikely that Andrew will make it as an actor, despite his recent breaks: a small part in Z Cars and a stint at Farnham rep. The drawings will give him far more enjoyment than jeans when he returns to Yorkshire to join the family wool business, and his jeans moment will pass, maybe sooner than he thinks. He will invite Andrew to be his best man when he marries Janet next Autumn. That evening Andrew staggers through the door of 8 Elsynge Road in Battersea with a very large Victorian oil painting titled Cattle at Sunset. Thomas is disappointed; Andrew too.

30 November, 2017

Morphet’s Fine Art Auctioneers and Valuers, Harrogate.

Lot 526 English School (nineteenth century) architectural drawings of Colgate Chapel proposed by Gordon M Hills architect, Wright Bros & Goodchild, Feb 1871.

Watercolour over pencil, inscribed, 31 cm x 46.5 cm together with architectural detail of rafters painted in the Arts and Crafts style, watercolour over pencil, unsigned 36 cm x 28 cm.

The two drawings are knocked down to Niall Hobhouse in Yarlington, Somerset. ‘That was an interesting way to represent a ceiling,’ he thinks.

Notes

Obituaries of Gordon Hills

The Builder vol 68, 20 April 1895, p 302.

RIBA Journal vol 2, 1895 p 452–53. This provided the information about Hills’ connection to Chichester Cathedral, which is I assume how he got the commission to rebuild Colgate.

The Electoral Register (thanks to library at London Metropolitan Archive) provided me with the surnames of Tom (O’Neill) & Janet (Wells) at Elsynge Road. They did indeed marry in 1977. Wine trade? Who knows? Of Andrew and how the drawings ended up in Harrogate, I had no clues, so the character of Andrew Hardcastle is entirely invented

A photograph taken by WD Caröe in 1909 (Historic England archive AL0407/356/05) shows the stained glass windows but no sign of a painted ceiling. Caroë had been commissioned to make improvements to the chancel in memory of Sarah Clifton Brown.

John Sired, present Churchwarden of St Saviour’s: ‘Sept 9th 1940 for some reason a German aircraft dropped a number of bombs on the village my wife’s uncle Jack Constable and 16-year-old William Doik who had already lost his father in action, both went to help. A second stick of bombs made a direct hit on the village nurses house killing five people including the nurse and the two people mentioned. The following morning my wife’s mother R Constable ventured out to inspect the damage and found her brother’s cap laying near the church.’

The stained glass windows by Heaton, Butler and Bayne were destroyed; the vicar cleared up the glass and threw it away, presumably not wishing to leave it as a reminder of the tragedy. Many years later, while cleaning, John Sired found a shard behind the reredos.

Today the ceiling of St Saviour’s chancel is a plain blue.

– Philippa Lewis