Fabric Fabrications

Interpretation

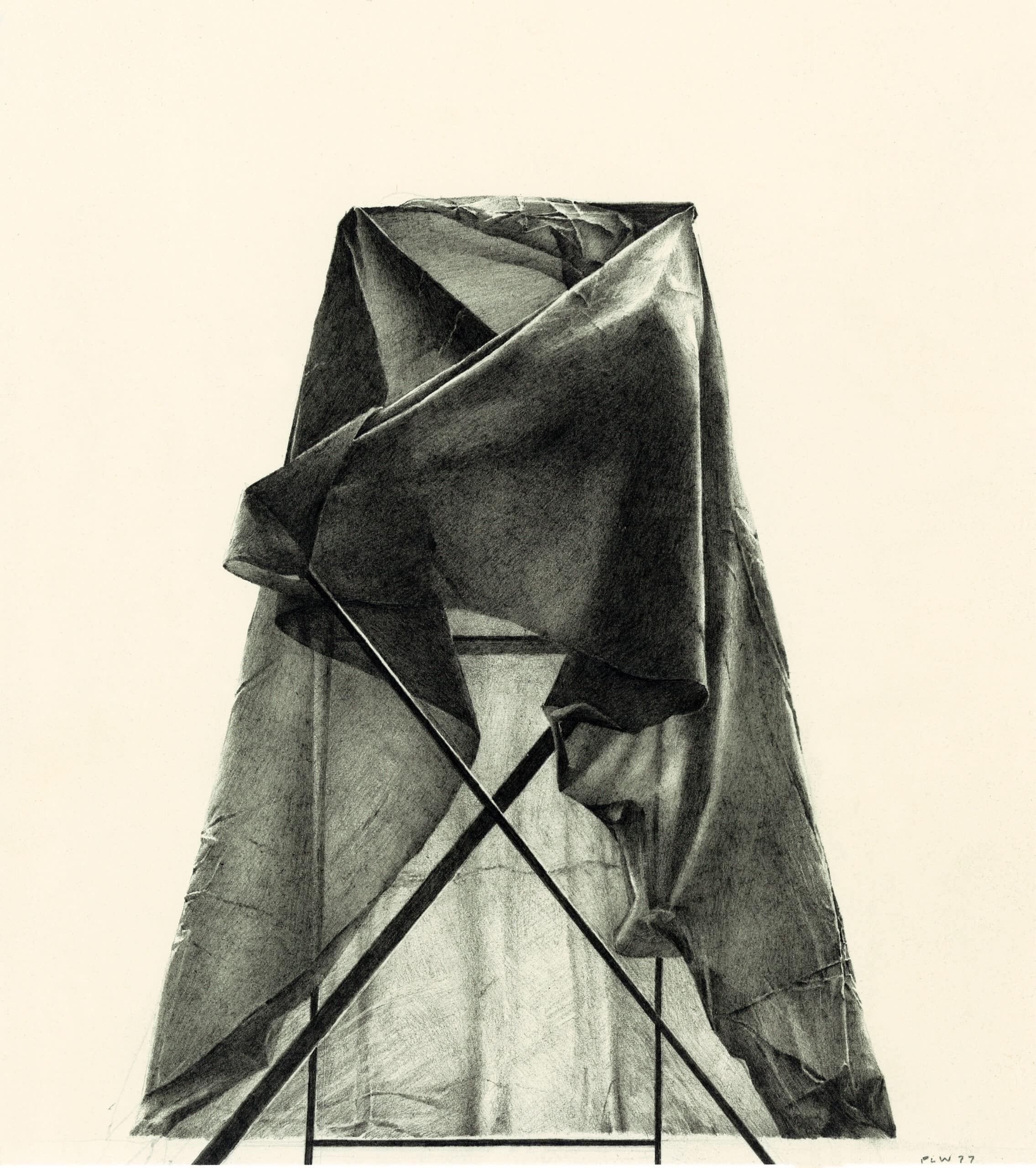

I am very grateful to Mark Dorrian for his reading of my 1977 drawing. [1] While at the time of its laborious production, the word shroud was not uppermost as my intended coding, I can now see that the dark, drawn folds have a real, symbolic or imaginary resonance—subsequently triggering Walter Benjamin’s hypothesis that a work of art is only complete once the critic has interpreted it.

