Guy Debord—An Art of War

An Arsenal of Situationist Practices: The New Theatre of Operations in Culture

– Laurence Le Bras and Emmanuel Guy

The following is an extract from the book Emmanuel Guy, Laurence Le Bras, and Bibliothèque Nationale De France, Guy Debord: Un Art de La Guerre (Editions Gallimard, 2013), pp. 92–96 published on the occasion of the exhibition ‘Guy Debord: an art of war’, presented by the Bibliothèque nationale de France on the François-Mitterrand site, from March 27 to June 30, 2013. It is here translated by Jane Yeoman and illustrated with material from Drawing Matter Collections.

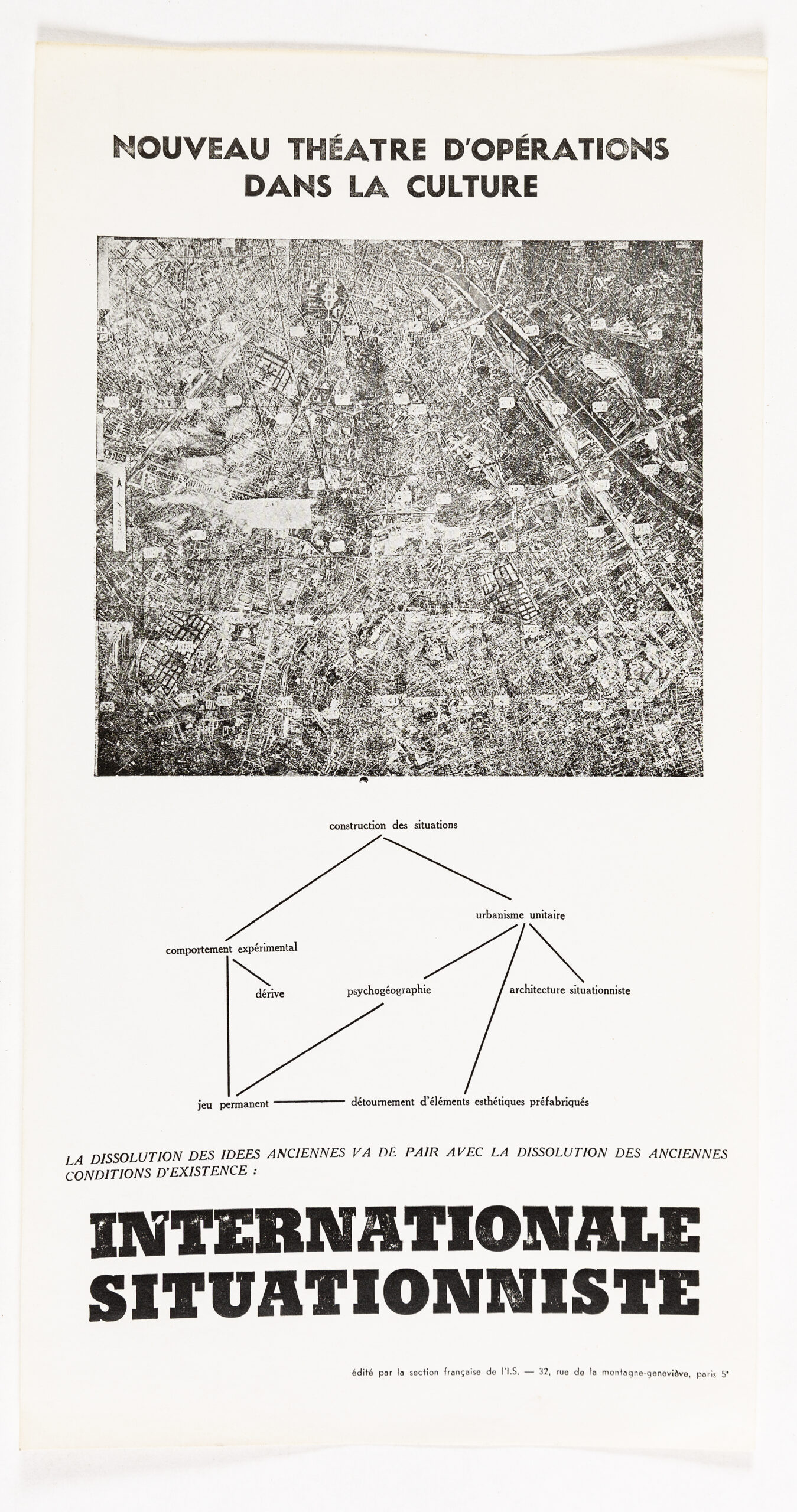

The New Theatre of Operations in Culture (1958) reveals the position and arsenal of the new Situationist International, and is styled in the form of a military staff officer’s route plan. With the title, the group clearly states its avant-garde ambition (‘new’), its strategic perspective (‘theatre of operations’) and its chosen battlefield (‘culture’). The leaflet develops the spirit and import of the situationist project in a controlled graphics composition.

