Eric Gill On Designing War Graves (1919)

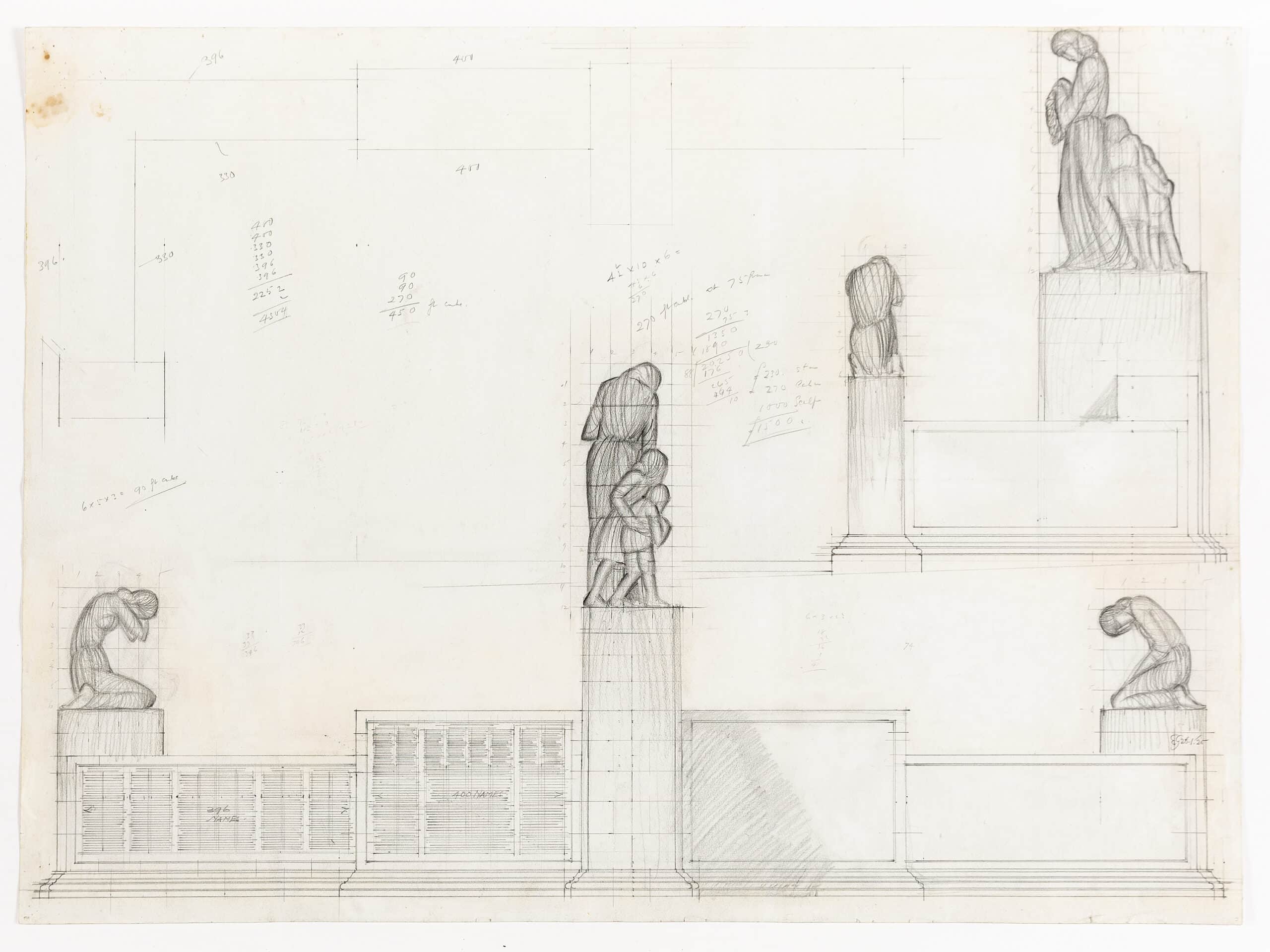

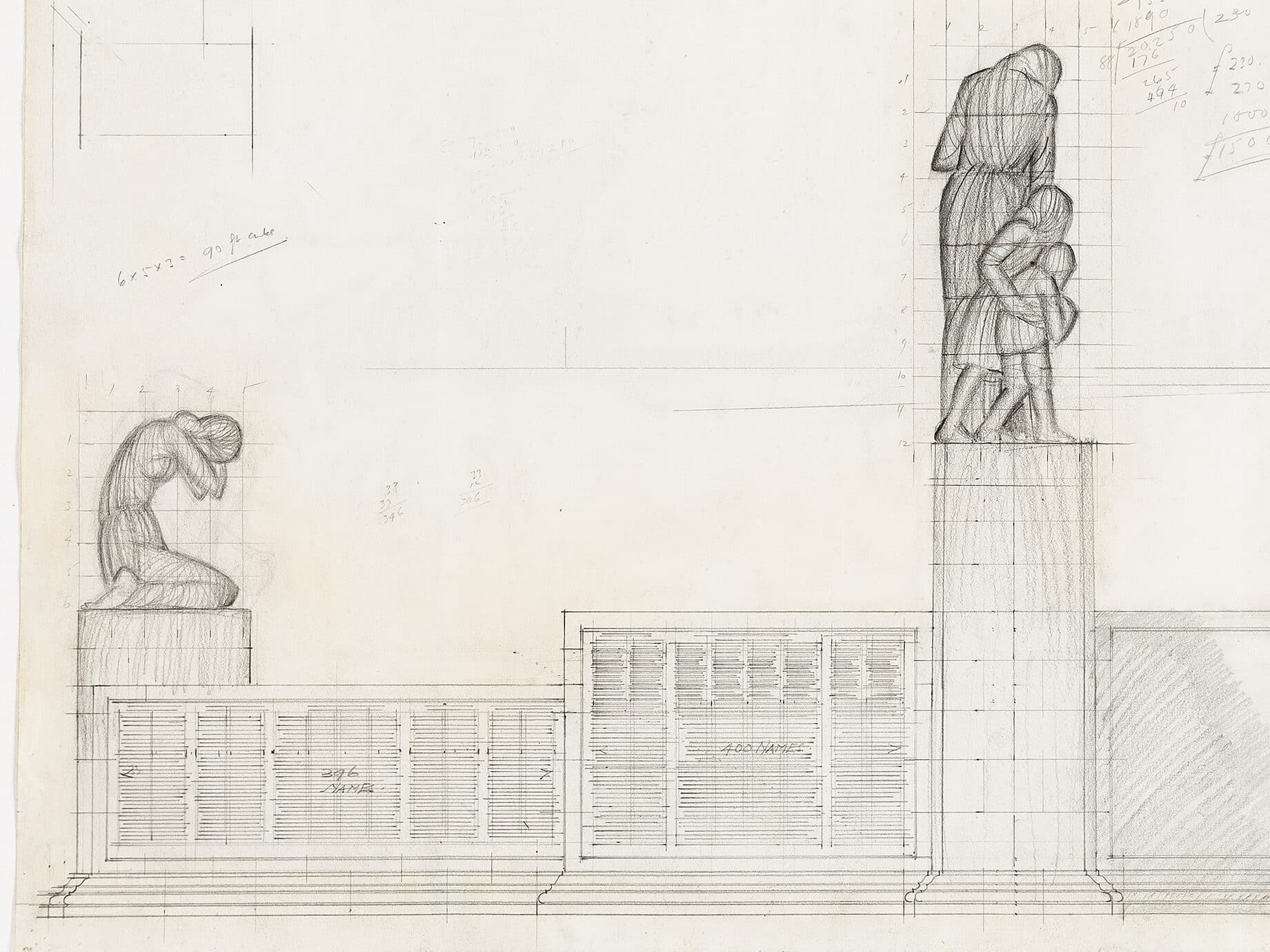

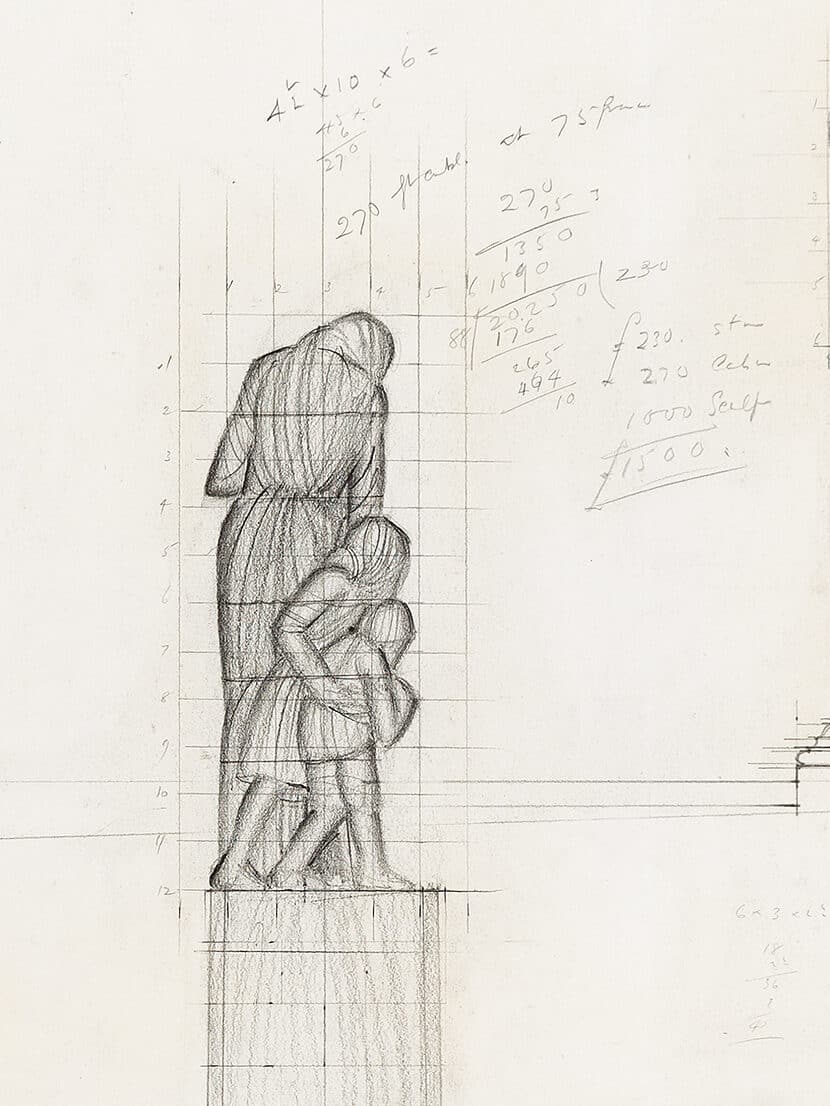

In 1918, when the First World War ended, Eric Gill was in his late forties and completing the Stations of the Cross for Westminster Cathedral. He was soon in demand to design and sculpt war memorials. Gill would create simple memorials listing the names of the fallen for both the Victoria and Albert and British Museums. His most ambitious memorial stands in the centre of the town of Trumpington, Cambridgeshire, dedicated in 1921. This design for a memorial, the location not identified, would have been Gill’s largest commission of the type. It is truly an architectural work as opposed to even the Trumpington Memorial, a large cross with relief sculpture on each of the four sides; it shows Gill’s understanding of architectural form, a result of having trained as an architect in the office of W.D. Caroe.

