Leicester Engineering Building: Un-detailing

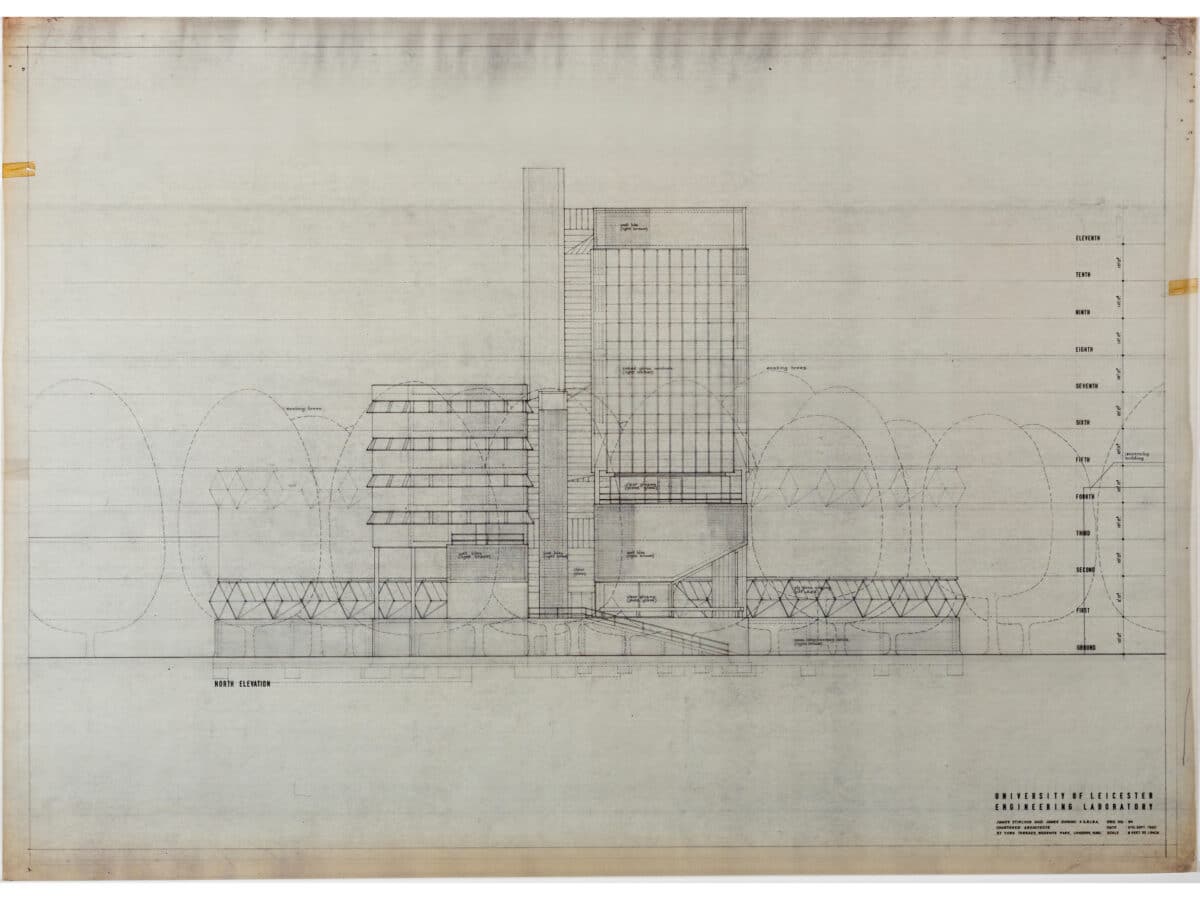

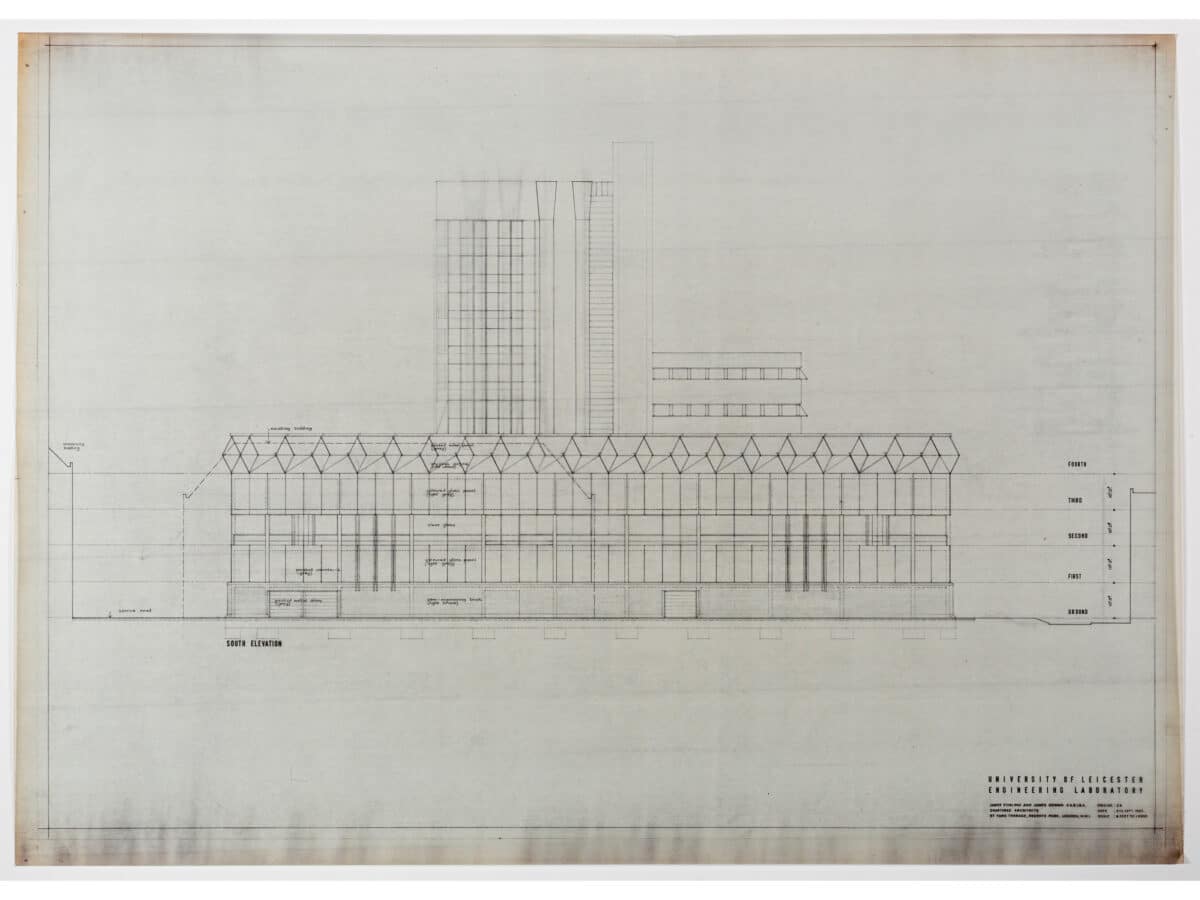

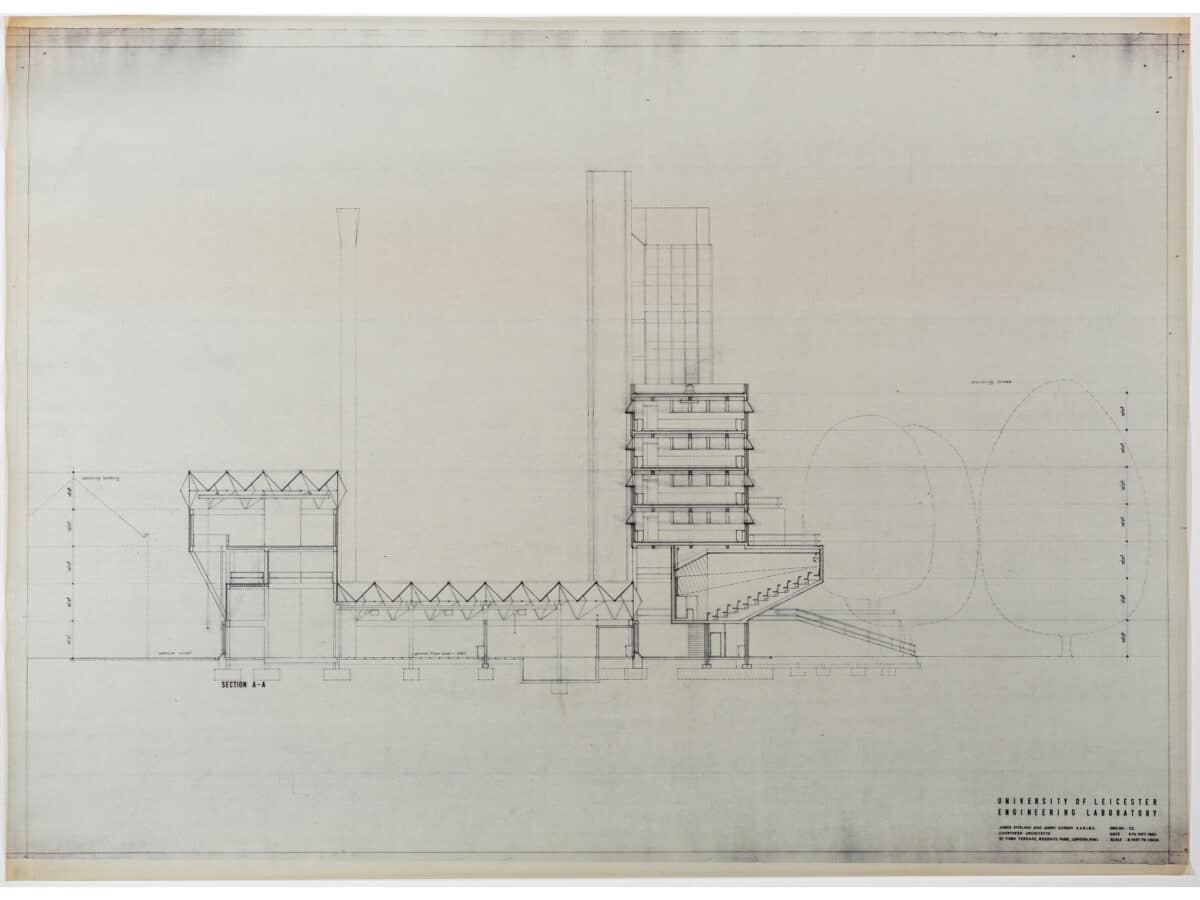

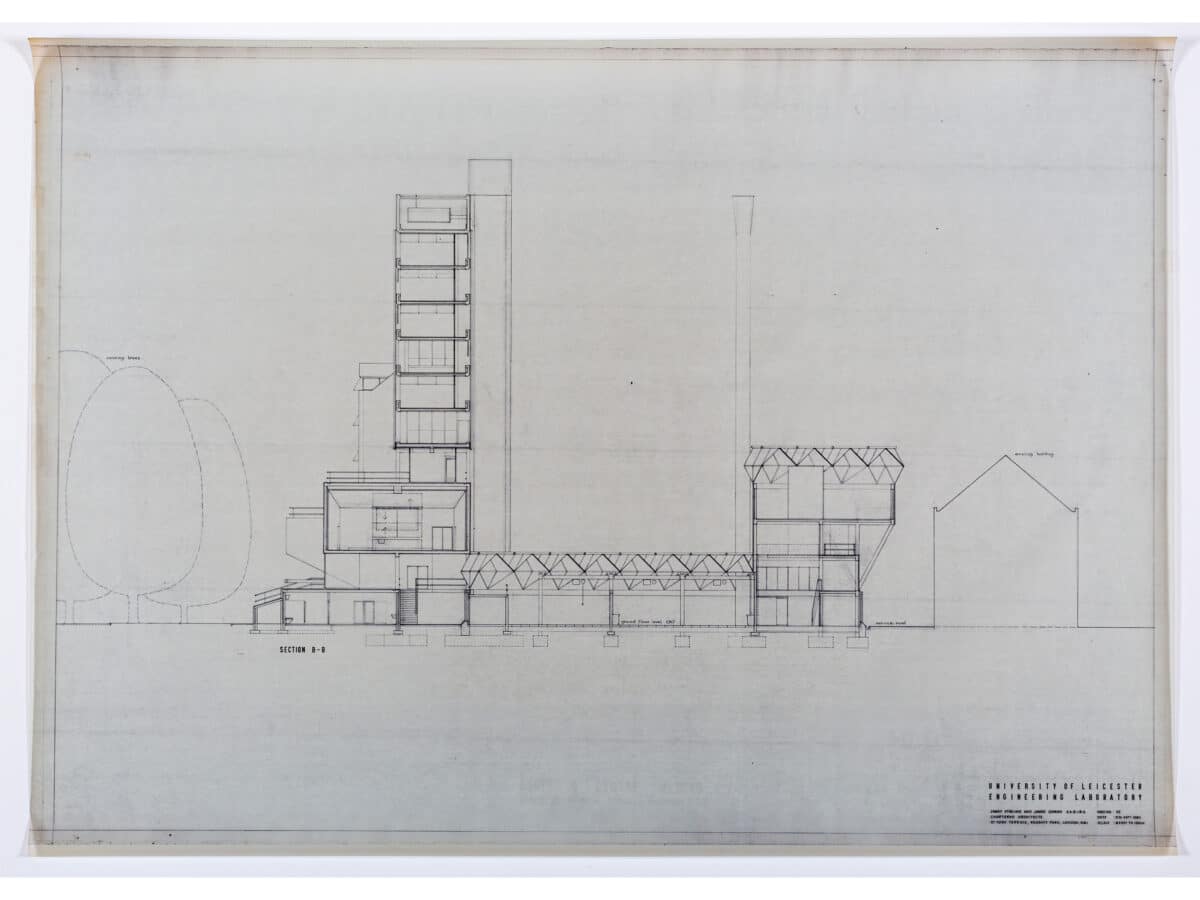

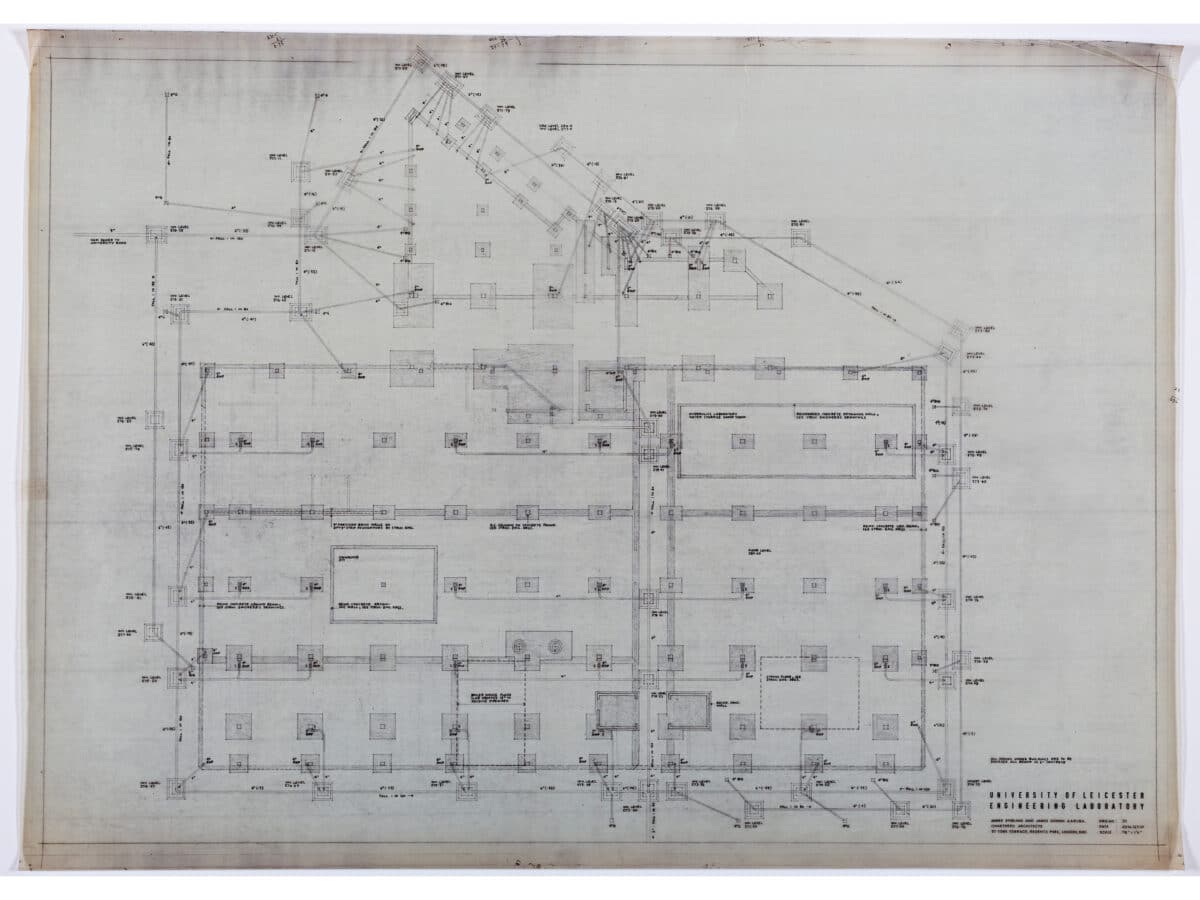

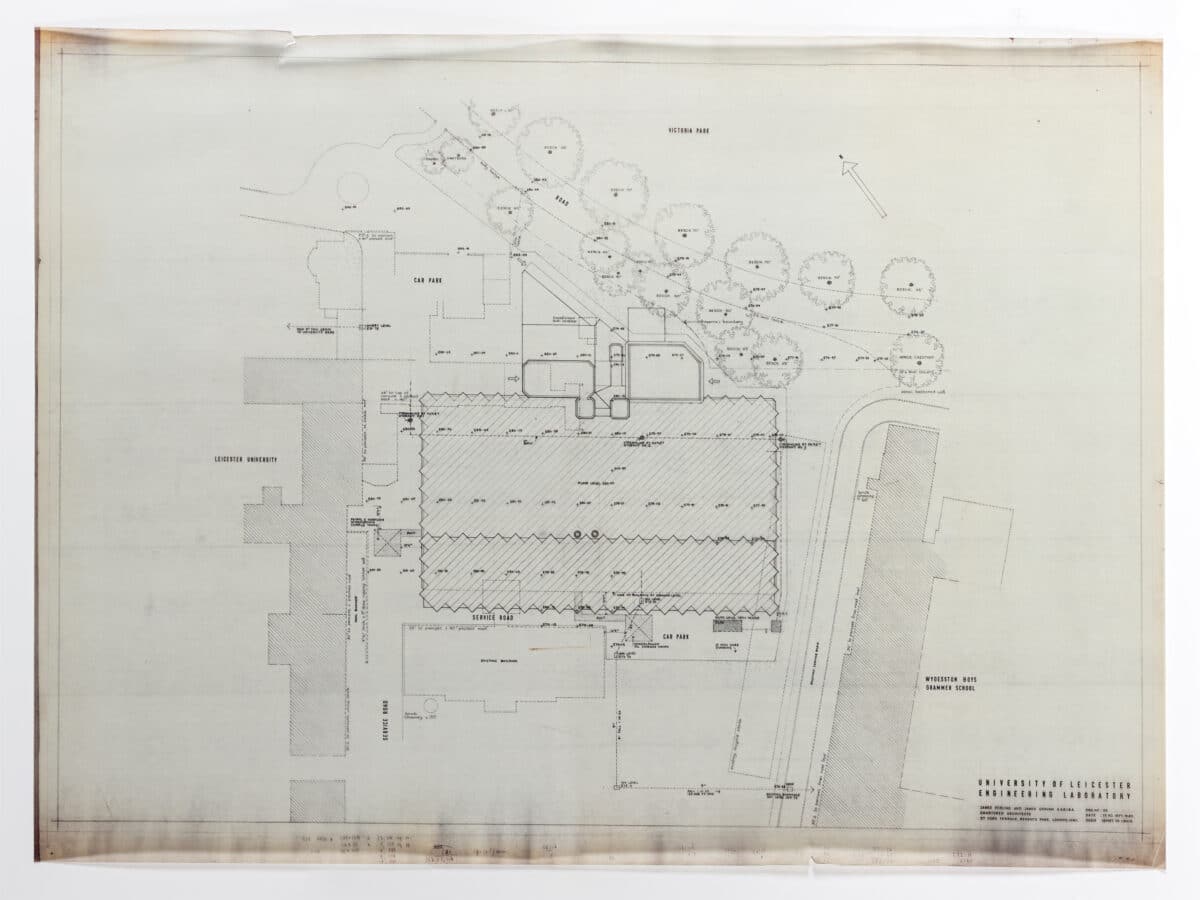

The building is in many ways as extraordinary as its details. At ground-floor level it confronts the visitor with a blank wall of hard-faced red brick, which is occasionally pierced with a rather private-looking doorway, except at the point where the glazed main-entrance lobby splits this defensive podium into two parts: one a rectangle enclosing the teaching labs, the other a moderately irregular polygon forming the base of two towers housing research and administrative offices. Over the heavy teaching labs there foams, like suds from some cubist detergent, a good head of angular north-light glazing, laid diagonally across the building. Down one side of the block, this pearly translucent glazing rises to four storeys, with the topmost floor of labs strutted well out over a service road that cannot, for the present, be eliminated: the whole complex has had to be crammed onto a site which, by common-sense standards, ought to be about 25 per cent too small for it.

