Exploding Art and Architecture: Zaha Hadid’s Irish Prime Minister’s Residence Sketchbook

Zaha Hadid’s sketchbook for the Irish Prime Minister’s Residence (1979-1980), held at the Zaha Hadid Foundation with corresponding works at Drawing Matter, has proved invaluable for understanding her early career development of ideas. The project marked Hadid’s first professional solo endeavour, and she established her own office around the same time. The sketchbook dates from summer 1979 and gives a unique insight into how she refined her style, particularly through abstraction and the relationship between art and architecture, as part of her design process and presentation strategies. Hadid built on what she learned from Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) whilst making architecture that was more distinctly her own.

Hadid first encountered OMA at the Architectural Association (AA), where she studied on Diploma Unit 9, led by Elia Zenghelis and Rem Koolhaas, from 1975 to 1977. We must look to Hadid’s prize-winning Diploma Projects Malevich’s Tektonik (1976-1977) and Museum of the Nineteenth Century (1977-1978), as well as her time spent working with the practice to understand her Irish Prime Minister’s Residence more fully. Unit 9’s teaching revisited interwar modernist art and architecture in a bid to solve contemporary problems. Hadid responded outlandishly to her teachers’ brief to assign a site and function to a section of Kazimir Malevich’s Alpha ‘Arkhitekton’ (1923), an abstract sculpture that served as an incomplete architectural proposition. Rather than participate in the stipulated surrealist ‘exquisite corpse’ technique, where students’ separate designs would eventually come together, she turned its entirety into an hotel, pool and nightclub shipwrecked across the River Thames at Hungerford Bridge.

While Malevich prompted Hadid’s experiments with form and abstraction, it was her discovery of Ivan Leonidov at the AA that helped her to move from suprematist composition to Constructivist architecture, giving the former a programme. Museum of the Nineteenth Century adapts his strip designs into two intersecting beams that evoke a train crash at Charing Cross Station, the one directly above it housing a museum, crossed diagonally by an hotel. Hadid transposed Leonidov’s highly experimental cultural buildings and workers’ clubs that typified the Soviet ‘social condenser’ into late 1970s London and its Victorian infrastructure. Her use of colour was inspired by Suprematism initially, with the first painting for Malevich’s Tektonik created in solid blue, red, white, black and greys. This changed during the year or so Hadid spent as a partner of OMA following her studies. Her paintings for Museum of the Nineteenth Century, which appear to have been completed after her Diploma submission, show the influence of the practice readily in their intricate detailing and wider-ranging pastel colours. They were created at Koolhaas and Madelon Vriesendorp’s home, probably with her help and that of Zoe Zenghelis, and included in OMA’s 1978 exhibition The Sparkling Metropolis at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Working on their Dutch Parliament Extension (1978-1979) competition entry around the same time allowed Hadid to develop upon her student work for a project that responded to existing historic buildings and a tighter brief. In The Ambulatory and its Connections (1978), she devised a walkway between spaces for varied parliamentary activities. These were designed separately by Koolhaas and Zenghelis, further utilising the ‘exquisite corpse’ method. Hadid’s drawing featured a more dynamic axonometric view compared with two of her museum paintings. Structural components are highly fragmented, energetically expanding out towards the edge of the picture plane, evoking circulation and separation, and Leonidov’s strips.

