‘ONE’ — A Workshop at Drawing Matter

– Charles Batach, Fabrizio Gallanti, Youssef Khobaiz, Marina Lathouri, Katerina Papanikolopoulos, Roberto Rodriguez and Freny Shah

This article tries to convey the collective exhilaration of a week-long seminar with Drawing Matter: five days, four writing exercises based on the analysis, observation and writing of archival and graphic material from the Drawing Matter Collection.

Since 2014, the History and Critical Thinking postgraduate programme at the Architectural Association in London has developed in collaboration with Fabrizio Gallanti a one-week seminar titled Design by Words, whose objective has been to experiment with forms, genres, and styles of architectural writing. Over the years, a series of writing exercises, smaller and larger pieces of craft, has constituted the methodology of the seminars: students are asked to seek concision, clarity and directness. The intention has been to hone their writing skills, a kind of experiment, through short and intense texts, in voice, tone, genre or structure. It is an experiment in which speed—assignments change from one morning to the next—allows risk, opens possibilities, but also helps with the understanding that each single word matters and that redundancy and excessive verbiage might be detrimental for the clear communication of ideas.

In past years, the writing exercises often dealt with issues of description and translation: a space, a building, a real situation in the city, had to be distilled and narrated in a few words. Authors as varied as Reyner Banham, Joan Didion, Georges Perec and the Oulipo, or Walter Benjamin have been presented as references of clear, direct writing, yet wonderfully rich in their capacity to communicate just by words the feeling and sense of a place. For the 2025 seminar, the workshop, now part of the course Unpacking the Archive: Mediality and Evidence, neither buildings nor places were to be described, but archival materials instead, more specifically architectural drawings. The intention was, among others, to dive into the legacies of architectural publishing, where the relation of images and texts has been played out in illustrated books and magazines, as well as exhibition-making, where the mediation that text can generate about visual content occurs on walls.

The natural place to explore such potential is the collection of Drawing Matter. The team at DM was excited by a speculative approach to the description of a selection of drawings from the collection, providing ample support and constant engagement for the individual exercises. Each exercise was composed of two parts. In the morning at Drawing Matter, drawings were presented for discussion and selection. The identity of the authors of the drawings was camouflaged, when possible, to direct and focus the attention to the inherent qualities of the material itself. In the late afternoon at the Architectural Association, each participant read the assigned writing for the day. Writing to a short, set length, formulating an immediate response to the material was combined with working in a group and reading the pieces aloud.

Not only did Drawing Matter give the students access to its archives, but orchestrated a generous mise-en-scène of its holdings, which culminated in the final presentation, where readings and sheets over sheets of drawings populated the tables, inciting the conversation between students, the staff of Drawing Matter and invited guests—Shumi Bose, Ingrid Schroder and Ellis Woodman.

— Marina Lathouri & Fabrizio Gallanti

One Individual Drawing

Drawings selected by Rosie Ellison-Balaam

Anonymised drawings (lightbox)

Drawings by unknown authors (lightbox)

Drawings by known authors (lightbox)

Exercise: Alt Text

Write three short texts, maximum 1-2 sentences long each, describing three selected documents: one anonymous, one whose author has been obfuscated, and one whose author is known. These texts should operate as Alt Text, texts accompanying images, incorporated on websites to facilitate accessibility, in particular for audiences with visual impairment.

