Ila Bêka & Louise Lemoine on the Moriyama House

– What is a House For and Bêka & Lemoine

The editors of ‘What is a House For’ (Mateusz Zaluska, Riccardo Amarri, and Matthew Bailey) have kindly allowed Drawing Matter to reproduce the following interview with Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine, in which the filmmakers discuss the Moriyama House (2005) by Ryue Nishizawa, the subject of their 2017 film ‘Moriyama-San’.

‘What is a House For’ is a research and online publication project initiated in 2020. To date, the editors have published 25 discussions on 25 houses chosen by figures from contemporary design culture. The project is international in scope, and publishes in three languages: English, Japanese, and Chinese (translations by Kou Matsumura, Keigo Mori and Jie Zhang). Find out more about the project on their website, and on Instagram.

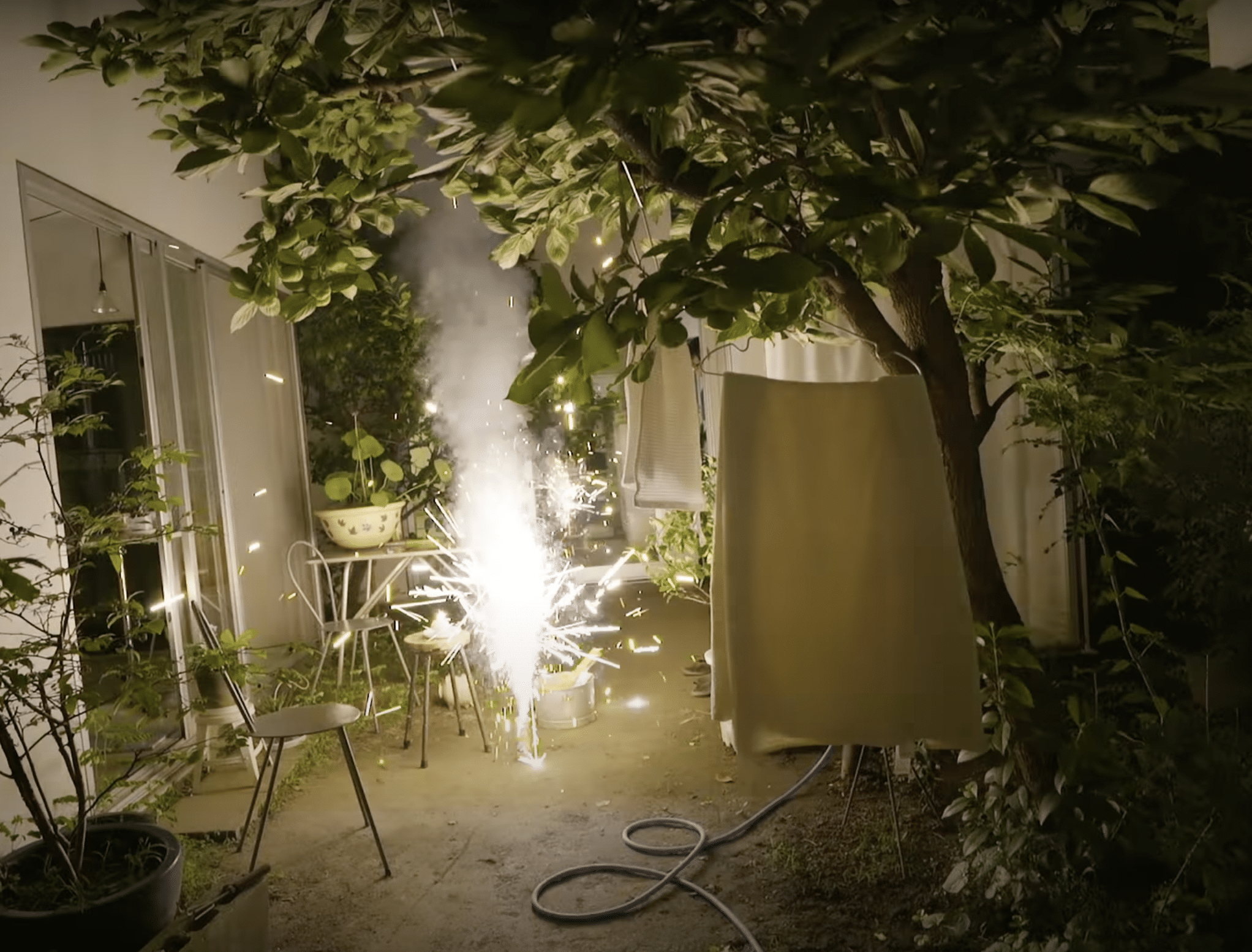

Ila Bêka & Louise Lemoine: For a significant part of his life, Moriyama-San worked from home in a liquor shop owned by his mother. When his mother passed away, he decided to demolish her house and the shop to build a new house, in the exact same place. He was up for the idea of putting himself into an experiment and wrote a letter directly to the architect Ryue Nishizawa believing he was the right professional to challenge his former way of life. Moriyama-San and Ila became friends through a common interest in Japanese noise music; that’s how Ila could stay with him in his house for a week during the summer of 2017.

How was his life before?

The original house, if we understood well from what Ryue Nishizawa told us, didn’t have windows as such, as they were completely covered with shelves, filled with books. It was compact, closed, and rather dark. Building a new house for Moriyama-San was in some way building a new way of life for him. He changed radically from a sort of a nerd, living in a dusty and slightly stifling environment, to a wild cat in a little urban forest.

