Charles Stanley Peach: Pioneer in Power

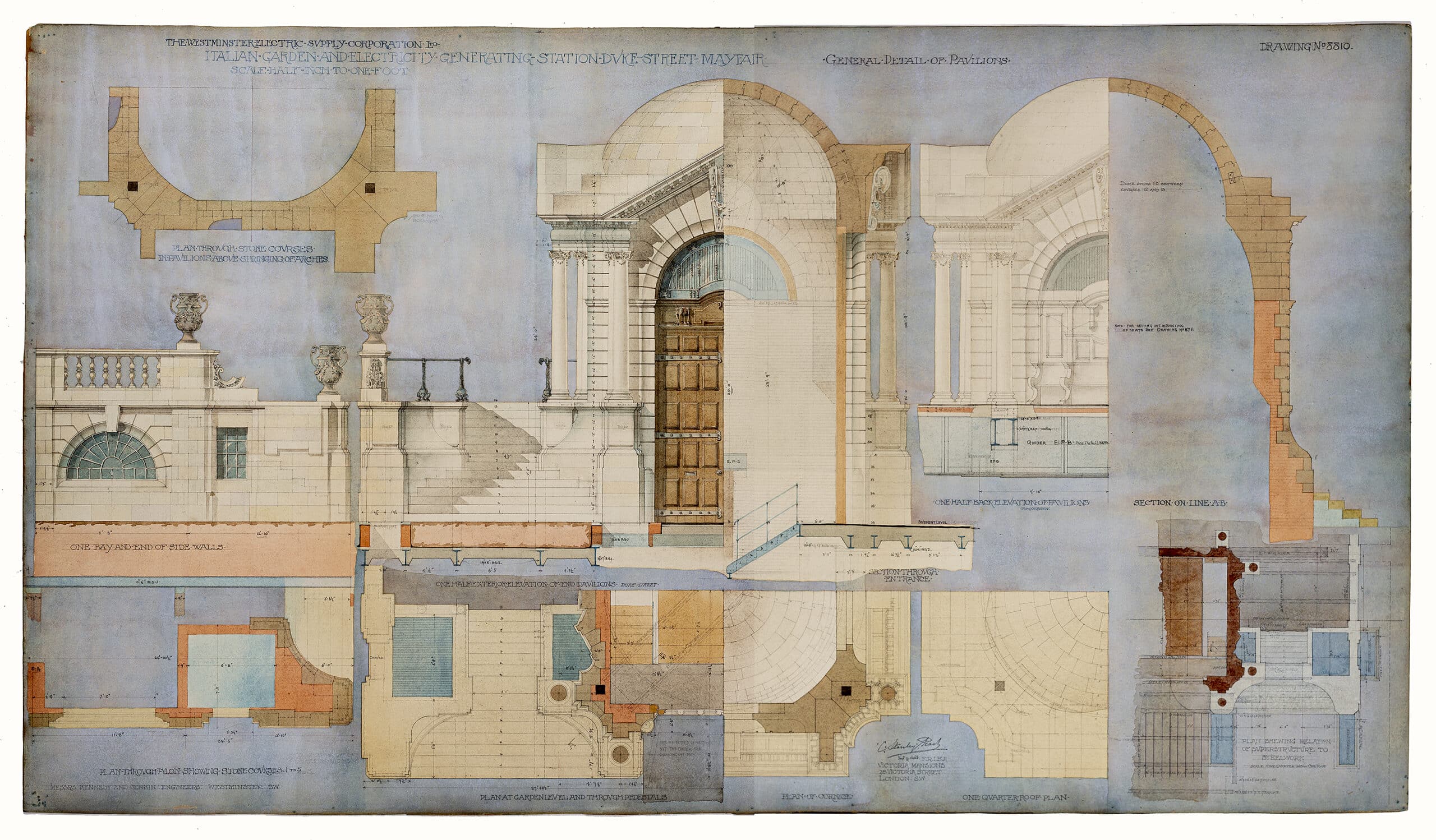

Charles Stanley Peach set up his architectural practice in 1884, just as the public’s access to electricity was established. Through his contacts in the engineering world, he became involved in designing power supply infrastructure, including Brown Hart Gardens, a substation and Italianate garden in Mayfair.