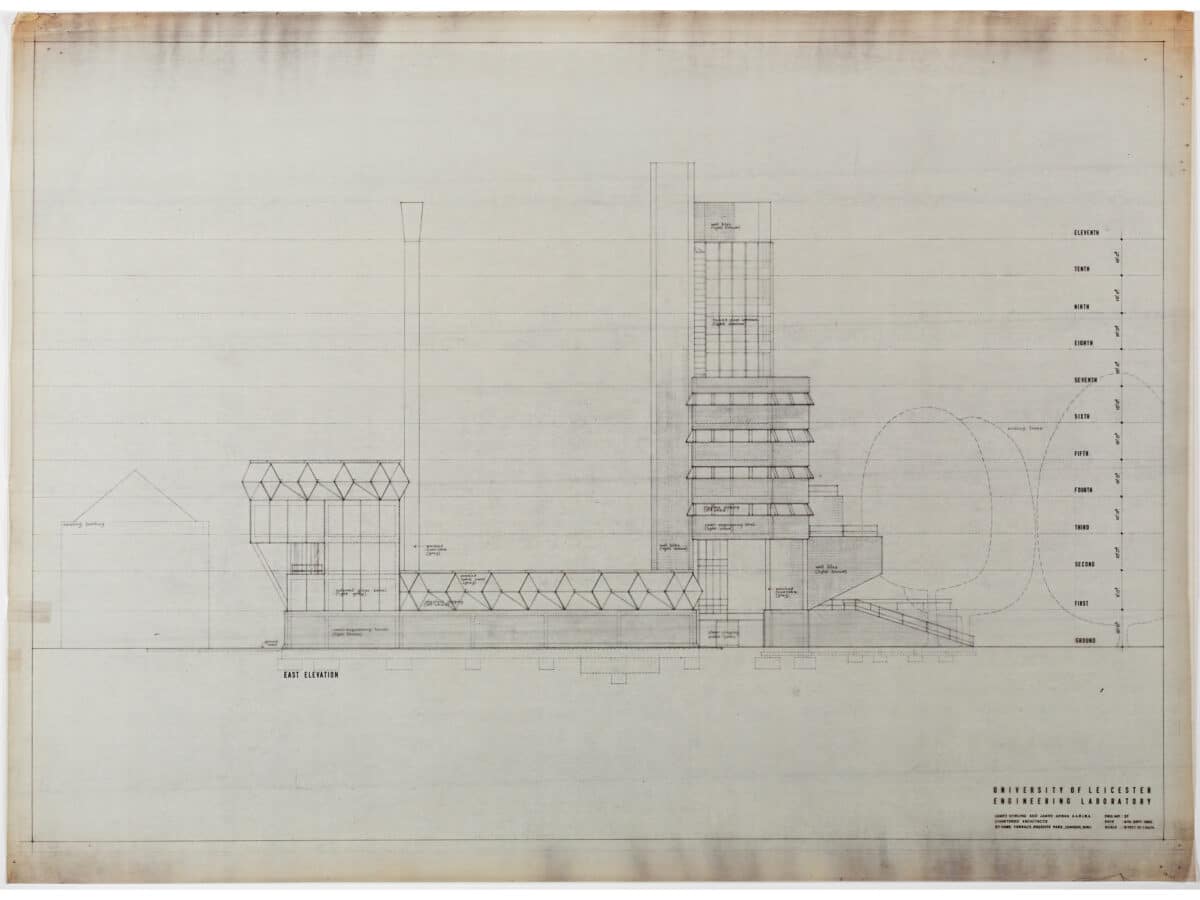

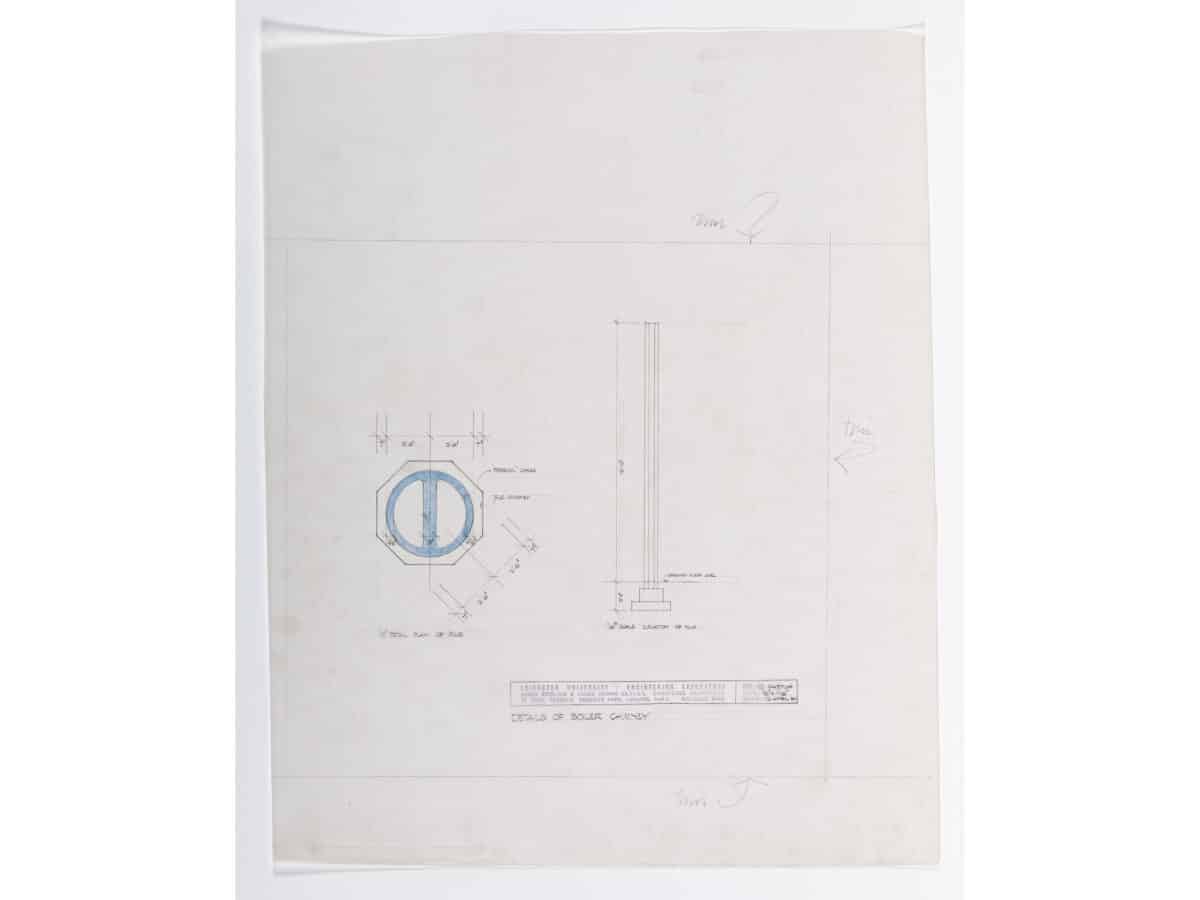

On the opposite flank of the main rectangle rise the towers, but they do not rise in any obvious or tidy-minded manner, since each rests on a lecture-hall that cantilevers out beyond the limits of the podium below. The research tower rises only five storeys above the smaller auditorium, and is relatively conventional in appearance, except that it has one corner snubbed off to clear a legal building line, and its bands of windows are in the form of inverted hoppers, the glass sloping out to shelter flat bands of ventilators underneath. The admin tower, which carries a water-tank on top to give the hydraulics labs at ground level sufficient head of water, has all four corners snubbed off when it finally reaches its typical plan-form and then rises clear above the research towers.