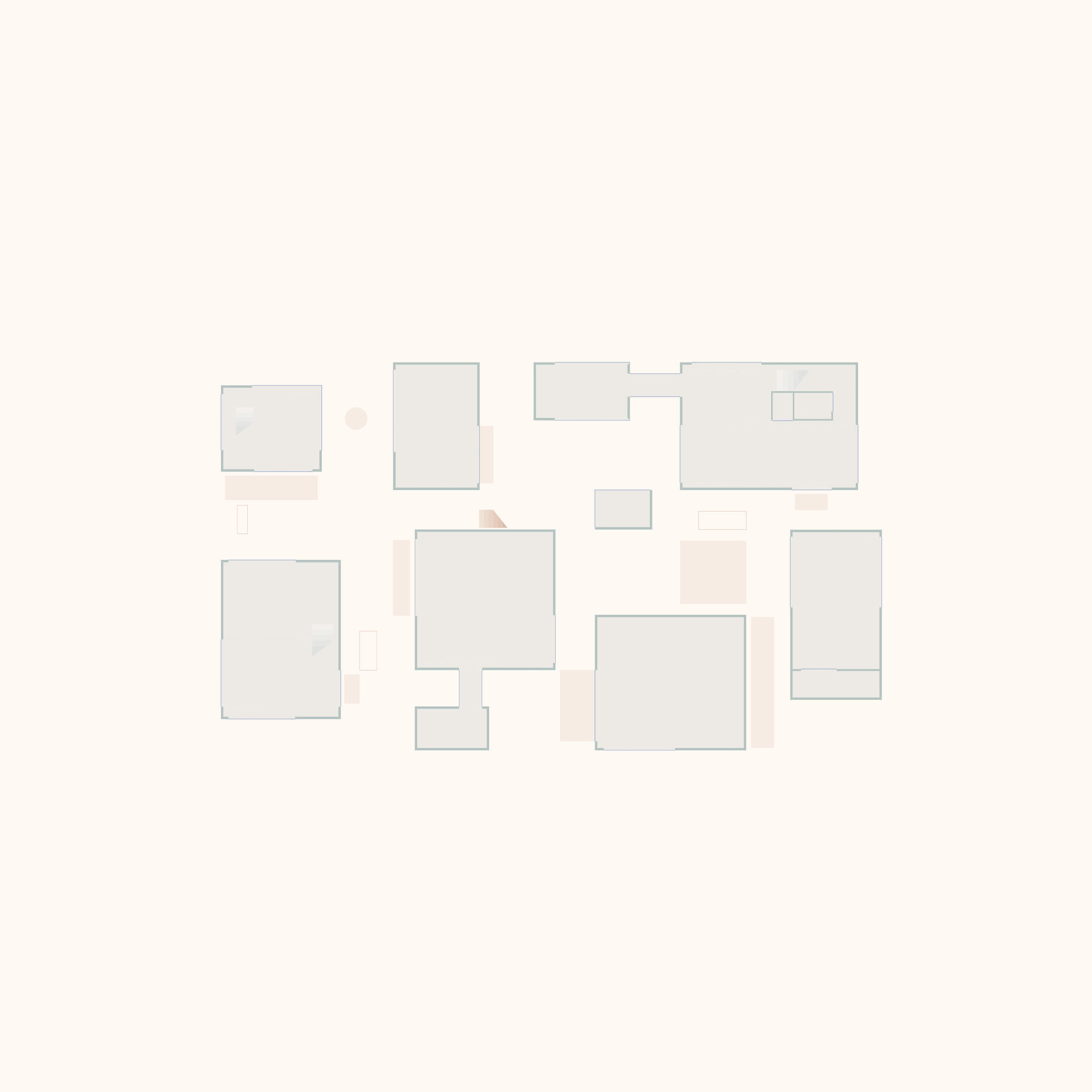

Today, his domestic life is divided between separate living units spread over the small site. Some of them are only one floor, some have stairs that lead to higher levels. Some have some spaces underground as well. The house pushes him to move up and down and between the cubes in the open air, regardless of rain, snow, or wind. Every time he uses the kitchen or bathroom, he must step outside. This fragmented organisation of domestic life constantly provokes unconventional and surprising situations. What in a more standard house would be considered as a living room—that is to say a central space unifying individual and isolated rooms—is assumed by the small central garden. So, it’s the outside which plays this unifying role among small units.

Being there, did you feel protected, or rather exposed to the city?

In the film ‘Tokyo Ride’ that we shot with Ryue Nishizawa, he evokes in a particular way how differently the Japanese and Westerners behave in regard to the idea of protection or exposure of the self in society. Westerners usually build their identity on the principle of individual strength. They need to seem powerful and prepared for a social relationship perceived as a conflict. Even if they can behave in very cordial and diplomatic ways, they are constantly, even if unconsciously, envisioning the social interaction as a potential confrontation in which hierarchies of power are at play. On the contrary, Nishizawa presented the Japanese people as ‘disarmed’, in the sense that they are not moved by such a pressure of conflict in relation to one another. You can strongly feel this in the almost total absence of aggressiveness in Japanese cities. I am not fully sure it can also explain the appeal towards transparency in contemporary Japanese architecture, but it would be interesting to investigate this further.

On this point of protection or exposure in architecture, we have also been really amazed to understand how Japan deals, in general, with thermal insulation. Because of their hot and humid climate, traditionally they have conceived an architecture of porosity—to allow natural ventilation within a building. What is very surprising is that even today this idea of thermal porosity remains. Walls are often thin, fragile even, and when inside, you feel closely connected to the outside in terms of either temperature or sound. So, it means that in winter you get very cold and very hot in summer. But this is also related to a larger fascination and respect towards nature and its strength in Japanese culture.

It’s a very interesting question, because it relates to the cultural rules defining privacy and respecting others.

