Charles Barry: Good and Bad Manners in Architecture

Architectural manners are […] known by a quality which money cannot buy, and which can lend distinction not only to the greatest building but to the smallest.

T. A. Edwards, Good and Bad Manners in Architecture, 1924, Preface, vi.

There is often an elegance in architectural simplicity that goes unrecognised by the casual observer. Such simplicity is hard-won. Charles Barry’s masterly junction between his Travellers and Reform Clubs is a prime example, and one which I have long admired.

Whilst at the British School at Rome (1980–82), with a taste for the architecture of Barry, I became increasingly aware of the importance of well-considered, well-mannered, architectural junctions, irrespective of scale and medium. The corner, angular, junction of columns in a temple, a courtyard, or a hall, were obvious marks of good architecture – and invariably an all-too-evident fudge by the also-rans. Regardless of style – classical, gothic or modernist – the abutment of materials, the projection of mouldings, and their union with one another and wall planes, spoke volumes.

Looking at the works of the nineteenth-century ‘Nobs’ of English architecture, junctions confirm the quality of men, such as Cockerell (for the most part), and the paucity of others, including Nash and Smirke. Throughout his career Barry displayed sensitivity to mouldings; their scale, finish and juxtaposition. Never was this decorum more put to the test than in 1837, when he faced the unusual challenge of competing to build a new club-house, the Reform, next to his own work of the same species on Pall Mall: the Travellers Club (1830–32).

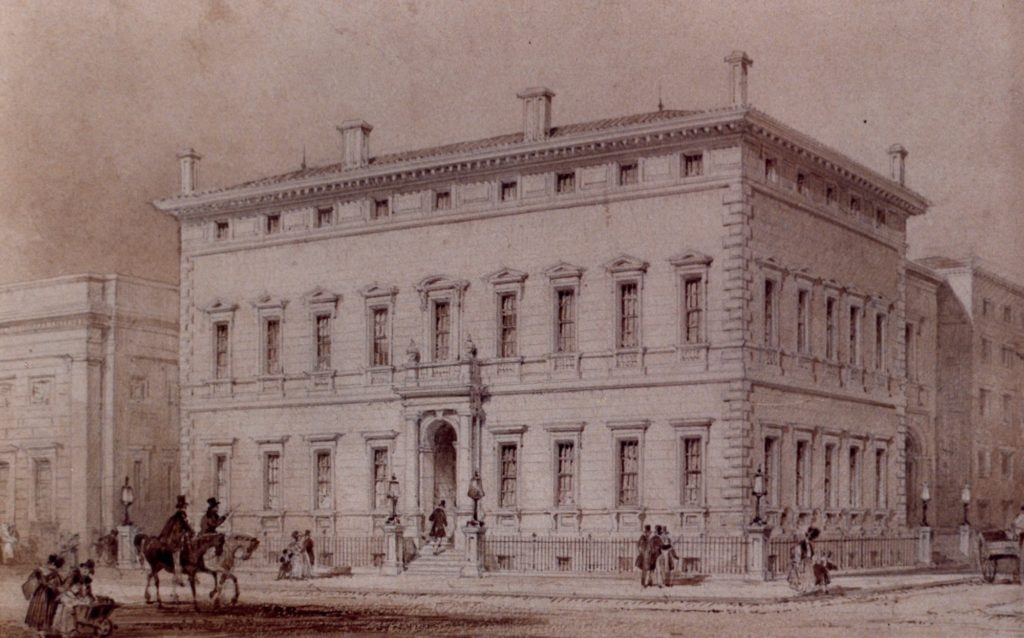

Here, Barry had to confront the dilemma of style. Could such a grandiose Italianate Reform palazzo – which the ambitious committee clearly want to surpass all other clubs in size and magnificence (especially, with resentment, unaccommodating Brooks’s and its more rakish illiberal Whig aristos) – sit well next to the comparatively diminutive, simple and elegant, even homely, Italianate palazzino Travellers. There was also the important issue of how to form the union – the junction – between the two…