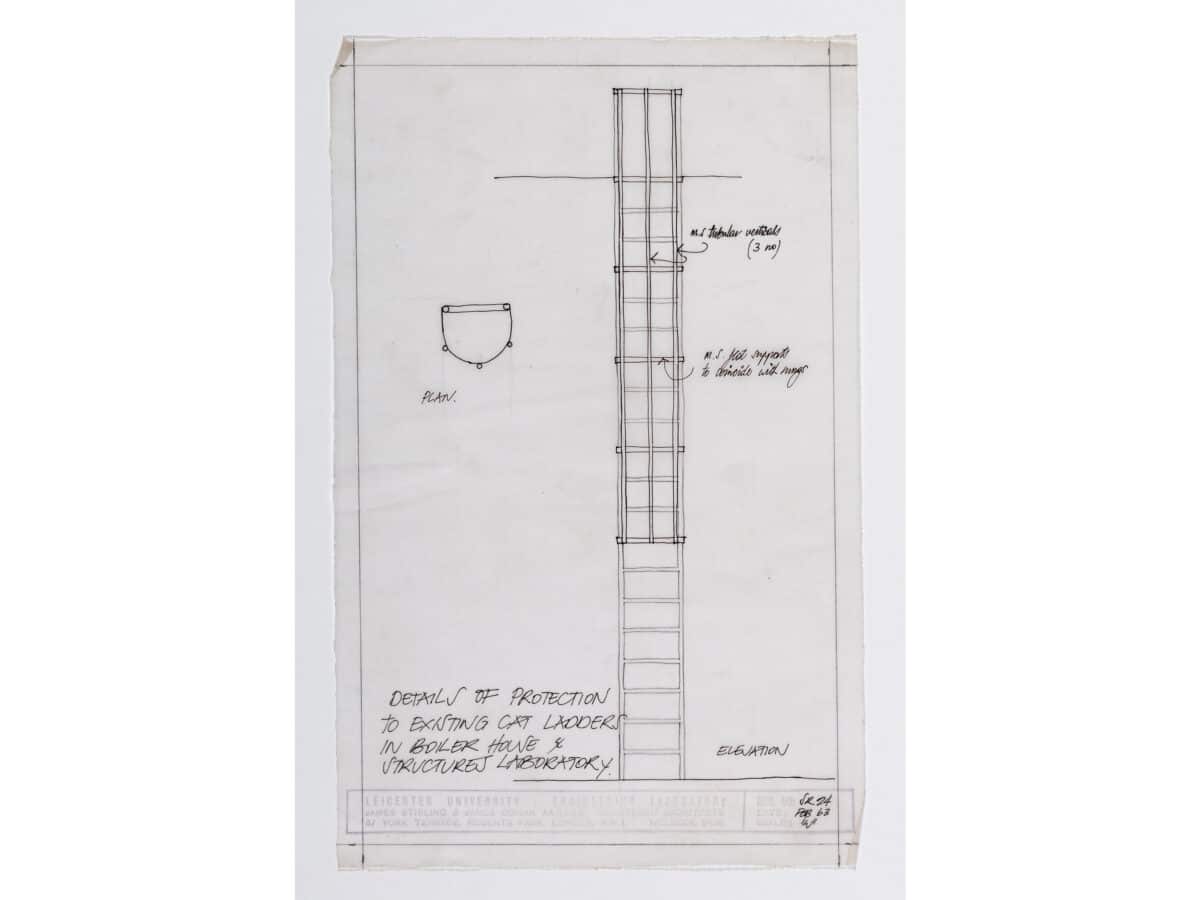

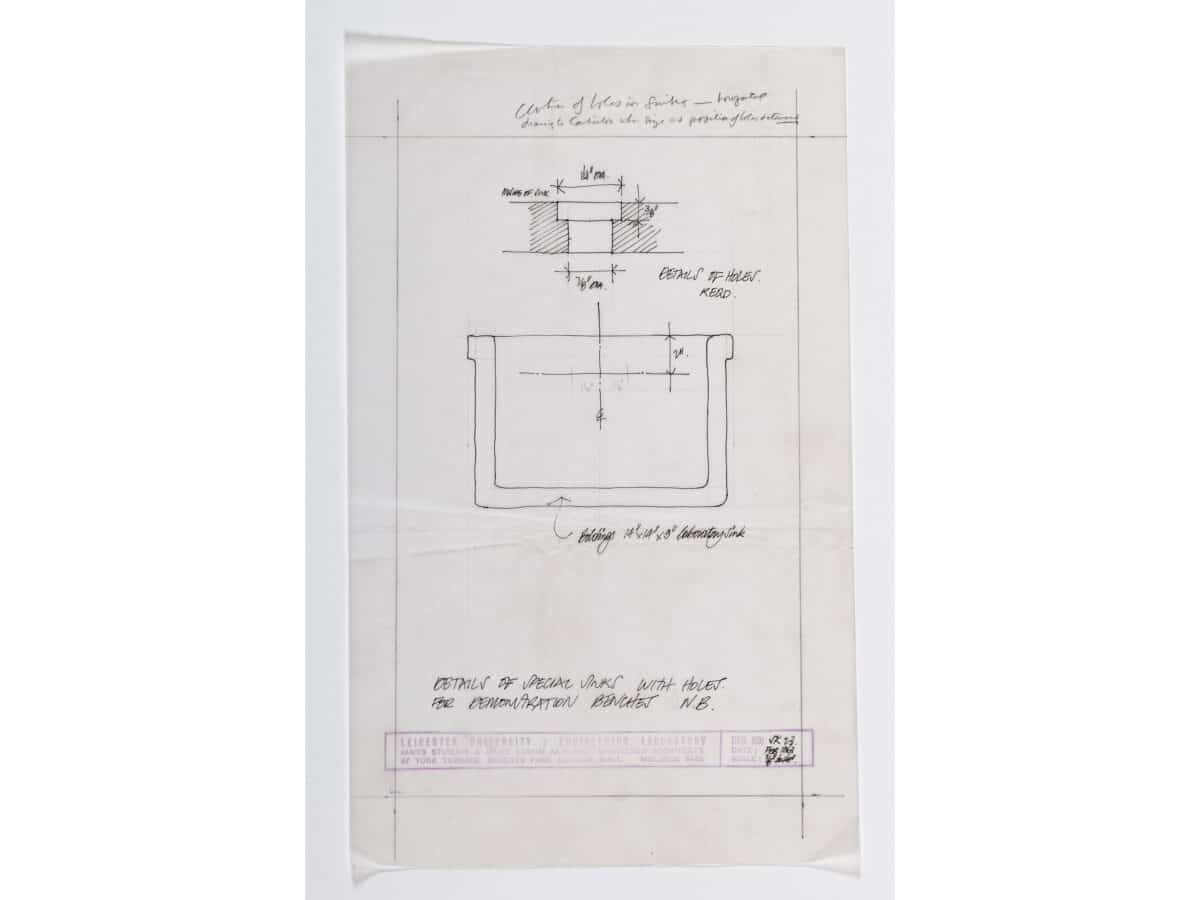

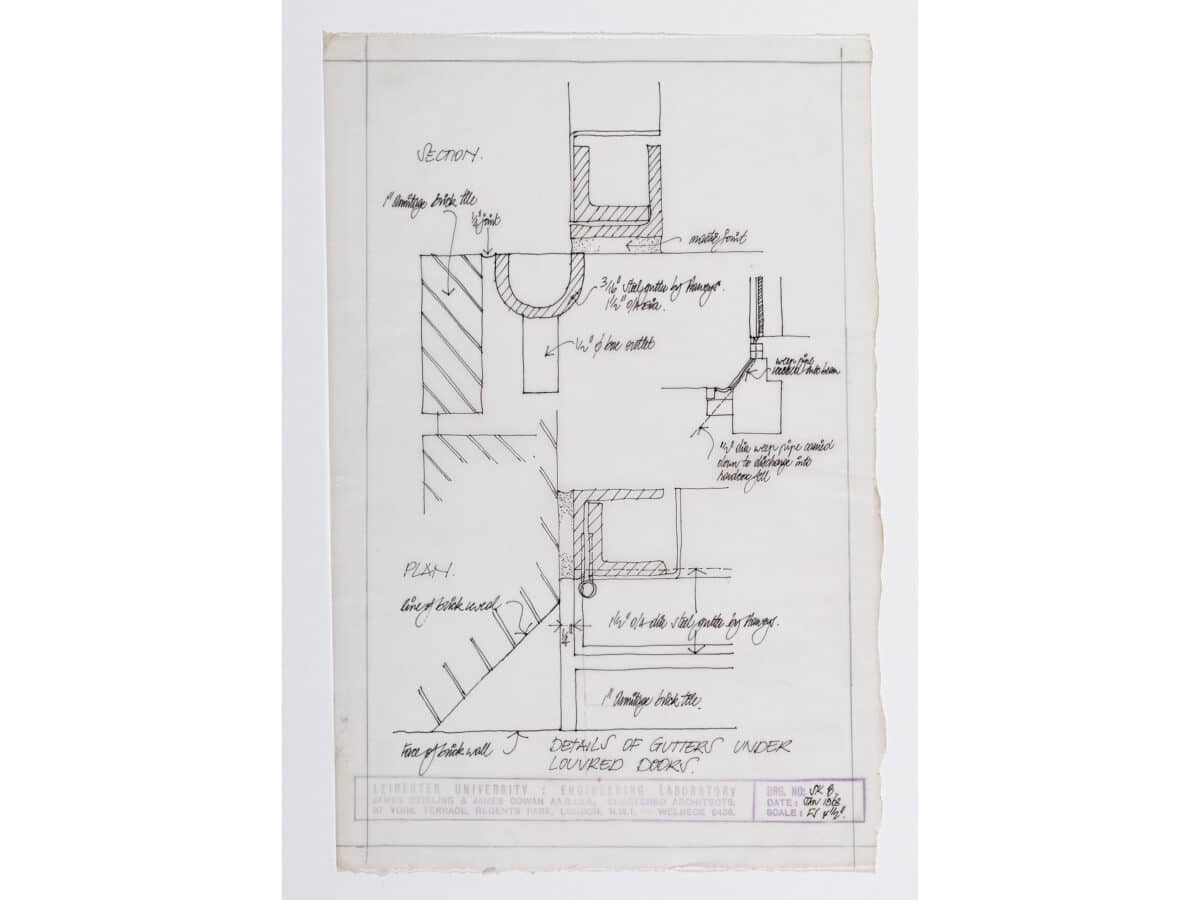

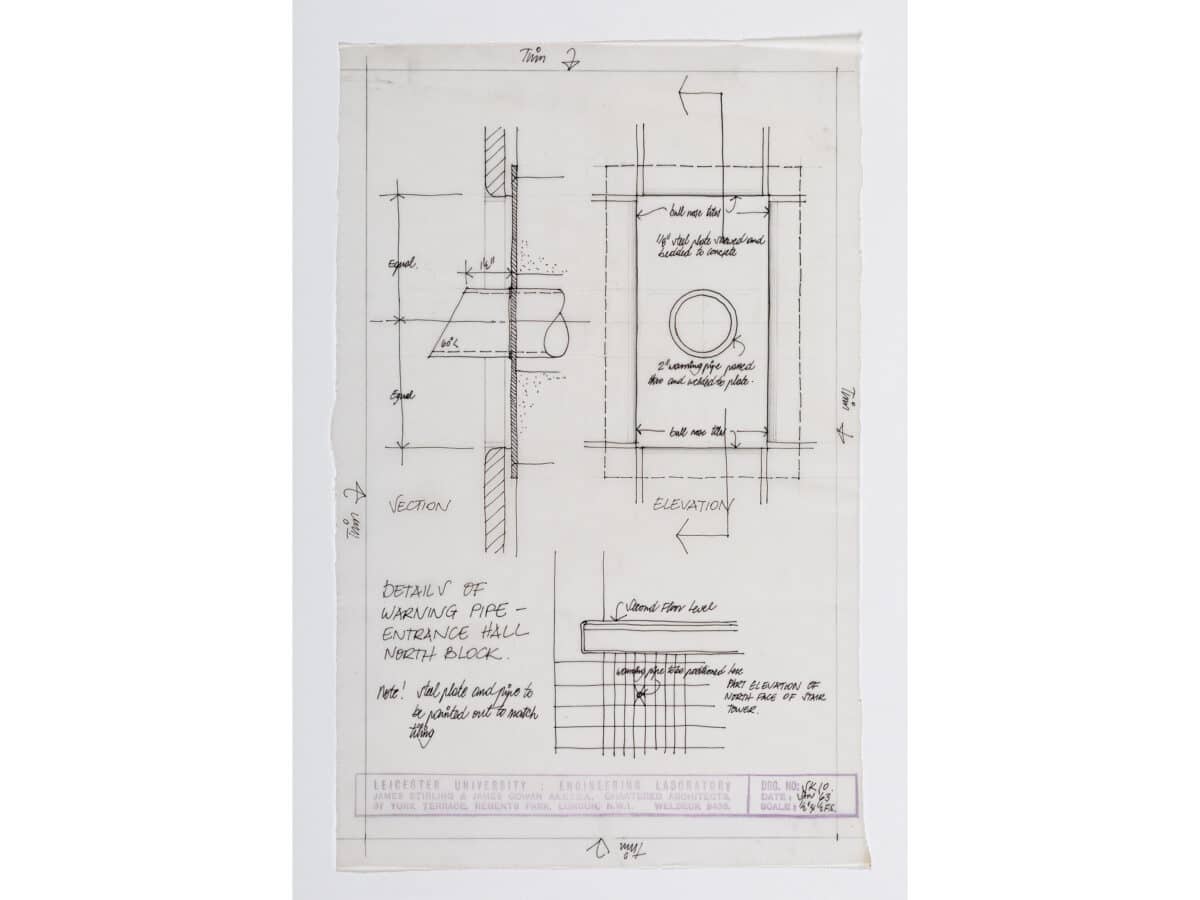

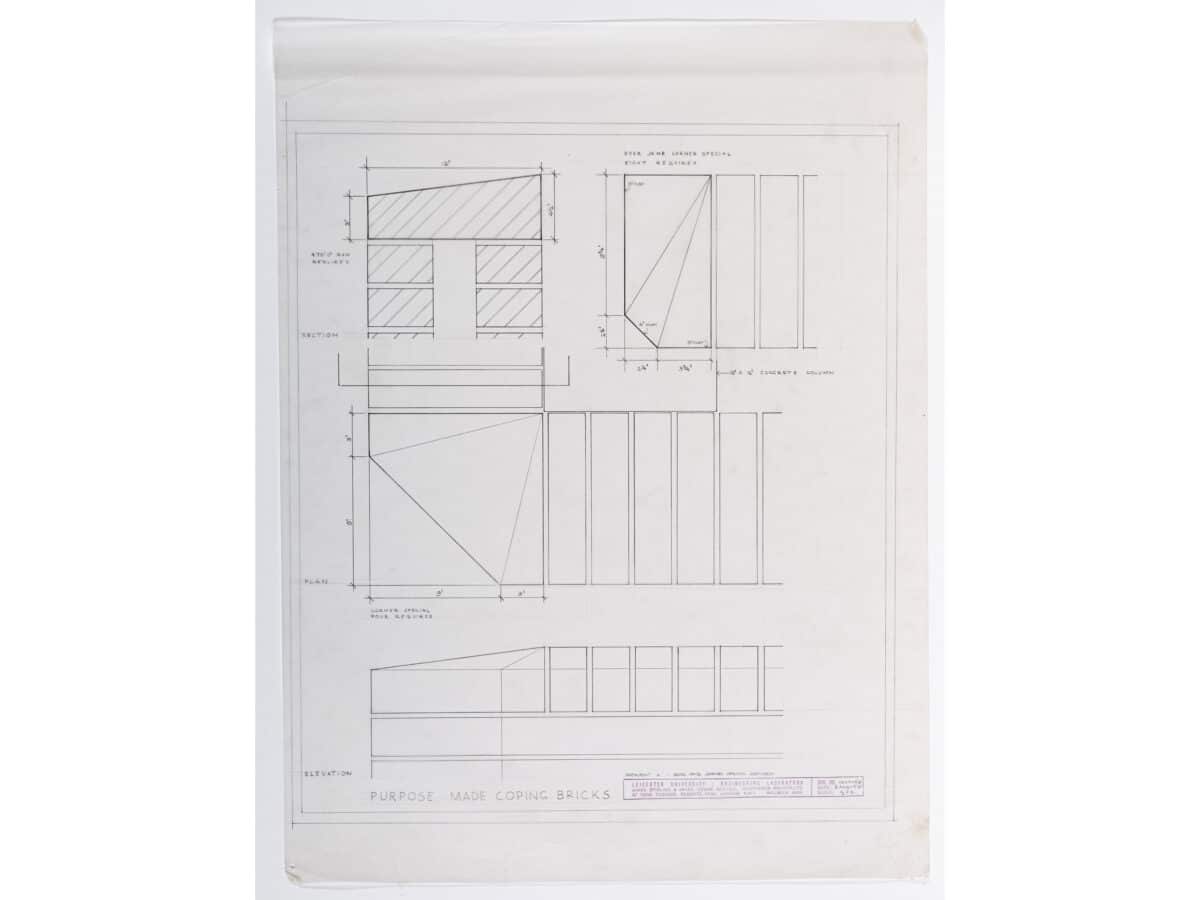

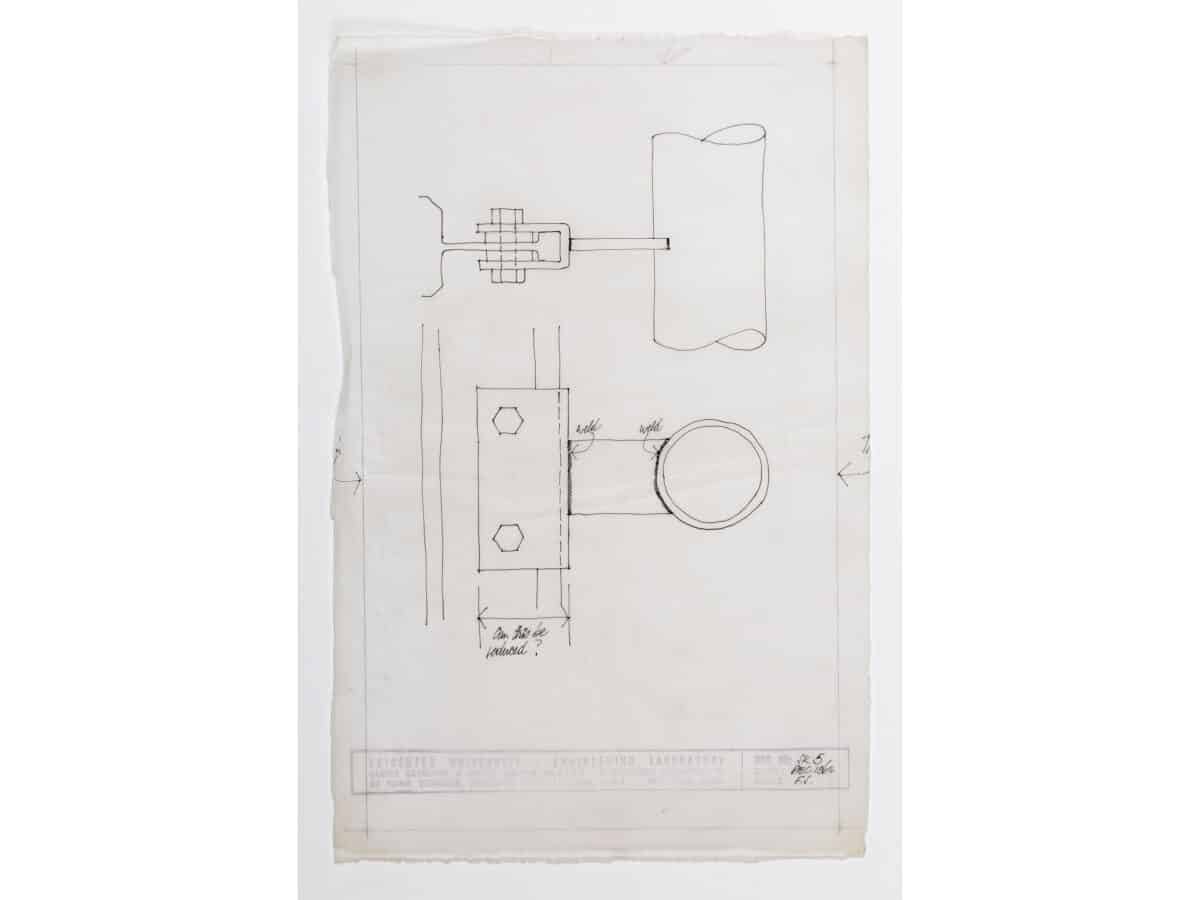

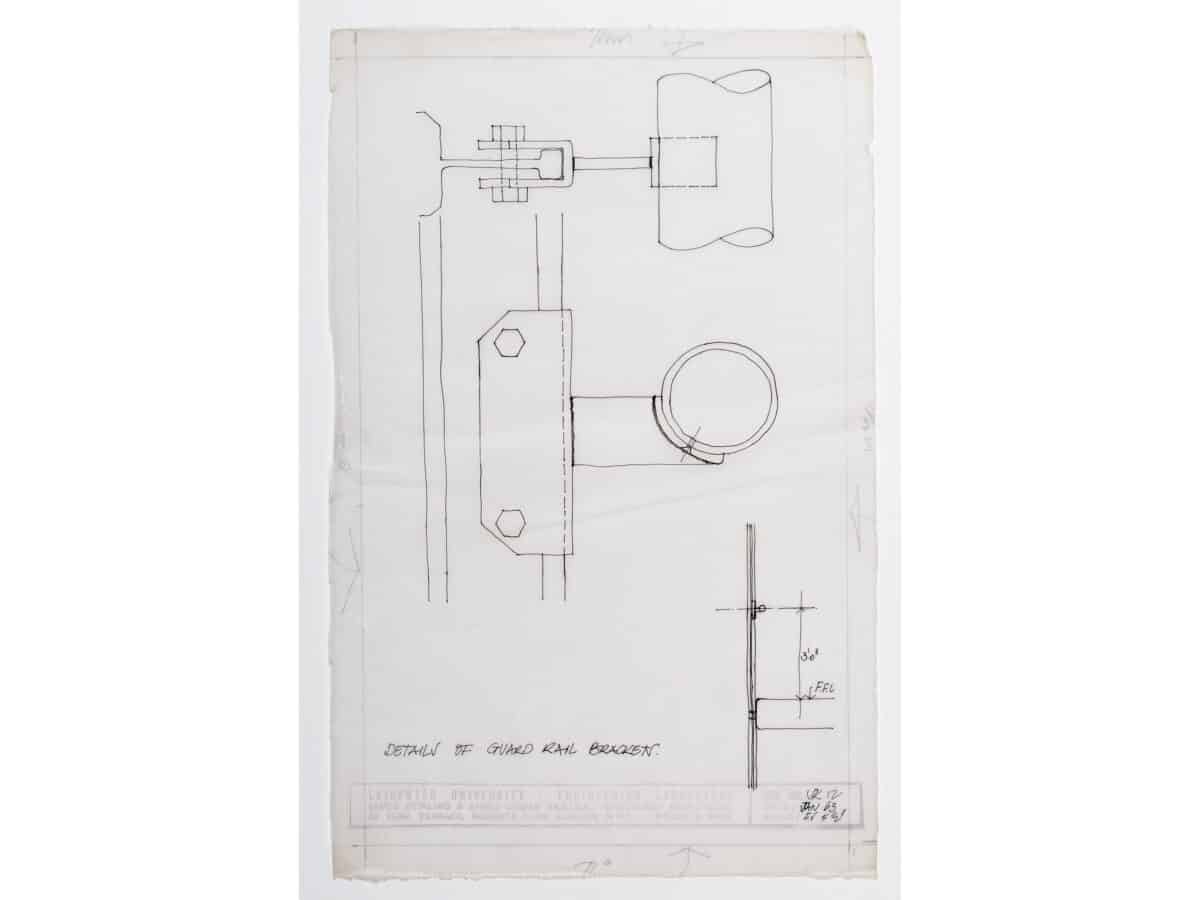

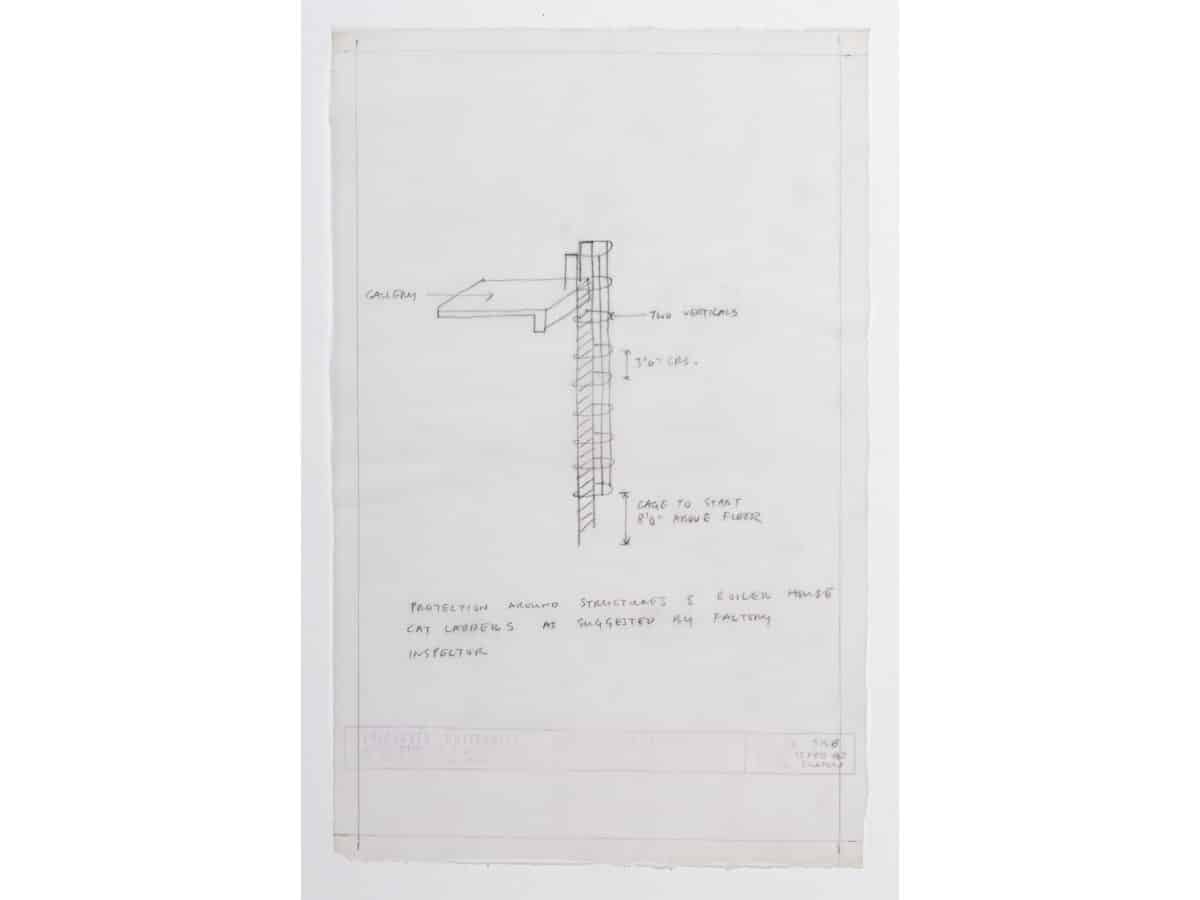

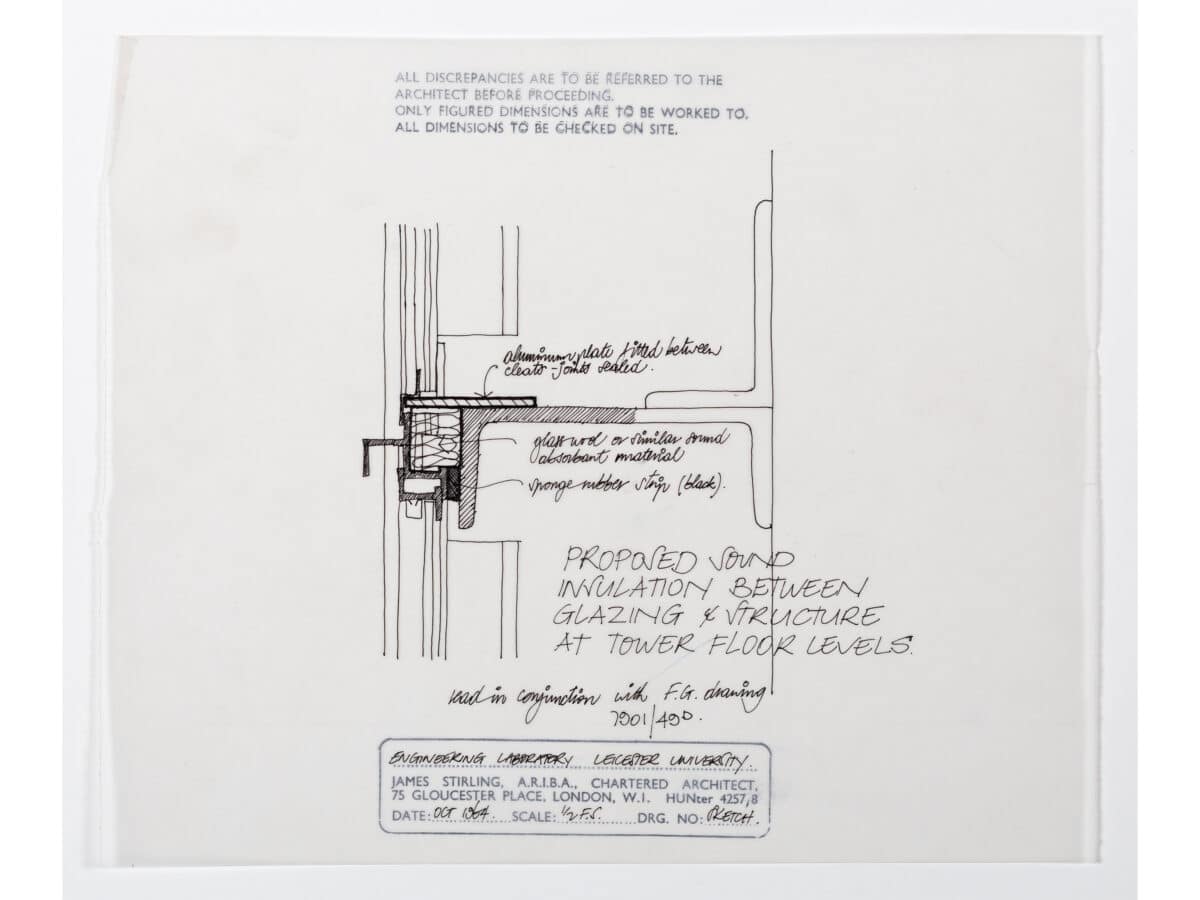

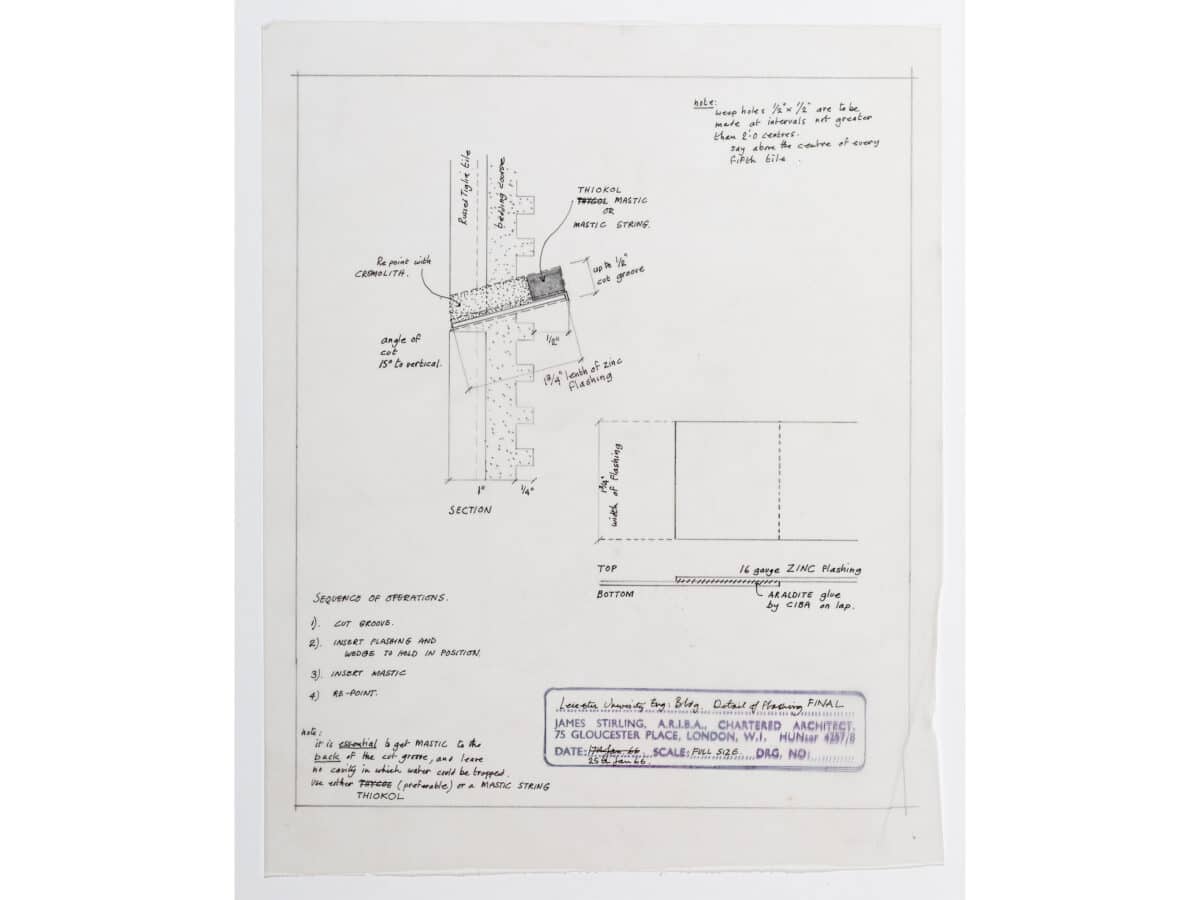

Between these two main towers rise three subsidiary shafts—a twinned pair for lifts and stairs rising the full height of the admin tower, a smaller one standing only high enough to serve the lower research tower. Where these five clustering towers do not touch—which is usually—the intervening spaces are filled by glazing that in only one case (between the twins) falls sheer and vertical to the ground. In the other gaps it descends in a sort of cascade, twisting