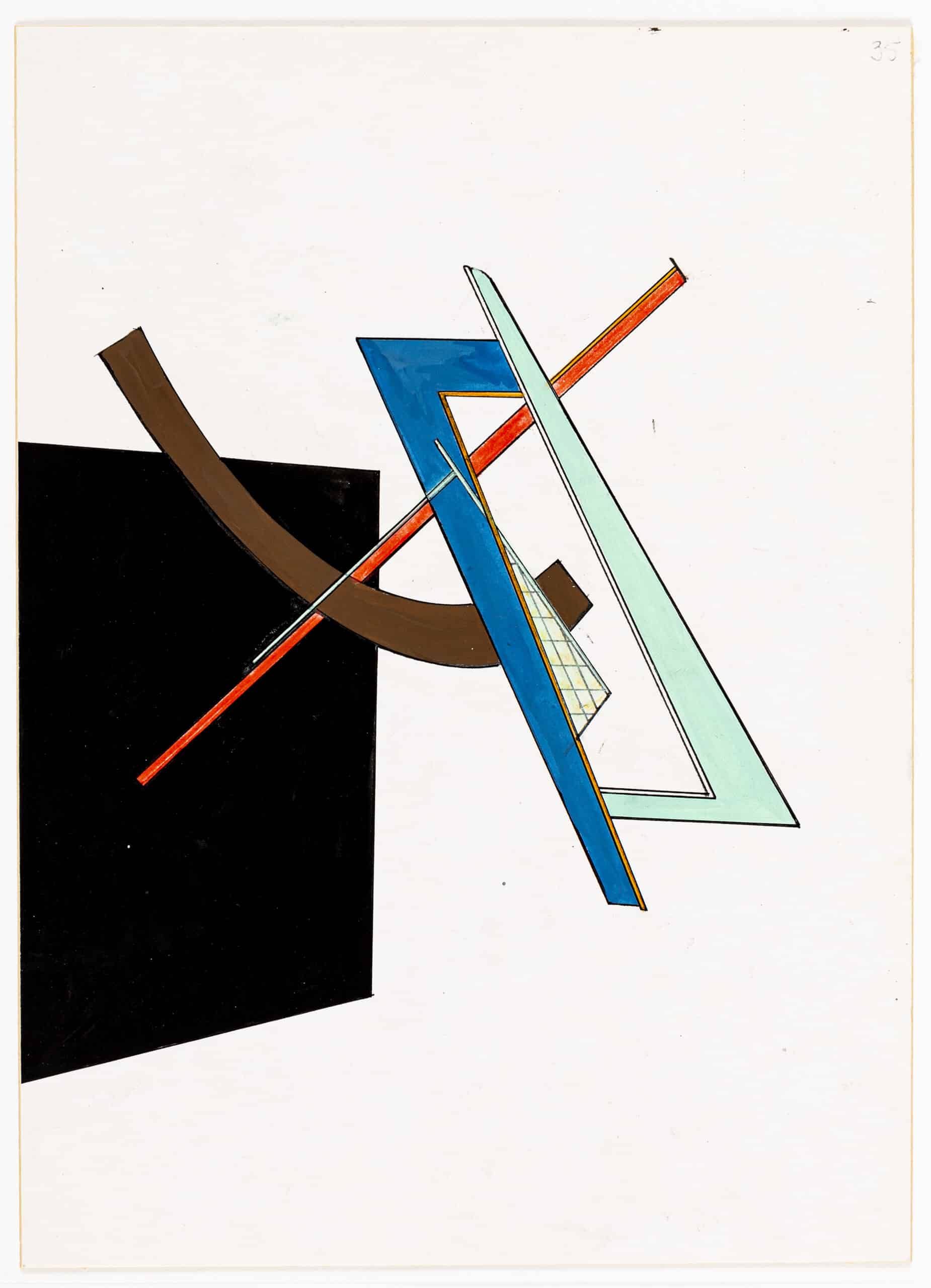

Numerous variants of The Ambulatory and its Connections have recently been uncovered within the Zaha Hadid Foundation (ZHF) Collection, including a black and white ink on mylar drawing mounted on linen, and a large hand-coloured print. Their size and format convey an intention for display. Desley Luscombe has noted that the painted print in the Drawing Matter Collection served as a colour experiment, and that others of the ambulatory were included in the exhibition Zaha Hadid: Planetary Architecture (1981-1982) at the Van Rooy Gallery in Amsterdam. [1] A hand-drawn and coloured version was found with different ambulatory drawings at ZHF, suggesting that Hadid used colour for the project while working with OMA. These newly discovered works show how it was explored in tandem with line, form and composition to highlight specific elements, conveying an adventurous programme that pushed the design parameters for a distinct political space for the Dutch parliament, as well as for exhibition purposes. Combined with the exploded axonometric format, colour aided Hadid’s attempts to fulfil Malevich’s aim to ‘liberate the plan’, to add a level of movement that allowed it to gain freedom from the ninety-degree angles of both the grid plane and the paper. [2] Given both contexts, the different versions of the ambulatory can be simultaneously read as semi-abstract artworks and drawings that show key project concepts. They oscillate between art and architecture, as well as two and three dimensions.

