Helsinki City Theatre: Timo Penttilä on the real purpose of drawings

On his retirement in 1998 as professor of architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, Finnish architect Timo Penttilä returned to Finland, where he soon made the decision to close his architectural practice. In this process he ordered his staff to destroy the entire office archive of drawings and models as well as all photographic records. They carried out his wishes, but his junior partner Kari Lind requested that they delay the destruction of the original working drawings of the Helsinki City Theatre, completed originally in 1967, because Lind was in the process of working on its renovation.[1] Penttilä duly agreed.

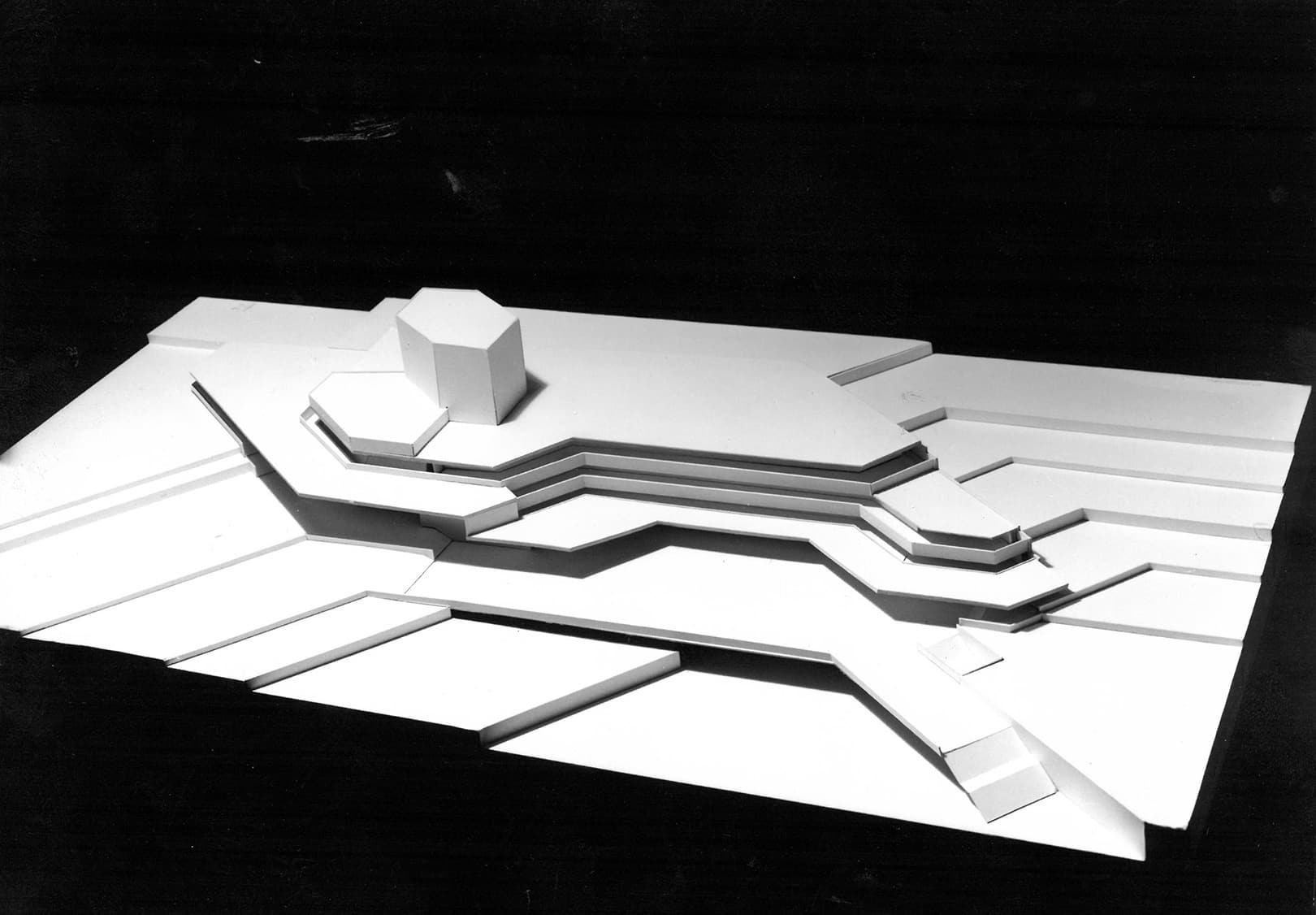

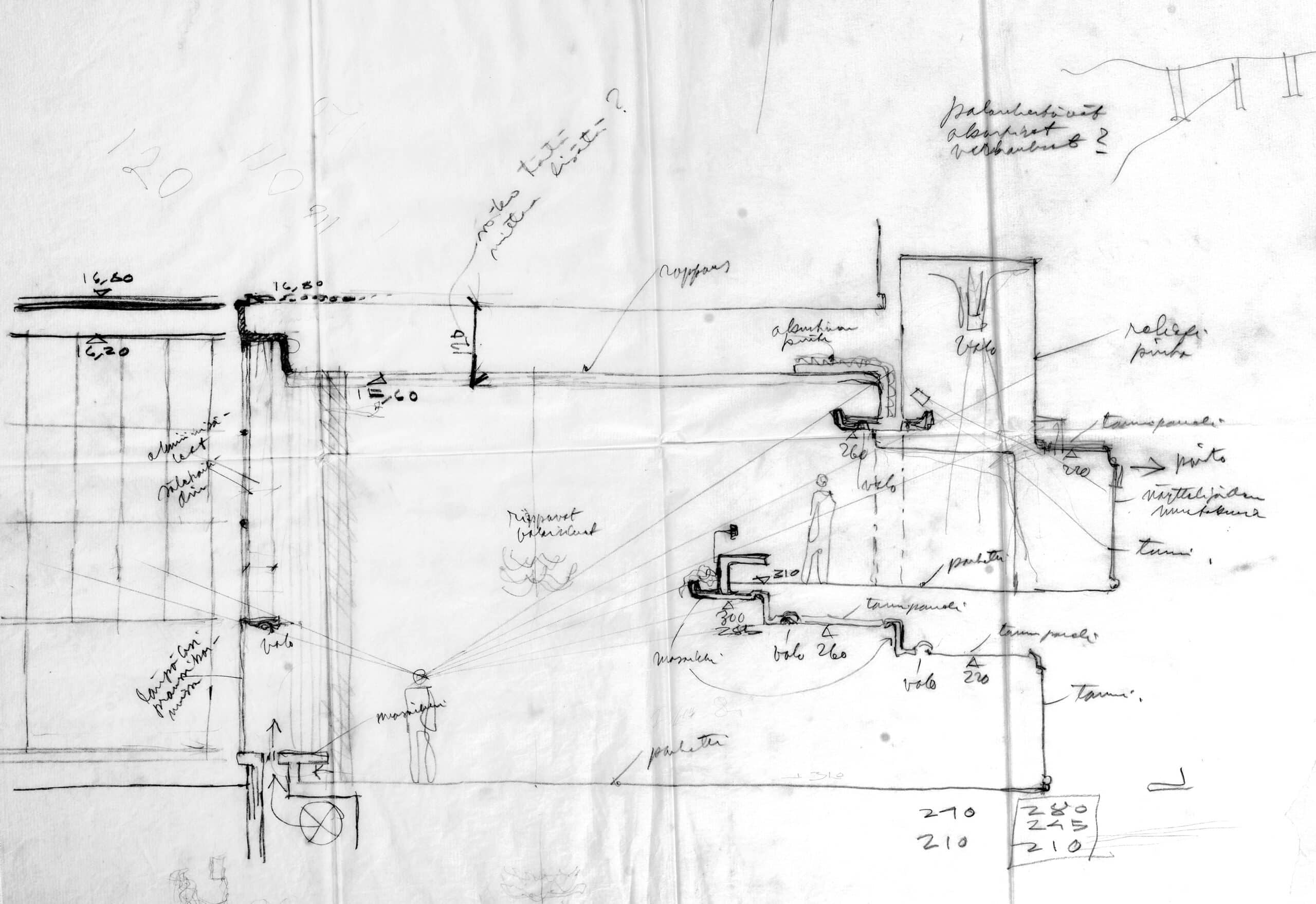

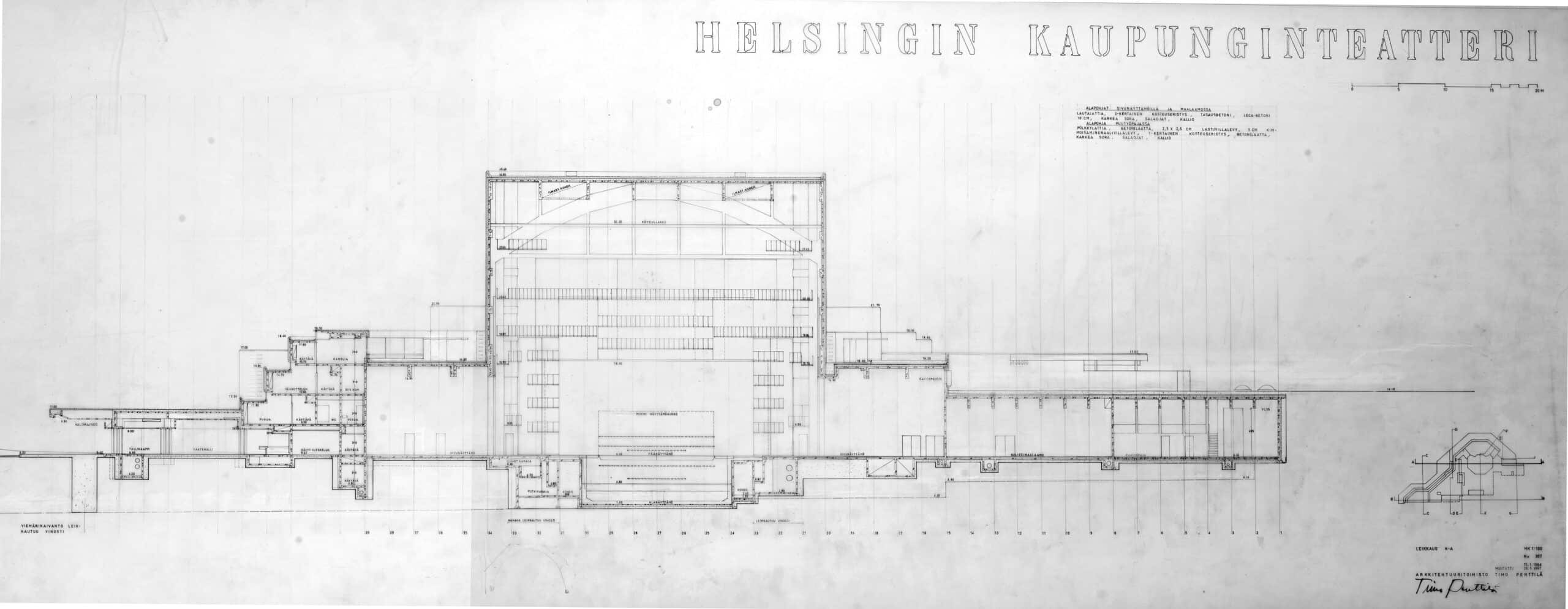

The Helsinki City Theatre commission came to Penttilä after having won the architecture competition in 1960, together with architect Kari Virta. Even before its completion in 1967, the building received a brief mention in the fifth edition of Sigfried Giedion’s canonic Space, Time and Architecture, in a new section titled ‘Jørn Utzon and the third generation’.[2] Penttilä’s theatre, like the works of Utzon, was said to represent a new sensitive understanding of place, not a mere universal abstraction—the building is placed by cutting into the sloping bedrock of its park and waterfront location, not obliterating it but nestling into it. Giedion put the emphasis on ‘[…]empathy with a given situation and an unrelenting maintenance of his own expression’.[3] Such a sensitivity would seem to point to profound studies of ground, profile and ambience—as evident in a cross-section study, one of only a few design sketches preserved.

