In the Archive: Alejandro Carrasco Hidalgo

In this series, Drawing Matter invites visitors to write about material in the archive or the libraries at Shatwell that they have viewed as part of their research.

During the peaceful and beautiful train ride that goes from London Paddington to Castle Cary, I dedicated time to thinking about what to see in the Drawing Matter archive. I came to know about it because of my deep interest in certain kinds of drawings—particularly collages in their pre-digital and post-digital forms—and in certain architectural periods and ideas represented in the collection. But the quantity of fantastic material made it difficult to frame and decide what to see in just a day visit.

Heading to the archive with Niall, during a car ride that crossed the beautiful English ‘countryside’, the difficult question came up: ‘What would you like to see? Are there any specific drawings you would like to look at?’. That question, and the conversation that followed, about visitors’ expectations, the most requested drawings and the others that remained overlooked, changed my mind. Perhaps it didn’t make sense to try to control the process; it should become a dialogue that allowed for the exploration of the archive in a more informal way. It would be the discussion and the team’s knowledge about their own materials that would drive us from object to the next. The exercise of looking was suddenly transformed into one of finding within the archive, which resulted in a much more surprising and rewarding experience.

With the wonderful help of Matt, we started to look at things from the only premise available: my interest in collages. The journey started with the magnificent Alison & Peter Smithson collage for their Golden Lane competition entry, a drawing that raises thoughts about the potential of assemblage as a process for continuous intertextuality and the introduction of subjective meaning within architectural expression. The imperfect cutting-out of the building superimposed on to an image of the devastated city of Coventry (standing in for London) after the bombings of Second World War, clarifies the power of subjectivity and biographical inscription within copy-pasting processes. Collage, here, does not just imply a work of objective representation but it rather introduces personal meaning within the process of architectural imagination.