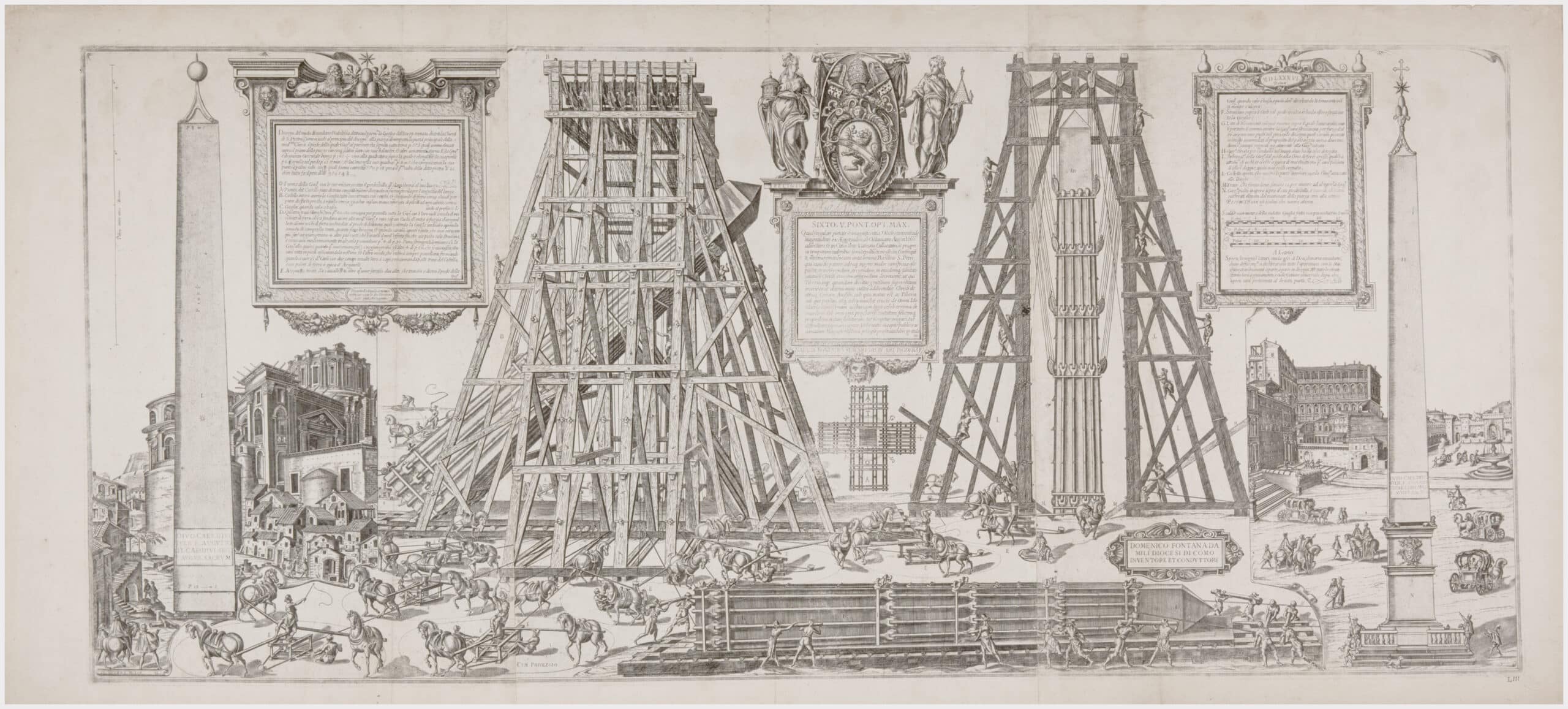

The complexity of the process for the transportation of an Obelisk to its new location in front of St. Peter’s Basilica is depicted through an assembly of illustrations and texts that follow crucial phases of its procession. The manipulation of a colossal structure is achieved by employing a machine-like system of scaffolding and poles powered by a large number of horses and humans, each of them conducting rhythmical movements that create an orchestra of intense labour.

