Behind the Lines 8

Annette Berthe Schlegel, wife of Adalbert, mother of Mariana, Friedrich, Werner and Elmira, and grandmother to little Wilhelm and Lydia, died peacefully in her cherry wood bed at home in Marienstrasse, Stuttgart, on March 29th, 1812. Adalbert, a successful watchmaker, had held Annette dear, and two weeks after the funeral called together his family to discuss her memorial. He felt it was appropriate that they should help him choose it — and in any case he felt unconfident; Annette had always decided matters of taste.

The carriages of the three married children drew up outside the house; unmarried Elmira, seeing them through the window of her mother’s room, where she had been trying to master the household accounts, ran downstairs to meet them. She led them up to Adalbert’s library, with shelves of books (many uncut — he was, truth to be told, fonder of double-entry book-keeping than books) set against green striped wallpaper — Annette’s final domestic decision. Dressed in mourning, they sat stiffly around the table and talked quietly among themselves. Lydia was sent to sit in a corner with Märchen der Brüder Grimm, and Wilhelm to play with his puppets.

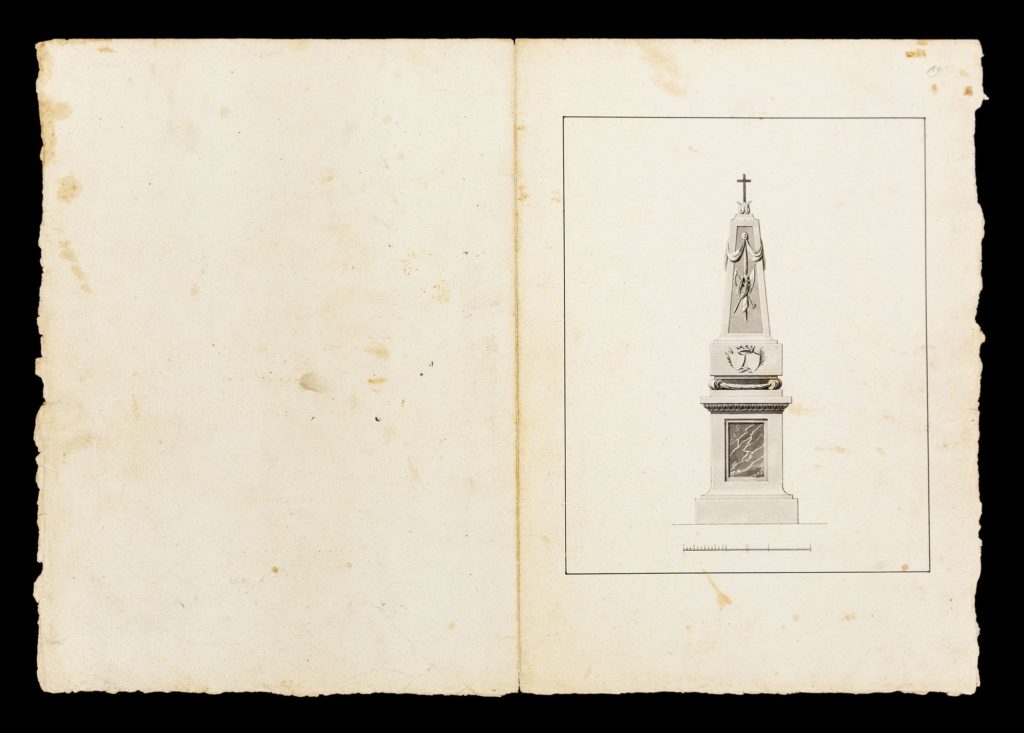

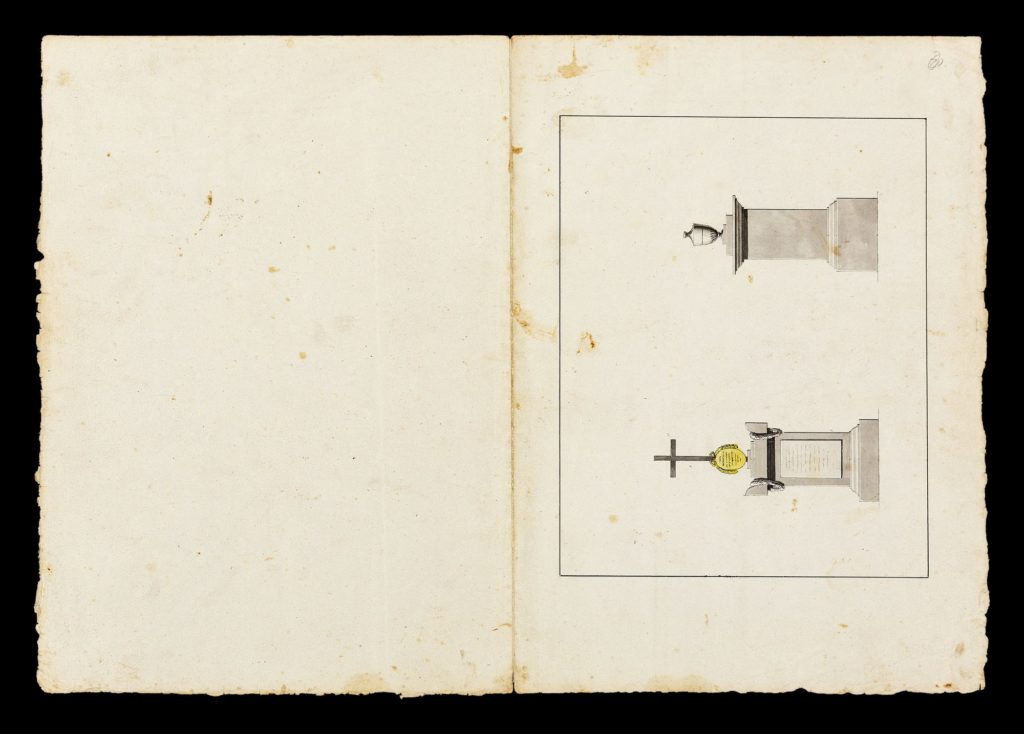

Adalbert coughed quietly and began: ‘I have here an album of the newest tombstone designs painted by Herr Moos for Meister, the stonemason. The Pastor has approved them. My favourite is number 14. [2453.7r] I think the obelisk is striking and will stand up above the others, but with the cross at the top, it is clearly Christian. We could put our initials on the entwined shields — leaving out the coronet, of course.’

Mariana peered closely at the drawing. She burst out: ‘Vater, I know you freemasons love obelisks, but I think there is something very masculine about them. Anyway, I really don’t think Mutter should lie underneath that gruesome Father Time scythe crossed with a flag. Surely flags are for the military and she would never have countenanced a victor’s laurel wreath.’