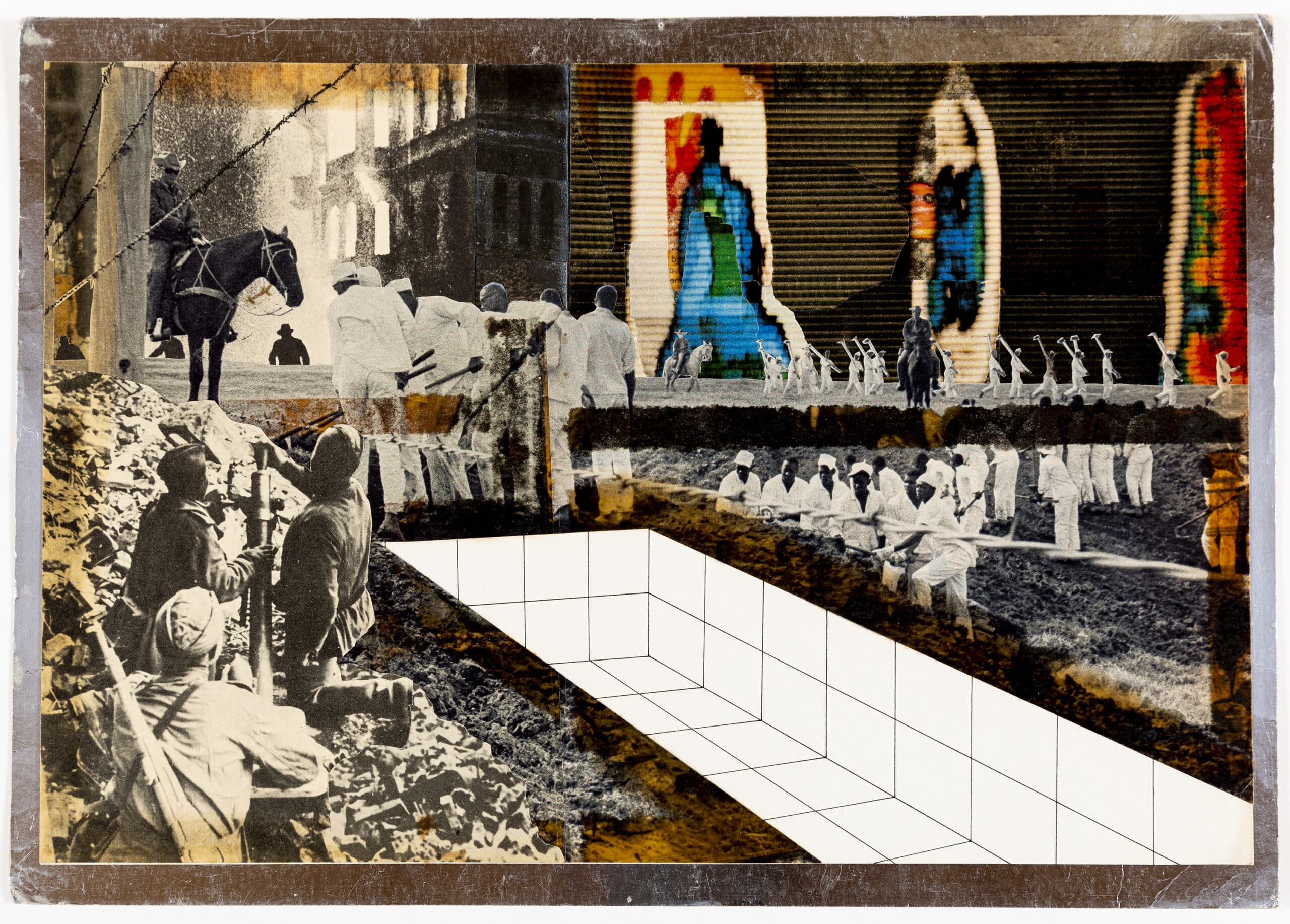

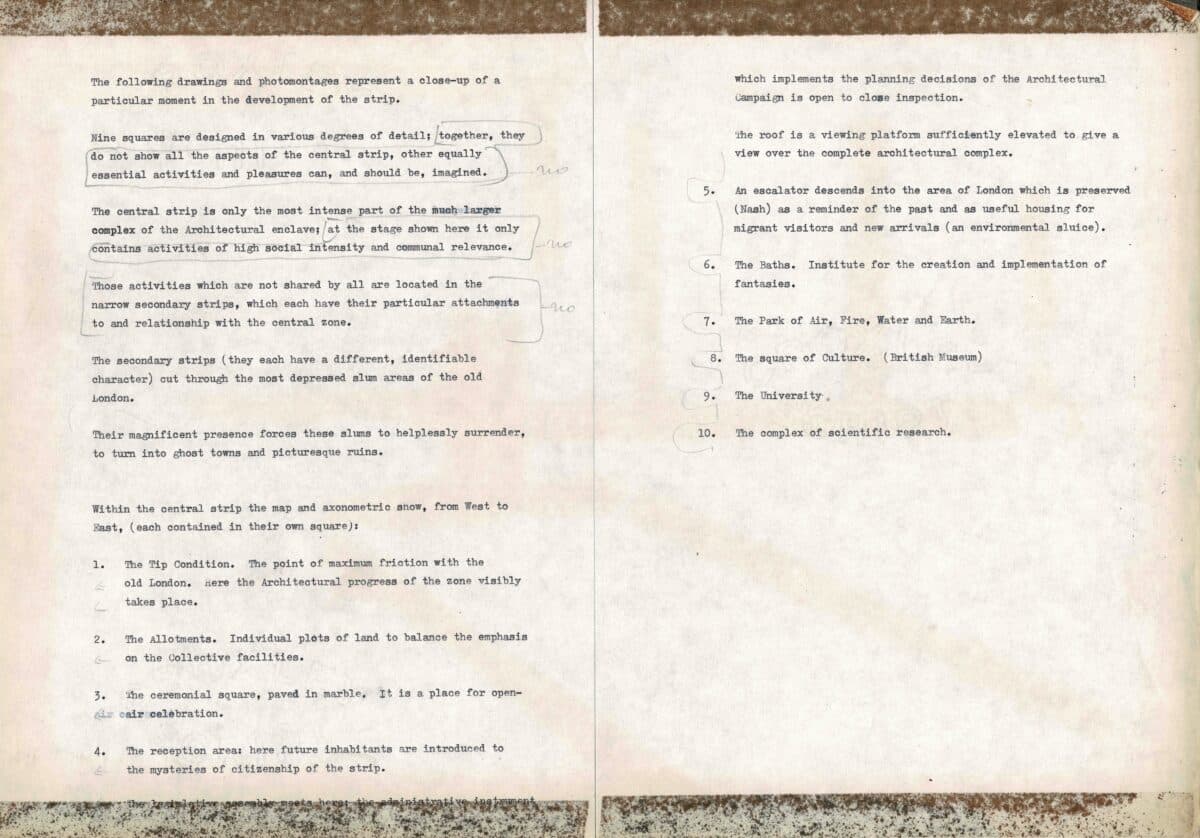

As the conversation continued, we had the opportunity to go through early Rem Koolhaas collages, stopping at the ‘Exodus’ folder, where we found the script drafts for the publication of the project. The presence of the script with corrections, entire rejected paragraphs, and multiple modifications, entangles it with the role of drawing as a communication device, in which the relationship between writing and images remains present even when it is not always visible. Alongside the script was a collage supposedly removed from the group now at MoMA because it was ‘too Superstudio’. If the story is true, it raises questions about the place of architectural representations as the communication of design process in the value chain, where references and influences can be erased if they challenge the value associated with the uniqueness of an object.