Gentlemen, Sir Frederic Kenyon’s report to the Imperial War Graves Commission calls for public protest. [1] We are all aware that to be effective such protest must come from the millions of men and women whose sons and husbands and fathers are buried in foreign lands, rather than from any body of specialist opinion. I am, however, convinced that something will have been gained if the government’s proposals can be discredited upon technical and artistic grounds alone. In the first place, and generally, it seems clear that the principal mistake is the placing of the matter of war graves in the hands of architects. Architectural advice is possibly desirable, but leadership by architects in such a matter is a mistake on two grounds, viz. : 1. The provision and erection of monuments, whether central monuments or headstones, is the principal business under discussion, and this is not an architect’s job, but a sculptor’s and a tombstone-maker’s. 2. The architect is, by the nature of his profession, one who directs the work of builders – he is not himself a maker of things. The designing of monuments is properly the business of those who make monuments.

In this matter of war graves there is, upon the one hand, the department of government concerned, viz., the Imperial War Graves Commission, and, upon the other, there are the various classes of workers and makers of things, among whom we are here only concerned with those who make monuments.

The business of the War Graves Commission is, in this matter of monuments, to decide what form, if any, the national or central monuments shall take, having regard, not at all to the artistic views of architects, but solely to the sentiment of the nation, poor as well as rich, if ascertainable, and to the funds at its disposal. If it should decide that headstones should be placed upon every known grave (i.e., if it should conclude that such is the nation’s wish, and the French or other foreign governments, mirabile dictu, do not object), then it is its business to ascertain and declare the number of headstones required, and, calling together a representative body of headstone-makers (small firms rather than big, because the heads of small firms are generally themselves working masons and not merely business managers, how- ever cultured by acquaintance with architects), to discover the best method of production.

This method has not been followed by the War Graves Commission, which, impressed, as most people are at the present time, by the commercial success of organised production and, probably, quite ignorant, as rich people generally are, of the evils resulting from modern industrial methods, naturally allowed itself to be led by architects – the artistic counterparts of business managers.

This would be the less deplorable were it not that the making of tombstones is still in a very large degree in the hands of small firms which, scattered up and down the country (there is probably hardly a town without a small mason’s yard), are quite capable of supplying all the head- stones or crosses required, and that in a manner which, if not up to the artistic level of former times (and that cannot be expected in an age concerned more for the volume of international trade than for the good quality of the product), would certainly have the merit of being representative of the national culture or lack of culture, and not representative merely of the ideas of a few individual architects.

The commission’s attitude in the matter is the more easily understood inasmuch as it is the whole. trend of our time to impose the ideas of the few upon the many while being careful to hide the process under a guise of democratic sympathy and social reform. Thus the idea that half a million headstones should be made according to the ideas of a few architects (an idea worthy of the Prussian or the Ptolemy at his best) instead of according to those of several thousand stone- masons and twenty million relatives is not surprising, and under the plea of commemorating ‘the sense of comradeship and common service’ and ‘the spirit of discipline and order’, etc. (vide ‘Report’), it is hoped that the very widespread desire of relatives to have some personal control of the monuments to their dead will be overcome.

If the graveyards in France and elsewhere, and the bodies buried in them, are the absolute property of the government (a legal question as to which I am ignorant), then the wishes of relatives need not be considered, and the government has only to discover how best to provide, if such be its desire, a permanent memorial, and, if only from that point of view, the idea of erecting over half a million headstones from the designs of a few architects stands condemned, for, by such a method, nothing will be commemorated but the ineptitude of a commercial nation blind to the fact that good workmanship is a personal achievement and cannot be ordered, like coal, by the ton.

But few successful architects, still less men of business and administrators, can see the truth of these contentions, and the hypocrisy becomes appalling when, on the strange contention (vide ‘Report’) that ‘we are a Christian empire’, it is proposed not only to put up crosses as central monuments but even sham altars. The central doctrine of Christianity is the freewill and consequent responsibility of the individual. Yet here is a nation calling itself Christian which refuses responsibility to the workman, and under the cloak of culture denies to mourners even the unfettered choice of words! (vide ‘Report’.)