— Roberto Rodriguez

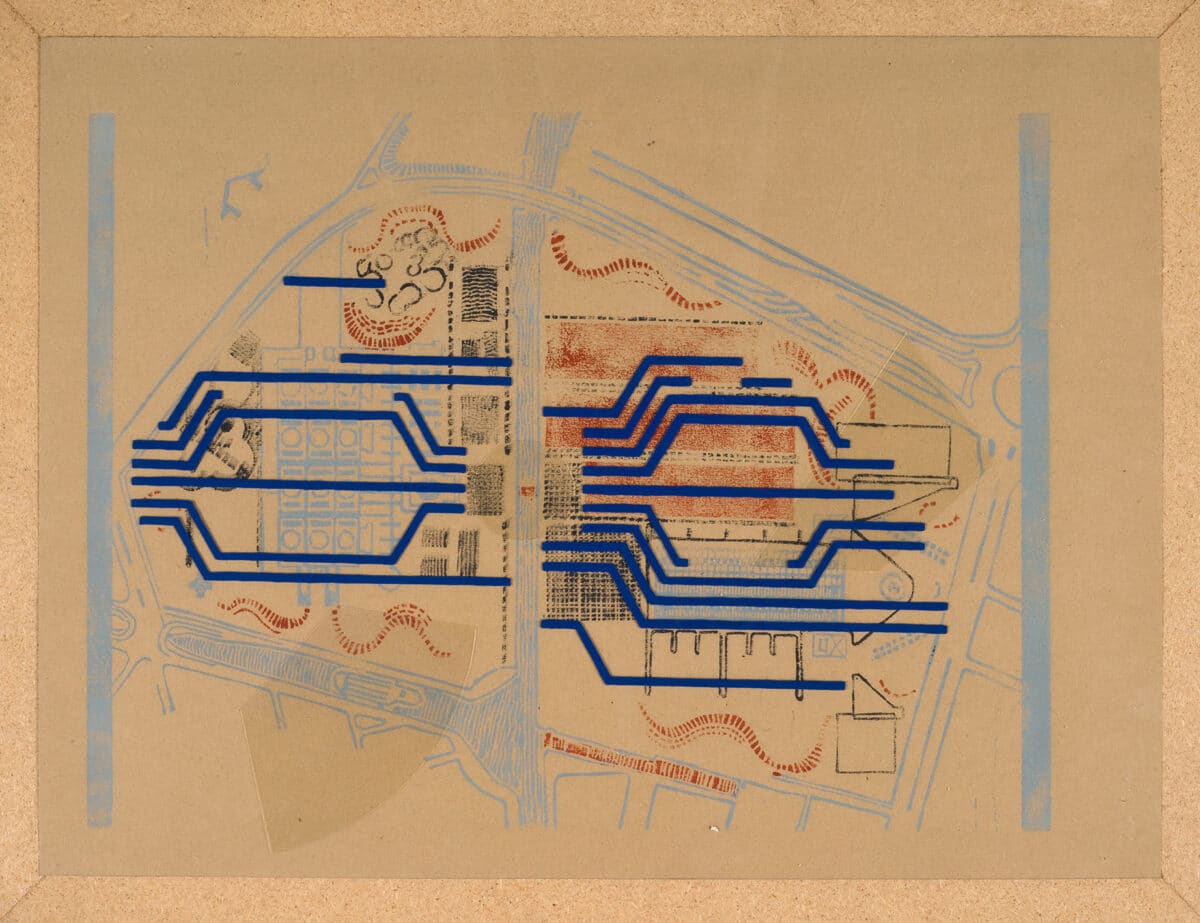

Layers of decisions and information are juxtaposed in a conceptual diagram. Coloured drawings and hatches are superimposed with translucent masses and thick blue lines, articulating the architect’s spatial vision; part of the Parc de la Villette competition entry, 1982.

— Youssef Khobaiz

The transparent glass sphere, by Italian designer Enzo Mari, contains a suspended three-dimensional wireframe grid that shifts and deforms optically as the viewer moves around it. Mari’s signature on one location of the sphere’s surface gives the otherwise orientation-less object an unintended point of orientation.