But in taking on board the shroud reading, we fall into a codified historiography of shades like Poussin’s body of Phocion (swathed in white cloth) being carried out of Athens, or the two enshrouded souls being ferried to a fiery Hades by a naked (and very much alive) Charon painted between 1735 and 1744 by Pierre Subleyras.

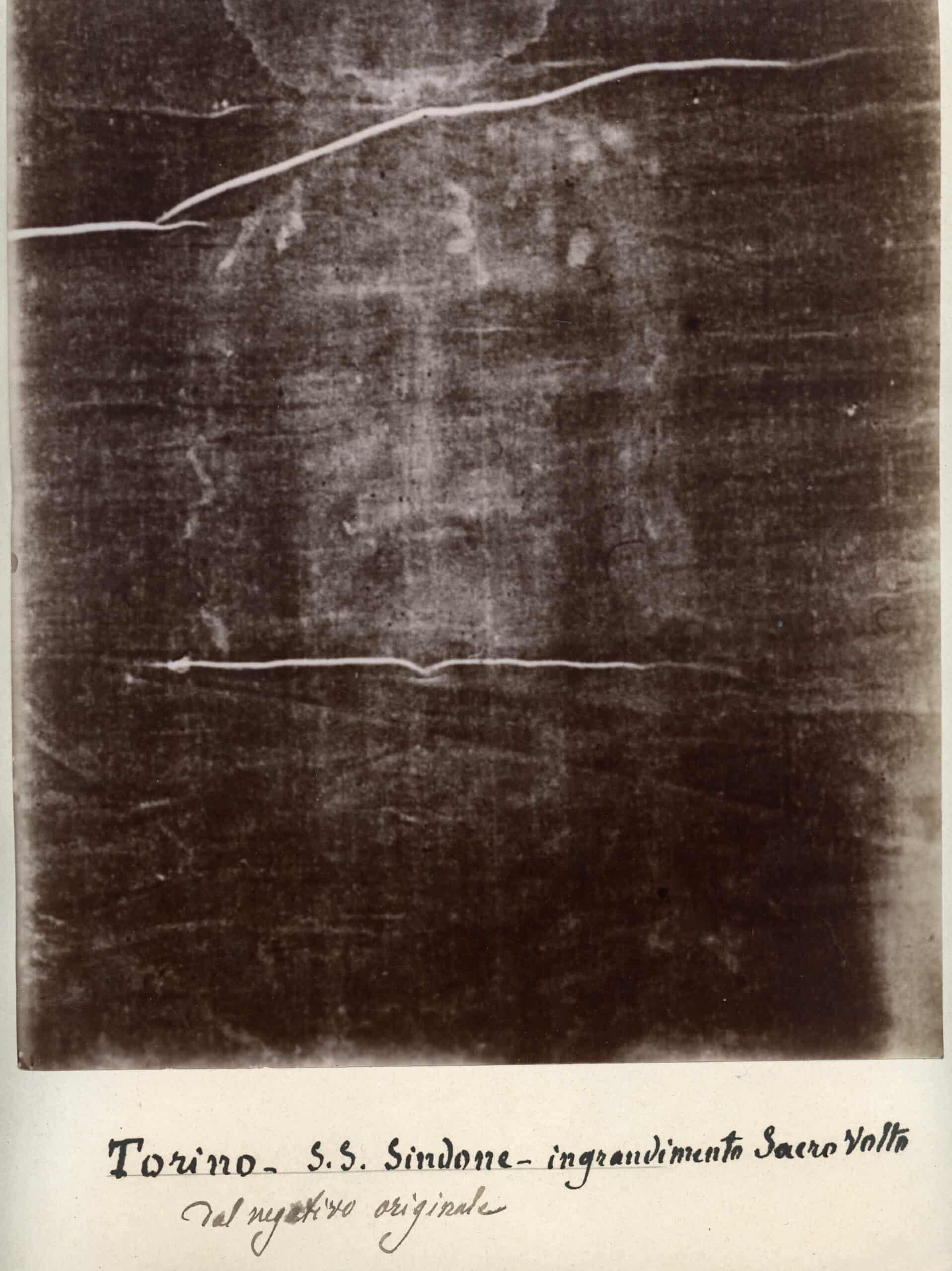

It was not my intention to be aligned with the Turin Shroud, that Vera Icon re-substantiated in 1898 by Secondo Pia and the then new medium of photography. Skiagraphy was my subject, shadows to be read intuitively and deductively, not yet quantified by Lambert’s Law where, ‘the quantity of light reflected from any unit area of the surface towards the viewer is directly proportional to the cosign of the angle between the direction of the viewer and the normal or perpendicular to a perfect diffusing surface,’ as quoted in Michael Baxandall’s Shadows and Enlightenment (1995).