Penttilä had an antipathy towards architectural theory, in his words, ‘the essence of architectural design lies not in theory and verbiage. Architecture operates with myriads of practicalities and particulars which make the formulation of clear concepts impossible.’[4] Yet, he felt equally that drawings possessed no special significance. For him, the role of drawings had a specific intention, to serve the construction of the building, even arguing that ‘[…]a true architectural experience is not conceivable between a drawing and an observer.’[5] Furthermore, he derided the architectural value of unrealized architectural projects, even the iconic ones known only through drawings, arguing that they are ‘[…]just as far from architecture as science fiction is from science.’ For him, realizability was the most important single criterion in architecture. Penttilä took even a more extreme view towards architectural theory and drawing than his Finnish contemporary, Alvar Aalto, who had argued that ‘God created paper for the purpose of drawing architecture on it. Everything else, at least for me, is a misuse of paper.’[6]

Penttilä passed away in 2011, aged seventy. Lind went back on his word to destroy the working drawings for the Helsinki City Theatre and instead donated them to the Museum of Finnish Architecture. Sifting through the hundreds of technical drawings gives a good idea of the complexity of the vast engineering project but says nothing of the journey from initial concept to final design. Yet in amongst them, one comes across the above-mentioned cross-section sketch, probably left there by accident, showing numerous details that would contribute to the various individual nuances in atmosphere while also showing how to hide technical infrastructure. The whole drawing is annotated with dimensions and recommendations for materials, and is even populated by two figures drawn to scale, with distinct ‘sight lines’ as if witnessing the emergence of the concepts.

Following his retirement from architectural practice, Penttilä spent the rest of his life reading and writing about architectural theory, arguing that justifying his negative views led him to philosophize. His book Oikeat ja väärät arkkitehdit—2000 vuotta arkkitehtuuriteoriaa (True and False Architects—2000 Years of Architecture Theory) was published posthumously in 2013.[7]

Notes

- The Helsinki Theatre was arguably Penttilä’s most noted building. He realized 18 buildings during his career, three of which were based on competition winning entries made before the age of 30. Since his death in 2011 four of his buildings have been demolished.

- Sigfried Giedion, Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967, 5th edition) 691.

- Ibid.

- Timo Penttilä, ‘Teoria ja traditio’ (Theory and tradition) Arkkitehti No. 5, 1980.

- Timo Penttilä, ’Autonomy and authority in architecture’, in Timo Penttilä—Finnish Architecture, Exhibition, Royal Institute of British Architects, London, 2.-18.12.1980.

- Alvar Aalto, ’Artikkelin asemesta’ (In lieu of an article), Arkkitehti, No. 1-2, 1958. Aalto might here be accused of hypocrisy, as he himself wrote numerous theoretical papers, especially in his early career. See: Göran Schildt (ed.), Alvar Aalto in his Own Words. Helsinki: Otava, 1997.

- Timo Penttilä, Oikeat ja väärät arkkitehdit—2000 vuotta arkkitehtuuriteoriaa (True and False Architects—2000 Years of Architecture Theory), Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2013. The crux of the argument in Penttilä’s book is that the ‘true’ architects are in fact ‘false’, and vice versa, because the ‘true’ architect defends an a priori theory, according to which opposition to it is necessarily wrong. The present author has analyzed Penttilä’s view of theory in ‘Ostensive original: Timo Penttilä versus architectural theory’, in Roger Connah, The School of Exile: Timo Penttilä for and against architecture theory, Tampere: Datutop, 2015.

Gareth Griffiths is a retired Helsinki-based architect and urban planner. Additionally, he has taught urban planning theory at Tampere University and architecture theory at Aalto University in Helsinki.

This text is one of the selected responses to the Open Call: Storytellers, Observed—an inquiry into the origin and circumstances of a single drawing (or series of drawings), observing the ways by which each achieves the specific purpose for which it was made. For further information click here.