The following excerpt is taken from Andrew Jones’ article ‘Brown Hart Gardens: ‘Good Feeling Among the Neighbours’, published in The London Gardener (Vol. 25, 2021).

Charles Stanley Peach has been described as a ‘Pioneer in Power’. [1] Born on a boat returning from India, Peach began by studying medicine. After a year, he abandoned his studies and left for the Eastern Rockies to participate in a United States Government survey of a ‘country […] still wild and uncultivated and inhabited only by encampments of Red Indians, where now are large and prosperous cities.’[2] After a serious riding accident, Peach returned to England and spent two years (1882–3) in the office of architect Hugh Roumieu Gough, F.R.I.B.A.

Peach’s apprenticeship as an architect coincided with the beginning of public electricity supply in Britain. In 1884, when the 25 year old Peach set up his own practice, opportunities in the power sector were immense. The Electric Lighting Act 1882 had enabled the supply of electricity to the public by private companies and local authorities and, in the same year, Thomas Edison had opened the world’s first coal-fired power station at 57 Holborn Viaduct.

Peach knew many of the leading electrical engineers of his time, among them Ferranti and Crompton, and soon became the preferred architect for the numerous companies setting up electricity supply systems around Britain, completing around seventy power infrastructure buildings during his career.

In 1904, just as Brown Hart Gardens was nearing completion, Peach delivered a paper to the Royal Institute of British Architects, Notes on the Design and Construction of Buildings connected with the Generation and Supply of Electricity. [3]

The paper is a remarkable and comprehensive study of good architectural practice in the design of power and substations across the world (Peach had travelled widely in Europe visiting power infrastructure and corresponded with leading designers in the United States). Peach takes a keen interest in the mechanical and practical aspects of these buildings, in particular with regard to fire risk and vibration, and argues that while ‘the work of the electrician and the mechanical engineer [in the construction of a power station] is undoubtedly the most important,’ the architect must build ‘the frame [to] uphold, support, and protect the vital organs […] [and] give some suitable outward expression of the wonderful and useful work carried out within the structure’.

Relations with the surrounding community are critical to the success of these structures:

In designing these buildings the amenities of the locality should not be disregarded, and every care should be taken to reduce to the minimum all causes of nuisance or annoyance. The appearance of the building counts for much in these cases.

A small amount of additional capital expenditure can mitigate the risk of ‘hostility, expense and litigation’ leading to ‘good feeling among the neighbours, a more valuable building for the owners […] something to show that the people of this generation, while inheriting the commercial instinct of those who founded the Hanseatic League, have not lost the art of combining the useful with the aesthetic in the design of buildings of the warehouse class’.

The paper established Peach as an international authority and he became a consultant to France and Switzerland on their power station building programmes.

As well as building power infrastructure buildings, Peach worked on apartment blocks (including Crompton Court on Pelham Street), theatres (including the interior of The Theatre Royal, Haymarket) and the Lawn Tennis Stadium at Wimbledon, the largest reinforced concrete structure of its day when opened in 1921.

A most modern architect, therefore, but also a man who, after a day of designing power stations, would go on to work through the night on vast drawings of King Solomon’s Temple at Jerusalem (where he had spent a year trying to solve its mysteries), such as that now in the collection of Robert Simon Fine Art in New York (another version also in the RIBA Collection), or on imaginary pictures of Christ superimposed on the plan of a Church, now in the Drawing Matter collection.

Andrew Jones’ full text can be downloaded, or purchased in print, from The London Gardener website, here.

Notes

- J. N. Hill, Pioneer in Power. [source unknown; after 1934].

- E. Stanley Hall, ‘Obituary of Charles Stanley Peach’, Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, vol. 61, 8 September 1934.

- Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, vol. 11, issue 11, 2 April 1904.