The question of privacy is essentially a cultural definition which is understood very differently from one country to another. For instance, when we were in Copenhagen shooting a film in Bjarke Ingels’ 8 House, we experienced another variation on this paradoxical idea of ‘exposed intimacy’. Because of the lack of natural light during winter months in Denmark, there is a high preoccupation with light, people there have big windows with no curtains. In the evening, as a passer-by, you could see everything happening in the house, the most intimate family gatherings, people in their bedrooms, etc. The Moriyama House is very similar in this aspect. It is also built with huge openings, which merge the inside and the outside. It works well, because both in Japan and Denmark the culture is based on a high level of mutual respect. You see people passing by, neighbours on bikes, in cars, children running, old people walking, stopping, and so on. It’s an all-day sort of continuous flow but no one is supposed to peep in. The only ones who actually do, even in rather rude ways, are foreigners—as Moriyama-San recounted to us. To avoid this, he has placed a board on the street, written in English, asking architecture tourists if they could kindly avoid stepping in the private area of the garden.

Despite the transparency of the large openings on the street side, the intention of Nishizawa was to slightly separate the owner from the city, and to create—thanks to the central small garden—a peaceful protected place. This has been achieved, but just in a very balanced, idiosyncratic way. You are neither cut off nor completely exposed. You always have a choice, and it gives a very pleasant feeling.

In Europe, when we think about a connection or harmony with nature, usually we imagine buildings made from natural materials. The Moriyama House is a series of abstract white boxes. What effect does this have?

In this case architecture is a device to connect you with nature, but not necessarily a part of nature itself. The materials are not meant to have any rhetoric meaning or tell explicitly a story of belonging linguistically more to the garden rather than to the street. The house is minimal and left without any symbol of luxury, in order not to distract you from its main purpose. In terms of furniture and facilities, it offers the minimum Moriyama-San needs to live. For instance, the kitchen is used mainly to put beers in the fridge—but not to cook large meals for many guests or even himself. The house does not have what we would call a bedroom either, which, in truth, is extremely radical as sleeping on the floor was quite an experience.

