Drawings of Architectures

Primitivo González Collection

– Primitivo González and Niall Hobhouse

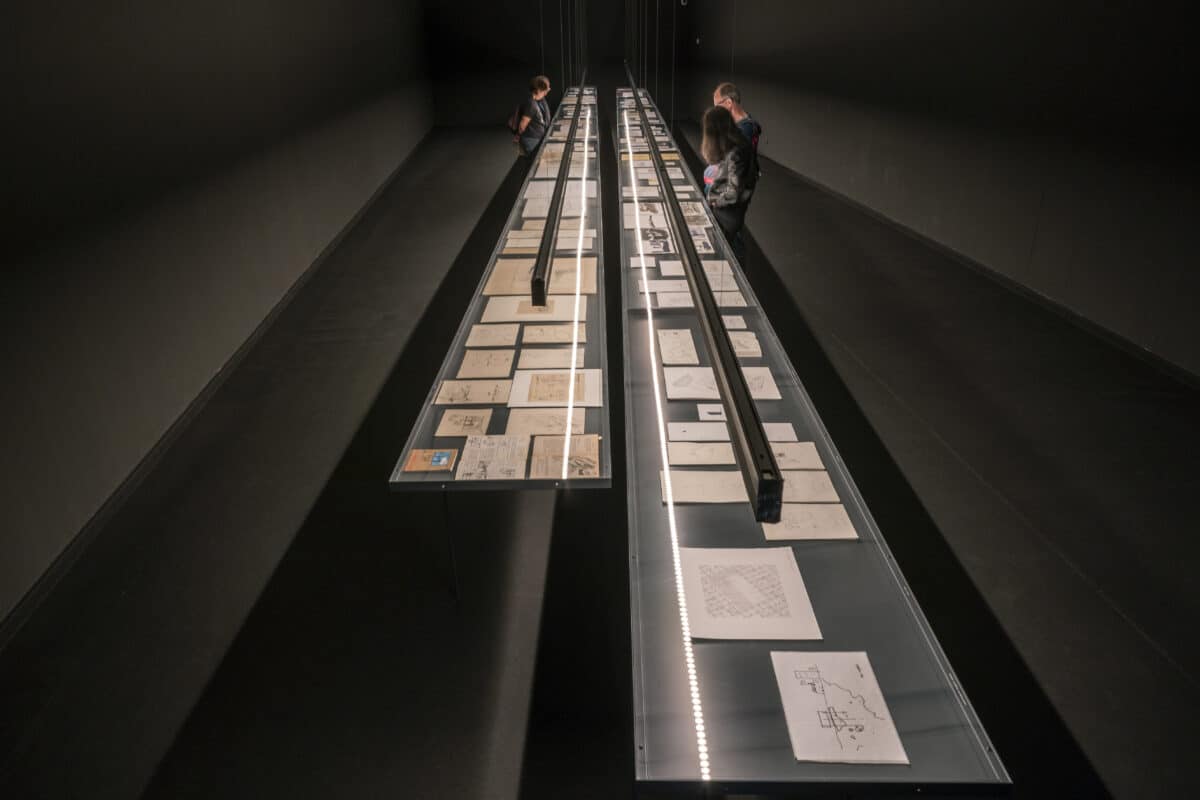

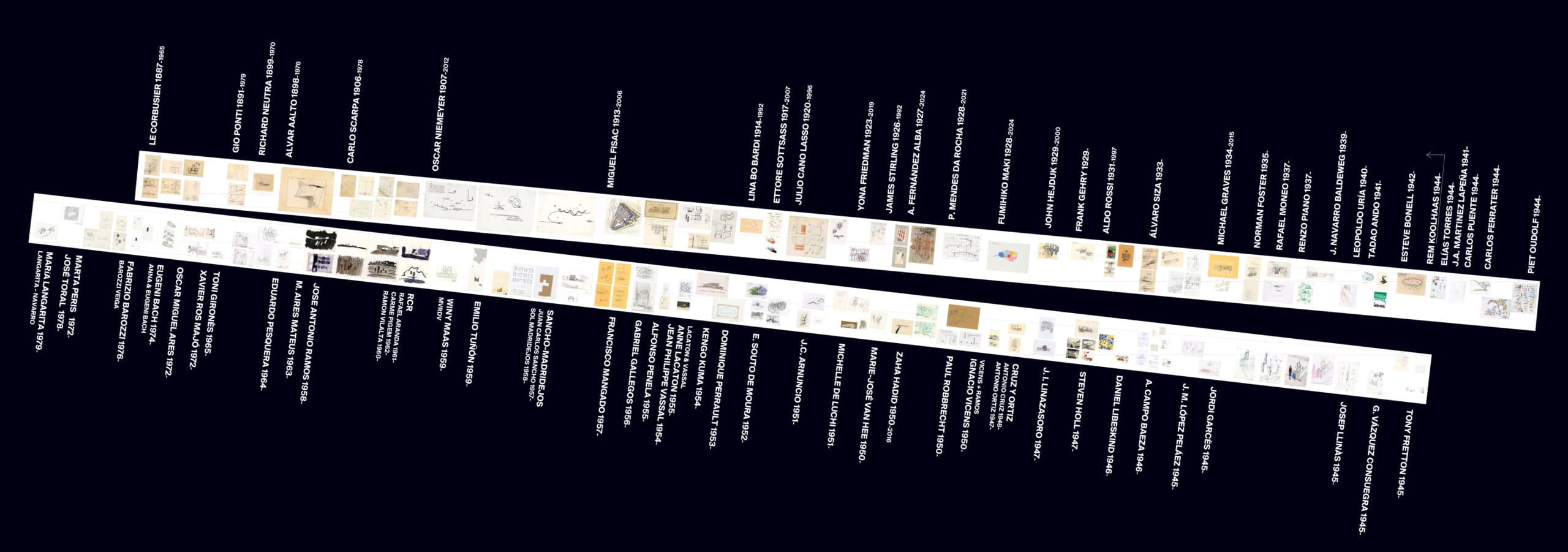

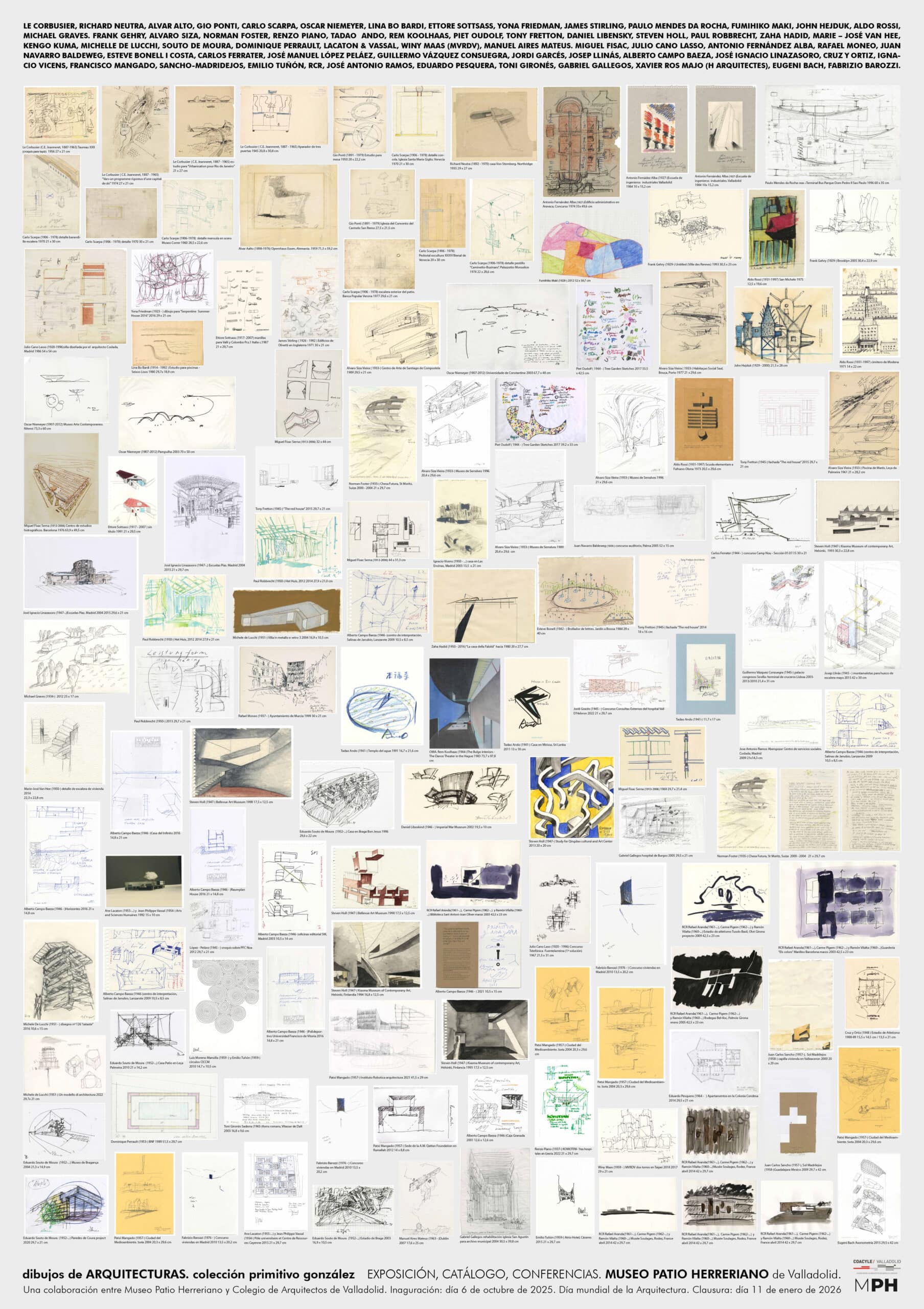

The exhibition Drawings of Architectures brings together Primitivo González’s private collection of original architectural drawings, sketches and notes, which González has been collecting for more than twenty-five years. The exhibition, designed by Ara, Noa and Primitivo González, includes drawings from Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto, Rafael Moneo, and Emilio Tuñón, among others, and is presented at the Patio Herreriano Museum in Valladolid until January 18, 2026. This is a collaboration between the Patio Herreriano Museum, the Valladolid College of Architects, and the Primitivo González Studio / e.G.a. architects.

González’s interest in collecting architectural drawings is not driven by a search for specific pieces, but rather by a desire to trace the moment when different architects first give shape to their ideas. Neither the signature nor graphic perfection is as important as the dialogue between multiple thoughts. The drawings in the collection enjoy a dual status: they are the beginning of a design process, and at the same time, works of art with their own value. Each drawing is part of a broader map: a cartography of modern and contemporary architecture, traced from fragments that reveal the diversity of ways of designing.

The short text by Niall Hobhouse that follows was prepared in anticipation of the opening of the exhibition.

A hundred mistakes?