Evolution I

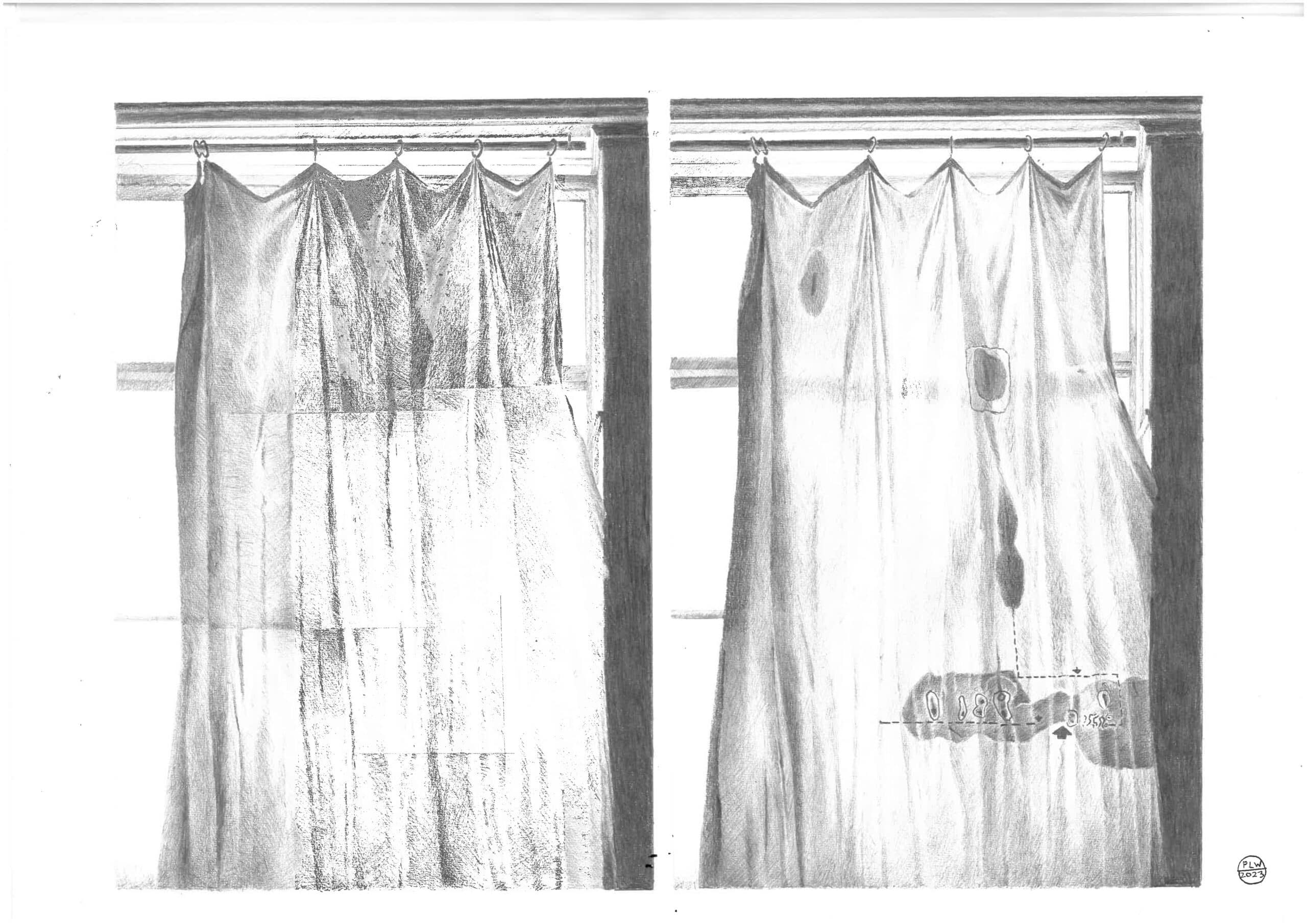

The evolution of this enigmatic drawing was, in fact, extremely pragmatic and demands a factual history. The drawn cloth is backlit, which implies a large window—the north-facing window of the nineteenth-century artist’s studio I had just moved into. To screen the window, a large piece of rough white cloth was draped over a rectangular frame of wooden struts, with two crossed lateral bracings (rudimentary tectonics).

Creases from folding added a vein-like topography to the draped fabric. Noticing this, I set up my drawing table frontally addressing the accidental tableau, and spent a few weeks carefully inscribing the shadows onto a sheet of white cartridge paper. This was 1977, I was an AA teaching assistant with time on my hands and a head full of Boullée and Ledoux from seminars with Tony Vidler. (Boullée claimed an architecture of shadows as his invention.)

Reception

The drawing was first presented at an informal discussion group called ‘The Architecture Club’. This consisted mostly of us, young turks of the AA (Nigel Coates, Jenny Lowe, John Andrews, Rodney Place, Trish Pringle, Fred Scott and Robin Evans), and was set up by Paul Shepherd and Will Alsop, both co-opting their respective mentors (James Gowan and Cedric Price) as senior club members. Cedric got quite excited when the ‘Shroud Drawing’ was presented, perhaps because of its impermanence, its contingency; he was not an enthusiast of graphic indulgence, at least not on juries of my subsequent AA Diploma Unit.