Such experiments were taken to extremes in Hadid’s sketchbook for the Irish Prime Minister’s Residence. She responded to a competition brief for a state guest house and a residence for the Taoiseach in Phoenix Park, Dublin. OMA also came up with their own design, and it was set as a project on Unit 9 when Hadid taught alongside Koolhaas and Zenghelis. She built upon her earlier club and hotel ‘social condenser’ schemes to create distinct public spaces for leisure and entertainment, and private accommodation. In its final iteration, a slightly off-kilter rectangle serves as the state guest house, confined to an existing walled garden, with lodgings and public facilities including a pool within its perimeter. Its boundaries are disrupted by a triangular entrance reception block with a library above, and a floating suite that cuts diagonally across the rectangle to the garden. Two intersecting irregular beams are the prime minister’s residence, split into a private suite and reception rooms, which sit close to an existing medieval tower.

Hadid said of the project that ‘In the end, every object had a different form or shape, although it wasn’t really conceived that way’, [3] and that ‘The early sketches are very important – it was a composite of these that produced the plan’. [4] Uniting form and programme, the project is worked out through abstract shapes that correlate with the separation of public and private space, guests and the Taoiseach. We get a far greater sense of the project’s ‘liberation from the plan’, as its components ‘exploded’ out into fragments throughout the surrounding landscape, or ‘imploded’ upon themselves. [5] As Hadid explained, ‘I wanted to push the notion of explosion in architecture and that’s what this project really taught me – pushing something to a certain limit where it doesn’t become ridiculous, where you are very much in control, and it erupts only where it is possible’. [6] This was in stark contrast to OMA’s interpretation of the brief: comparing the two, Elia Zenghelis remarked ‘While ours espouses and adapts itself to the contours and curvilinear pathways of Phoenix Park, Zaha’s is an explosion on impact, and a virtuoso reassembly of architectural shrapnel’. [7]

Hadid’s sketchbook doesn’t offer a chronological or progressive reading of the project’s development from beginning to end, which is in keeping with its irrational logic. Pages might have been reworked or blanks filled in later, and some numbering and dating potentially added. For example, it begins with a sketch from Tuesday 25th July 1979 which appears close to the final forms of the project in plan, and finished with colour, but it reads as abstract and two-dimensional. Only on the next page does a far simpler sketch suggest that its elements could become three-dimensional. The fourth page lists ‘Mies Melnikov Malevich’ as inspiration alongside a rougher series of pencil sketches. They seem earlier, exploring various compositions of overlapping triangles, curved lines, crosses, beams and warped rectangles, echoing Malevich’s suprematist compositions. Hadid discussed in an interview about her project how she admired Mies van der Rohe’s bent plan for Court-House with Garage (1934), which prevented stasis, instead ‘energizing the ground condition’. [8]

Unlike Malevich and Leonidov, Konstantin Melnikov showed how the ‘liberation from the plan’ could be finally achieved in completed buildings. The most likely source for Hadid was his 1925 Soviet Pavilion, given its triangles and obliques that defiantly countered the right angle. The triangle was a new form for Hadid’s architecture and key to the explosive dynamics of the Irish Prime Minister’s Residence, for ‘if that triangle then hits a wall, certain things erupt, due to a sheer physical power… it’s only in these moments that things begin to burst’. [9] The combination of the artist and two architects, then, helped her to eventually work out how to transpose her abstract sketches into architecture, responding to the ground conditions and the constraints of the site by bending and exploding her plan. Across the following sequence of pages, the geometric elements of the project swoop and crash into each other, expanding and contracting within the parameters of the page, and are viewed from multiple angles. Coloured pencil emphasises different parts of the project, such as divided blue triangles with green, red and orange accents hurtling into brown and pink brick walls.

