John Hejduk: Means, Ends

Peter Eisenman was wrong… It is architecture, even if you can’t ‘get in it.’[1] But he was also right… ‘The tradition of the architect-writer is well precedented in the history of architecture.’[2] It might remain a question without an answer, though it is curious that on large, the once hyphenated role of ‘architect-writer’ has lost its binding punctuation mark, becoming instead ‘architect, writer’ or even just ‘architect’. It could be that implicit in the title ‘architect’ is also ‘writer’ (along with the numerous other hats worn by those in the discipline), so the omission was simply an act of economising means. Or, more pessimistically, maybe most architects simply forgot how to write.

Drawing and writing in the architecture of John Hejduk are two acts in constant dialogue. His work projects narratives as much as it does forms, sustaining the tradition of the architect-writer. And within his prolific body of work, the Masque may fairly be considered the clearest expression of this dialogue, constituting a rich assemblage of images, texts and buildings into archipelagic wholes. The Masque is a conspicuously intertextual work, but it is also an intratextual one: that is, it engages in an embodied self-dialogue, a self-questioning.[3] In fact, it is this inter- andintratextuality that lends the beginning and ending of each Masque its ambiguity. To separate one from the next is a difficult and even erroneous task. And so, it would make sense for the representation of such a work to engage in a degree of self-reflectivity too. Hejduk’s axonometric-plan does this.