Utility

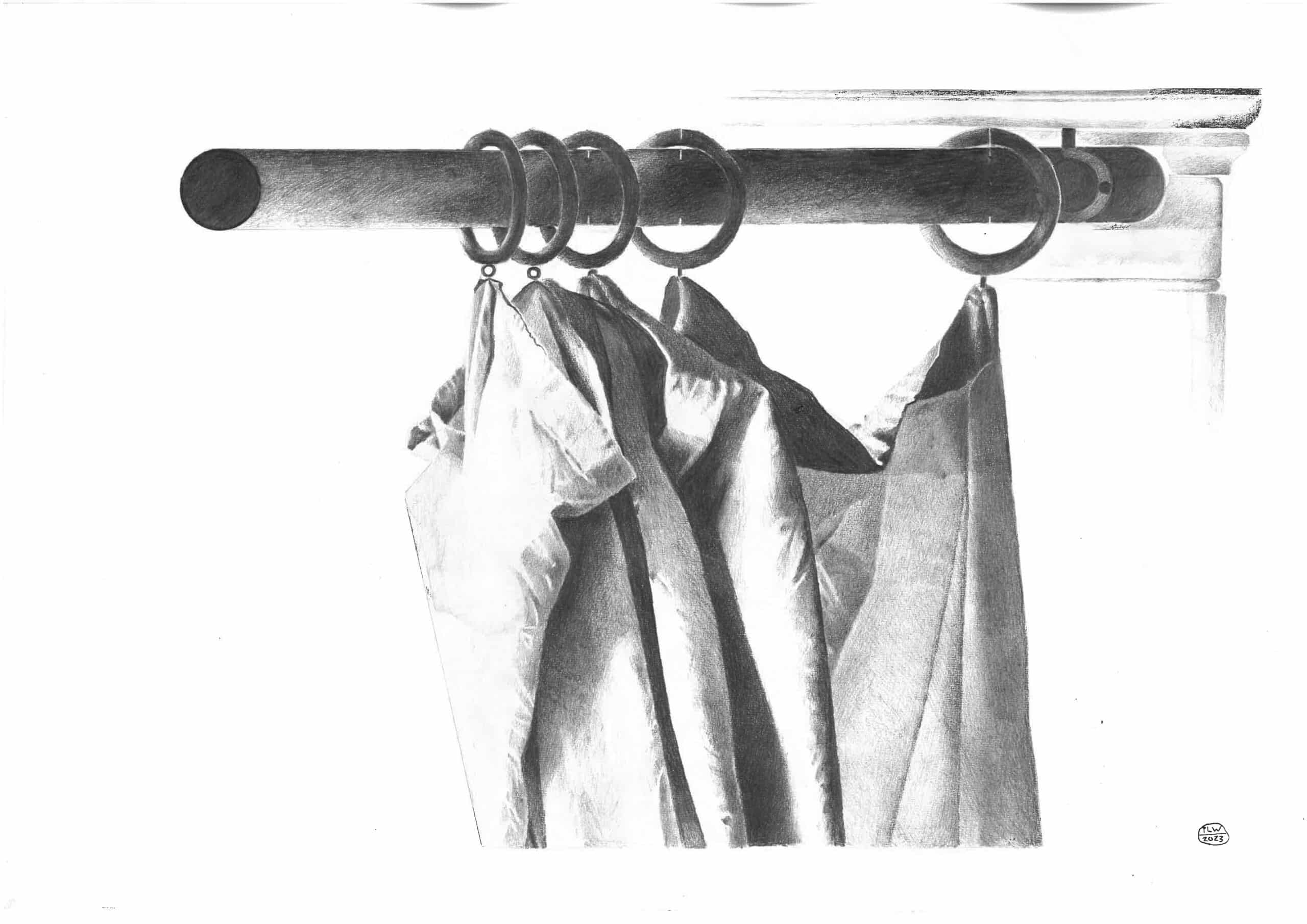

Roland Barthes once wrote that the civilised future of a function is its aesthetic ennoblement. An evolution that this piece of white cloth played out in reverse. It emerged in a highly aestheticised format and then fell, as a curtain, into the regime of utility. For this, a chunky round wooden rail was installed, and the now sewn cloth was suspended on circular rings. Aren’t all rings circular? Yes, but seen in the oblique, they are elliptical. This hanging, along with the monk-like folds of the suspended fabric, was the subject of the second pencil drawing of this sequential graphic discourse.