— Charles Batach

One Project—a set of drawings of the same architectural project

Drawings selected by Martha Cruz

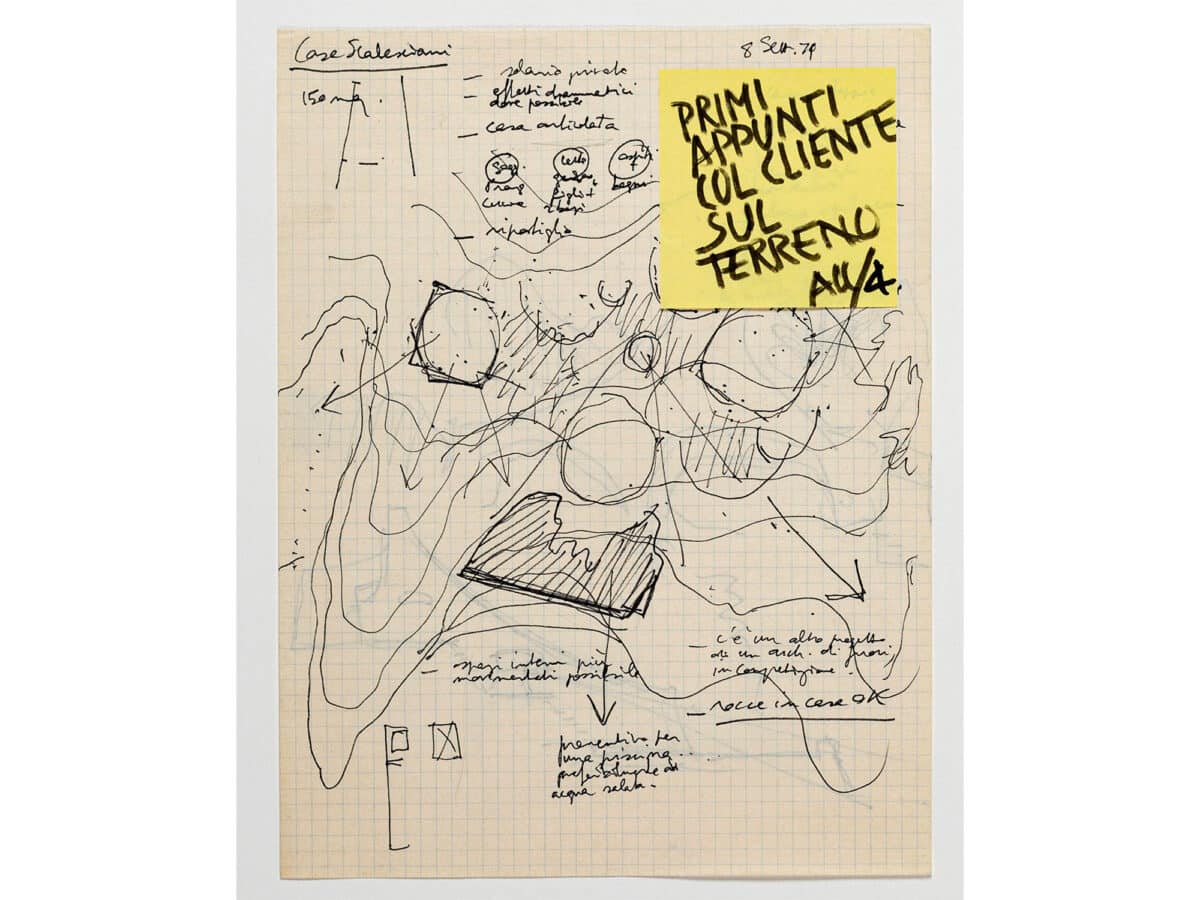

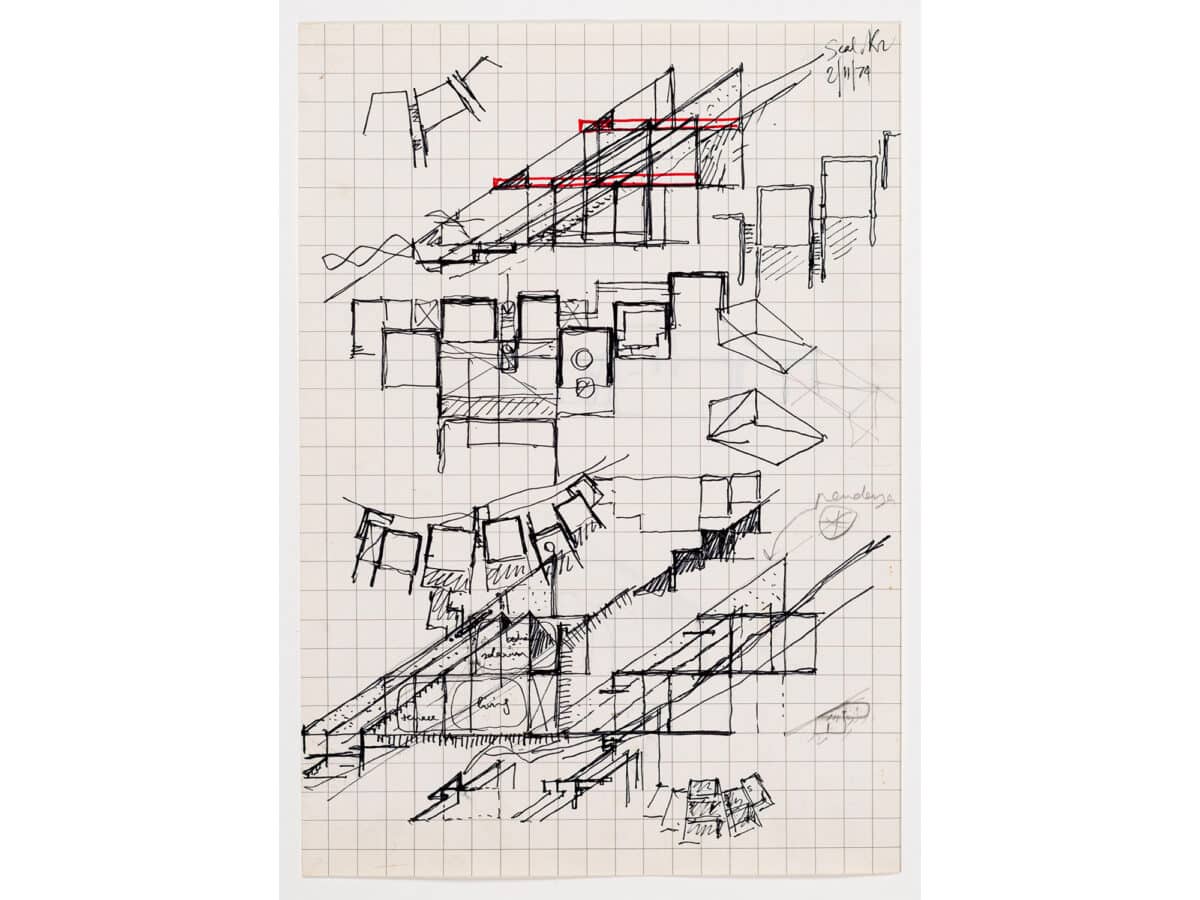

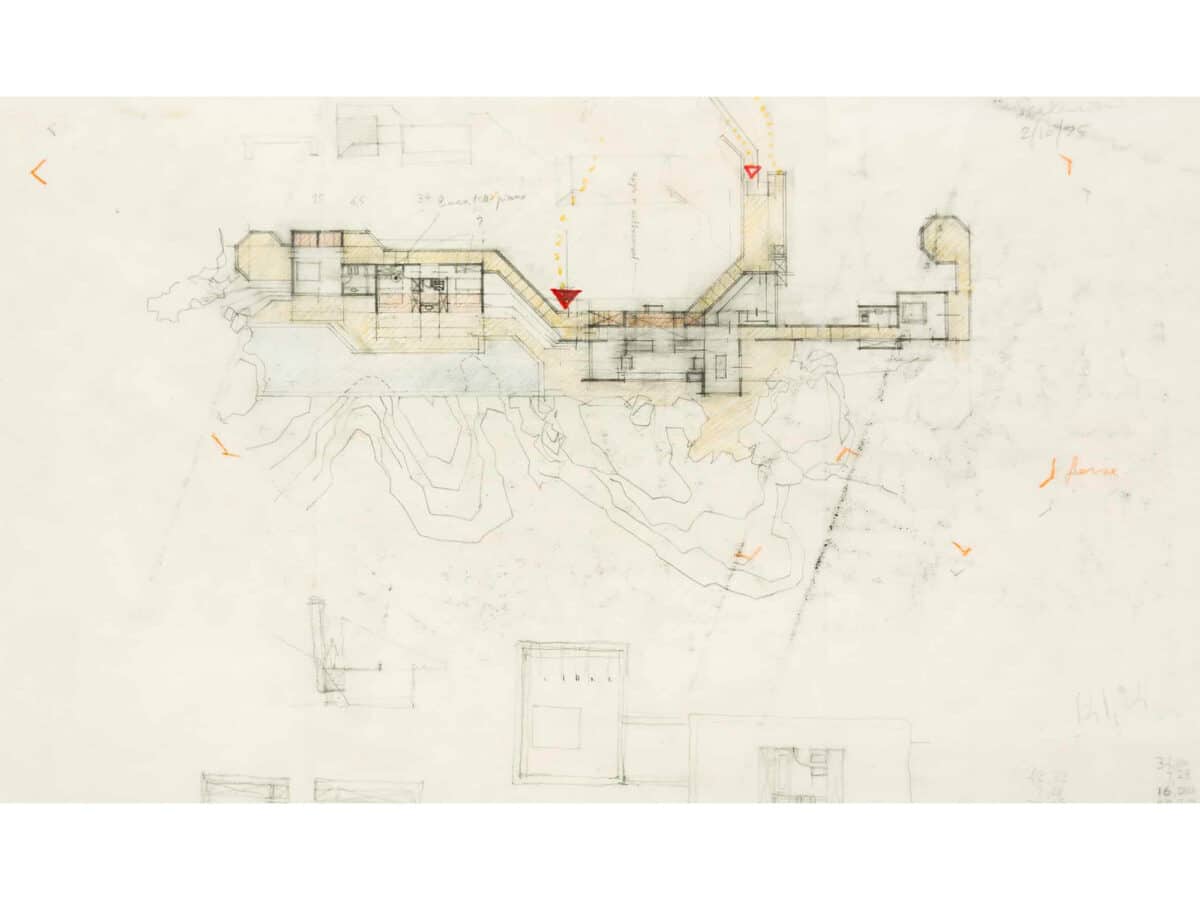

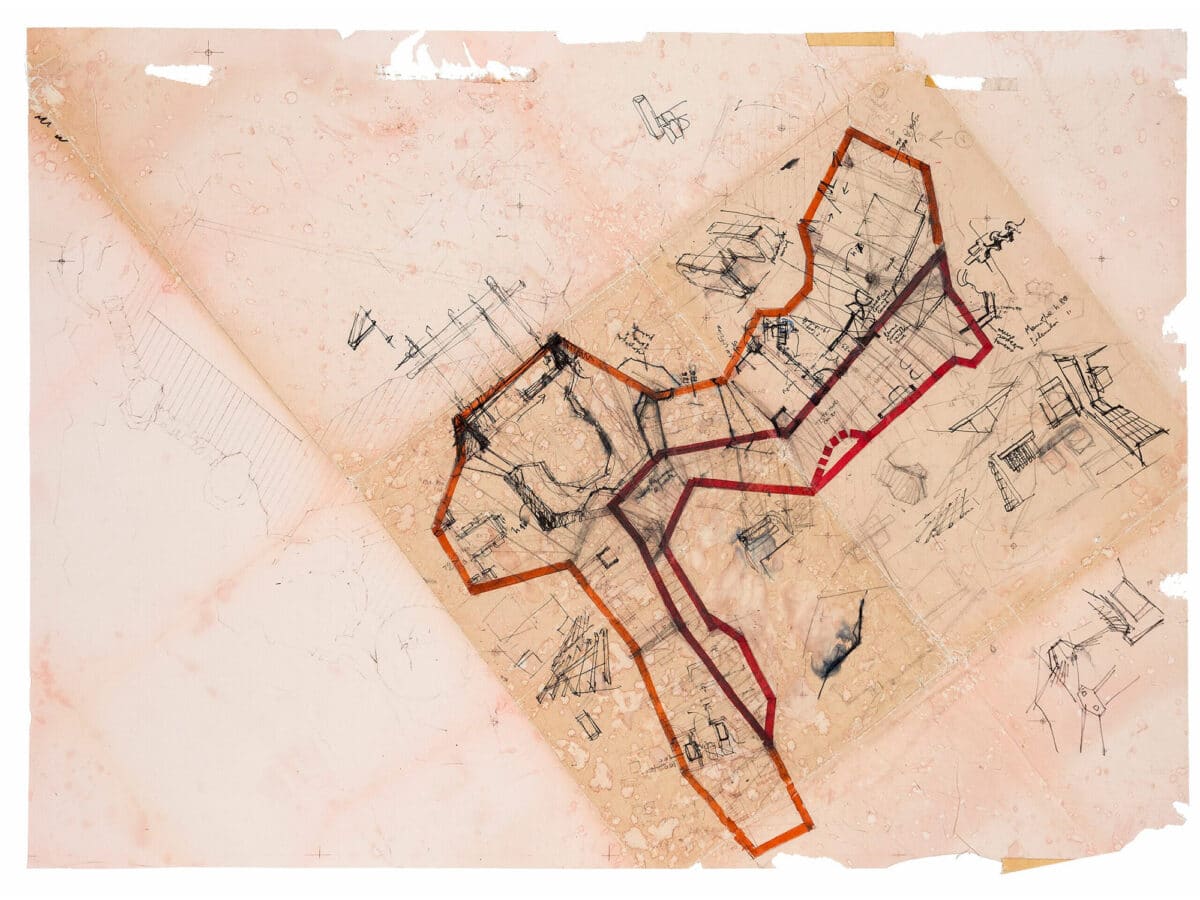

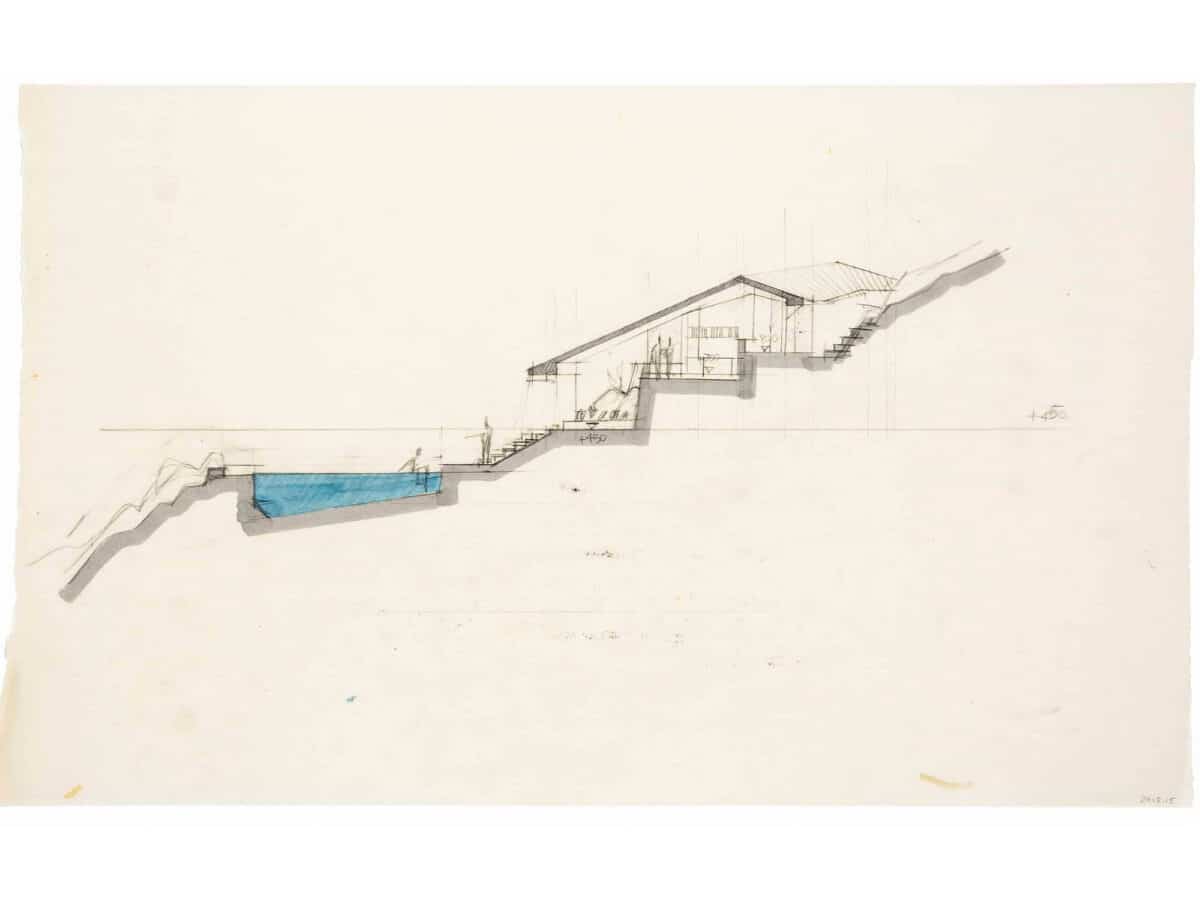

Alberto Ponis, Casa Scalesciani

Peter Wilson, Clandeboye

Tony Fretton, Lisson Gallery 2 (Facade focus)

Bolles+Wilson, Luxor and Kop Van Zuid

James Gowan, East Hanningfield

Aldo Van Eyck, Four Tower House

Louis Kahn, Kansas City Tower

Álvaro Siza, Malagueira (Cupola)

Exercise: Captioning

Establish a linear sequence (from 1 to N), of at least 10 documents. For each write an extended caption, that can balance description and interpretation. This extended caption can include references to previous or consecutive captions in the sequence. Each extended caption should not exceed 250 words (ideally less).