In terms of our way of understanding a house, this house, as you put it, is a series of cubes, little rooms and angles that are dedicated to enjoying space and the present moment. It is not a technical device to answer all our needs or a manifestation of an ideology. It all works in such a simple and minimal way. Beyond its domestic functions, the house is a place to experience the emotions produced by the subtle interaction between the space, the garden and the movement of people passing by.

Why is a house an interesting topic for a film?

We figured out very early that most films on architecture were basically descriptive, focusing on the buildings’ aesthetic features, the materials, the structure, the various innovative features, etc. In a way, an architecture film often serves the specific role of being a promotional and communication tool for architects, and that necessarily induces a certain aesthetic with a sense of seduction in the way you make a film. In opposition to that, we have been looking to distort the relation of subordination between film and architecture, in order to find a real critical freedom which could open up a debate about how architecture is being represented. Film allows us to question the relationship we develop as human beings with our surrounding space. That’s why our main effort has been in placing people at the forefront of architecture’s representation to question architecture, its role and impact, from a more anthropological point of view. This led us to choose the house as the most interesting narrative device, because there is no other space we fill with more emotion, memories, and intimacy. The house is as much a spatial reality as a mental territory. This psychological richness made us understand that it was an endless reservoir of personal and moving stories.

Is ‘Moriyama-San’ a film about the house or about the person?

We’ve always tried to avoid filming the figure of the owner or the architect because they are usually excessively involved with the project, in an emotional way. They are acting, like in a theatre, and are rarely able to have sufficient distance to talk about the building in a natural and un-staged way.

Moriyama-San was an exception from the rule. He does not represent what we would call the typical pride of an owner that we see in Western culture. Moriyama-San was incredibly natural, and detached, breaking all clichés about the owners of buildings that are recognised as architectural achievements. What’s marvellous about him is that he seems essentially interested in his house for his pure personal enjoyment, that’s quite unique.

The idea was to talk about the space through the way it is being lived and experienced: so very much about the physical and psychological interaction with space. Rather than talking about the qualities of a space in an abstract way, we like to explore those qualities through the sensorial and emotional relationship an individual will create with the space he inhabits. And Moriyama-San is exceptional for this. It was a revelation for us. It was probably the first time we were so closely and intimately immersed within a sensibility very new for us, so subtle, so refined in its attention to micro atmospheric phenomena and so many aspects we rarely pay attention to in our busy urban lives. In many moments of the film, you can understand that Mr Moriyama moves through the house, chooses where to sit, to lie down or to stay depending on the qualities of light, sound, wind, temperature, etc. His way through the building is led by this sensorial intuition rather than by functional necessities. It was such an enlightening encounter for us. We learned so much from his ultra-sensitivity. It reinforced our conviction that the best way of recounting a space is through a fully immersive and intimate experience, and this is precisely what cinema allows us to do.

What experiences were you exposed to in the Moriyama house?

The scale of the house was very surprising. All these spaces are very small. You must physically adapt to enter them and move in a very precise and delicate way. It calls for a sort of physical dialogue with space like a precise choreography, otherwise you may bump into everything, knocking down objects and furniture upon each move. So, you must be extremely careful of how you move and where you step, because the house is also quite dangerous, there are no fences or railings. There are holes and large openings, a very small ladder, etc. So, it’s a sort of physical playground requiring you to be in a constant state of alert. The house proposes a kind of sensory kaleidoscope where each place offers different conditions and requires different types of awareness.

The first feeling, as occidental adults, was that our bodies were deeply maladapted as we are more accustomed to large spaces. We are not used to mastering our movements in such a precise way, to fit to the small dimensions of a Japanese house. We felt physically massive and a bit rough in the way we behave, so being there involved undergoing a sort of re-education of body language. From childhood, the Japanese are trained to adapt to the constraints of small scale and are thus much more measured and in control of their movements.

So, you understand the truth of a space by watching how someone exists in it?

Rather than ‘truth’ I would say more its inner qualities. This intuition also became the direction we gave to our teaching at the AA, where we led a master studio entitled ‘Laboratory for Sensitive Observers’. This course intended to introduce students to the ‘art of seeing’, in developing tools and methods to increase their skills of observation. The aim, on a larger scale, was to develop their sensitivity and understanding of the cultural features legible in our social behaviours, but also political and economic forces that are at play in our urban life. Our intent was to raise awareness on how important the quality of observation and the sharpness of a site analysis, in the complexity of its socio-cultural and historical components, is what will make the students’ future proposals as young architects more accurate and relevant, with a strong human sensitivity.

