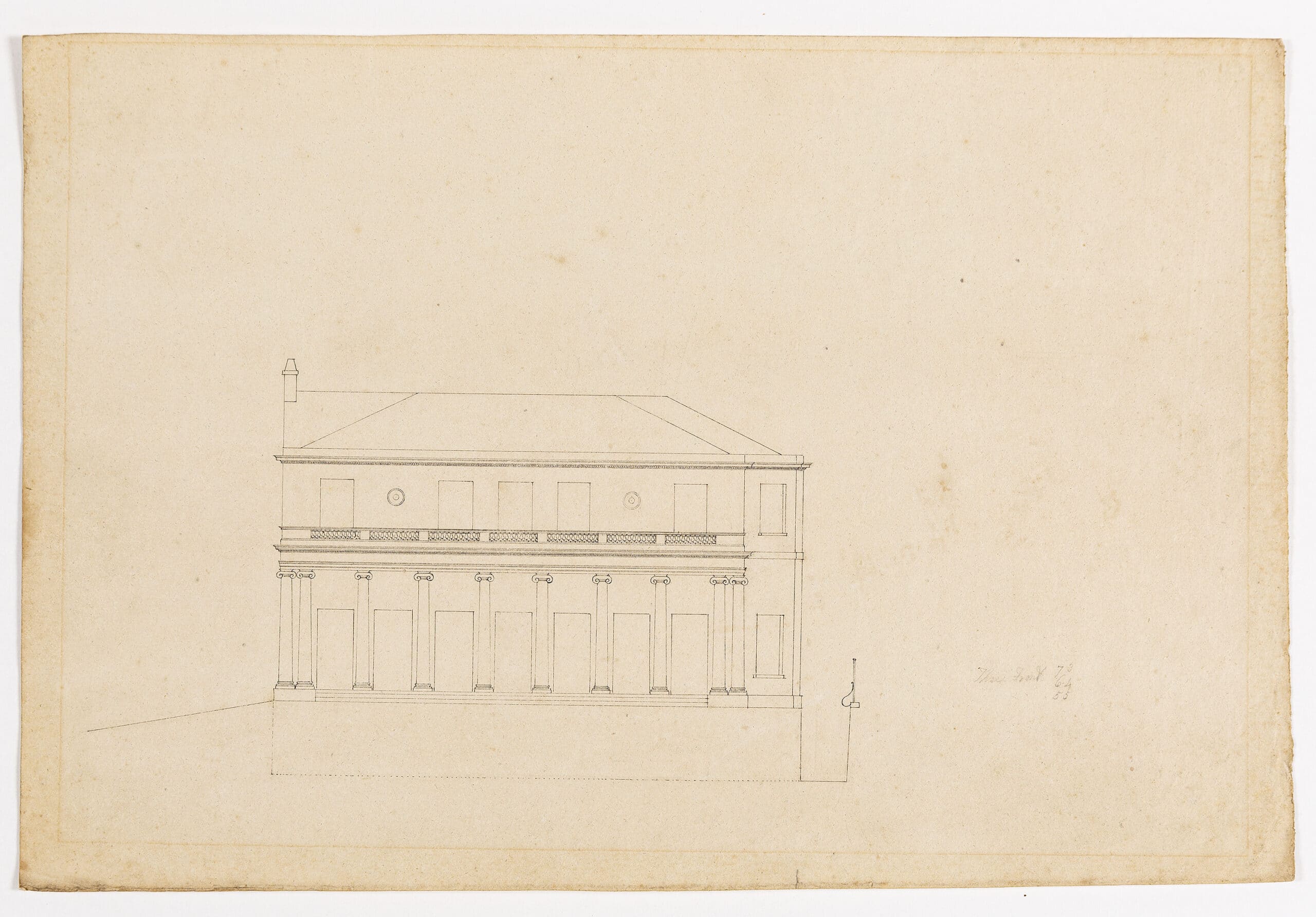

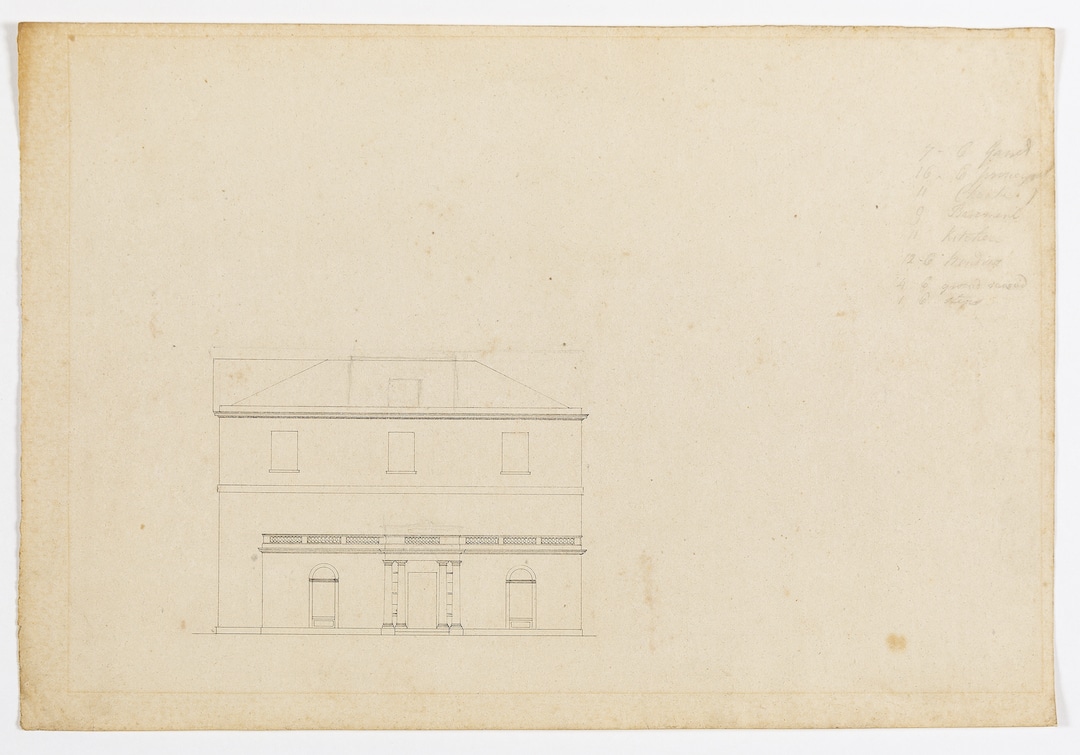

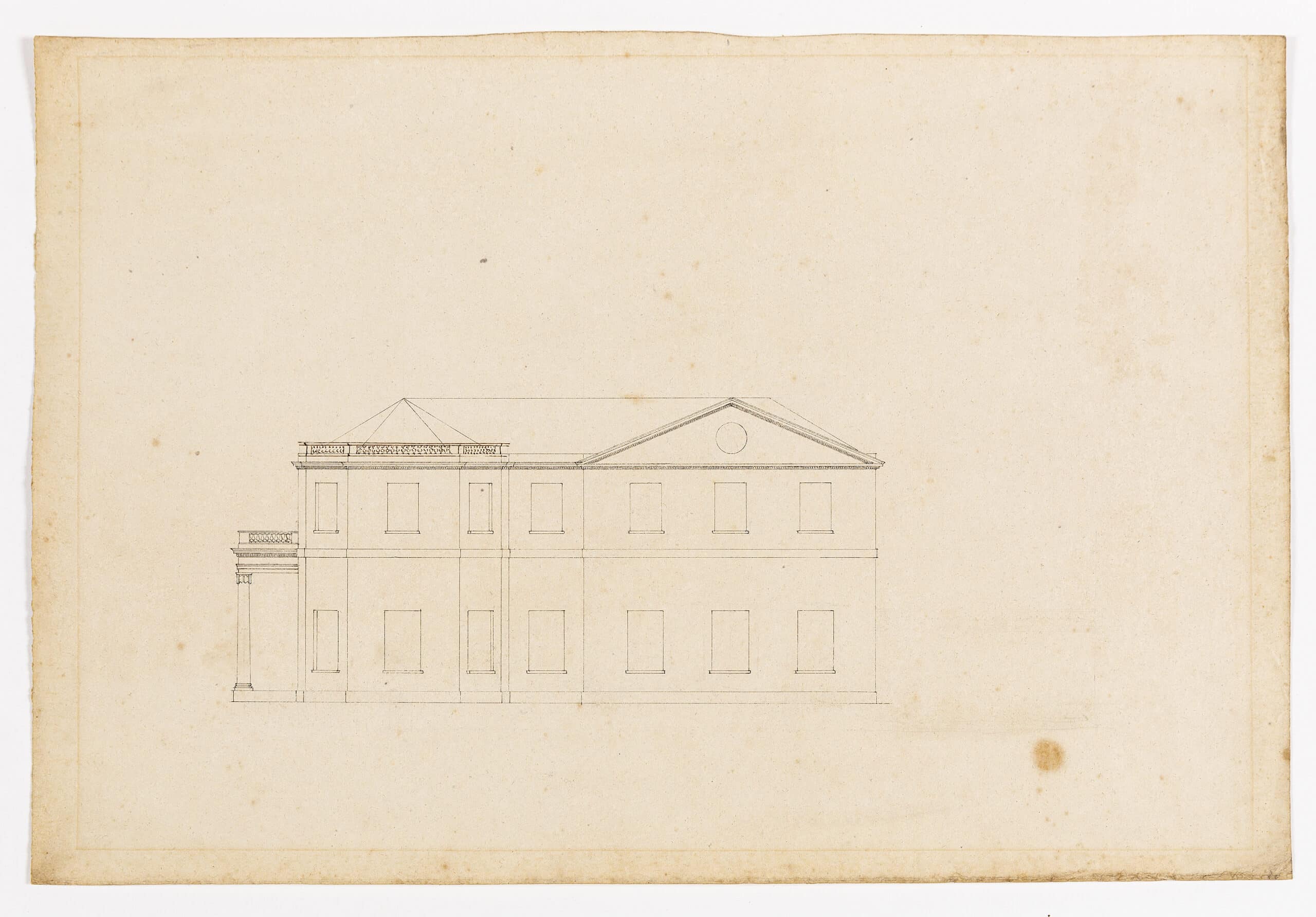

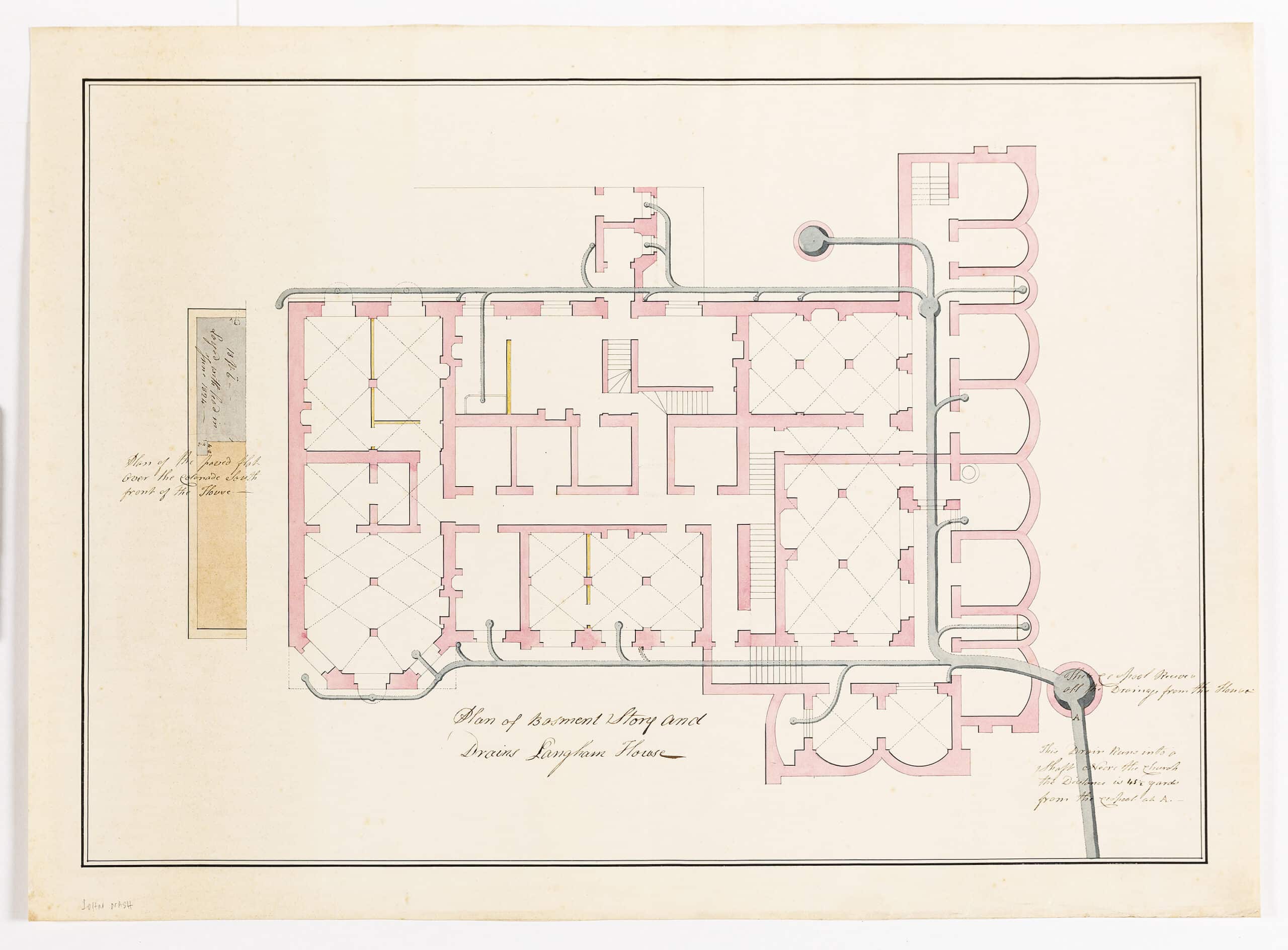

John Nash: Designs for Langham House, ca. 1812–1816

Extracted from Stories from Architecture: Behind the Lines at Drawing Matter by Philippa Lewis, published by MIT Press © 2021. Preorder the book here.

The drawings around which Stories from Architecture are written are all part of the Drawing Matter collection. Some of the texts were first published as ‘Behind the Lines’.

Nash looked back on what he regarded as one of his most successful coups. For the last few years he had been working tirelessly on a plan to create a new street connecting Westminster with the fashionable new terraces and squares that were spreading northwards, ever closer to the farmland on Marylebone Fields that he wanted to develop. A few years previously Nash had seized the opportunity to make his plan more plausible with a cunning manoeuvre: letting that spendthrift Lord Foley off the £70,000 he was owed for work on his country house, Witley Court, in exchange for Foley House and its thirty or so acres.