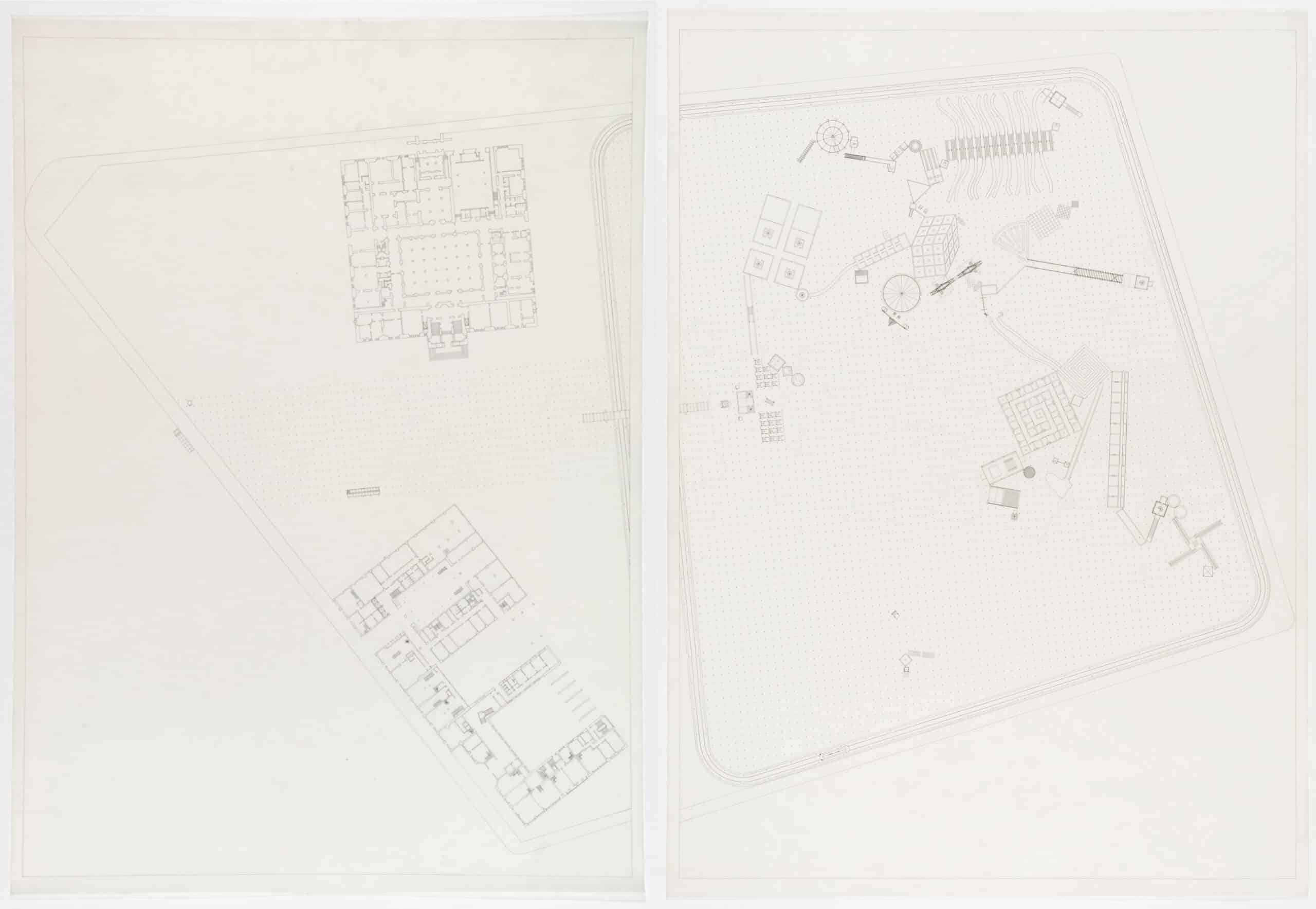

The fold-out site plan that marks the beginning of Hejduk’s 1986 publication, Victims Text 1, is a rich and layered drawing. It depicts two existing structures on the Berlin site, and Hejduk’s archipelago of sixty-seven characters, separated by a double-walled hedge. A dotted grid mediates the two sides of these two hedges, notating a planting scheme of evergreen saplings. On one level, the very act of folding out the roughly A3-sized page requires a literal turning over of a new leaf, speaking to the new life projected by Hejduk on the former site of the Gestapo Headquarters. On another level, the polygonal site extent touches the inscribed page border in a tangential manner, mirroring the type of connection Hejduk prescribes between the proposed structures within the hedged portion of the site. And on yet another level, the drawing, depicting some elements cut at the ground plane and others in planar projection, also contains an anomalous, axonometric projection in the centre of the archipelagic mass. In fact, this element’s plan is axonometric.

