Gio Ponti: ‘Come for Porchetta’

The Milanese architect Gio Ponti typically arrived at his office very early in the morning and would use the quiet interlude before his colleagues appeared to write a succession of letters – to friends and associates, to clients and contractors, to his associate editors at Domus or Stile, to his fellow architects Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Josep Antoni Coderch, and to any number of other important people, not least the Italian president, the Pope, even the Queen of England. An Italian archive of his correspondence, both sent and received, contains more than 99,000 letters exchanged with over 6,400 recipients.

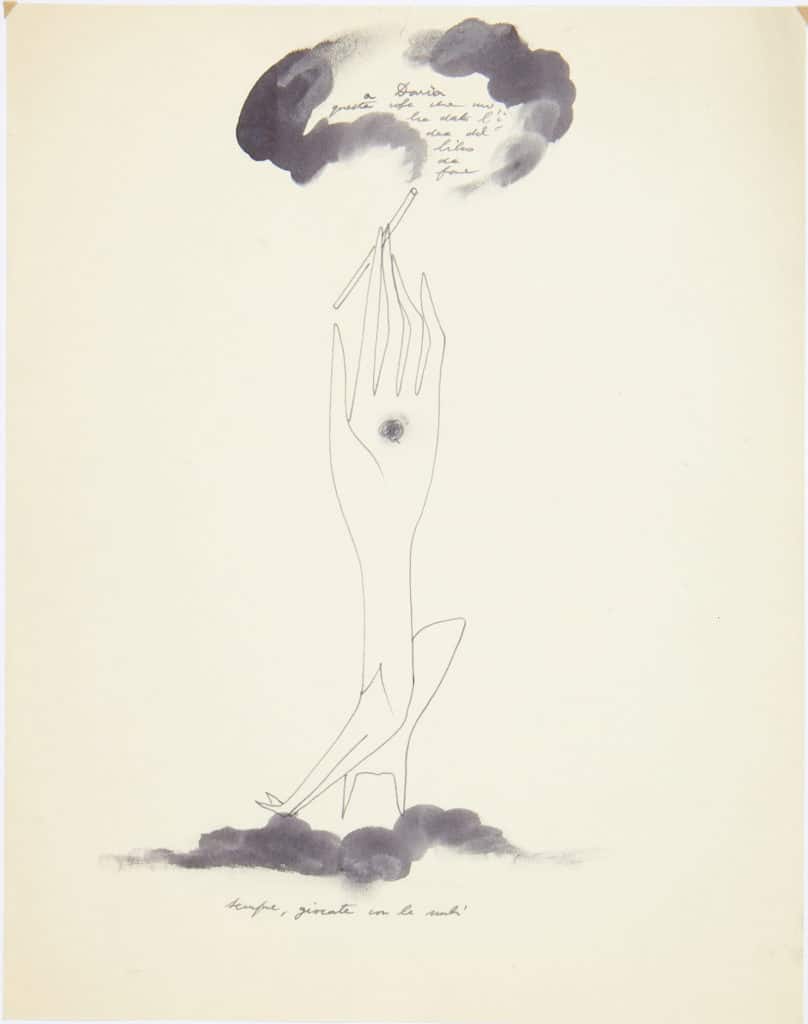

‘My happiness, my love, my life, my sunny rainbow, my sweetheart, my kitty’ – these are the words with which Vladimir Nabokov would begin and end letters to his wife Véra. Ponti’s own prose was no less effusive, but what distinguished his seemingly more heartfelt offerings was that he expressed emotion not so much in words as in pictures. Nowhere is this more apparent than in several letters he sent to Daria Guarnati, publisher of perhaps his oddest book, Expression di Gio Ponti, the eighth volume of her Aria d’Italia series, published in 1954.

