The Iterative Power of Architecture’s Absence

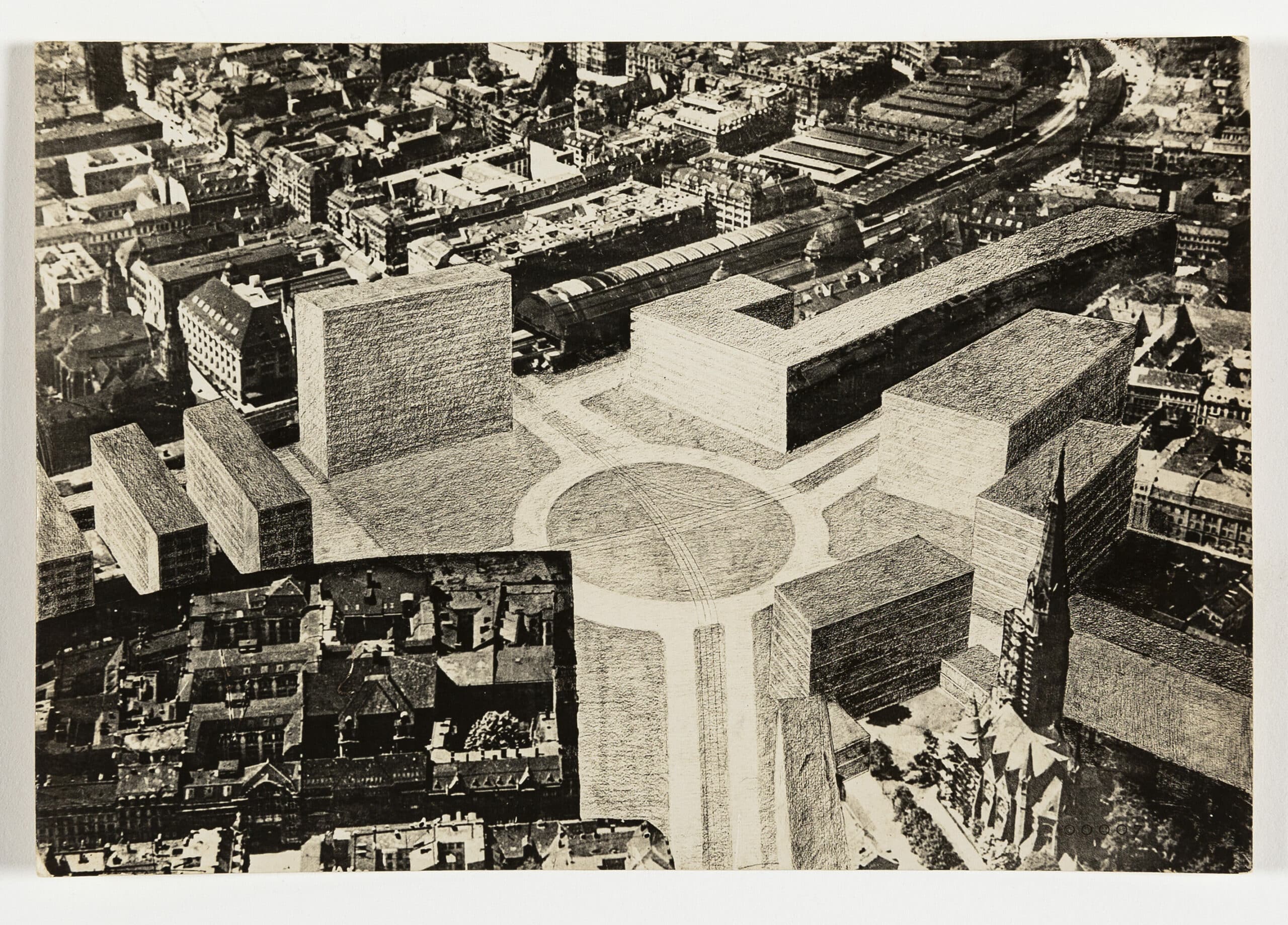

In 1991, the Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron prepared a submission with the artist Remy Zaugg for the Berlin Morgen (‘Berlin Tomorrow’) exhibition organised by the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt, Germany. By surrounding Berlin’s Tiergarten with four new buildings, they proposed to restructure the park – then perceived as a barrier – as the ‘geometric centre’ of the newly reunified Berlin. A photo collage produced by the designers uses a photograph to depict this act of insertion, visually transforming the dark void of the Tiergarten’s tree cover into a connective plinth for the city. The collage makes clear the designers’ intention to operate at a new scale, for the towers dominate their surroundings. However, it deliberately abstains from any significant architectonic communication. Neither the buildings’ materiality, nor their facade treatments are explained. This introduction of a new scale combined with an immaterial (or, impossible) architecture echoes an earlier tradition of Berlin montages, especially Mies van der Rohe’s famous photomontages of his iterative skyscraper designs.

In the text accompanying their project, Herzog & de Meuron and Remy Zaugg make a provocative statement: the ‘form of the building’ is not given by its designers, nor by the economic and technical specialists who guide their work. Instead, it is that ‘which the observer gives the building.’[1] This privileging of subjective interpretation is exactly what the photomontage does: as long as the observer accepts their shape and geographic position within the city, he or she can project an endless series of iterative appearances upon their blank surfaces. This