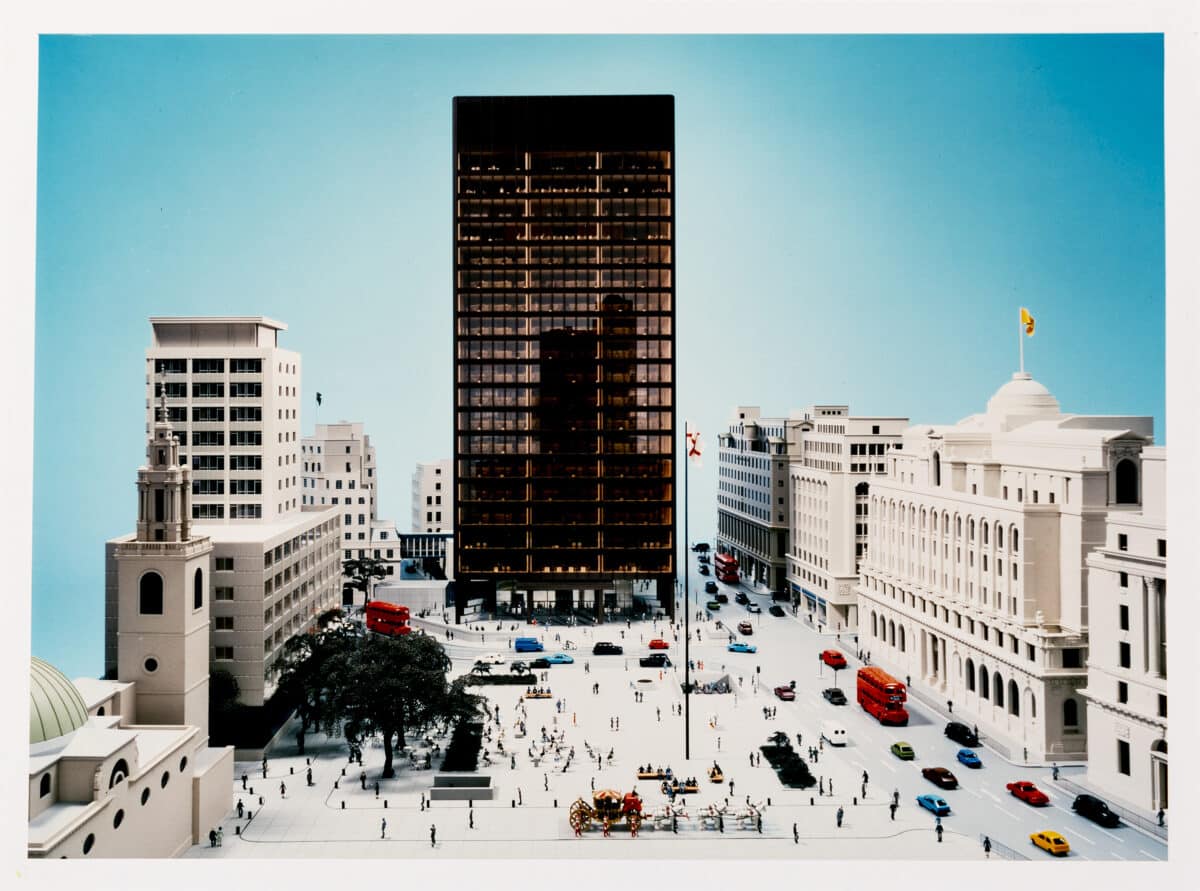

From the importance of narrative difference, we arrived at Mies van Der Rohe’s project for the Mansion House Square. Model pictures, striking for their toy-like and playful qualities, suggested a big contrast to the usual technological and detail-driven Mies representations. Their ‘soft’ appearance may have been attempts to convince the City of the innocent and harmless presence of a tower within central London. Unfortunately, the intended message didn’t get through and the story ended with the tower not being built, eventually substituted by the famous Number One Poultry designed by James Stirling—quite a difference, isn’t it?