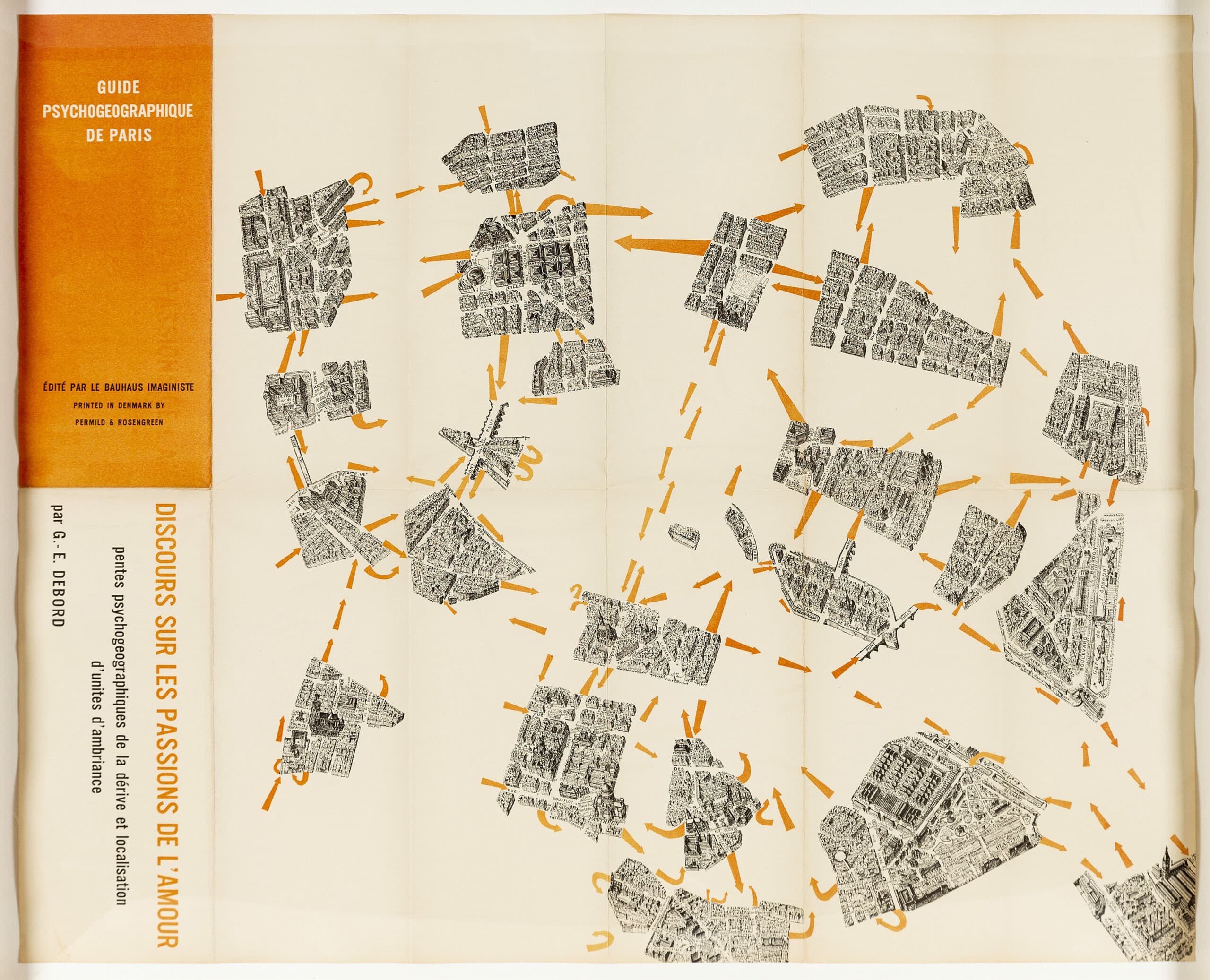

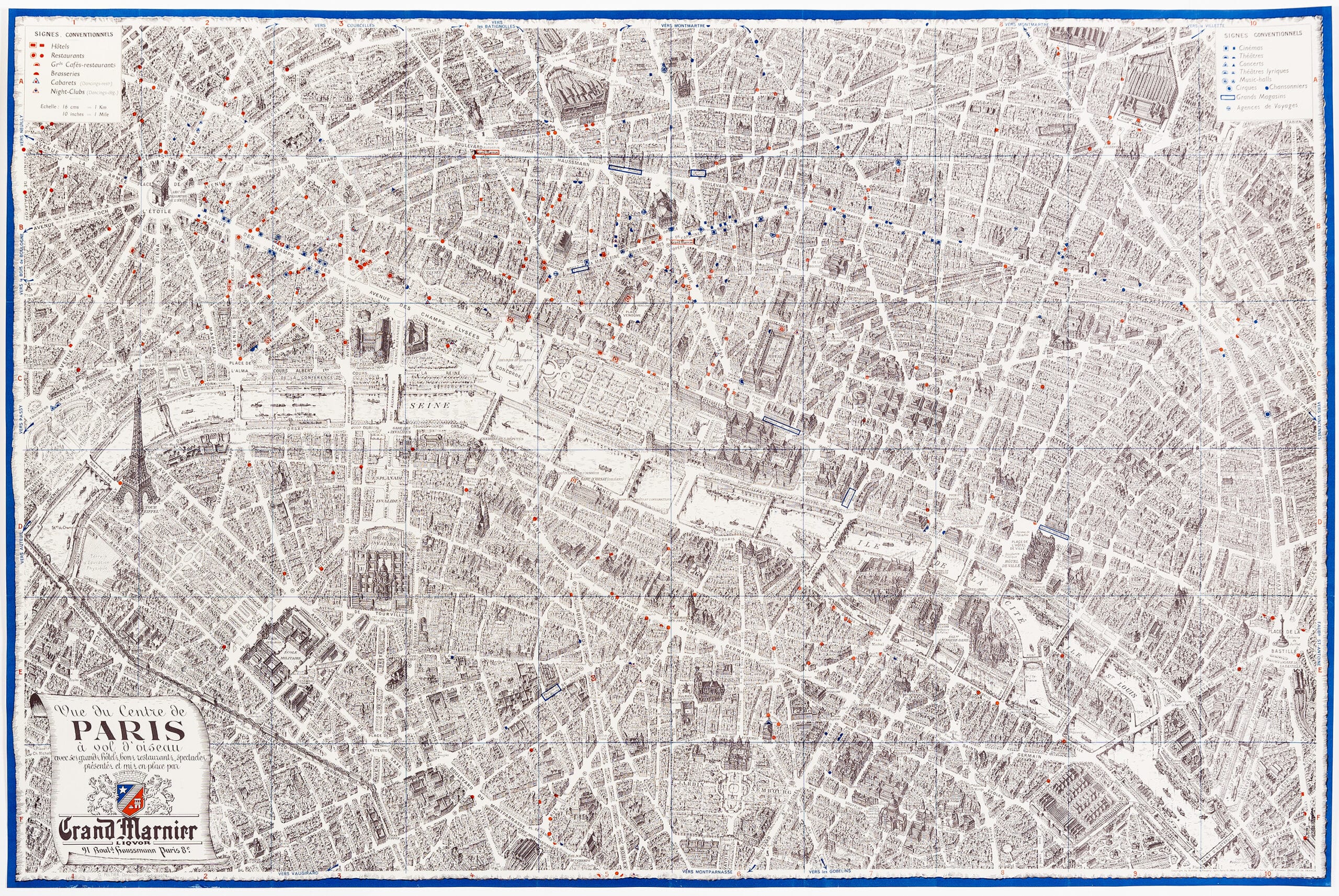

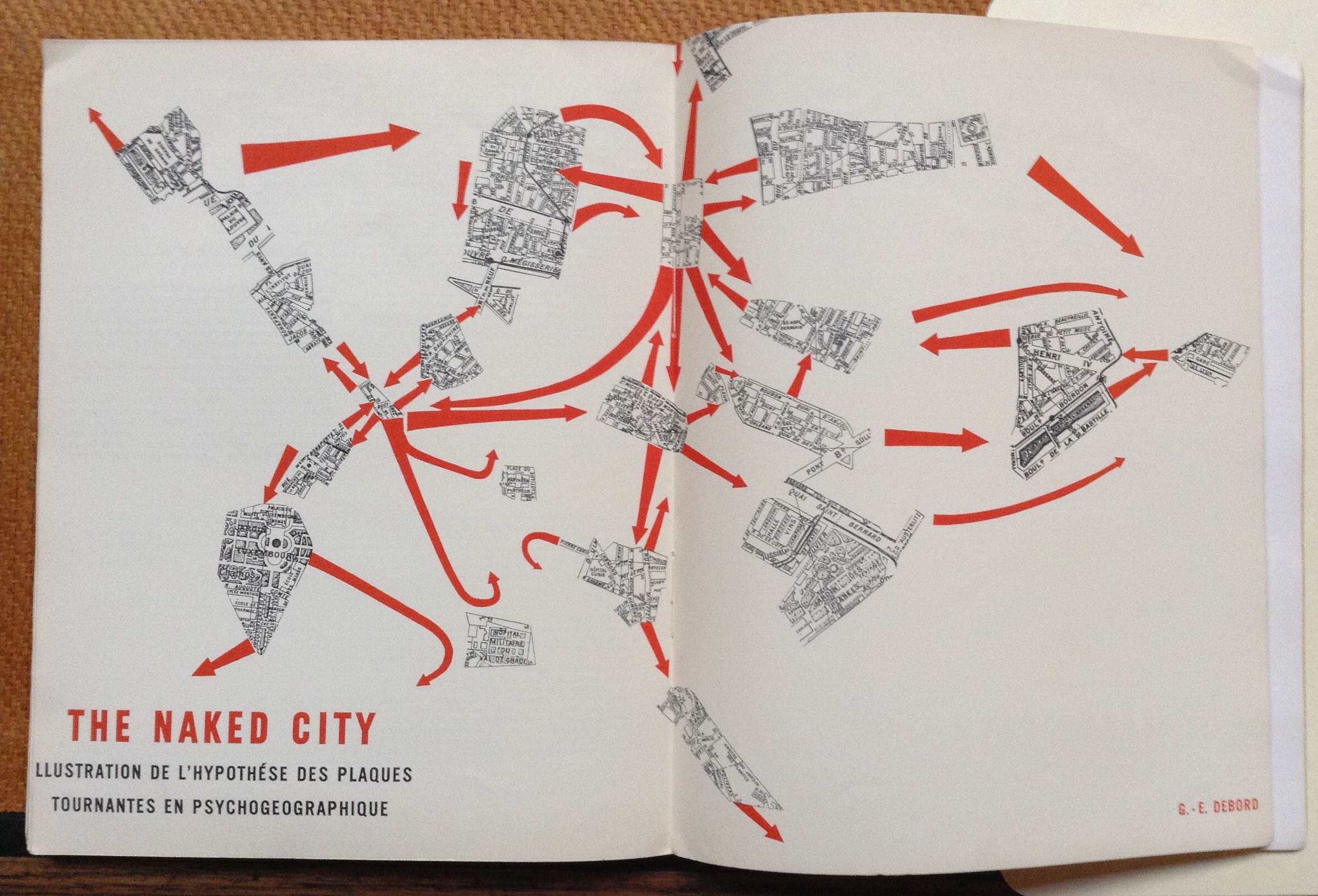

The prominent aerial view signals the Parisian anchorage of the French section of the Situationist International, but above all, testifies to Guy Debord’s interest and fascination with maps. In May 1957, the year before The New Theatre of Operations in Culture was published, Debord had his renowned psychogeographic maps printed in Copenhagen, employing other figurations of urban space seen from the sky: fragments of a Paris map from a bird’s eye view, designed by Georges Peltier.[1] Later, in his films—La Société du Spectacle (1973) and In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni (1978)—Debord included aerial views of Paris in the form of low-angle photographs. The close relationship that such maps hold with the memory of a city is well-known, but their meaning also indicates a strategic perspective. Thus, in March 1988, Guy Debord stressed to Floriana Lebovici the need to include maps in the next edition of Clausewitz’s work, On War: ‘It is impossible to understand the large part of strategic issues without reference to geography’.[2] If you want to go to war, therefore…ensure maps have been prepared.

Weapons too are needed: these are the situationist practices, presented in the leaflet, The New Theatre of Operations in Culture, in the form of a diagram, which underlines the coherence of the project. No reading direction is necessary