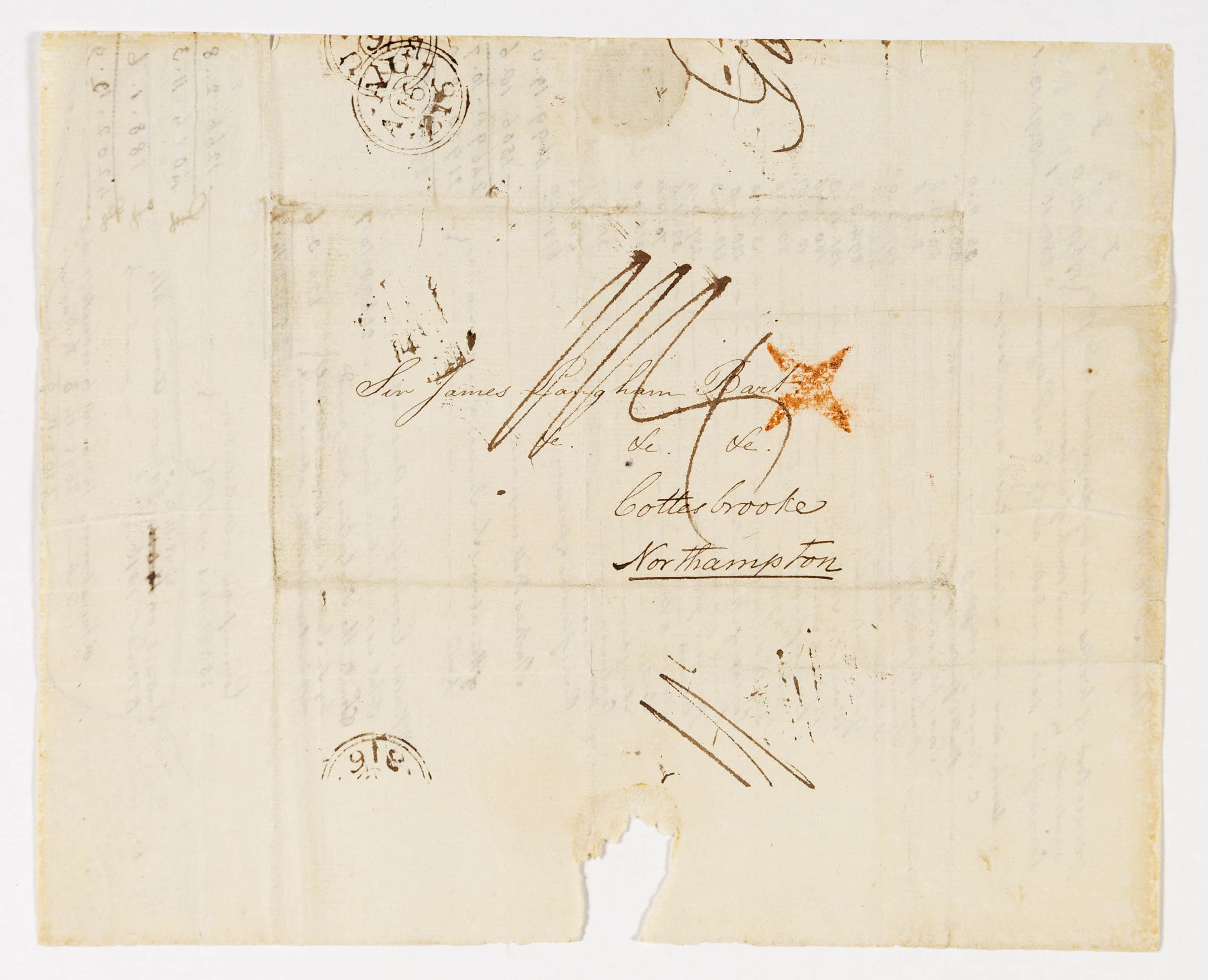

Before he began writing, John Nash took stock of his situation. The deal he’d made with Langham had initially looked promising, but now the man was haranguing him with a galling list of moans – about damp, drains, stinks, and soot – and demanding answers. Sir James Langham was undeniably a man of substance. For one thing, the recent and unexpected death of his nephew at the age of sixteen had landed him with the baronetcy and the inheritance of Cottesbrooke, a substantial estate in Northamptonshire. In addition to being the Member of Parliament for St. Germans in Cornwall, he was also, more significantly, married to Elizabeth Burdett, daughter of that noisy reformer Sir Francis Burdett and granddaughter of Thomas Coutts, a fount, reckoned Nash, of almost limitless wealth. Langham had wanted an elegant new town house, and Nash had a prime site to sell.

Foley House had blocked the southern end of Portland Place, jeopardising the route that Nash had devised. Nash’s purchase gave him control. He quickly sold land for the new road to the Crown, opening a way for it to run uninterrupted up from the Prince Regent’s Carlton House to Marylebone. He then neatly tied up the loose ends of the deal by selling the remaining land to Sir James Langham with the proviso that he, Nash, must be the architect of the building that would rise in place of the demolished Foley House.

Nash, feeling a martyr to his work but never wishing to be anything else, wrote his response speedily, systematically answering each of Sir James’s complaints about the newly completed Langham House. Damn the man, didn’t he have more pressing country matters to think about – poor parishioners, almshouses, tenants’ cottages? It was a hot Friday in August and Nash cursed that he himself was not in the country, in his gothic library at East Cowes Castle, enjoying the prospect of the distant sea beyond shady woods and looking forward to a genial evening of cards with his friends.