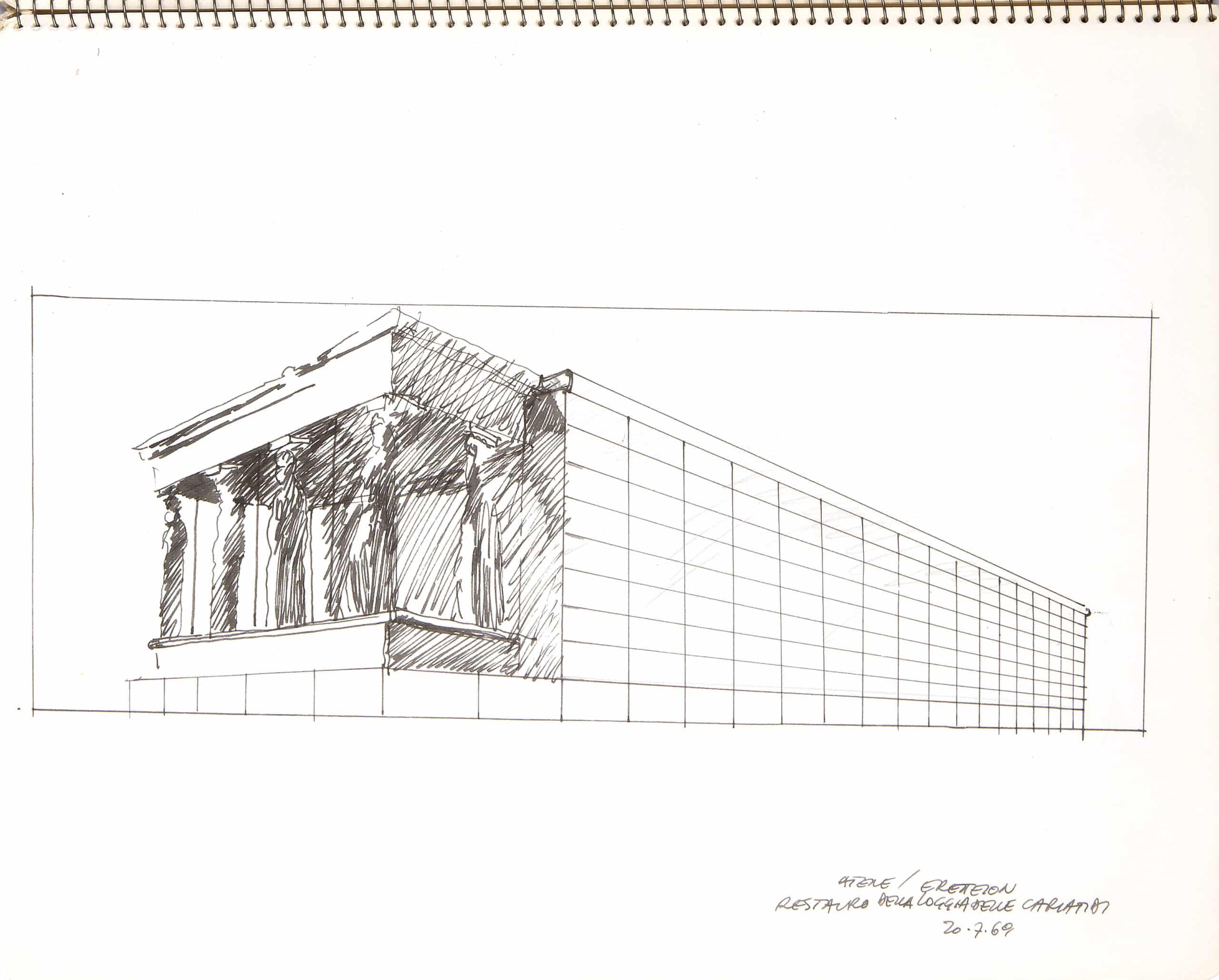

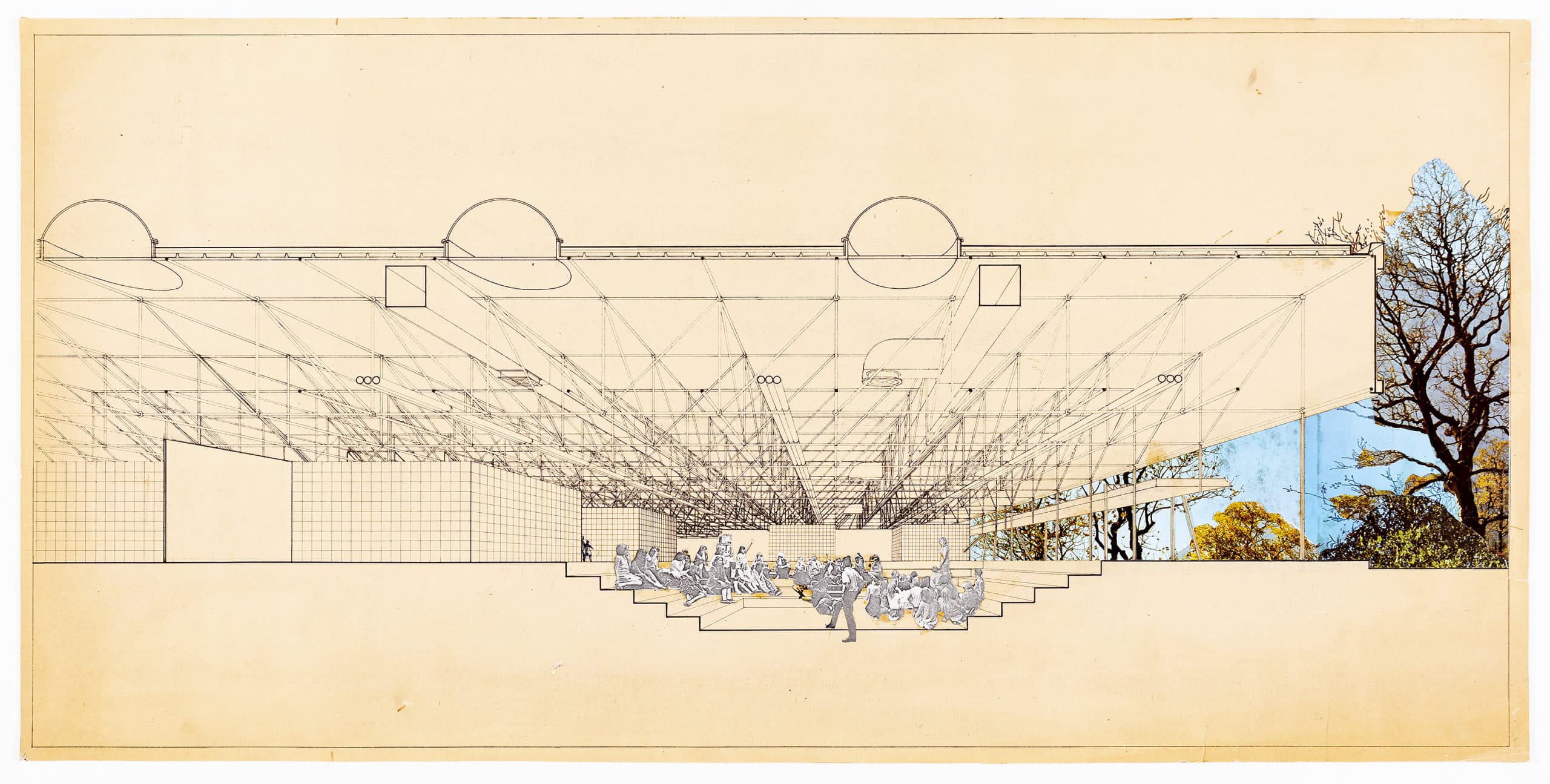

After wandering for a long time around different items, we arrived at the vast amount of material by Superstudio. Their collages constitute a special example because of the multiplicity of media and techniques employed in their conceptualisation and later realisation. Within Adolfo Natalini’s sketchbooks, it is possible to find drafts of the collages that directly anticipate or test how the assemblage should take place. If collage permits recombination and correction, in the case of the project for La Spezia School the process extended into a broader drawing constellation. The collage for the school shows how Superstudio used ink drawings, colour, hand-drawing, and photographic fragments at the same time to highlight properties and drive attention to different places simultaneously.

The most priceless Superstudio item we found was the Collage Chest. This object is a ‘little box of wonders’ employed by the office to keep cut-outs that could be used for their future collages. Beautifully painted by Natalini, the images kept within it are a good example of the authors’ interests and sources that allow us to understand what they were looking at in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Going through the different pages was a complete experience of absence: it was possible to identify where images had been cut-out and introduced into the collages. Divided into five topics (‘Machines’, ‘People, Cars, and Aeroplanes’, ‘Landscapes’, ‘Architecture’, ‘Art’) these visual references are of great importance for seeing the bigger picture behind the final appearance of architectural objects. It is not just the pages themselves, but rather understanding what Superstudio kept and how they filtered and classified the material that reconstructs and connects us to their architectural practice.

During the visit, we came across so many highlights that I cannot comment on all of them, but to just name a few of the others: Cedric Price’s Battersea Station, Aldo Rossi’s Modena Cemetery and Teatro del Mondo, Álvaro Siza’s sketchbooks with multiple drawings for Malagueira and Bouça, John Hejduk’s Cannaregio and North East South West House, and drawings from the Austrian ’60s and ’70s scene by Walter Pichler and Haus Rucker Co..

In the end, I was interested in collage and it was my visit to the archive—a composition of decontextualised pieces (or not that decontextualised)—that regained meaning when put together through dialogue. At the moment I am writing, five days after my visit, I can just wonder what the next conversation in the archive, mediated by different concepts, will unveil for me.

Alejandro Carrasco Hidalgo is an architecture/architectural history researcher at Universidad de Alcalá (UAH, Madrid) and Affiliate Academic at the Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL, London).

– Peter Sealy