DMJ – Borromini’s Smudge

This text, published alongside Bernhard Siegert’s article ‘From Landscape to Mapscape: Robert Smithson’s Maps’ marks the launch of the first and second issues of DMJournal–Architecture and Representation. Over the coming months, we will be publishing articles from both DMJ 1: The Geological Imagination and DMJ 2: Drawing Instruments/Instrumental Drawings. The Geological Imagination will be published in print in early 2023.

In lieu of a world of geometrically well-defined solids,

let us imagine a world of pasty objects.

Gaston Bachelard, Les Intuitions atomistiques (1933)

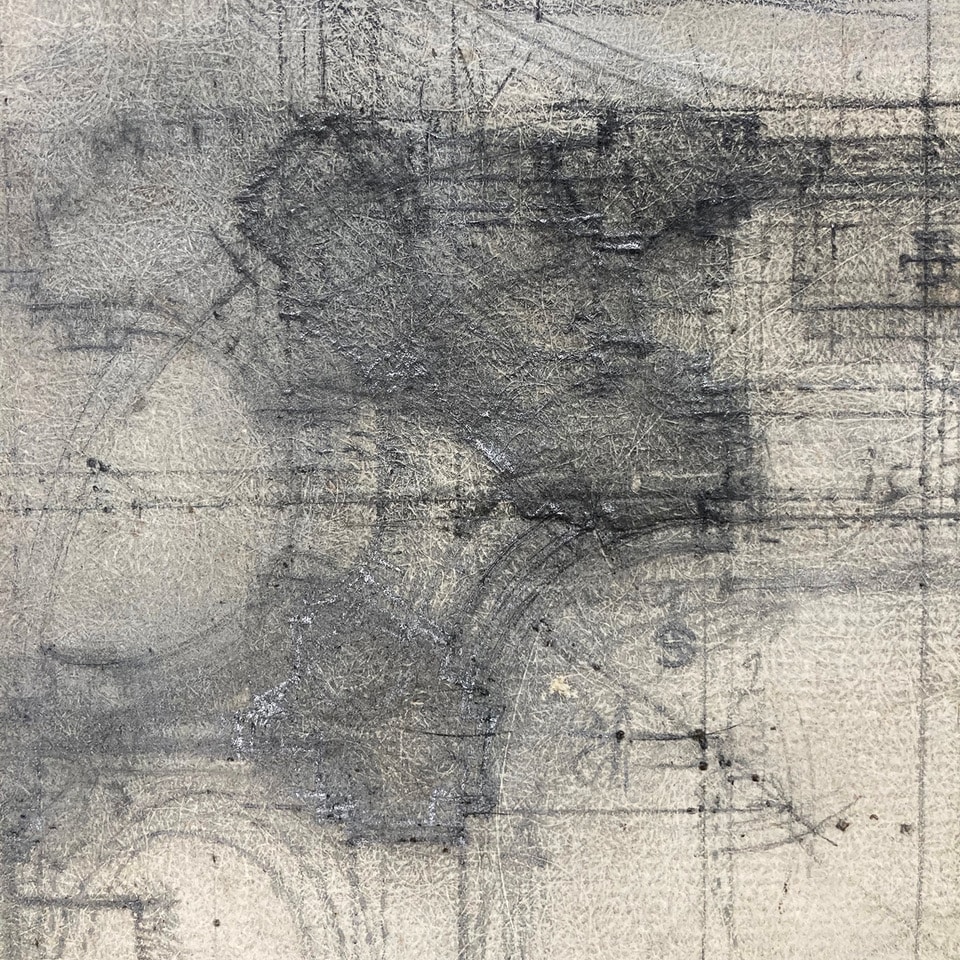

There is a drawing in the Albertina in Vienna by Francesco Borromini (1599–1667), made late in life for the Cappella dei Re Magi in Rome, which is so overdrawn and compressed with a graphite pencil that in some areas the paper is creased into a pulpy contusion. This is only the beginning. Passing deeper into the collection reveals sheet after sheet of smudged plans, smoked-out elevations, blackened sketches, beclouded details, and a confounding display of fuzzy, hazy and obfuscated graphite marks. The Ticinese stone-cutter-architect was already known during his lifetime as a compulsive drafter, but the sustained intensity of the way he wielded his graphite cannot be seen as merely accidental.