Dover Street, August 16th, 1816

Dear Sir James,

I went to your House yesterday with Mr. Repton and my executive man in the office and examined every part of the building from the bottom. The cracks in the plastering are from the shrinking of the timbers which cannot be avoided but as the timber has shrunk as much as it is likely to do – there will not in all probability be any more cracks.

I have taken up the skirting and one of the boards in the long chamber passage and find that the sound boarding is properly done but, as I apprehended, the clerk of the works omitted plastering the walls behind the cove, considering it as an expense thrown away… Webb insists that I told him to omit that plastering – it is possible I may have done so (though I do not recollect it)…

Nash paused briefly and impatiently. How in God’s name was he supposed to remember such a trifling detail while being involved with so many other projects? The Prince Regent was pressing him to produce schemes for the Music and Banqueting Rooms in Brighton and some alterations to Carlton House; there were problems with the canal in Marylebone Park; and he needed to consider the new street facades leading up to Oxford Street.

… for I should have thought the sound boarding sufficient – it is my intention to take the floor up over the Eating Room and try to cure where you aver the evil is greatest, if not over the Library, but during your present absence I do not mean to do more for I should wish to cure this first that you may not be put to unnecessary expense.

Nash hoped that a mention of saving money might persuade Langham to stop pestering him about how he couldn’t eat in peace without hearing servants and children in the bedrooms above, let alone think in the Library. It was possible the builders had skimped on pugging the sound boards. He always specified about an inch and a half of mortar and chopped hay – that usually sufficed.

If you remember I told you that the woodwork would shrink and that in two or three years you would have to refit it – this is always the case, and an advantage will arise from taking up the floors as they will be relaid close and in all probability shrink no more and the skirtings keep close to the boards which have no shrinking. When the boards are up it is my intention to use other means to address the sound.

Perhaps George Repton would come up with an idea for… ‘other means’. Nash liked George; he had proved himself to be dependable and loyal even after all those shenanigans with his father and brother. He thought about poor George’s recent confession that he was being driven to distraction by his love for Lady Elizabeth Scott, whose father was implacably opposed to their marriage. He personally had always found work to be a cure for emotional upset; he hoped George would too. Returning to his letter, he continued:

I have found every part of the work perfectly strong without any settlement except in the long chamber partition and the partition by the side of the attic stair – to there I mean to add additional braces that they may not settle any more.

Nash felt most aggrieved that Langham was insinuating the house was unsafe – ludicrous man. Next thing, he would be employing another architect.

I find the flutes in the pannels [sic] of the doors are not composed as we supposed [with] best wood and have shrunk from the glue by the moisture of the brick walls, this will be put to rights and can happen no more and the little rosettes in the mahogany are done in the best manner though two or three of them by hard rubbing came out but we shall guard against that also in future.

Tomorrow I shall get a chimney sweeper to go up every flue in order to ascertain the cause of the soot falling – which is certainly not owing to the construction of the flues – and inconvenient as it is that soot should fall, it is infinitely safer than that it should settle and accumulate – I hope to be able to send you an account of this defect in a few days.

At this point Nash reflected that, however much he liked designing an interesting picturesque cottage chimney, chimneys in townhouses were very dull. He certainly hadn’t the patience to investigate flues. Did he have to explain about the danger of chimney fires?

I understand from Repton that you do not like the appearance of the door in the gallery, wanting architraves. I shall therefore – unless you write to the contrary – order them, though there is no necessity for them, the edges of the plastering in every situation are liable to injury – but not more so round those doors than any other external angle. There is no damp in the waterclosets, but the stone floor which is lying on the ground will always stain the stones more or less. If you were to put deal floorboards on the stone leaving an inch space between the stone and the boards – the appearance of damp (and it is nothing but appearance) will be done away.

Nash’s irritation buzzed. Why were clients so obsessed with this? There could hardly be a building in the whole of England that wasn’t damp, let alone one on London clay. He knew it was untrue to say you could only have an appearance of damp – if it looked damp, then it was damp – but the floorboards would probably keep it at bay for a while.