because everything fits together. Nevertheless, it is the permanent game that seems to constitute the entry point from which the plan deploys: applied to culture, it leads to diversion; combined with experimental behaviour in space, it gives rise to drift. In the end, the game—via psychogeography—is at the foundation of unitary urbanism and situationist architectural projects. The whole contributes to the construction of situations—a kind of situationist grail, or the ultimate point of a strategy which begins in the game.

The Permanent Game

Permanent play is first and foremost a way of living and escaping ‘l’esprit de sérieux’—of which it would be wrong to accuse the young situationists: the foundation of a dialectical relationship with the world, where everything must be turned upside down if everything is to be rebuilt, involves taking distance from current social conventions, in the aim of their definitive overthrow. The situationist homo ludens, marked by Dutch medievalist Johan Huizing’s [3] essay on the social function of games, based his relationship with others on the pleasure of the game and its subversive potential. Furthermore, thanks to permanent play, Debord intended to attack in places where the spectacle was seen to be most effective in alienating consciences—i.e. within the leisure society, prosperous after the war. With this, it was a question of taking back from the spectacle what the spectacle itself had stolen and frozen either on cinema screens, the glossy paper of magazines, or in funfairs: play, adventure, pleasure.

Diversion

Diversion consists of reusing in a new context—without mention of origin—pre-existing elements of culture, such as texts, films, advertising, news, comics, etc. Theorised since 1956, diversion is the trademark of Guy Debord and that of the situationists, yet also shares many similarities with the cut-up, developed by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin in their hotel on rue Gît-le-coeur at the end of the 1950s. Such re-use could consist of simply integrating an intact fragment into a new creation, or modifying a word, a frame, or a speech-bubble in an existing work. Guy Debord’s archives reflect this work: firstly through the reading-sheets, where certain passages are copied and commented on with an enthusiastic ‘div[ertible]!’ in the margins; also, later on, through the vast collection of advertisements, photographs and press-cuttings from the 1970s, all prepared for his films by the filmmaker, with the use of a rostrum.

Diversion was the principle of composition of La Société du spectacle. Debord actualised the theoreticians’ analyses by modifying a word here, or a sentence there, and putting them back into play within the movement of history, rather than freezing them into ready-to-use dogma. He proceeded in the same manner with Marx and the Marxist authors. Through his refusal of the ideology of creativity in the arts and of intellectual property in their commodification, this reappropriation also constituted a putting into practice of the literary communism that Debord and Wolman called for in their speeches in 1956.[4] In putting the past back into play within a new construction, this practice images the revolution: it achieves, in culture and the arts, the great diversion that the situationists intended to implement in life.

Drift and psychogeography

Drift and psychogeography are a form of diversion applied to the space of the city. Drifting is a ‘technique of aimless movement’ [5], which consists of freeing one’s path from the constant constraints of an urban setting and being open to the solicitations of the environment: to the ‘hasty passage through varied ambiances’ [6] —something not so easy to accomplish. ‘The difficulties of drifting are those of freedom’ [7], recalls Debord in ‘Théorie de la dérive’, which he published in November 1956. Inherited from Baudelaire’s walks in Paris or those of Thomas De Quincey in London, and also, of course, from the urban wanderings of the surrealists, drifting was initially a way for the young Debord to survey Paris, place of his birth, and to which he returned in 1951. He was accompanied by his friend Ivan Shtcheglov—he of whom, ‘one could have said that by simply looking at the city and at life, he changed them’. In one year Shtcheglov discovered enough grounds for protest for a century; ‘the depths and mysteries of urban space were his conquest’ [8], Guy Debord later recalled in his film In girum.