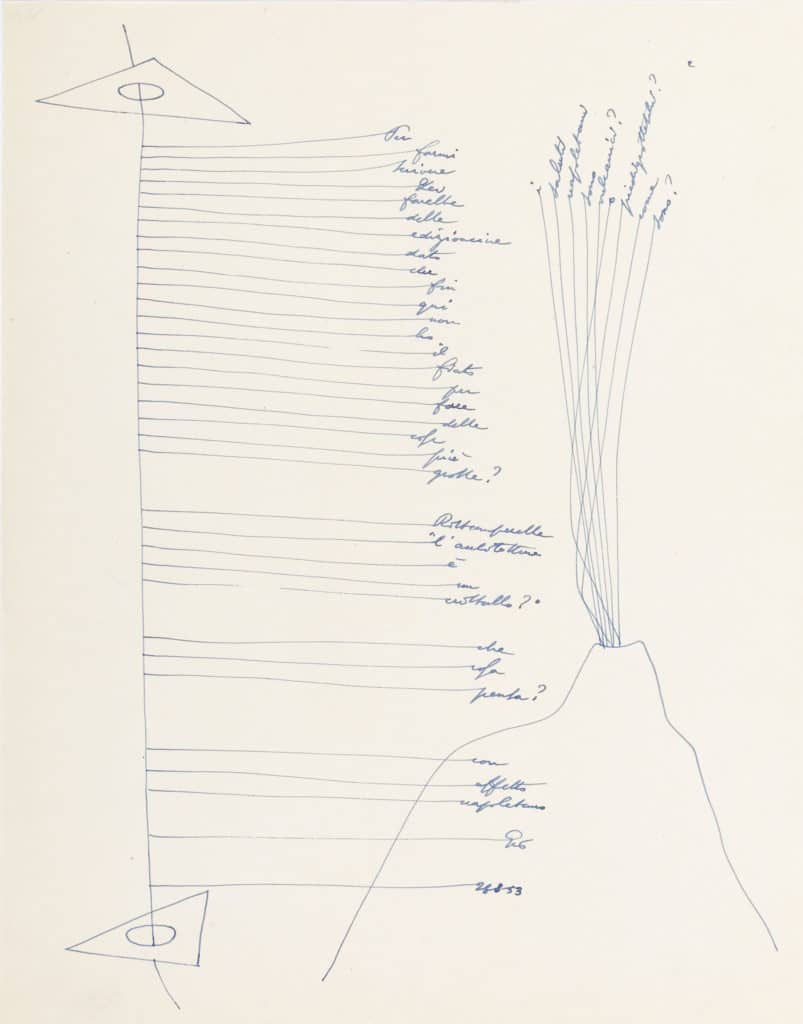

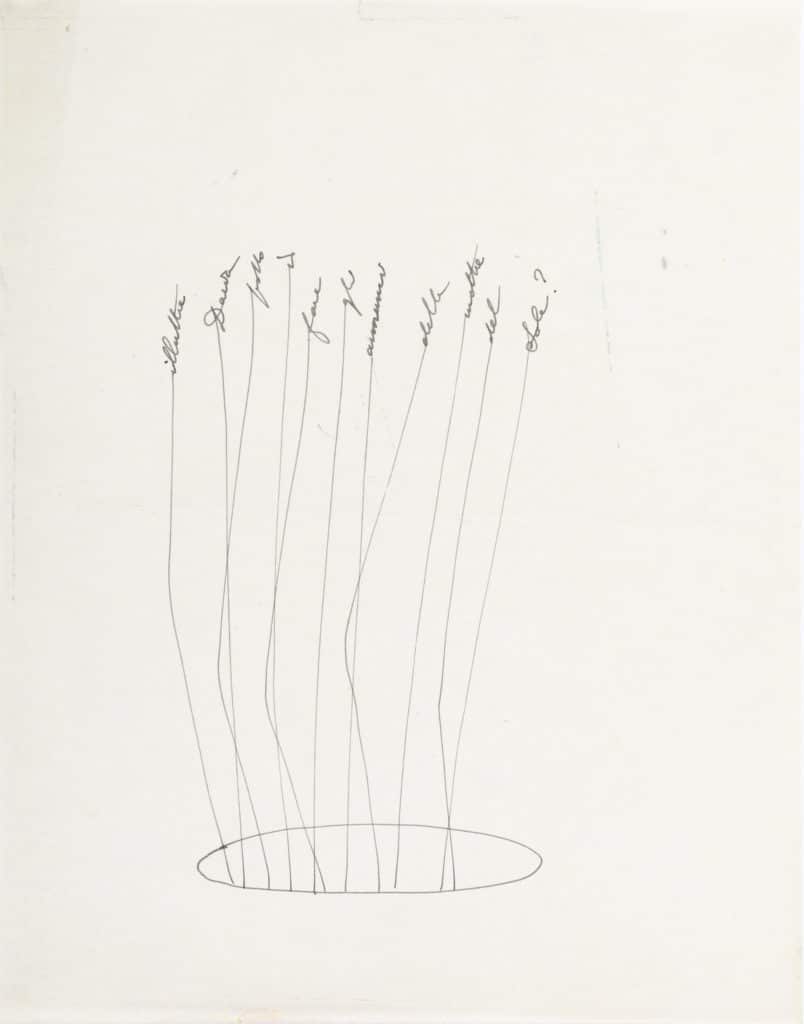

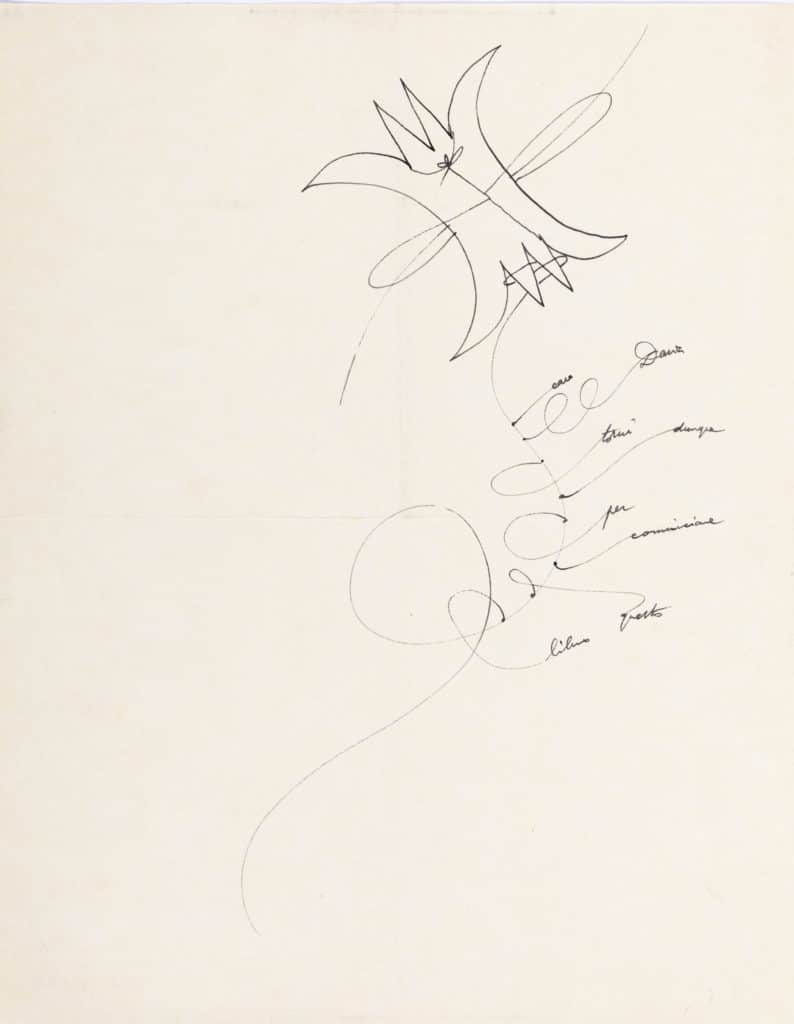

The exuberance of the drawings in these letters seems to suggest they formed the backdrop to a consuming affair, for among them we see words springing out of a fine female profile, or extruded from an especially elegant hand, or – presumably as the passion escalated – springing from the fuses of a number of sticks of dynamite, and then, even more forcefully, as the eruptive magma of a turbulent volcano.