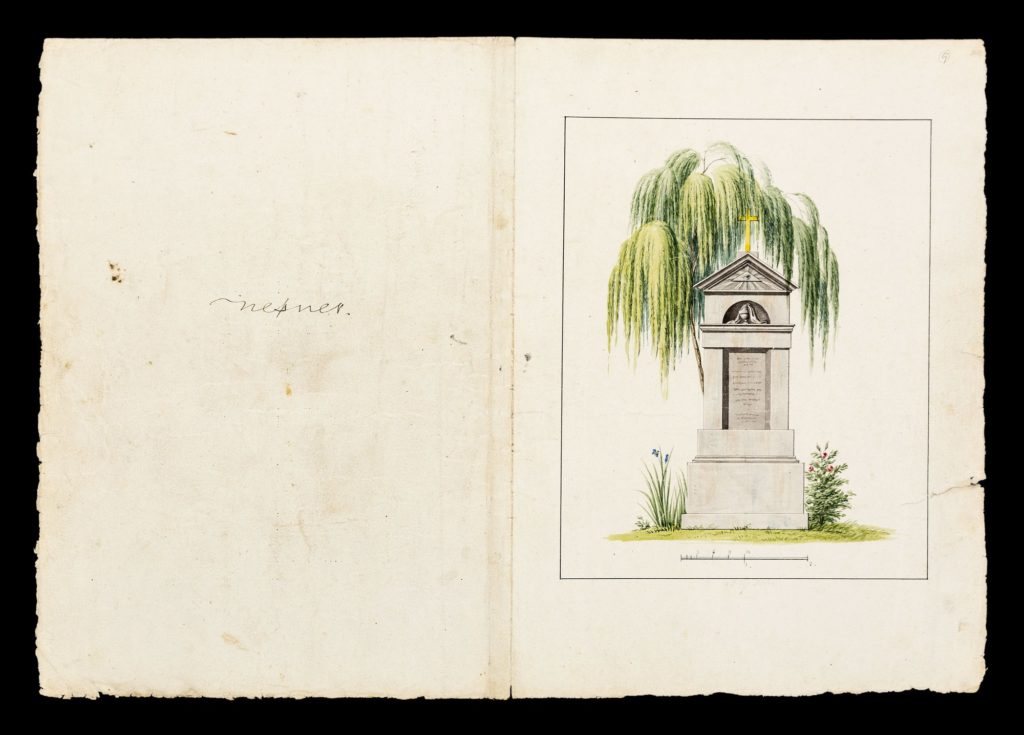

‘Well I do feel that your mother was cut down while still in her prime of life, but I see your point about the flag,’ her father replied and then continued: ‘I hope I will live to see young Wilhelm join the firm, but I should like to state now that I think number 9 [2453.5r] is a very fine design. Mariana, please make a note. I am proud to be a freemason and the eye of God ornament in the pediment, naturally together with a cross, will be eminently suitable for when I am finally called to Him.