The drift, moreover, had a critical dimension which should be placed in the context of urban modernity and the great transformations of Paris in the fifties and sixties. The Urban Planning Code was promulgated in 1954, and many recall the famous instruction, attributed to General de Gaulle during a helicopter flight over Paris, and delivered to his colleague in charge of town and country planning: ‘Delouvrier, put some order in this mess!’ (‘Delouvrier, mettez-moi de l’ordre dans ce bordel’). Something which has not ceased, ever since, to be done. In reverse fashion, the international lettrists and, after them, the situationists, left on a quest within the maze of old streets and the living labyrinth of the Halles, for what remained of the medieval freedom where the ambient disorder, precisely, had led the lost steps of the drifter to adventure. Psychogeography, on the other hand, was conceived as the shaping and the study of ‘the exact laws and precise effects of the geographical environment—whether consciously developed or not—acting directly on an individual’s emotional behaviour’ [9]. It gave rise to the creation of maps where the scattered fragments of plans of Paris accounted for the movement of the drift and the units of atmosphere which they were able to isolate. In the 1960s, the situationists scarcely mentioned drift and psychogeography any more in the pages of their journal; nevertheless, they would learn from both, so as to participate in all the games of insurgency in the Parisian streets.

Unitary Urbanism

Unitary urbanism, finally, and its practical corollary, situationist architecture, occupied a significant place in the group’s early work. Standardly critical of modern architecture (that of ‘Corbusier-Sing-Sing’ [10] or functionalist Bauhaus), unitary urbanism contributed to the convergence between members of the World Congress of Free Artists in 1956—which led to the founding of the Situationist International. The S.I. project is then defined further by Guy Debord and Constant, Dutch artist and co-founder of the Cobra movement (1948-1951). The ‘Amsterdam Declaration’, which they published in the second issue of I.S., sets out in eleven points the synthesis—artistic, scientific and technical—that unitary urbanism sought to implement in daily life:

‘The solution to the problems of housing, traffic and recreation can only be considered in relation to social, psychological and artistic perspectives contributing to the same synthesis hypothesis, in terms of lifestyle.’ [11]

The situationists’ urbanism was unitary both in its means—a collective implementation with no distinction of discipline—and its goals: restore unity in urban life, then fragmented by modern urbanism and the division between work and leisure.