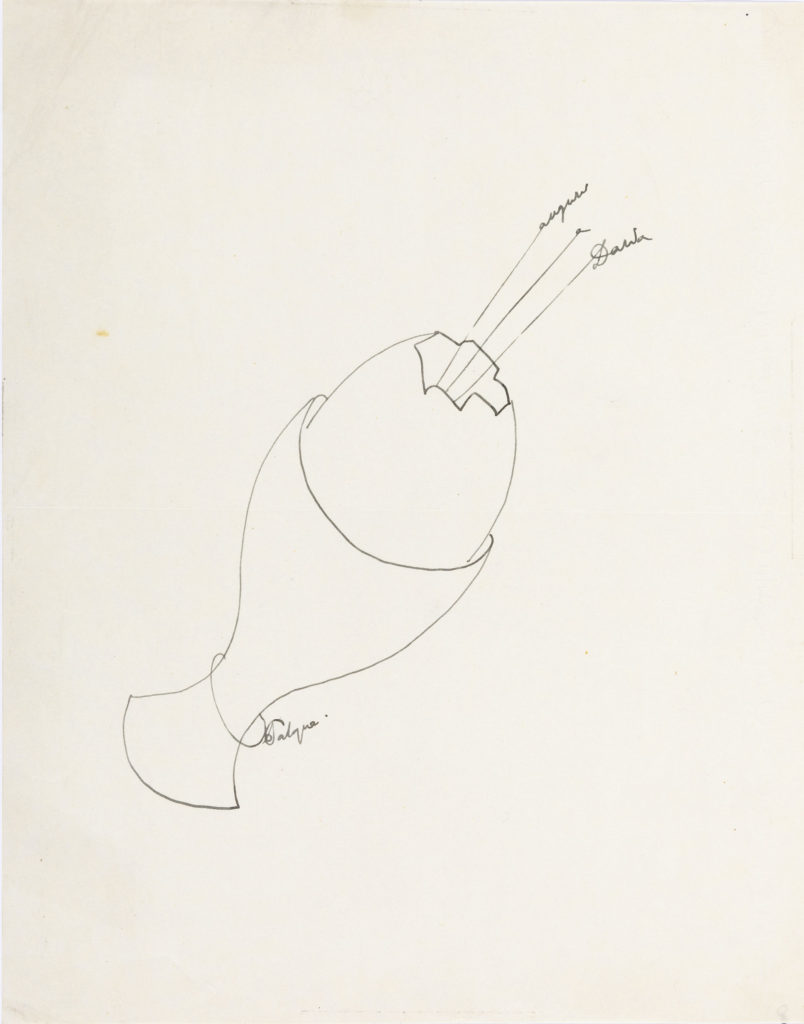

In reality, however, the words themselves and the prompt for their writing were often quite mundane. ‘Can we print it in black ink?’ ‘Would you publish small editions?’ Or ‘Come for Porchetta’, as an invitation to talk further over dinner. In other missives we find him debating the titling of a chapter in his book or discussing the arrangements for a trip out of town – everyday details that in some way are also reflected in the associative character of his less explosive visual tropes (words hung beneath sheets of washing line, for example, or perhaps most sweetly – in its ordinariness – in the three-word letter he formed out of a boiled egg in its cup).

As much as these charm us, there is also an undeniable aesthetic in these letters – a joy that comes not form the words but from the beauty of the sinuous, looping line. For this line follows, traces, creates or transforms, giving the rhythm of a poem to every word it spells out, lending it new meaning and making it even more beautiful. With the line, Ponti turned the most banal of letters into an elegy.

Yet is there also perhaps something more shaded an uncertain here, as though Ponti’s real voice could only find itself through equivocation? Something in those impeccably wrought lines that then tail off into banal words; in the forms of delicious intimacies that then never move beyond their promise? It is as if Ponti – that playful chameleon of Italian design – had danced long enough between textiles and concrete, between elegiac history and modernist rupture, between the editorial authority of Domus and the mystical opacity of In Praise of Architecture; even between form and word. Could it be that the very ambiguity of Ponti’s lapidary form encapsulates an uncertainty about which all of the different selves, and all the possible Italys, he should be really be addressing?

– Niall Hobhouse