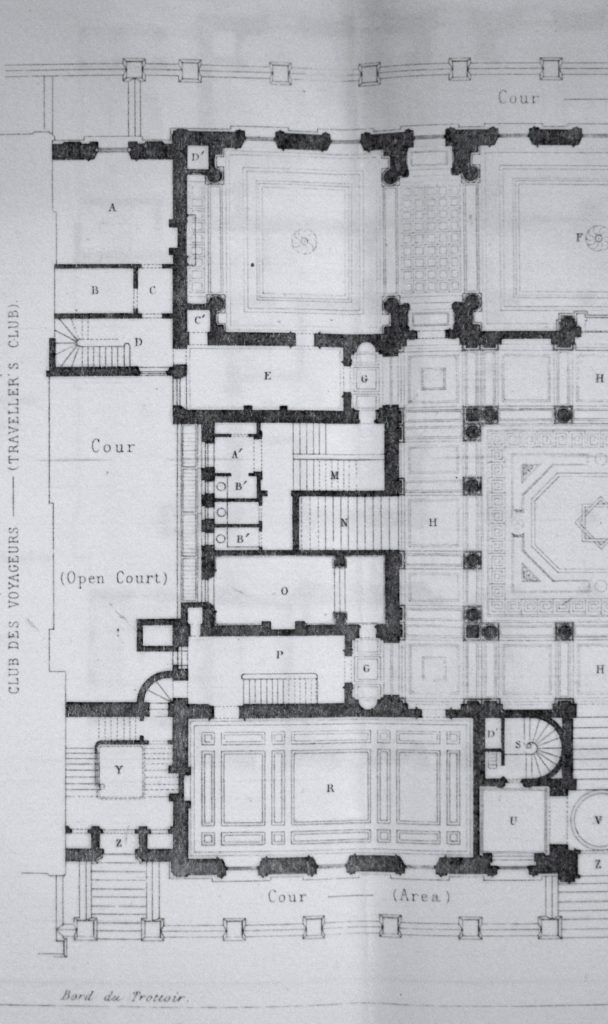

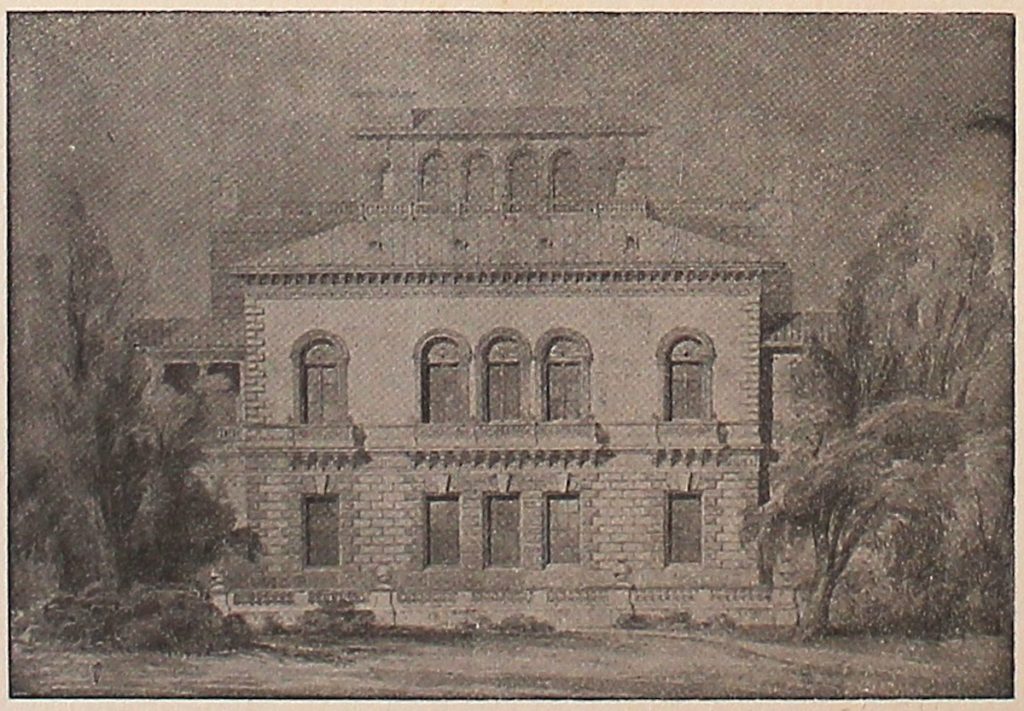

Having, after much debate and restless, agitated sketching in various ‘modern’ Italianate vocabularies to contrast with the Travellers, Barry settled on ‘cold cabbage reheated’. The columnless, astylar, style of the Travellers was, after all, to be repeated. But the Reform would be in a style and plan echoing the august Roman High Renaissance – Palazzo Farnese – which, on Pall Mall, would contrast with the more demure Florentine – Pandolfini – and, on the garden façade, Venetian, Travellers. Besides, the notion was not new to him; the previous year he had designed a prototype of such a palazzo for Manchester: the Athenaeum (1837–39), next to his Anglo-Greek Royal Institution (1824–35). Having generally resolved the plan of the Reform about an open, colonnaded, cortile – a feature he longed to introduce – and which on his competition drawings he labelled Italian court, Barry pondered the union between the pair of strikingly differing Pall Mall Italianati.