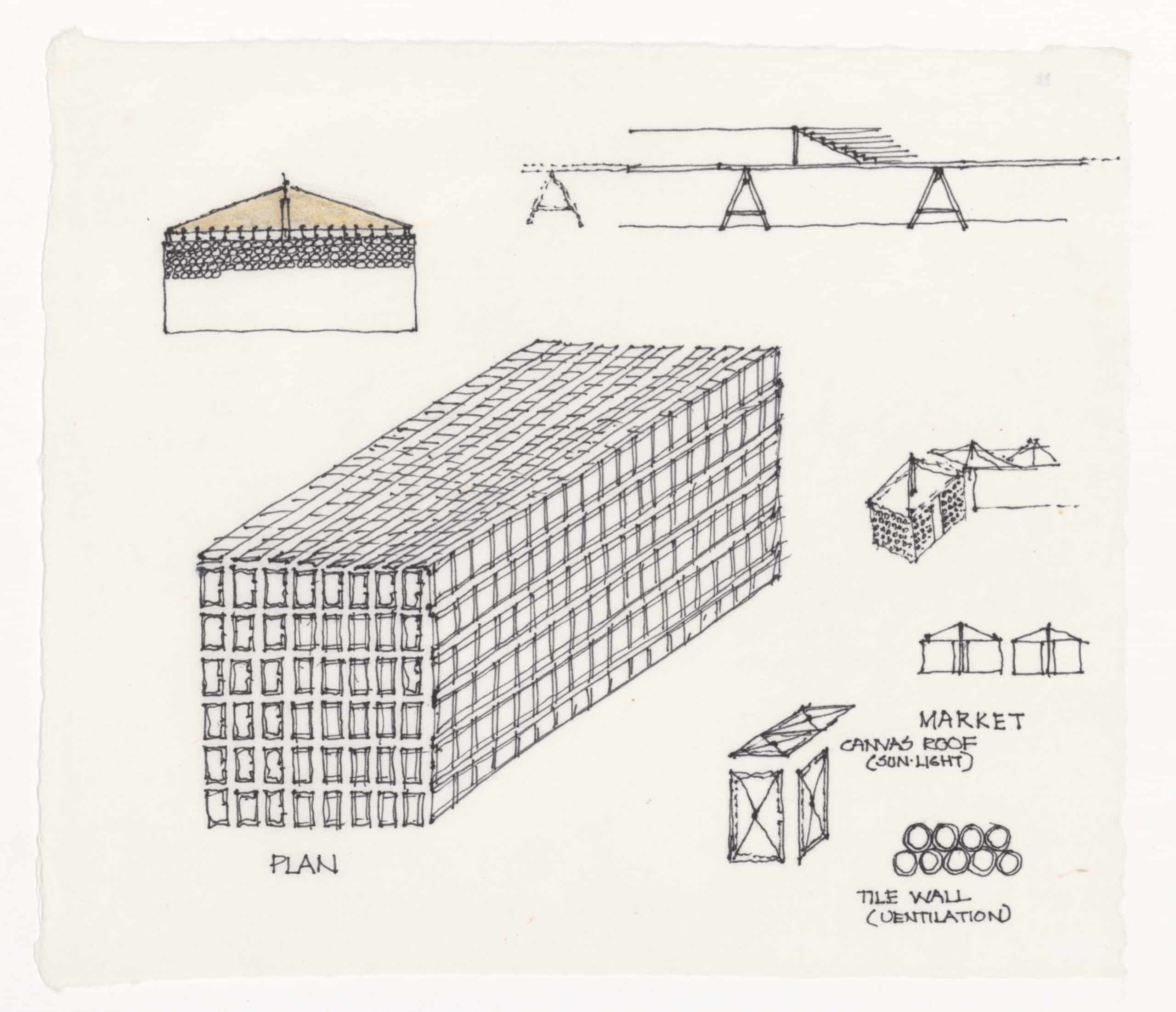

Given the inter- and intratextuality of the Masque, it is unsurprising that Hejduk actually explored the possibility of an axonometric-plan years earlier, in The Lancaster/Hanover Masque. A drawing produced for its 32nd character, Market/Merchant, similarly depicts what looks to be an axonometric projection of a rectangular, extruded form, though Hejduk writes below it (in no uncertain terms) ‘PLAN’. In the drawing’s corresponding note, Hejduk writes that the isometric plan ‘came from his interest in the problem of foreshortening’, referring not to himself, but to the fictional Merchant. It may fairly be considered a narration of Hejduk’s own interest as well though, given his numerous studies into projection through the pre-Masque projects. Speculation aside, what Hejduk’s axonometric-plan is doing in an immediate sense, is conceptualising the notation of the project. Through this act, the notation becomes the project. In his essay The Flatness of Depth, published in Mask of Medusa, Hejduk writes:

Although the perspective is the most heightened illusion—whereas the representation of a plan may be considered the closest to reality—if we consider it as substantively notational, the so-called reality of built architecture can only come into being through a notational system. In any case, drawing on a piece of paper is an architectural reality.[4]

Here, Hejduk negates the possibility for the texts of architecture to be separated from the ‘so-called’ realities they describe. When faced with the Masque, we simultaneously look and read, calling to mind the text-images of American artist Duane Michals (who in the second half of the 20th century broke the rules and began writing on his photographic prints). Sometimes a paragraph is written and other times just a sentence, though in both cases, the work becomes fundamentally unclassifiable; the micro-inseparability of one medium from the next mirrors the macro-inseparability of one project from the next. As far as the Masque is concerned, the drawing is the architecture, as is the text, as is the photograph, as is the building. Not merely an instruction (as it is often regarded), but an architectural reality in its own right.

Its means are its ends, frustrating the discipline.

Notes

- John Hejduk and David Shapiro, John Hejduk: Builder of Worlds, DVD, directed by Michael Blackwood, Michael Blackwood Productions, 1992, 00:19:00. [Here, John Hejduk recounts an interaction between himself and Peter Eisenman, concerning a Berlin exhibition hosting House of the Painter and House of the Musician.]

- Peter Eisenman, ‘Editor’s Preface’ in Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City, trans. by Diane Ghirardo and Joan Ockman (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1984), 1.

- K. Michael Hays, ‘Hejduk’s Chronotope: An Introduction’ in Hejduk’s Chronotope (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 9.

- John Hejduk, ‘The Flatness of Depth’, in Mask of Medusa (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1985), 313.

Anton Bucich is an architect-writer currently based in Ticino, Switzerland. The above text is a fragment from his 2024/25 Elaborato Teorico titled This Book is an Architectural Project Architecture, written under the supervision of Professor Enrique Walker at the Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio.

– Ray Lucas