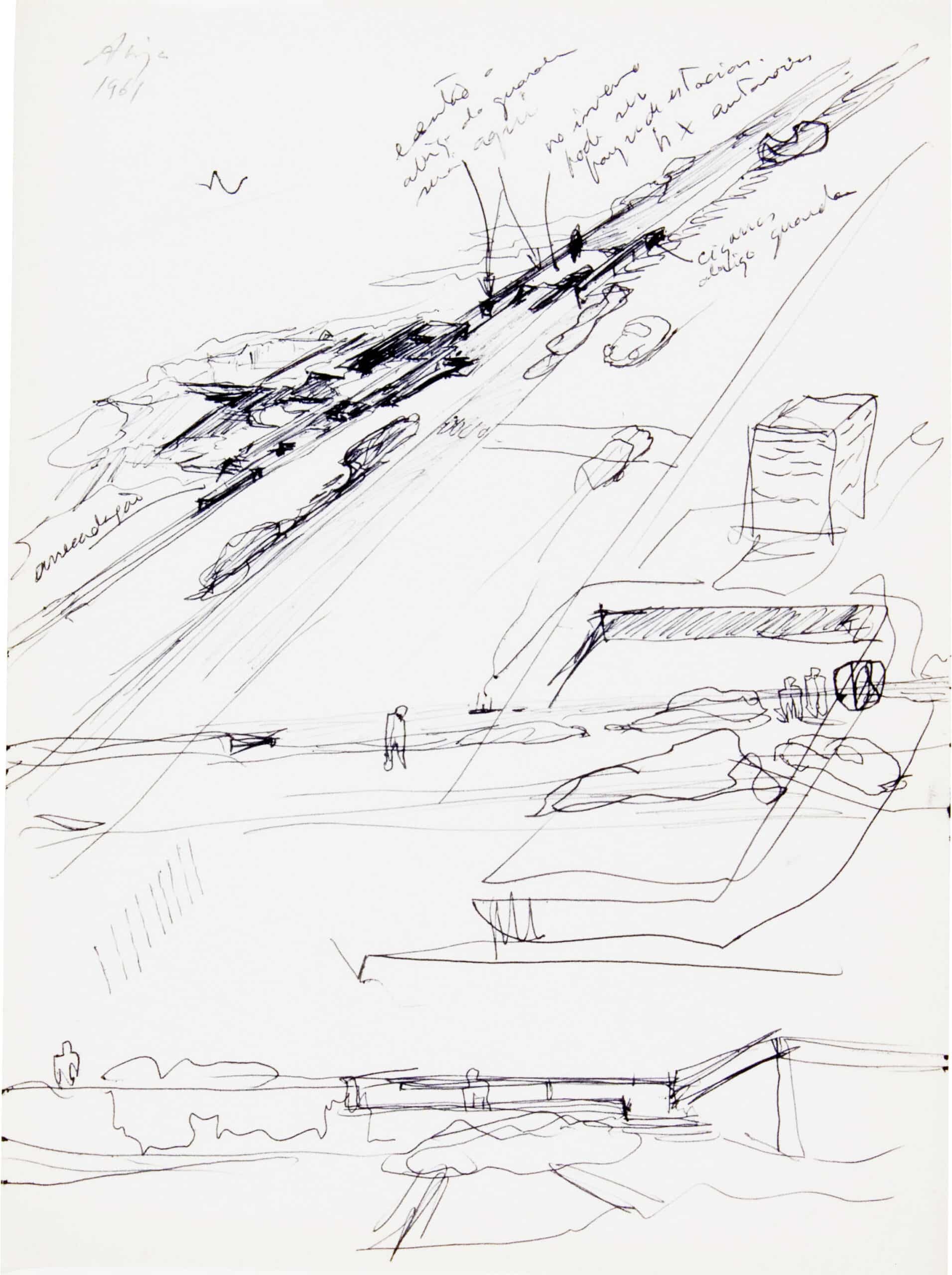

‘There, now you have a hundred of my mistakes,’ said Alvaro Siza, as he parted with the earliest of his sketchbooks from 1977, for the Malagueira housing project.

Possessed with the urgent need to capture or represent an idea, architects strain the limits of every convention, technique or technology then available; it is this frustration—this tension, indeed, between concept and expression—that produces the powerful disegni and ultimately, of course, the good buildings. By this logic, there can never be such a thing as the perfect drawing tool—but only the continuing search for one.

In the meantime, the endemic imperfection of mark-making by hand, on whatever sheet of paper is available, remains the reasonable default.

Everyone who becomes involved in the later processes of curation—the museums and other collectors, historians, the architects themselves—is obliged to operate within this uncertain terrain, and they have often done so by misleading their potential audiences about the true status and intellectual value of the architectural drawing.

In the first place, it becomes almost impossible to establish a standard of quality without the finished building for comparison or, at the least, a clear narrative of the original purpose of the drawing—thus privileging the representations of built work over the radical and conceptual. The architects are almost always complicit in this. Their professional priority is to project certainties, with the greatest possible clarity of expression. A sequence of scruffy sketches might best describe their imaginative process, but will never satisfy a client or the museum public. Here, we might add a warning that the prevalence in the last fifty years of the production of the ‘first’ conceptual sketch, from the hand of the great master, is often a wilful attempt at distraction.

By default, museums collect the presentation drawings that most closely resemble the finished building, often understanding that their role is to exhibit ‘architecture’ alongside painting and sculpture, rather than to explore the intimate process of its design. By contrast, historical archives assemble the technical drawings preserved by the practices themselves, which, by documenting the details of construction, offer a happy playground just for monographic historians.

Between these two poles, there exist many drawings that can tell us far more than buildings themselves—or, indeed, than their dry archival trace: about the original thinking of the architect, about how ideas evolve within the design process, and collaborative practices in the studio. It is this over-(under-)looked material—rich, diffuse, ephemeral and often hard to categorise, which yields most when examined in the original and not in reproduction; above all, it has most to offer students and practitioners as a resource for the production of better architecture.

There is no substitute for Siza’s ‘mistakes’; we do, perhaps, need to find a better word to describe them.

*

Primitivo González, studied architecture at the University of Barcelona and holds a doctorate from the University of Valladolid. In 1978, he founded his own studio in Valladolid. In 2014, the studio was restructured with the incorporation of Noa and Ara González, forming a practice based on the experience accumulated over forty years while embracing a more flexible and diverse approach to architectural projects.

Niall Hobhouse is the Director of Drawing Matter; he collects drawings by architects, curates exhibitions and writes about buildings, landscapes and museums.