Evolution II

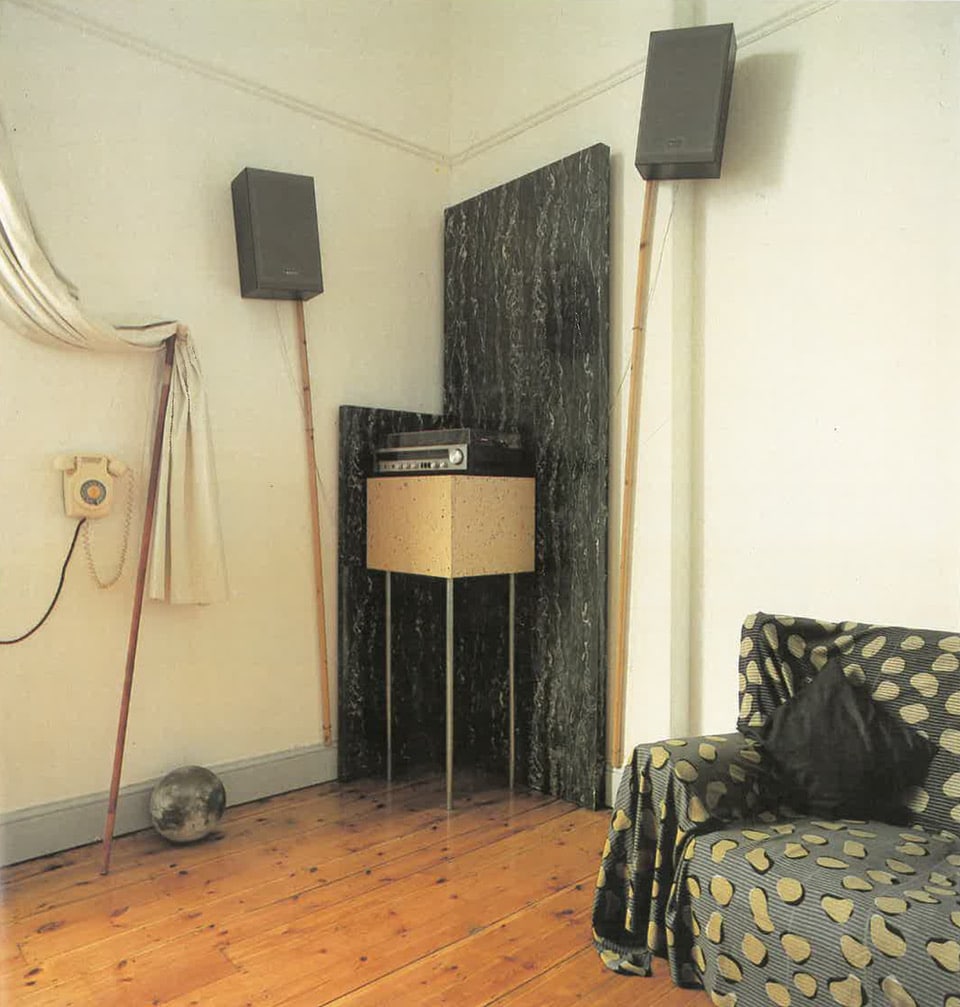

There was a 46-year gap between the Shroud and the Second Curtain Drawing. I was 27 when I drew the first and 73 for the second. The studio became the home base for the Bolles-Wilson family and then the London base, once BOLLES+WILSON had relocated to Germany. The fate of the abandoned curtain was not entirely fortuitous, although it had at one moment achieved a public profile as a style prop.

