The Garden of Earthly Delights

Despite the great success of the architecture sector in the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, the newly created garden and landscape section curated by Jean-Claude Nicolas Forestier received unexpected attention. Forestier commissioned pairs of artists and architects to design ‘instant’ gardens to flank the pavilions: instant because they had to bloom immediately and last for the duration of the fair, from April to October. Robert Mallet-Stevens came up with an ingenious, though not universally admired, solution to this difficult problem: together with the sculptors Jan and Joël Martel, he made a garden where the trees were cast in concrete.

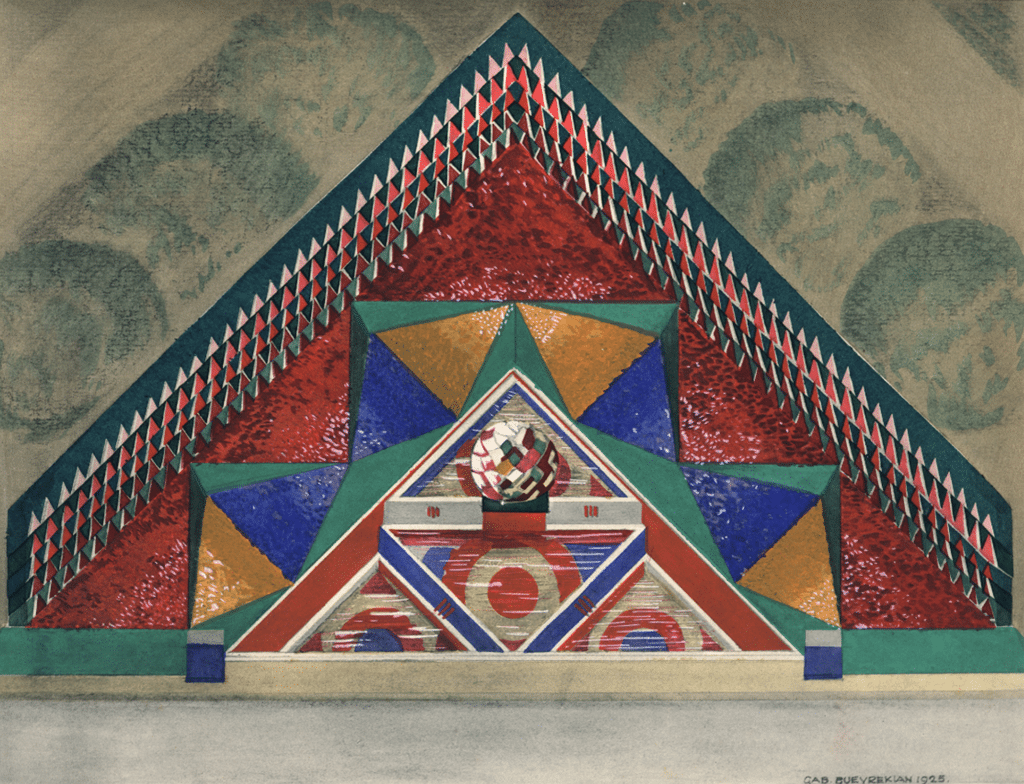

Alongside this French-modernist take, Forestier themed other installations according to more conventional geographic divisions: Arabic, Moorish, Spanish, Italian, Japanese, and so forth. [1] He appointed Gabriel Guevrekian designer of the Persian garden. The Armenian-born Guevrekian had grown up in Tehran before moving to Vienna to study architecture under Oskar Strnad, Josef Frank and Josef Hoffman. Now, just 25 years old and in Paris, he had to fit his design into an oddly shaped plot, an elevated corner site that opened onto the main exhibition pathway, just in front of esplanade des Invalides. Titled Jardin d’Eau et de Lumière (Garden of Water and Light), his installation was the precise realisation of a conceptual painting of the scheme he had produced earlier in the year – an abstract illustration of a flattened axonometric view. With its vivid shades of crimson, green, yellow, and cobalt blue forming an abstract yet playful composition of triangles, the painting borrowed both from traditional Persian miniature composition and from the style of Guevrekian’s Cubist friends, in particular from the artist Robert Delaunay’s Windows or Circular Forms series.