Do you think the capacity of observation is in danger nowadays?

We seem to live in an era of acceleration. There is great time pressure on the need to produce, to be very efficient and go straight to the point. There is, perhaps, less value in the idea of taking stock, thinking what-is-what, and spending time understanding something for ourselves. We also saw this in our students, who are very motivated to produce forms or to reach a goal but less interested in—or unable to—linger on something, to wander. They try to quickly achieve something, whatever it is. And this acceleration goes together with a reduced attention and availability to what surrounds you.

We also live in an era of total fascination with technology, which is sometimes crazy. If you think about the last 20 or 30 years, we are witnesses to an incredible change brought about by technology. We have the internet, space tourists, social media, none of which existed before. Now we believe we can change the future, the city, and the world with technology. This is certainly true, but perhaps it’s not the only possible and not necessarily the best way.

What are your observations about the way Moriyama-San lives in his house that could be lessons for us in the West?

We were amazed to see that he continuously explores space in different ways. He loves changing place, even, for instance, according to the subject of the book he is reading. He reads one or two pages and after that he decides where to go to best fit the next episode or chapter. It’s something that we should also do in our own spaces—move furniture, change the arrangements, go to the corner that we never go to, regardless of the reason.

One or two years ago, a student from Mendrisio made a film about how he and his flat mates used the space inside their house. He recorded the movement of everyone, three people, and used the data to make a ‘space use’ diagram. It showed that out of all the available space, they were using only 40 percent. He decided to change the layout of furniture to push the three people living there to use more space. After the experiment, he recorded their movements again, and his new diagrams showed that they used 75 percent of the area. It shows that most of us have in mind a conception of space that has been prepared for us. But if you try to explore, as Moriyama-San does, you can learn and discover a lot.

We believe young architects should be more prepared to put into question what we inherit in terms of socio-cultural patterns in the way we understand the domestic space. We have so many stereotypes of how a house should be organised, lived, and inhabited, with very specific functions and ways of behaving in certain spaces. It requires an effort, a conscious decision to say: ‘we want to disrupt all those patterns and introduce a certain degree of freedom’. It requires strength to go against what you consider right or not. You need to go back in time to when you were a child and forget what you have been told your whole life. A child always uses things in the most surprising ways, whether it is a chair or anything else related to space. A child will try to explore, to transform things into something to play with as he or she is still totally free from any cultural conditioning.

How can we be more like Moriyama-San—how can we be more sensitive observers?

We have a son; he is just four years old. One day we asked him: ‘Do you like your bedroom? Do you like the position of the bed?’. For him, at that moment, it sounded like a very strange question. We provoked him to think about the space of his most intimate daily life. He said: ‘yeah, but why do you ask?’. We said, ‘We could change it if you want. We could put the bed at the other end of the room, in the other direction so that you could look out of the window in the morning, see the birds or the moving clouds’, he said, ‘oh yes, that is a good idea’. We moved his bed.

Some days later, he came and told us that he would like to put the bed back like it had been before. We asked why and he answered that before he could see the door from where we entered. So, what happened in this very moment is that he started to think about the meaning of how his personal space was organised. He realised that he felt more secure, more comfortable when he could see his parents coming into the room. This is incredible. If you were to teach this to kids at school, with exercises of this kind, for instance changing the layout of their bedroom, they would start to be conscious of space—to be aware of what a spatial experience is. One day they would go outside into the city, when they are twenty years old or more and say that they cannot live in the city because it is not good, that it must be fixed. I think this is a topic that unfortunately is underestimated. If we could introduce from primary school that kind of questioning, to develop collective awareness regarding the physical organisation of space and its psychological and emotional consequences, it could make a big difference.

In this respect, Moriyama-San is an incredible example of a person who has maintained what we would call the innocence of a child. He is not trained or structured by any cultural patterns of domesticity. He is the sensitive observer and participant in space that we search for. We can say that living with him, we were exposed to all the things that we try to theorise about during the making of our films. We can find them all in him.

What we learned from him is his subtle degree of presence, an intensity in the way he lives in the present moment through all his senses. As rational occidental adults we tend to forget this state of openness, which in our culture would be associated with innocence—too much is lost through our own social conditioning. But we should be careful not to forget too much.

– fala