to one side or the other, and angling forward to accommodate the ever-larger landings that are needed in the lower and more populous parts of the building. This composition of towers and glass is a fantastic invention, the more so because it proceeds rigorously from structural and circulatory considerations without frills or artwork. The solid walls are either of the same brick as the podium, or of the red tiling that covers nearly every square foot of concrete, even floors and ceilings. The glazing (like the tiling) is rock-bottom cheap industrial stuff, just glass and aluminium extrusions. It has no pretty details, just nuts, bolts, bars cut to length on site, and raggedy flashings left ‘as found’.

By taking a thoroughly relaxed attitude to technology and letting the glazing system follow its own unpretentious logic, the architects achieved less a kind of anti-detailing (as some critics seem to suggest) than some form of un-detailing that would border on plain dereliction of duty were it not so patently right in this context. But over and above the rectitude of the detailing, the stair-tower complex offers such bewildering visual effects that words are apt to fail. Both by day and by night (when the stairs are lit by pairs of plain industrial lamps bracketed from the walls) the play of reflections in the variously angled glass surfaces can be as breathtaking as it is baffling. It really looks as if the grand old myths of functionalism have come true for once, and that beauty, of a sort, has been given as a bonus for the honest service of need.

I say beauty ‘of a sort’ because the visual pleasures of this complex and rewarding building are neither those of classic regularity nor picturesque softness. Its aesthetic satisfactions stem from a tough-minded, blunt-spoken expertise that convinces even laymen that everything is right, proper and just so. It is one of those buildings that establishes its own rules, convinces by the coherence of markedly dissimilar parts, and stands upon no precedents. It rebuffs the attempts of art-historians to identify its sources (unlike some of the other modern buildings on the Leicester campus, which provide a real feast for art-historical nit-pickers), though it has, in some obtuse way, of its own, regained a good deal of the bloody-minded élan and sheer zing of the pioneer modernism of the early Twenties. […]

Excerpted from Reyner Banham, ‘The Style for the Job’, New Statesman, 14 February 1964. This text is included in the December 2024 issue of Casabella, which is dedicated to the work of James Stirling and illustrated with material from Drawing Matter Collections.