The Destruction of the City of Homs

A photograph of the bombed-out shell of Dresden, destroyed in February 1945 when I was six years old, has lived potently in my life-long memory bank. This, like other black and white photographs of the time, depicted a ghastly desolation in which empty-windowed facades tapering sharply from jaggedly pointed upper stories to the debris-surrounded bases seemed to mimic the triangular infrastructure of the Gothic. A few pointed spires and steeple silhouettes in the wreckage of the city imbued the image with a profoundly melancholy pictorialisation of destroyed European history. The remains of the baroque dome and lantern of the bombed Frauenkirche somehow didn’t contradict this view of death and destruction as the shape of an erstwhile medievalism: sharply pointed, jagged and perpendicular.

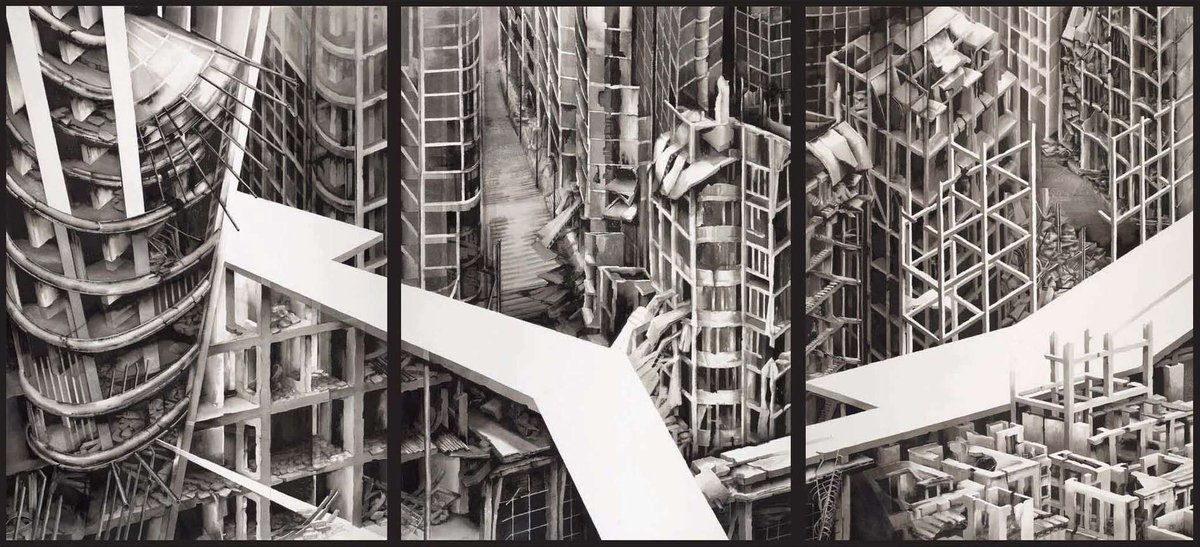

When I became sure that the destruction and suffering in the Syrian civil war was to be the demanding subject for a new drawing, I realised that the horrific images and descriptions haunting me in the media were those of the wreckage of a modern city. I have never visited Syria and never gone to Homs, but what shocked me in this new Middle-Eastern war was that I was seeing the total annihilation of modernity. As horrific witness to a different kind of warfare and means of obliteration, these were blunt not jagged ruins; not the serrated remnants of stone or brick shells but the skeletal remains of reinforced concrete structures. When contemporary utilitarian architecture loses its glazed curtain walling and its flimsy infill panels and divisions it reverts to a hollow imitation of its original post and platform structure.

For me, there is something very freakish and diabolical about this reversion. If we assume that our bodily architecture is the model for the visual formal imagination of the structures of beginnings and endings, that is birth and death, then the ondos should be profoundly different from the telos. Here on the other hand the eradication of the finished has returned itself to the preparatory infrastructure for that final state, rendering all the aspiring stages of the in-between null and void. I can see that some other more benign philosophical interpretation could be wrested from this uroboric enchaining, but in trying to find a visual language for depicting The Destruction of the City of Homs, I could only perceive the incinerated city as coldly and chillingly empty: a clumsy pile of vertical and horizontal debris voided of the living future and the lived-in past.

The city I have drawn could, of course, be Aleppo. As it is not based on fact – only partly suggested by photographs and film and mostly invented – I realised that the name ‘Homs’ was significant to me for another reason. To a Western ear its name relates to the French l’homme and its extension, as a term for mankind… perhaps even humankind.

This is a symbolic work, but it still demanded that I drew every inch of its surface with an immense attention to detail, as if, by so doing, I could commemorate all the imaginary people and their activities: the office buildings, the factories, the mosques, the schools and hospitals, the homes, apartments and workshops and their bombardment to rubble and dust. The city – and there are lots of towers still standing in my drawing but they are all empty – is drawn from a multitude of viewpoints, as if I was traversing its geography on the back of a drone. I have viewed it from above, below and within, sometimes recording a perspective, sometimes a worm’s eye view, sometimes an oblique projection, sometimes large in scale sometimes small, but all with the same level of detailed depiction. There is no rationality or consistency in the multiplicity of views, although held together (I hope) by the similitude of the ink and wash technique. For me, the gaping diagonal white passages tearing through its complexities represent those awful bulldozed wound-like roads that cut through destroyed urban areas during wars. No matter who or what was there before, now there is only a brutish urgency to move army troops over and through the archaeology of destruction. Rubble is not cleared for those starving ghosts surviving amongst the ruins but to support the passage of the conquering armies to move on to further slaughter.

This was my thinking behind the triptych, which could be augmented on every side as it doesn’t have a beginning or end and the framing is entirely arbitrary. I cannot, of course, assess whether it does convey to the onlooker any of the things that I was thinking when drawing it over a period of eight months. Drawn thoughts often have a very different impact from the self-consciousness of a written exegesis. I fear that my being wrapped in the horror of thinking about war, suffering and refugee misery hasn’t necessarily translated into significant imagery, but I hope that the drawing has some resonance about the desolation and futility of war.

We suggest: Deanna Petherbridge, The Destruction of the City of Homs, Tate Britain. The work is on display in 60 Years, curated by Sofia Karamani in the Walk Through British Art Galleries on the main floor until April 2020.

Deanna Petherbridge’s solo exhibition will ran from 2 December 2016 – 4 June 2017 at the Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester.

Deanna Petherbridge: Drawing and Dialogue, featuring essays by Deanna Petherbridge, Gill Perry, Roger Malbert, Martin Clayton and Angela Weight, is available from Circa Press.