Determined to build a club-house surpassing all others in comfort, sophistication, and architectural splendour, the Reform Building Committee made life awkward not only for their architect, but the Travellers. The smaller ‘two’ storey Travellers, with its façade of only 74 feet, really could not be adjoined by such a massive ‘three’ storey neighbour as the Reform, with its potential frontage of 142 feet. Worse still, if directly abutting, the Reform’s proposed great corniccione would have projected, bullyingly, over its humbler neighbour. Not that this concerned the other Reform Club competitors; Cockerell included.

Moreover, so as to enhance the solidity, grandeur, uniformity and completeness for which Barry strove, all four corners of the Reform needed to be emphasised. To form a respectful separation, a gap, a passageway, as originally (fleetingly) contemplated, would have been ideal. But, even with such a large site, ground being precious, this diplomatic intercession could not be entertained.

Barry’s well-mannered solution, worthy of the strade of Rome and Florence, and one he was employing at Manchester between his Athenaeum palazzo and its George Street neighbour, is deceptively simple.

Given the projection of the Reform’s crowning cornice, a gap of about 15 feet was created, and then infilled, as if at a later date and with clearly contrasting door and window forms (semi-headed) and (modern French-inspired) mouldings to both its neighbours.

So as not to detract from Barry’s first love, this recessed symmetrical intervening compartment is significantly lower than the Travellers, and set back from the facades of both clubs. By this intervention, being recessed, with the first floor set back yet further than the ground floor, the Reform, when viewed from Pall Mall in perspective, appears to stand singularly detached; alone in its grandeur, without overwhelming the Travellers. There are also, due to this sensitive interjection, eastern windows to the ‘third’ storey of the Reform that would otherwise have been impossible.

Though this courteous infill, with its Portland stone facing detailing – as exquisite as the rest of the Reform – should give the game away, passing idly by some may ponder if this small independent-looking recessed infill edifice belongs to either club – or neither. In reality it was the street entrance and stairs to the Reform’s innovatory ‘lodging apartments’ for out of towners on the ‘third’ floor.

Behind this compact entrance and staircase of about 20 feet depth, was a small cortile of sorts – a light well of 45 x 20 feet – beyond which, on the garden side, was a block of about 33 feet deep, housing the steward’s room and a servants’ staircase, with above – and originally again set yet further back – a smoking ‘loggia’.