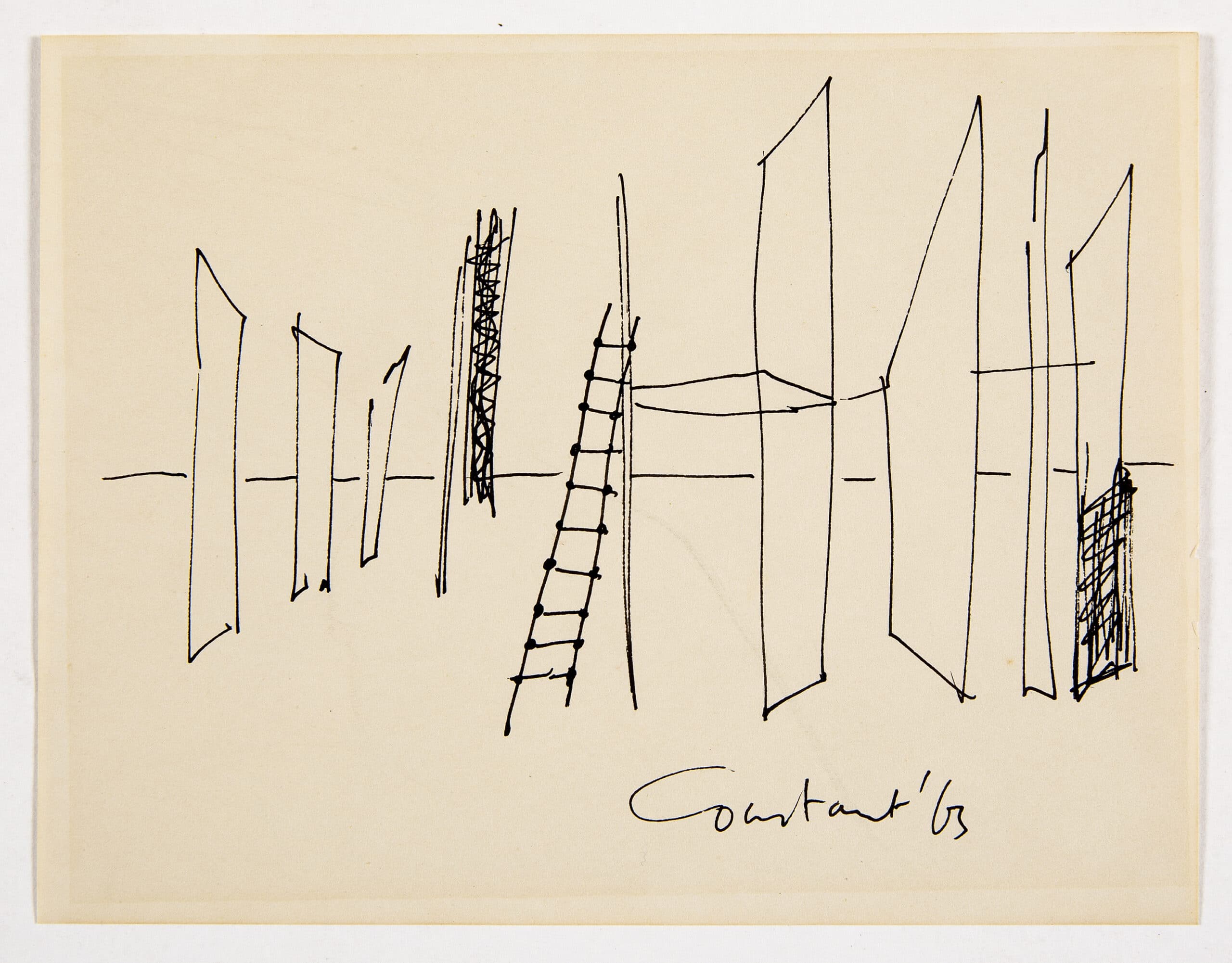

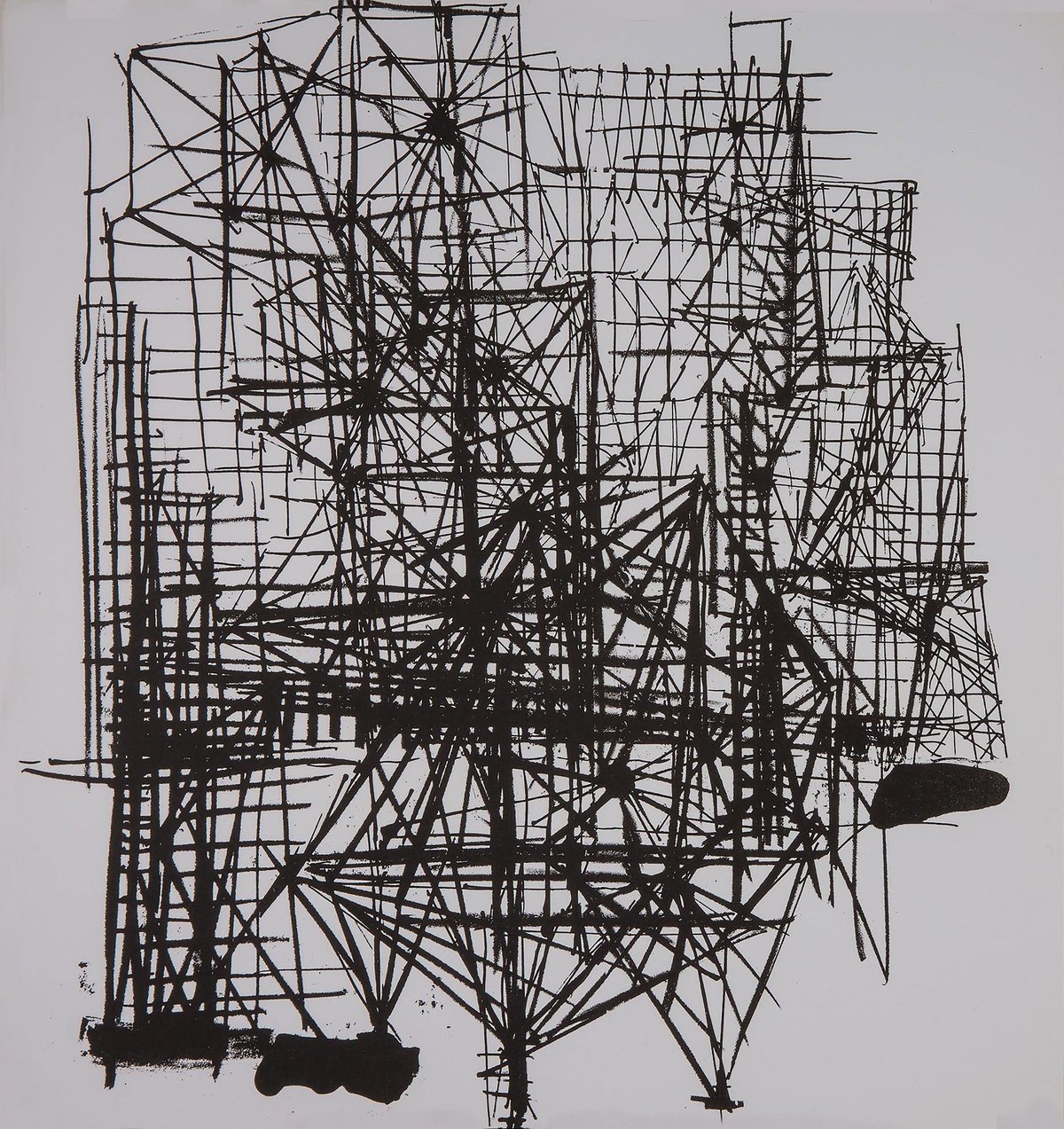

With the ‘New Babylon’ project, Constant threw himself into creating sketches, plans and models, in order to shape the idea. Mounted on stilts, transformable at will, rhizomatic and labyrinthine, ‘New Babylon’ promised a fun and nomadic lifestyle, liberated from the constraints of work through a complete automation of production. A Utopian project if ever there was one, ‘New Babylon’ had little hope of one day being realised. In 1960, Constant resigned from the Situationist International, but continued his research throughout the decade. Guy Debord pursued his projects within the larger theatre of politics.

Notes

- Georges Peltier, Plan de Paris à vol d’oiseau, Paris, E. Blondel La Rougery, 1920.

- Guy Debord, letter to Floriana Lebovici, 19th March, 1988, Correspondance, vol. 7, p. 22.

- Johan Huizinga, Homo ludens: essai sur la fonction sociale du jeu, Paris, Gallimard, 1951.