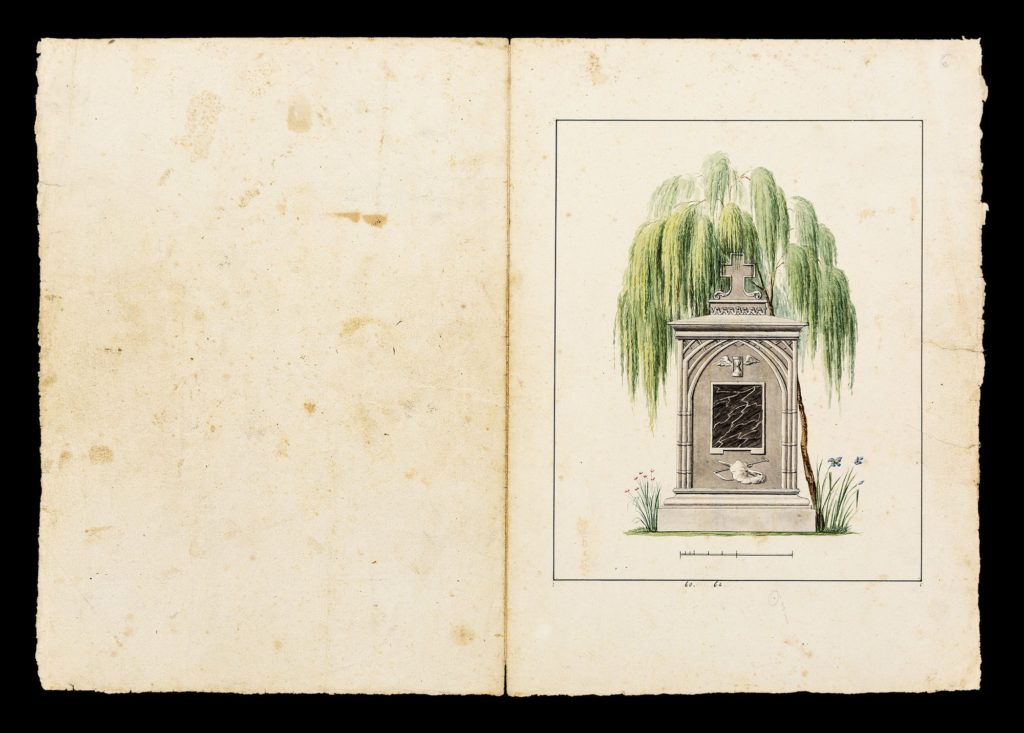

Mariana leafed through the drawings: ‘If you like the scythe, Vater, what about number 6? [2453.3r] The scythe is rather obscured from the smoke of the extinguished torch — a more delicate reference to life’s end. Perhaps we could ask Meister to leave out the hourglass with wings: one death ornament is quite sufficient for one tombstone. The Gothic arches are pretty, like a church. Shall we too plant a weeping willow — so appropriate to represent a grieving family, but I wonder why Herr Moos has also included iris and dianthus?’

Elmira’s bookishness and erudition were disapproved of by her father, who worried it put off potential suitors, but she decided to speak up: ‘ Mariana, they are absolutely correct: the Greek goddess Iris stood for a rainbow and acts as a link between heaven and earth — perfect for a grave. Then in Christian legend the dianthus grew from the Virgin Mary’s tears as she watched Jesus carry the cross, so it represents Motherly Love. How clever of Herr Moos, I should very much like to meet him.’

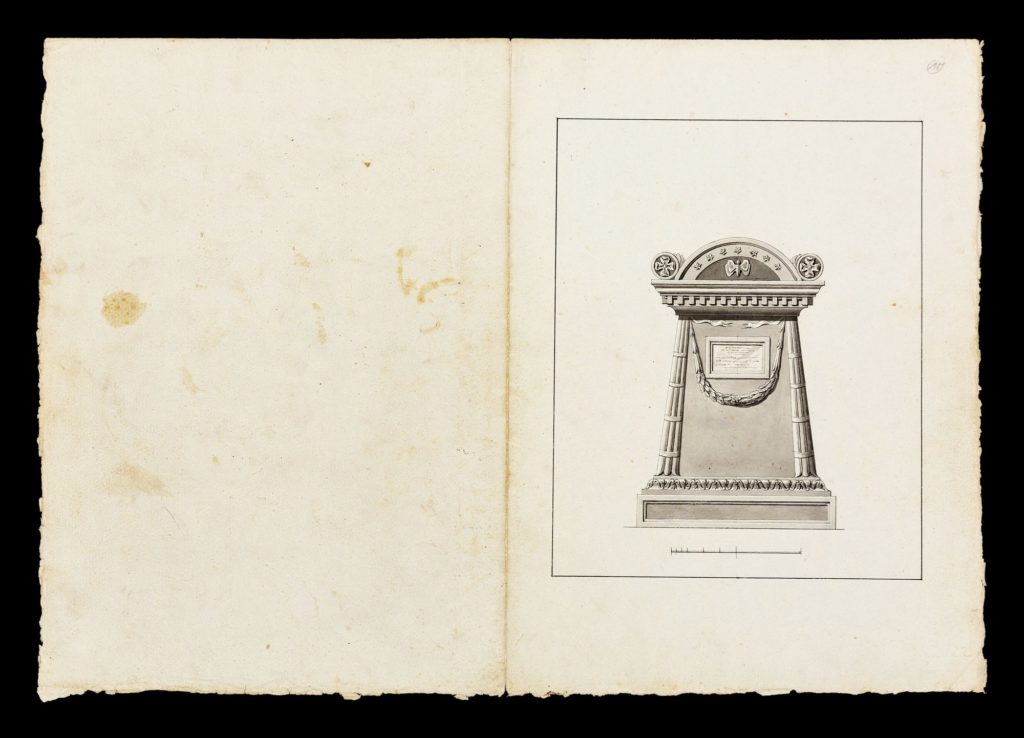

Friedrich, used to being under the collective thumbs of his sisters, but, wishing to impress his Father, whose business he would inherit, spotted a more cheerful ornament representing the fleeting quality of life: ‘Meine lieben Schwester, look at this: number 15 [2453.8v] has a charming butterfly on the tomb. Since there is no smoke from downturned torches one could disregard their meaning. I think the classical mouldings far superior — dignified and appropriate for Vater’s wife. He is, after all, a man of standing.’