As built, the garden was simply a stylised triangular walled space, a piece of landscape contained within a boundary made of concrete and colored glass and designed to be perceived only from the outside. At its centre was a tiered fountain, on top of which Guevrekian installed a revolving sculpture by the French glass artist Louis Barillet – ‘rather a nightclub trick than a serious attempt at garden decoration’, sniped the critic Fletcher Steele. [2] The space between the fountain and the walls was geometrically patterned, with triangular patches of flowers and grass forming solid colors of orange, purple, red, and green, and each panel was also slightly tilted to follow the inclined ground plane. The striking effect of these colors and the geometric composition as a whole meant that the garden immediately became one of the most noticed and debated installations in the exhibition, and that it would ultimately win Guevrekian the jurors’ Grand Prix. In the Jardin d’Eau et de Lumière visitors were first detached from the space, but a forced one-point perspective of the installation engaged them immediately, collapsing vision and spatial experience within a self-referential aesthetic structure.

Guevrekian’s contribution was not ready until mid-July, but despite being nearly three months late, it was what Forestier had been hoping for: a modern, yet Persian, garden that beyond the mere employment of traditional decorative elements; instead the Garden of Water and Light was a space abstracted from its surroundings. It was an architectural statement within and against nature.

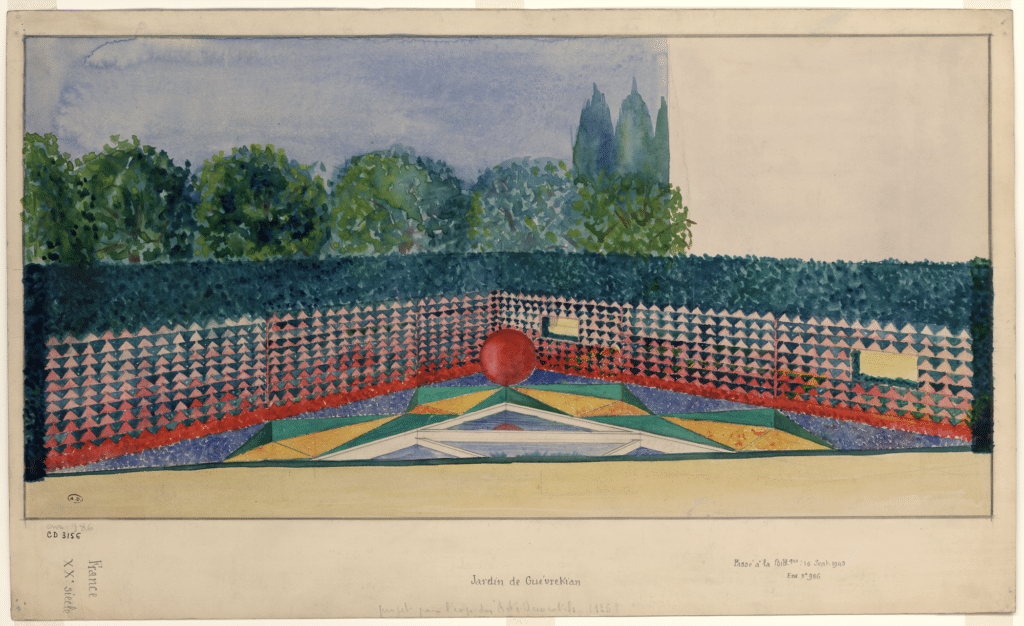

Among the many visitors to the fair that year were Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, wealthy patrons of the arts and owners of the fabled hôtel particulier at 11 place des États-Unis (site of notorious parties with Jean Cocteau, Luis Buñuel, and Man Ray, and an extravagant interior designed by Jean-Michel Frank). At the time, the couple were collaborating with Mallet-Stevens on the design of their holiday villa in Hyères on the Côte d’Azur. After seeing Guevrekian’s installation, the Vicomte de Noailles (who had earlier commissioned an abstract garden of boxwood and colored gravel for the grounds of his Paris home) wrote to Mallet-Stevens, saying, ‘I very much liked this garden at the Decorative Arts and would gladly ask [Guevrekian] to design one for here, if you think this kind of thing would amuse him.’ [3]