Alberto Ponis, Casa Scalesciani

— Roberto Rodriguez

One Technique—a set of drawings from different historical periods, characterised by the same drawing technique

Drawings selected by Maria Mitsoula

Exercise: Comparative collage

Select a minimum of three, maximum of six documents. Write a short group text (reference ‘Wall texts in collection exhibitions. Bastions of enlightenment and interfaces for experience’ by Palmyre Pierroux & Anne Qvale), explaining differences and similarities between the documents in relation to collage as a technique for architecture. Historical references and citations can be included. Length: 500 words maximum.

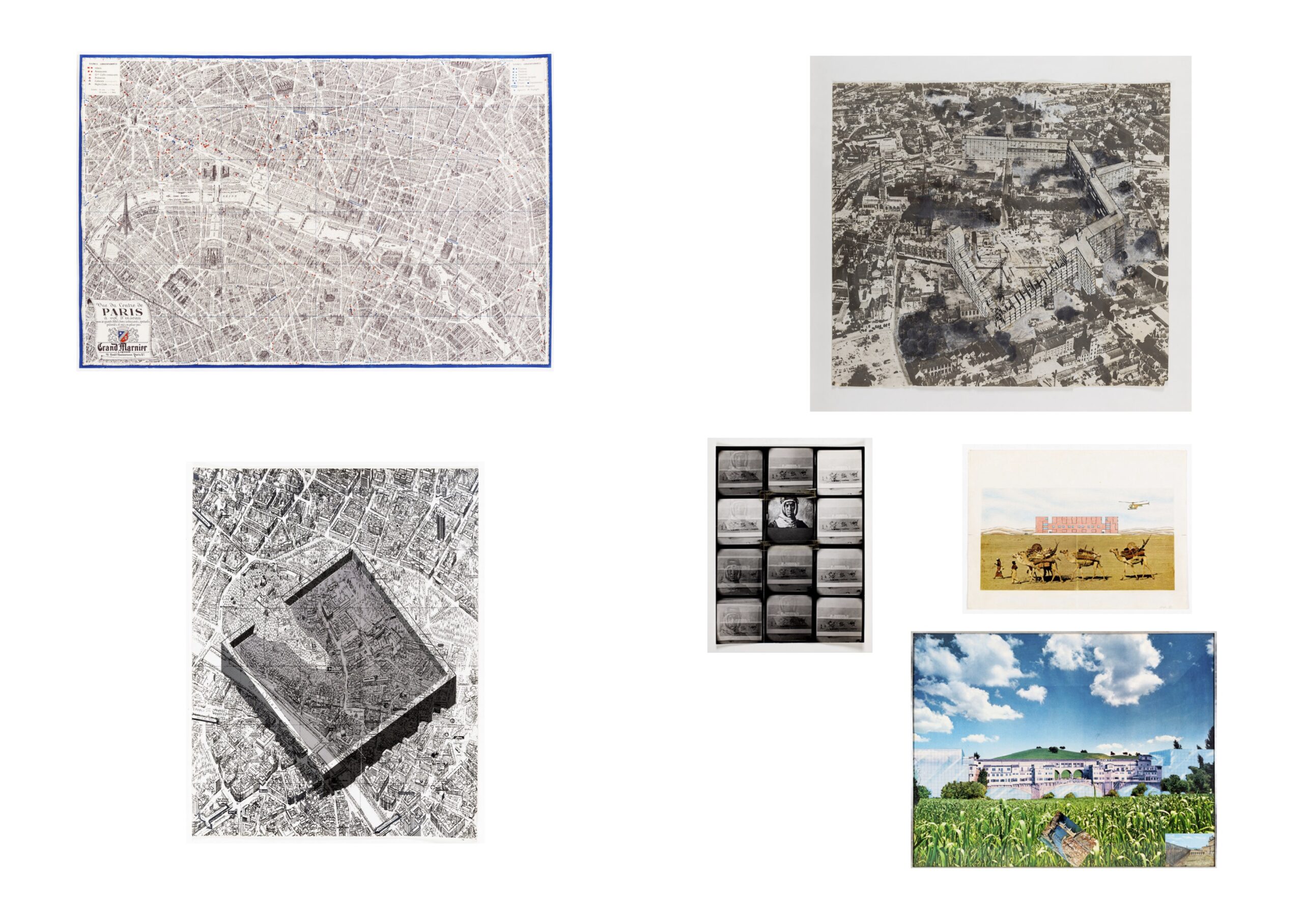

Collage

Collaging is a medium that constructs stories and worlds by necessitating decontextualisation and discontinuity, and requiring an active choice between what should and should not be shown to articulate a narrative; in order for one image, or one part of an image, to be shown or highlighted, another aspect must be obscured, discarded, drawn over, or folded behind. The following selected works showcase how artists throughout twentieth-century Europe have used a technique of obfuscation in order to evoke a larger sense of loss within urban and architectural environments.