In the stables I perceive that Webb has not taken out the bearers of the manger, which runs into the wall. I have ordered that to be done and another coat of cement along the wall under the manger. It may assist to keep out the smell of the stables from the Hall. The Drains I have not yet examined.

‘Nor have I any intention of examining them’, Nash thought. Repton could look at them sometime next week. Langham knew perfectly well – or at least he should have done, since he was one of the commissioners – that the sewer specified in the New Street Act had been approved by both Rennie and Telford. His drains would flow free as air. Foley House had to put up with the choked old Hartshorn Lane sewer.

Langham’s anxieties dismissed Nash moved on to the more important subject of money.

I was not aware of your going into Northamptonshire or would have attended you in settling the accounts. I have accompanied the bills with the receipts and they are right on the other side is a statement of our accounts. Slack will take a bill at your own time and I will do the same for £2,000, but if you could favour me with a cheque or a bill at two instalment dates for £500 now, you will oblige me very much.

On recollection I leave a blank for the summation in case it should be inconvenient to advance so large a sum and can settle the other bills when you come to town in September and at that time rectify any errors you may find with the accounts.

Scanning quickly over the scraps of paper on which he had written the accounts, Nash reckoned they looked approximately correct.

I have the honour to be,

Dear Sir James, your faithful servant John Nash

Sir James Langham read John Nash’s letter. He was enraged. ‘Your faithful servant, indeed! Nash can go to blazes! I can’t abide the man. Face like a monkey, typical untrustworthy Welshman. He is neither faithful, nor a servant, but an insolent architect, and one I would not willingly have chosen. Apart from the stink in the hall emanating from the stables and a minimal bit of bracing, he appears to deny every single problem I’ve raised – or hasn’t even begun to address them. Why, pray, has he not looked into the drains when I explicitly pointed out that they are seriously at fault? I have told him several times I cannot have my family live there, risking their health, while the miasma from the drains is so noxious. Nash’s toadying to the Prince Regent and his ridiculous buildings prevent him from properly carrying out my commission. What a tragedy it is that we are ruled by that Colossus of Venality and his set of degenerate reprobates. There is no limit to his desires or restraint to his wanton profligacy. He demoralises the country’.

Langham immediately resolved to have nothing more to do with Nash. Was old Thomas Leverton still alive? There was an upright man with a fine reputation. Perhaps he could be invited to call at Langham House in early September when he was back in town.

Notes

John Nash (1752–1835) began working in London as a speculative architect and builder in the 1770s, but was declared bankrupt and retired to Wales, where he mainly built country houses. He returned to London in 1796, and in 1806 was appointed architect to the Department of Woods and Forest, for whom he designed a plan for Regent’s Park. In 1813 he became Surveyor General and worked principally for the Prince Regent. From about 1795 Nash collaborated closely with the landscape gardener Humphry Repton, and two of Repton’s sons, John Adey and George, worked in Nash’s office.

Nash was divorced from his first wife, Jane, in 1787 and in 1798 married twenty-five-year-old Mary Ann Bradley. John Rennie (1761–1821) and Thomas Telford (1757–1834) were the most celebrated engineers of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The new road was originally planned to run south from Portland Place: Langham House was built in line with the west side. However, a difficulty with the houses in Cavendish Square meant it became necessary to deflect the street eastward to form a bend (on which Nash later built the church of All Souls, Langham Place). At this point Nash exacted his revenge on James Langham by proposing a new terrace of houses whose rear elevations would butt up against Langham House’s façade. The only course open to Langham was to buy from Nash the land destined for the new housing. Nash seized the moment to charge an eye-watering price.

The Langham family kept the house until 1833, after which it was acquired by the Countess of Mansfield. Her family sold it in 1860. Langham House was demolished to make way for the Langham Hotel, the grandest hotel in London at the time of its opening in 1865. Thomas Leverton (1743–1824) was a successful architect of the period, credited with the design of Bedford Square in Bloomsbury. The letter from John Nash to Sir James Langham quoted here is in the Drawing Matter collection, DM 1712.8.6.