iterative potential is firmly bounded by the slab-like forms given to the four towers and the viewer’s own repertory of architectural appearances. And yet it is precisely the proposed towers’ massive size which renders them useful for the generation of iterative possibilities. Operating beyond the scale at which architecture can easily be assimilated to our expectations, the imagination is forced to take fight: the juxtaposition of blank buildings with the detailed background photograph invites the viewer to imagine further acts of transformative urbanism.

Against the homogenisation of proposal and context brought about by computerised rendering (which began to emerge in the early 1990s), Herzog & de Meuron’s photomontage rejects photorealism through the disjunction between its highly detailed background photograph and the blankness of its proposed buildings. The inclusion of any further detail might risk bringing this speculation about Berlin’s future into too great an actuality. The indeterminacy of the project is key to its potency. In fact, the only thing that is stabilised in Herzog & de Meuron’s highly polemical projection is that which would inevitably change. While their towers were unlikely to see the light of day, the forces re-shaping the newly re-established capital of a united Germany were clearly going to alter Berlin’s fabric immensely. Much of the city visible in the photograph used by Herzog & de Meuron has since been transformed with the less bold, less interesting architecture framed by the 1999 Planwerk Innenstadt (Berlin’s post-reunification plan for its centre), and exemplified by Potsdamer Platz’s ‘starchitecture,’ and the underwhelming buildings erected in the government and embassy districts, as well as the new Hauptbahnhof (central train station).