Werner had been silent. His venture into publishing poetry was making him daily poorer, so the idea of expense made him inwardly shudder. His soft voice shook slightly: ‘I think of Mutter as shy and retiring. She would have disliked such show, why don’t we choose one of these plain ones at the back of the album? Here, the right hand one on sheet number 20 [2453.10r] — just a plinth with a lidded funerary urn. We could run to a piece of black veined marble for the inscription. Have we decided what words we will use? I would be delighted to write a short poem…’

‘Dummkopf, that is a terrible idea — well, perhaps not the poem, but design is impossible. People would think Vater a skinflint,’ Friedrich almost shouted. ‘Also, a cross is obviously essential, after all Mutter went to the Johanneskirche every Sunday.’

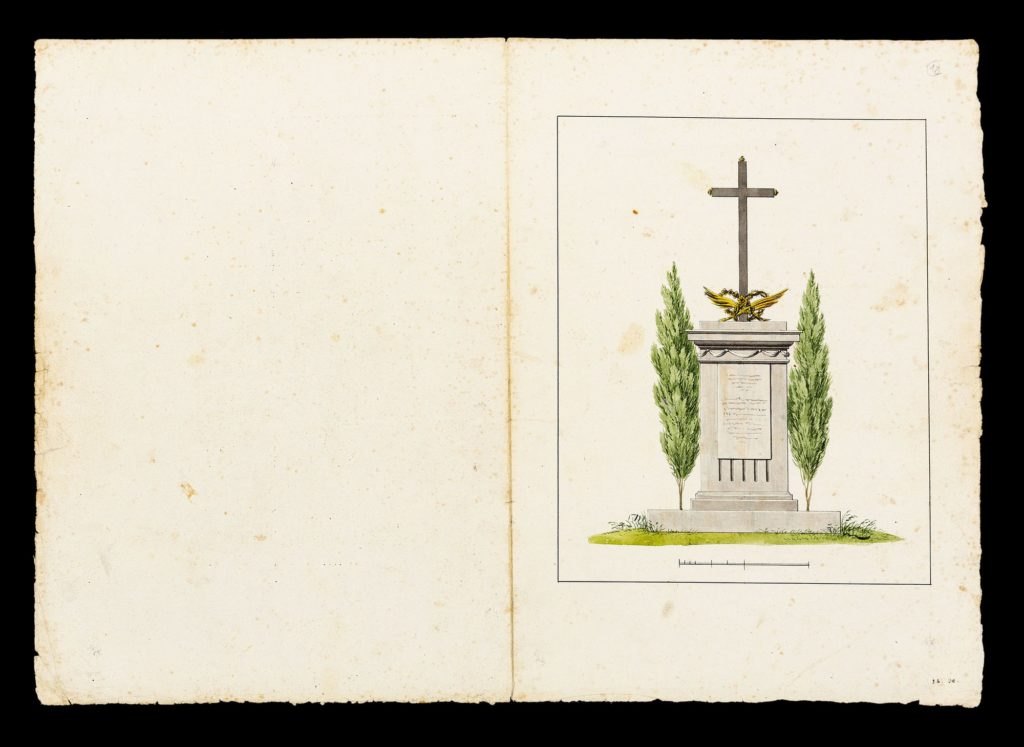

‘That means we should choose number 11 [2453.6r]. The cross is large and, as she happened to die on Easter Day, the crown of thorns peculiarly appropriate, and the Virgin’s crown of flowers pretty.’ Elmira was emphatic, and her humour, as ever, mildly subversive. ‘Besides, Mutter was a martyr to all our demands — particularly Vater’s — so the crossed martyrs’ palms would serve well as a remembrance of her character. However, on no account will we plant cypress trees: I have just read a most unpleasant story in Ovid about Apollo’s friend Cyparissus killing a tame stag and being so upset he wanted to weep for ever. Inevitably, it being a Greek myth, he became a cypress tree. Ridiculously gloomy.’

– John David Rhodes