Further into the sketchbook is a series of what Hadid called ‘cut-outs’, which explored the process of ‘elimination’, creating a ‘composite’ of sketches with painted and drawn elements that informed the final plan. [10] Pages are deliberately torn or cut, allowing aspects of the next to be visible. One even incorporates painted wooden sticks, adding a three-dimensional element that breaks through its flat surface. These techniques accentuate the dynamism of Hadid’s design and the importance of fragmentation and abstraction. They also nod to the concealment and revelation of the ‘exquisite corpse’, and its proximity to collage. As the sketchbook pages turn, the project is stripped back to the blue triangle cutting into an irregular black rectangle outlined in red, which seems to have inspired the catalogue design for the Van Rooy exhibition. [11] The black rectangle then finally stands alone, akin to Malevich’s Black Square painting (1915). We also see the evolution of the Taoiseach’s residence from shattered pieces into intersecting beams that work in equilibrium with the plan’s circulation, and the collision of shapes that combine to make the state guesthouse. Grid lines within elements of the project along with bold and pastel colours emphasise its liberation, from the confines of the site and the sketchbook page.

The proximity of the Irish Prime Minister’s Residence to art proved to be important for the project’s afterlife and display, and further drawings and paintings for it were shown at Planetary Architecture (1980). The Drawing Matter Collection holds works that match pages of Hadid’s sketchbook exactly in composition, down to the page numbering and positioning of text, which suggests they were photocopied then hand-coloured. The provenance of one points back to Van Rooy, so they may have been made around the time of the exhibition. At ZHF, we have found numerous similar coloured copies, some signed by Hadid like individual artworks. Reworking her sketches and removing them from the context of the project sketchbook turns them back into abstract art. This effectively reverses the process Hadid learned while studying on Unit 9 with Koolhaas and Zenghelis and made manifest in her celebrated diploma submissions, like turning her Tektonik back into a sculpture full of architectural promise. However, it continued in the same vein as OMA’s interest in producing artworks for exhibition and publication, and their relationship with commercial galleries such as Van Rooy. The exploration of thresholds, then, both in the Irish Prime Minister’s Residence and those of art and architecture, was central to Hadid’s early designs, across their development, circulation and display. In her own words, ‘I began to develop my own language, I began to take a different direction, something which was quite personal’, it became something of a signature.[12] Through abstraction, she exploded the nature of what architecture could be.

Notes

- Desley Luscombe, Zaha Hadid, Online Article, Drawing Matter, 27 November 2018, <https://drawingmatter.org/zaha-hadid/> [accessed 29 January 2025].

- Zaha Hadid, ‘The Calligraphy of the Plan’, in Architectural Associations: The Idea of the City, ed. by Robin Middleton (London: Architectural Association and Alvin Boyarsky Memorial Trust, 1996), 65.

- Alvin Boyarsky, ‘Post-Peak Conversations with Zaha Hadid 1983 & 1986’, in GA Architect 5 (Tokyo: A.D.A Edita,1990), 12-13.

- Hadid, ‘The Calligraphy of the Plan’, 66.

- Ibid, 66.

- Boyarsky, ‘Post-Peak Conversations’, 13.

- Richard Hall, OMA Conversations, 2. Elia Zenghelis – Watersheds, Conversation 005, Oral history Interview, Drawing Matter, 18 February 2022, <https://drawingmatter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/DM_RH_EZ004-6_C24.pdf>, [accessed 29 January 2025].

- Hadid, ‘The Calligraphy of the Plan’, 65.

- Boyarsky, ‘Post-Peak Conversations’, 13.

- Hadid, ‘The Calligraphy of the Plan’, 66.

- See Zaha M. Hadid, ‘Planetary Architecture, Projects 77-81’, Pamphlet Architecture, 8, 1981 and Zaha M. Hadid, Exhibition Catalogue, Projects 1977-81, 1981.

- Boyarsky, ‘Post-Peak Conversations’, 13.

Dr Catherine Howe is Research Officer at the Zaha Hadid Foundation and specialises in twentieth-century European and American art, architecture and design, particularly interdisciplinary exchange. She received a postdoctoral fellowship from the Paul Mellon Centre in 2021 and has previously worked for Tate, Centre Pompidou, the Royal Academy and Barbican, including the exhibitions Queer British Art, Noguchi and Postwar Modern. She has also taught at the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of Sussex and the Open University.