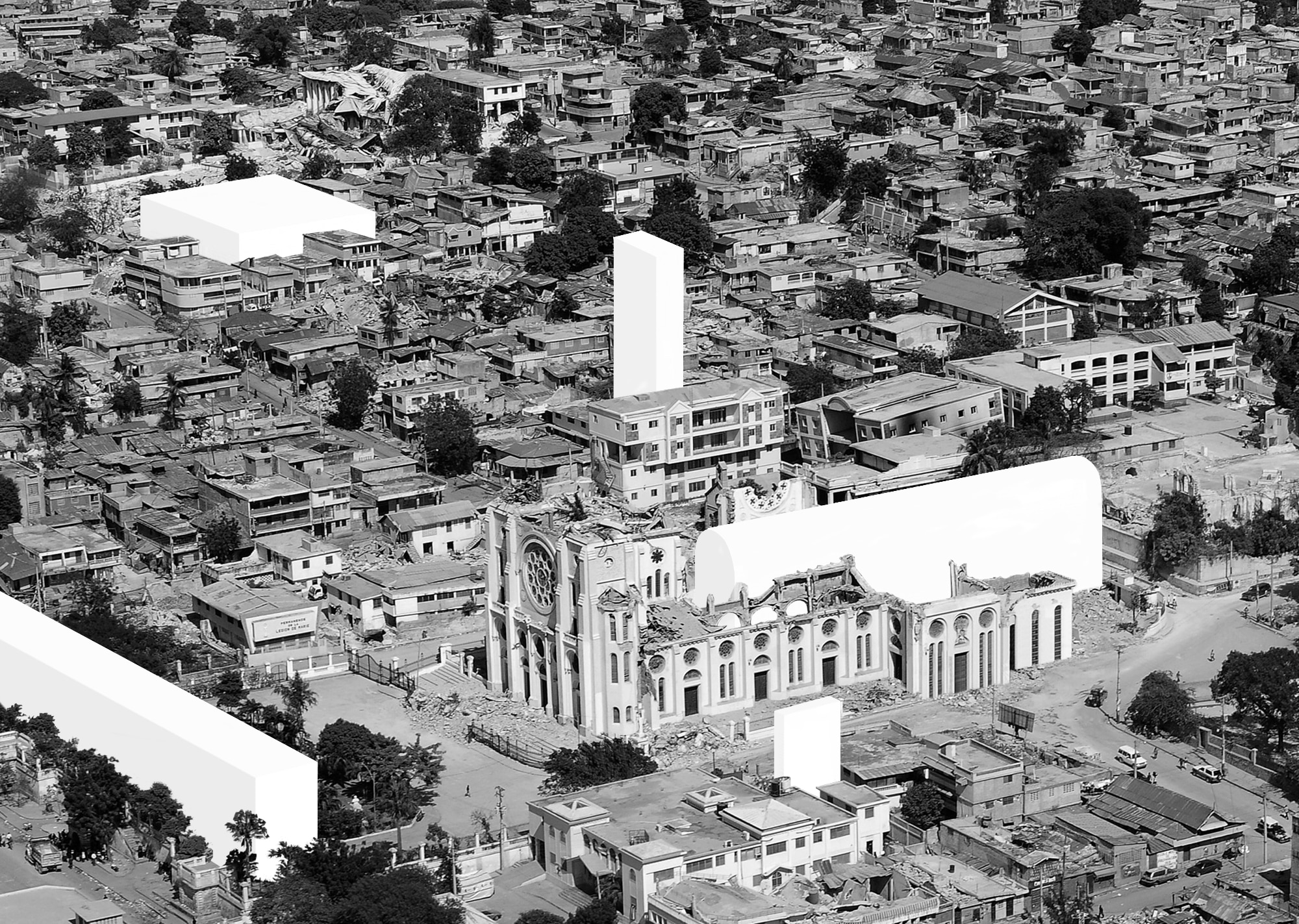

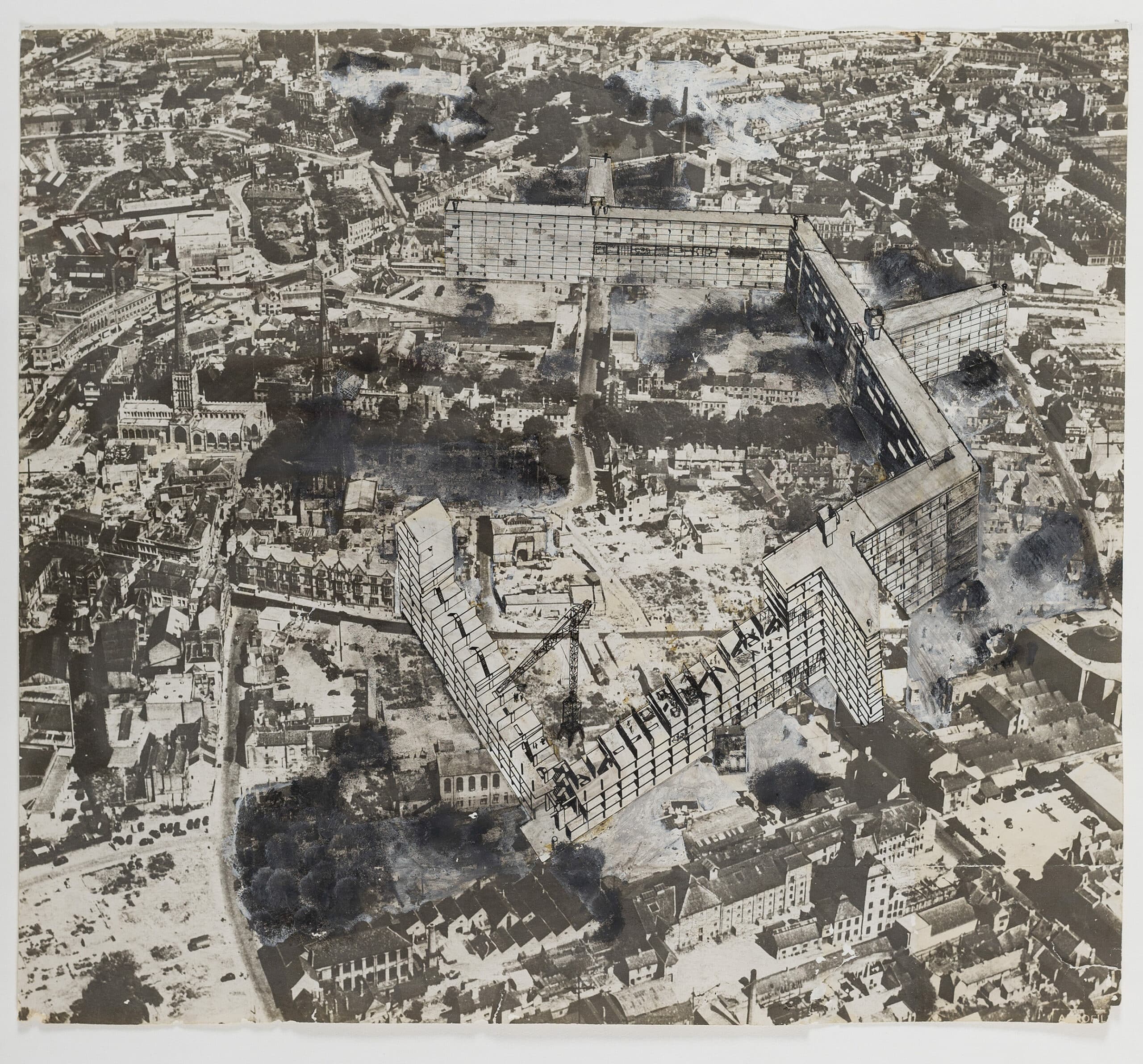

Since 1991, such collages, which use site photographs together with self-effacing architectural proposals have become common in contemporary representation in transatlantic debates and beyond. Examples abound from architects such as Dogma (Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara), Office Kersten Geers David Van Severen, David Kohn Associates, Nicolas Brigand, and Rebecca Kallen Murden, as well as artists such as Christo and Jeanne-Claude. An image produced by École (Nicolas Simon and Max Turnheim) in collaboration with Adrien Durrmeyer for the 2012 international competition to rebuild the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de l’Assomption in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, offers a telling example of this refusal to visually dictate a building’s appearance in an otherwise detailed representation. École’s digital collage reveals the capacity of the architectural project (and specifically, the unbuilt competition entry) to not only project an array of possible futures but also to index an irretrievable past.