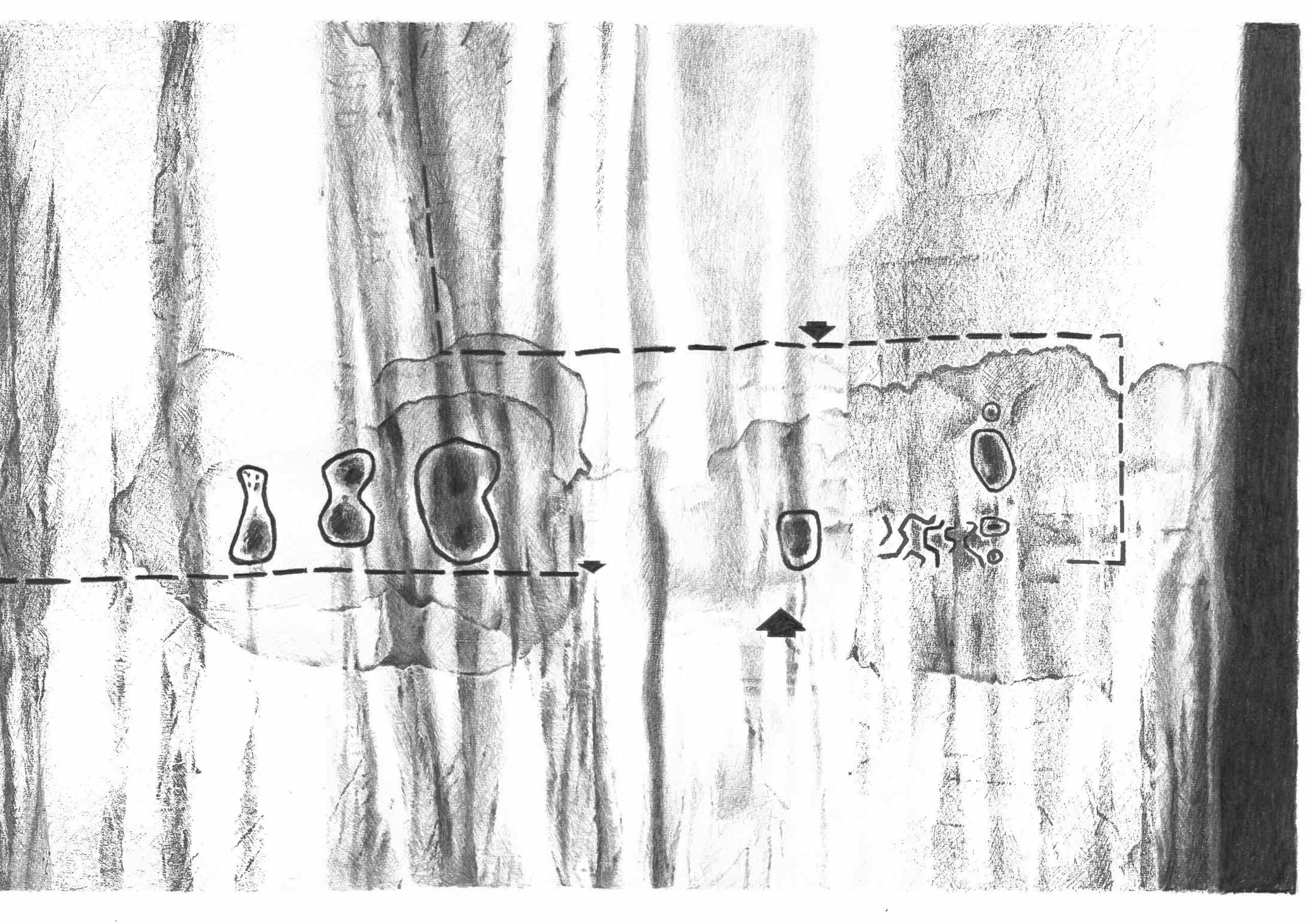

But on one return, it was found brutally stained—a water leak from the above studio. This violation of the virginal white is also documented in graphite, as well as my further pimping of the accidental markings with a felt-tip graphic. Here, the curtain graduates to the surface of inscription.

In the final drawing of the sequence, the over-drawing of the stain was again redrawn in graphite. To my great relief, my aged eyes and hand were still up to the level of graphic verisimilitude propagated in my youth.

An Ancient Art

The ancient Greeks Parrhasius and Zeuxis competed to be the best painters in Athens. Zeuxis painted grapes so real that birds flew down to pick at them. He then asked Parrhasius to draw aside a curtain to show what he had painted on the wall behind. Parrhasius won; the curtain was the painting.

The wrinkling of fabric over a corporal form was, of course, mastered by ancient Greek sculptors as seen on the British Museum’s controversial Elgin Marbles. At the time of their theft, Lord Byron in Athens with John Cam Hobhouse had written ‘Lord Elgin – the greatest patron of larceny Athens ever saw.’ This quote is inscribed across my recent Villa Elgin drawing, which moves on from curtains to drapery. Walter W. Skeat’s Etymological Dictionary of the English Languageallies the word shroud to shred, a piece of cloth.

BOLLES+WILSON

To conclude, two more inscribed curtains, both from the oeuvre of BOLLES+WILSON. The first, a gold star emblazoned on a blue curtain for the Children’s Library of the 1993 Münster City Library, which was inspired by a super poetic Fairy Tale corner in Asplund’s Stockholm Library. We projected a small stage for a clown to spring out on, or for Fairy Stories to be read to school classes—the original furniture, now long since worn out, was upholstered in Mice and Dice. Recently, this space was the venue for a Lego Saturday.

BOLLES+WILSON, The curtain at the Children’s Library of the 1993 Münster City Library during a Lego Saturday, depicting the curtain after 30 years of use.