- See Guy Debord and Gil J. Wolman, ‘Mode d’emploi du détournement’, Les Lèvres nues, no. 8, May 1956. Text reprinted in Oeuvres, pp. 221–229.

- Guy Debord and Jacques Fillon, ‘Résumé 1954’, Potlatch, no. 14, 30 November 1954. Text reprinted in Oeuvres, p. 171.

- Guy Debord, ‘Théorie de la dérive’, Les Levres nues, no. 9, November 1956. Text reprinted in Oeuvres, p. 251.

- Ibid., p. 257.

- Guy Debord, In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni (1978). Film script reprinted in Oeuvres, p. 1377.

- Guy Debord, ‘Introduction à une critique de la géographie urbaine’, Les lèvres nues, no. 6, September 1955. Text reprinted in Oeuvres, p. 204.

- Internationale lettriste, ‘Les gratte-ciel par la racine’, Potlatch, no 5, 20th July 1954. Text reprinted in Oeuvres, p. 143.

- Constant et Guy Debord, ‘La déclaration d’Amsterdam’, Internationale situationniste, no. 2, December 1958, pp. 31–32.

Emmanuel Guy is the curator of the Department of Manuscripts at the Bibliothèque Nationale De France.

Laurence Le Bras is the manager of documentary research at the Bibliothèque Nationale De France.