I assume that the administration decides that any known grave shall have a headstone (whether or no this is really desirable or desired).

I assume that the administration has the right, and it has the power, to make certain regulations (we are not anarchists) as to the size of headstones.

I assume that the administration has not the right, though it has the power, to enslave, intellectually, morally, aesthetically, or physically, even one man, and certainly not a very large number of men.

I assume that, provided certain regimental particulars (name, date, regiment, etc.) be inscribed upon each stone, the administration has not the right to dictate to relatives as to what shall or shall not be inscribed upon the stone, and this in spite of all that may be said (vide ‘Report’) about ‘the sentimental versifier or the crank’.

Now, an ordinary small monumental mason could, without turning his shop into a factory, easily and without hurrying, supply, say, six hundred small headstones in three years at the cost of a few pounds each (say between £3 10s. and £5). Presumably a thousand other small workshops could do the same, and it would be desirable and seemly to distribute the work so that, as far as possible, the stones commemorating men of a certain locality should be made in that locality – Brighton masons doing stones for Brighton men, Marlow for Marlow, and so on – placing the work always in the hands of ‘small’ men and not big firms.

In this way a certain local quality would result, and the graveyards would gain the desirable quality of variety. Anything in addition to the regimental particulars could be paid for by the relatives and not by the government. What would it matter if the lettering and mason’s work varied between one stone and the next – some good, some bad? That variety would be better than a uniform mediocrity, however quasi-artistic (vide Postscript to this letter). Why should not the inscriptions be as varied as the men they commemorate – some good, some bad? If we are, as we are, a nation without a strong tradition of good workmanship, why hide the fact under a pretentious scheme of architectural origin as do the Prussians in Berlin?

It is suggested in Sir Frederic Kenyon’s report that the rows of headstones will be like a regiment on parade. But a regiment on parade is, though uniformed, not composed of men all of one size and shape and colour and kind.

It is said that the existing wooden crosses are very impressive, and they well may be. But they were not made all at one time by the thousand from the design of an architect! A crowd in Trafalgar Square is very impressive; but if you were to replace it by an equal number of tailor’s dummies it is not certain that the result, however architectural, would be equally impressive.

In conclusion, I would urge that the government should take the advice of those who have some respect for individuality and responsibility instead of that of persons whose whole outlook is coloured by the notion that good work can be produced by proxy. – I am, yours faithfully,

Eric Gill.

P.S. – I understand that, for the actual doing of inscriptions, the government is employing several architects and assistants to experiment with a process by which acid shall be used to ‘bite’ the lettering into the stone. Even if the result were not bound to be a failure upon artistic grounds (as all methods must be which have their origin in the desire to save money), and it is, to say the least, unlikely that the repetition upon many thousands of headstones of the same rather feebly artistic lettering (we have seen specimens), made more or less worse by the acid process, will be a success, it is clear that such a process would never have been thought of if the government were not inspired by quantitative rather than qualitative notions. If a single firm should have the job of turning out 600,000 headstones, naturally it would cast around for cheap and quick processes, and it is, I think, not the least merit of the counter proposal suggested above that the temptation to sacrifice quality to quantity would be reduced to a minimum. A man who has got three years in which to make six hundred small headstones has (provided the payment be reasonable) no need to hurry himself, and he can put his best into the work – always supposing that he is himself a workman and not merely the master of other workmen with no interest in the work but the profit to be got out of it. – E. G.

Letter to the Burlington Magazine, published April 1919.