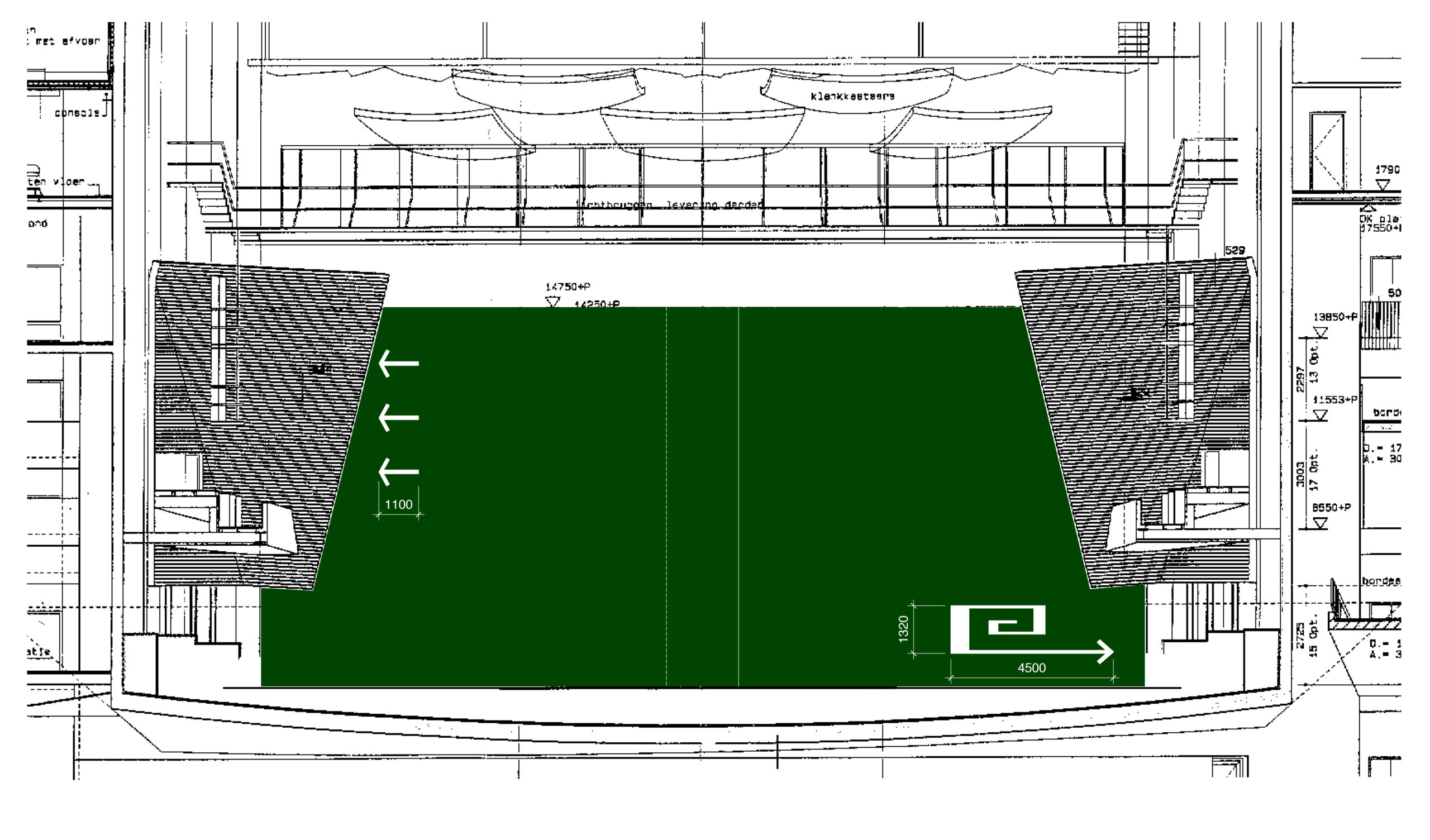

For our 2001 Luxor Theatre in Rotterdam, the Green Stage Curtain also received a graphic inscription—three arrows indicate a chorus exiting stage right, while a spiral (a pictogram of the building’s plan) signals ‘star to exit stage left’.

Notes

- Mark Dorrian offered his reading of the Shroud at the Drawing Conversations roundtable discussion that took place at The Cooper Union in February 2023, see here: https://cooper.edu/events-and-exhibitions/events/roundtable-discussion-drawing-conversations [accessed 18 August 2025] and here: https://vimeo.com/800907233?fl=pl&fe=sh [23:08].

*

Peter Wilson is a founding partner in Architekturebüro BOLLES+WILSON. Peter is the author of Some Reasons for Traveling to Italy (2016), Some Reasons for Traveling to Albania (2019) and Bedtime Stories for Architects (2023). His drawings are held in the collections of Drawing Matter, V+A, CCA, and DAM Frankfurt. BOLLES+WILSON are the subject of three El Croquis Monographs and the publication, A Handful of Productive Paradigms (2009)