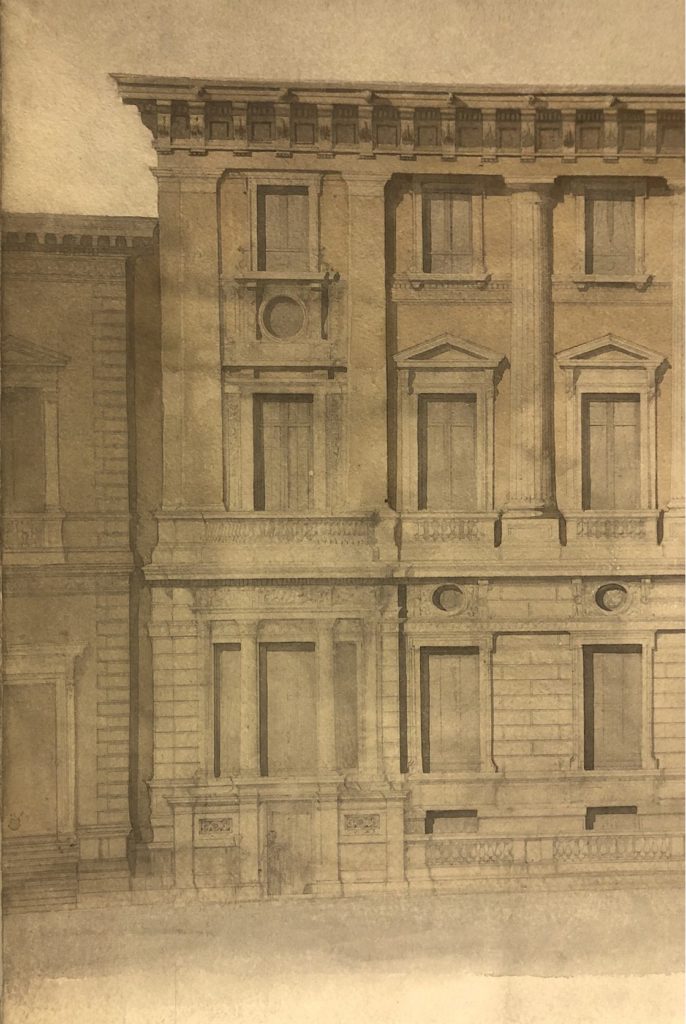

Barry’s rationale is beautifully illustrated by his diploma drawing for the Royal Academy depicting his idealised south-facing garden façade of his beloved Travellers Club. For, on the 10th February 1842, whilst finishing touches were being made to the Reform Club, Barry was (at last) elected as an RA. Here he illustrated the well-mannered interjection between his Reform and Travellers, and with relish – and by way of encouragement to its members – added a third storey belvedere smoking-room to the Travellers. Though this roof-top addition was executed in 1842-43, such had been contemplated by Barry as early as March 1829, whilst amending his winning Travellers’ competition entry, but had not then been executed by the Travellers on grounds of cost. Given his love of symmetry, and obviously wishing to show his Travellers in its best light, Barry also added to his RA drawing a fanciful, polite interjection between his Travellers and Burton’s Athenaeum; as, indeed, could have existed had the original competition site for the Travellers been adhered to, leaving no.108 Pall Mall standing (or better still rebuilt) between the two clubs. Thus, for the RA in 1842, Barry created the illusion, on paper, of his Travellers being a daintily free-standing villa, with rustic service wings, set in its giardino inglese with suitable garden balustrading, almost as if it were in the Veneto on the banks of the Brenta. A small copperplate of this splendid diploma drawing is also at the RA, and it was with a sense of fun that (too many years ago now) the then librarian and I took several prints from the plate; which clearly had not been used for many decades.

Though Barry exhibited such architectural good manners for the Reformers in joining himself to himself, and forming a visual buffer between them and the Travellers, due principally to the influence of two intransigent members, such was not reciprocated when, in Spring 1843, it came to his final 5% account of £3,933 on a total expenditure (including fitting up and finishes) of £78,682.4s.4d. Eventually, in August 1844, the arbitrator awarded Barry every penny claimed, plus his costs. But still under the strong pressure by two difficult members the club made ‘shuffling excuses for non-payment’ for their luxurious, technologically advanced palazzo masterpiece; which Macaulay told Leigh Hunt, was ‘worthy of Michel Angelo’, and which was hailed by the press as an ‘auspicious omen of reform in architecture’.

The Reform Club’s ill-judged reluctance to pay Barry did not go unnoticed. John Bull – a Sunday newspaper – had its fun, asserting on 12th October 1844 that the Whig-Radicals, ‘always famous for shabby expedients’, had devised a scheme to lighten their burden: ‘they actively repudiate the claim of Mr.Barry … for rearing their club-house (the reputation of which, as a building, has been instrumental in keeping the thing hitherto in existence) contenting themselves with the comfortable reflection that he ought to be satisfied with the payment of a little more than one-third of the usual professional charge, which in the exuberance of their liberality they paid him on account’. Barry did, however, eventually receive his cheque.

Despite this distasteful aberration on the part of the club, over the ensuing years they sensibly returned to Barry for help and guidance over internal alterations to their great Italianate palace.

Though fearing becoming his own rival, with his magnificent, modern Reform palazzo, full of wit and pleasing contrivances, Barry proved his supreme architectural confidence and his worth, as one of the ‘Nobs’ of architecture. Being still in his days of classic purism, he had again not only predictably rejected the use of engaged columns, but also – after some mild flirtation – the more novel, richer, dialects of ‘modern’ Italianate. Barry, not wishing to overpower the Travellers palazzino, an edifice that had ‘deservedly gained him so much credit’, the comparatively insignificant recessed insert between the two contrasting rivals is an important, indispensable, brilliant element of the masterpiece that is the Reform Club palazzo. Moreover, he had no wish to repeat the problematic negotiations he had experienced when designing the Travellers Club, with its neighbour, Burton’s Athenaeum. Barry’s deftness was not just architectural. To have antagonised the Travellers – some of whom were good clients, excellent promoters and friends – would have been foolish. The importance of such courteous work being well-conveyed by Trystan Edwards in his Good and Bad Manners in Architecture; still a seminal, though neglected, text for architects – and clients.