Graphite was in Borromini’s time a new drawing material, which hardly anyone else in Rome was using. Hard, crystalline and able to be brought to a sharp point, it left a resolute and penetrating mark that could be smeared or erased, yet it adhered well to textured drawing surfaces. Scholars have generally understood Borromini’s smudgy graphite marks as by-products in the progression from rough to precise geometrical resolutions – the teasing out of form from formlessness, a theory of creation inherited from Giorgio Vasari. It has since become commonplace to analyse Borromini’s plan of San Carlino, for example, by extracting a rigid framework of lines, arcs and circles to discover the underlying geometric apparatus, hidden, as it were, by a cloud of dust. Indeed, if you play a word association game with an architect and say ‘Borromini’, the chances are that, after the knee-jerk ‘baroque’, the word ‘geometry’ will quickly emerge.

Mentally peel away three to five centimetres of bone-white stucco finish from one of Borromini’s interiors, and an alternative reading of the drawings becomes possible, one that takes into account his remarkable use of building materials. To construct walls and vaults, Borromini utilised recovered bricks, a material known as tevolozze. Unlike new bricks, which are characterised by an intrinsic logic of seriality, regularity and modularity, tevolozze drew upon the variability of the brick fragments’ orientations to enable the making of highly plastic or malleable wall constructions. This heterogenous amalgam of thick mortar and broken bricks was then covered by stucco romano, a mix of lime and marble dust acquired from antique statues and pulverised building fragments.

The material dialectic between tevolozze and stucco romano provided the material support for Borromini’s signature approach to light and space. This technique emerged directly out of Roman building culture, with its long tradition of re-use and relation to antique methods. The inherent anti-modularity of chipped and broken bricks, along with the ‘pasty’ stucco covering, offered new possibilities in the architectural potential of details and surfaces. In his graphite productions, Borromini’s way of working – with its repeated overdrawing, pressing, smudging and smearing – produces a result that resonates with his plastic approach to broken brick and stucco. It furthermore suggests material sympathies between the graphite dust and other kinds of particulate matter imagined in the building process, such as dusty matter in the air, or the fine, white powders produced for the stucco.

Placed together – smeared graphite and supple wall materials – Borromini’s approach to shaping and profiling offers surprising readings and stands in stark contrast to the idealised geometrical schema through which he is normally framed. Graphite was a critical tool for not only evaluating the visual aspects of a building but also for initiating them in the process of construction. As a multi-sensorial phenomenon, involving both vision and touch, the graphite smudge played upon the analogy between drawing materials and the materials of building in order to anticipate experiences and practices to come.

DMJournal–Architecture and Representation

No. 2: Drawing Instruments/Instrumental Drawings

Edited by Mark Dorrian and Paul Emmons

ISSN 2753-5010 (Online)

ISBN (forthcoming)

About the author

Jonathan Foote, Ph.D, is an architect and Associate Professor at Aarhus School of Architecture, Denmark. His teaching, editorial work and research focuses on the relation between architectural drawings and materials, as well as the relation between architectural history and workshop-based knowledge.

Foote has published on the drawings and workshop practices of Michelangelo Buonarroti, Francesco Borromini, and Sigurd Lewerentz. These intersections between the workshop, teaching and academic work have led to a number of international exhibitions and externally funded creative projects. He also leads a design research studio, Atelier U:W, which partners locally and internationally on special projects in design and fabrication.

Click here to receive updates about the journal, and future calls for abstracts.