The white forms of École’s proposed interventions contrast with the black-and-white photograph of the rubble-strewn city. If a variety of geographic and cultural factors render Port-au-Prince remote to the architects, then the photograph provides them with a ground upon which they can intervene, a body into which they can cut and seek to heal. As with Herzog & de Meuron’s Berlin Morgen photomontage, the level of detail present in the background photograph is matched by its complete absence in École’s proposed buildings. These white, platonic solids are somehow indeterminate and immaterial, unburdened by the scars of physical trauma that mark their surroundings. It is as if the seismic forces that destroyed Port-au-Prince – and the economic forces that will now re-shape it – render physical architecture impossible, at least in any meaningful form. While École’s image is a projection, showing an imagined future as if it existed, it also freezes a transitory moment, for the Cathedral’s surroundings will surely be altered beyond all recognition as they are re-built. École’s proposal in all its deliberate indeterminacy offers the only possibility of stability, one that is barely possible as architecture but highly suggestive as imagery.

Combining site photography with self-effacing architecture, such digital collages resist architecture’s positivistic and instantiating claims, so readily accepted by photo-realistic renderings. They act negatively by blotting out aspects of the familiar and present landscape with fictive rather than factual alterity. In so doing, these images acknowledge architecture’s repeated failures as a techno-functional machine for amelioration while still honouring its potential to conjure a better world. By reducing itself to nearly nothing, the architecture in these images becomes defined by its nonappearance. In creating a void both within its external context and its internal content, architecture performs an act of self-denial.

It is crucial that these self-effacing architectures not be understood as negations, nor as refusals of architecture’s world-making powers. Just as the appearance of the colour white on pixelated screens is in fact the co-presence of all other colours, what results from these ‘blank’ architectures is a space of iterative possibility from which an infinite field of as-yet undefined futures may emerge. Conceived in the imagistic world of digital software and printed architectural publications, such images confirm the openness inherent in so-called ‘paper’ architectures. While certain representations may be understood as terminations, reducing architectures to single statuses (this is the case with ‘as-built’ construction drawings), at their most potent, images amplify architecture’s iterative power through their open-endedness, holding out multiple potentialities for future instantiations.

This is by no means confined to the world of image-making or paper architecture. As evinced by ‘Seven Rooms,’ Office Kersten Geers David Van Severen’s 2010 installation at the Venice Biennale, this space of iterative possibility – created by the addition of a porch of white steel mesh – also instantiates itself in real objects. In the absence of a definite image, Office’s transformation of an old brick storehouse in the Arsenale’s garden offers itself completely to the display of images, including photographs of ruins and anonymous buildings by Bas Princen and perspectives of unbuilt works by Office. [2] What is created by Office’s installation is not a lack of representation, but rather its boundless possibility.

As these examples confirm, architecture has always relied on images to reach its full potential. By not fixing a definite image, architecture’s disciplinary agency is paradoxically increased when it opens itself up to its full iterative faculty. Whether built or unbuilt, architecture’s power is amplified by multiple iterations, both conscious and unconscious, image and object, which it inevitably brings into circulation. The single material presence of a building is not endangered by the mass of representations – sometimes including other buildings – produced in the course of its conception, construction, and dissemination. Rather, it is through such iterations, each with its own degree of materiality, that architecture achieves its fullest possible affect.

Excerpted from Peter Sealy, ‘The Image as Iteration,’ in Iteration: Episodes in the Mediation of Art and Architecture, ed. by Robin Schuldenfrei (Oxon: Routledge, 2020), pp. 154–175.

Several of the contributors to Iteration, including Peter Sealy, participated in a Research Forum evening at the Courtauld in February 2021. Watch the recording of the event here.

Notes

- Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron and Remy Zaugg, ‘The Tiergarten as Geometric Centre,’ Architectural Design, no. 92 (1991): 55.

- Moritz Kung and Enrique Walker, Office Kersten Geers David Van Severen – Seven Rooms (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2009).

From the Drawing Matter Collection: two urban insertions

– Julian Lewis