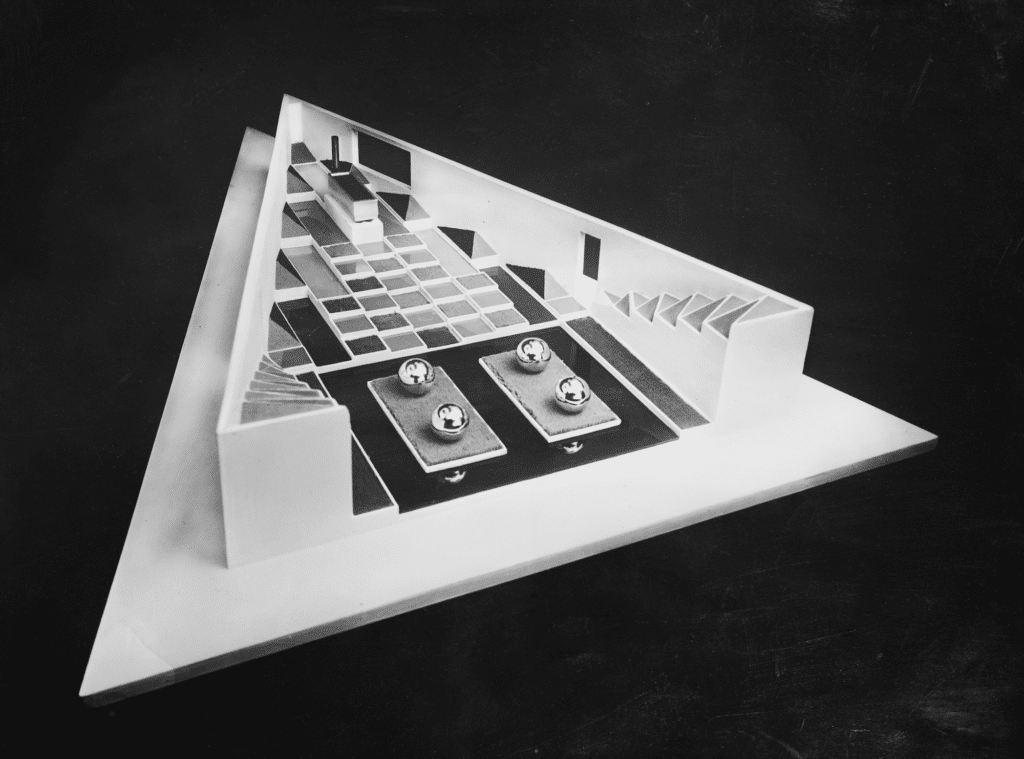

This idea did indeed amuse Guevrekian, and he soon accepted the commission to design a garden of 120 square meters on another triangular plot in the southeast corner of the Noailles’ estate in Hyères. Besides its bounded geometry and the fact that it was designed to be viewed from a terrace, outside its perimeter the garden had many other elements in common with the earlier expo installation – the plot was framed by crisp concrete walls, the ground plane was tilted, and flower beds filled with brightly colored tulips were arranged in a mosaic checkerboard pattern, again framed by white concrete dividers. There were some differences, though, notably the two orange trees that were planted symmetrically just in front of its entrance, and the sunken pool of water that marked the central axis. In lieu of Barillet’s spinning ball, the Hyères garden featured a bronze sculpture by Jacques Lipchitz, La joie de vivre – a dancing figure with a large guitar, which rotated every four minutes on its mechanised base. [4] The statue was not part of Guevrekian’s original design, and after its installation, the perimeter walls of the garden were subsequently lowered, to make both the statue and the geometry of flowerbeds more visible.

Upon its completion, the garden immediately became a celebrated modernist monument, and it even found its way onto celluloid, featuring in a number of sequences in Man Ray’s 1929 surrealist film of the Villa Noailles, Les Mystères du Château de Dé. Sadly, these stills, together with a number of photographs of the garden taken by Man Ray and by Thérèse Bonney, were soon all that remained of the garden. By 1934, the Vicomte’s gardeners had filled the entire triangular plot with low-maintenance aloe, having grown tired of the upkeep the garden required. Later, in the 1930s, the site fell into total neglect. It was only in the 1990s that the city of Hyères – which now owned the estate – renovated both the villa and its garden, even if the troublesome tulips were replaced with hardier marigolds.

The essay is an excerpt from Gabriel Guevrekian: The Elusive Modernist, by Hamed Khosravi, published by Hatje Cantz. Pre-order through the publisher’s website or visit www.guevrekian.org.

Notes

- Beyond his official role as the curator of the Paris parks system, Forestier was a landscape theoretician. In 1920 he published Jardins: carnet de plans et de dessins, in which he described and illustrated structures and formal principles of various gardens of the world. There he dissected the influence of the Persian paradise garden into main streams: the Greco–Roman and the North African–Spanish, both of which he would employ in his designs. Jean-Claude Nicolas Forestier, Jardins: carnet de plans et de dessins (Paris: Émile-Paul, 1920), p 51.

- Fletcher Steele, ‘New Pioneering in Garden Design’, Landscape Architecture 20 (1930), pp 159–77.

- Charles de Noailles to Robert Mallet-Stevens, 5 November 1925. See Cécile Briolle, Agnès Fuzibet and Gérard Monnier, La Villa Noailles: Rob Mallet-Stevens (Marseille: Editions Parenthèses, 1990), p 62.

- Dorothée Imbert, The Modernist Garden in France (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 1993), p 135.