Notes

- War Graves. Report to the Imperial War Graves Com- mission by Lieut. -Colonel Sir Frederic Kenvon, K.C.B., Director of the British Museum (H.M. Stationery Office, 3d. net)

From the collection:

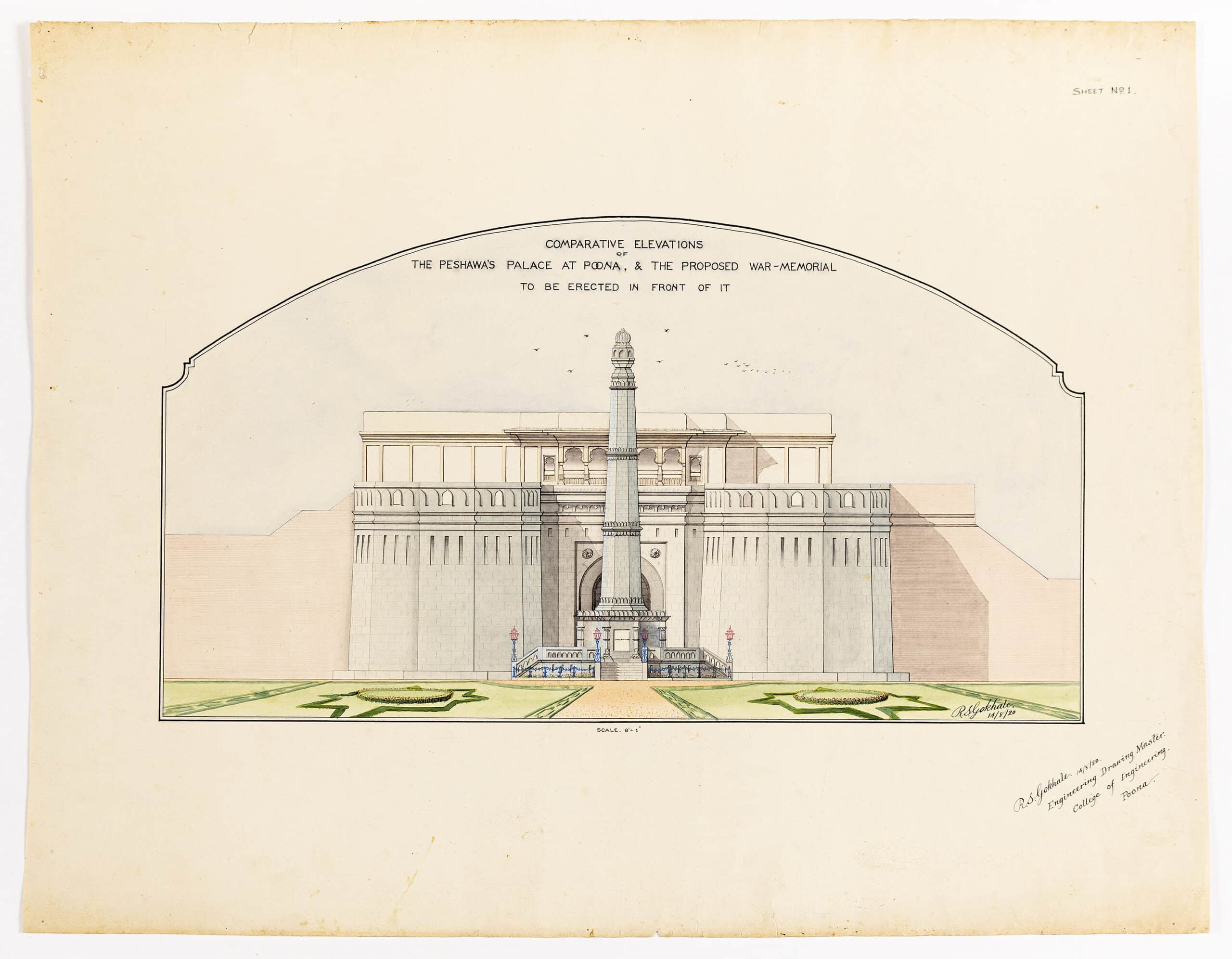

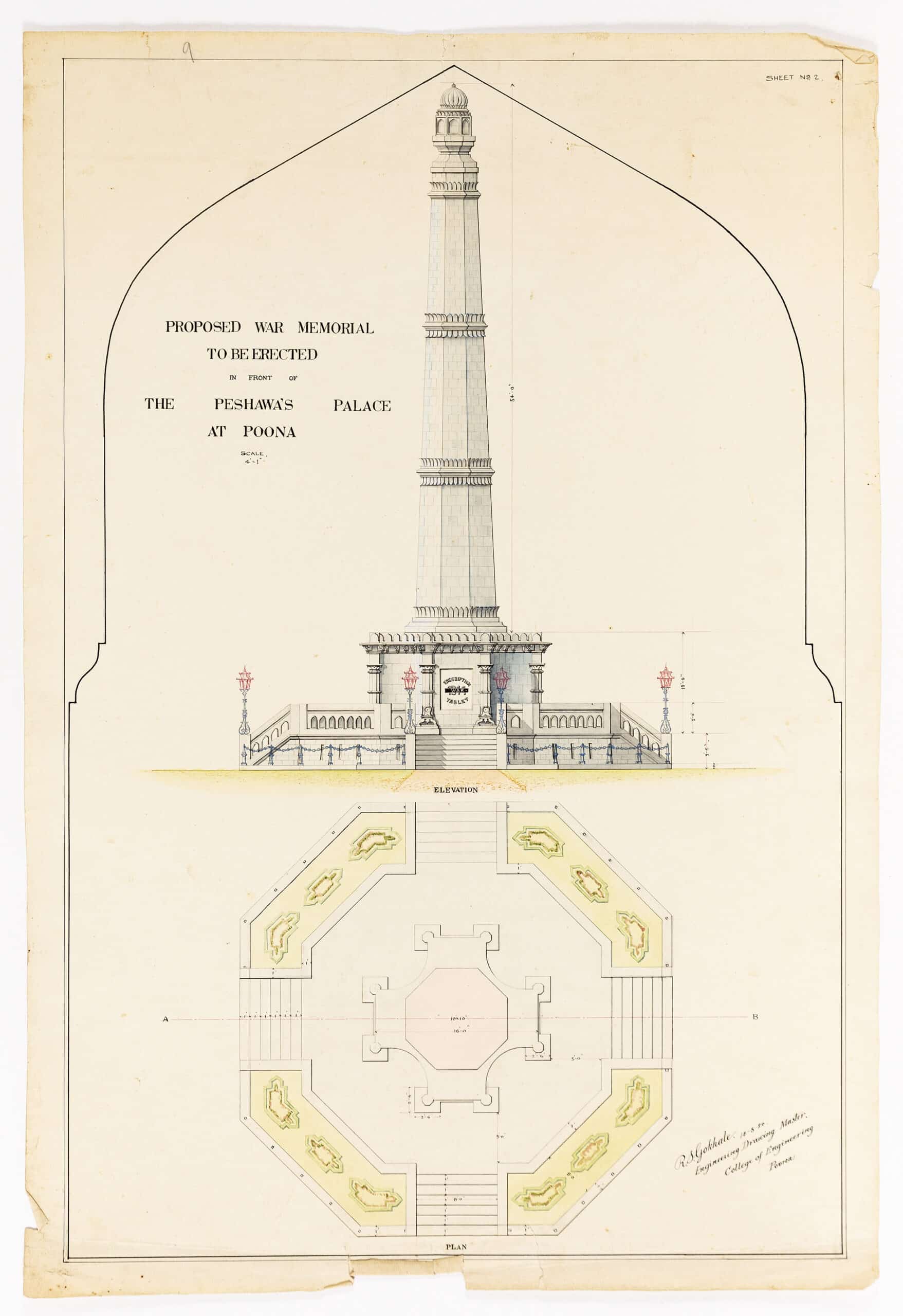

These three drawings, roughly contemporary to Gill’s, propose a war memorial outside the fortified walls of the Peshwa’s Palace (known today as the Shaniwar Wada) in Poona (Pune). The inscription on the sheet below suggests that the drawings are a student project for a masters in Engineering Drawing at the College of Engineering in Pune.

– Deanna Petherbridge