The urban environment is shown as breaking, fragmented, or decaying, with a consistent sense of urban loss running through each work. In some works, this sense of urban loss is conveyed literally: for instance, Competition for the Monument to the Fallen of Como (1925-26) by Giuseppe Terragni, or Graz: Flooding in Dry Ice by Superstudio. In the first work, the sense of loss is conveyed through the solemn and evocative nature of the building as funerary architecture, while in the second work, the sense of loss is conveyed visually through the submerged city. For Guy Debord and Jiří Kolář, the sense of loss is articulated through obvious fragmentations. Debord’s Guide Psychogeographique de Paris breaks apart and reassembles the map of Paris, rendering transitory spaces as voids. Jiří Kolář’s Crumplage explores urban fragmentation by folding an engraving of the Royal Courts of Justice in London upon itself, producing an image of the courts falling apart under their own weight and creating a narrative of chaos and the dissolution of the cornerstones of civil life.

A common thread explored is the theme of tabula rasa. One of the ways that this theme is articulated through these works is through isolated constructions. Gowan’s Greenwich Housing Project Reimagined decontextualises a housing project and displaces it into a flat desert landscape. Contrasting this approach is Alison and Peter Smithson’s Urban Re-Identification Project, which treats the existing urban landscape, in essence, as an empty canvas. The theme is also explored through images of destruction. In Mario Ramos and Fernando Barroso’s Organizaçāo Insurrectonal do Espaço, urban environments are devoured and lost to nature, creating an impression of a tabula rasa in the truest sense; traces of the urban past remain, but only buried and forgotten.

The themes explored in the content are reflected in the medium of collaging itself. Something must be hidden or dislocated from its context in order to create an image at all. At the heart of these works, there is an intrinsic association between architecture and the types of memories we hold on to. Each collage positions a provocation of amnesia and remembrance through the themes of loss, fragmentation, and urban decay.

— Freny Shah

*

A Blind Man’s Equality

‘Conscious of my ability to see, I look at the vast objective metaphysics of the skies with a certainty that makes me want to die singing. “I am equal in size to whatever I see!” And the vague moonlight, entirely mine, begins to mar with its vagueness the almost black blueness of the horizon.’

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet (p. 103)

Where there is a visible subversion of the established system, and a city begins to sink, the Portuguese author Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet (1913-35) provides a yearning for the recognition of a potential equalising sight—’I am equal in size to whatever I see!’ A city whose purpose and scale cease to serve its citizens produces a form of A Blind Man’s Equality—where photo-montage and collage are negotiated as an instrument to enforce a new autonomy of intervention on the city’s urban infrastructure. Situated between the the metaphysical, social, and spiritual life of a civic identity, subversive political regimes are articulated transculturally in Portugal, the United Kingdom, and Italy through this reflective medium of representation.

A Blind Man’s Elemental Return to the Navel of Primary Space and Object

Fernando Barroso and Mário Ramos’ extant archive of photo-montages from 1975 within the collections of Drawing Matter propagates such anomalies of ‘certainty’ to be investigated within the time-sensitive medium of collage. Porto’s landmark social institutions—those of religion, of national banks, and prestige drown into a preparatory soil of an ocean bed (echoing the 1968 utopian ideal ‘Sous les pavés, la plage!’ (‘Under the paving stones, the beach!’). In this weight of disorientation, the collages propose an alternate reality—centralising the role of forced, collapsing time in the image of a sinking clock tower. Peter and Alison Smithson’s Urban Re-Identification Project in the United Kingdom, projected the medium of collage as a means to superimpose the inert neutrality of an existing plane—how the soil and brick can be overturned and built upon figuratively at the slight of a hand. The oeuvre of Guy Debord, Guide Psychogeographique de Paris, Discours sur les Passions de l’Amour (1957) Figure 2302 problematises the fragmentation inherent in the medium of collage—to produce a cartographic requiem for Paris’s most frequented crossing, denoted to the viewer in a red annotation—choreographing a ‘way to view’ that is both performative and disruptive. In this hand-holding that collage allows for, The Competition for the Monument to the Fallen of Como (1925-26), Italy, (Terragni, Fig. 3689) provides an iconic stage for grieving providing an atmospheric pulse to a grave reality. One’s concern with proximity to death has alluded architecture’s stronghold on permanence. In comparison, the 1971 sequence of overdrawn photos ‘flooding in dry ice’ proposed by Superstudio (Fig. 2156.9) also succeeds in the intrahuman rendering of an environment’s capacity. The monument(s) are encased in a non-reality that cannot be realised on earth, but their presence can be felt on another viable field of vision. The form of collage becomes seminal ‘eyes’ into the layered neurosis of creation—able to witness the assemblage of senses that is so intrinsic to the practice, and its real-time manifestation as the palpable is imagined and constructed in true time.

— Katerina Papanikolopoulos

**

The City of The Future, 2025

Welcome to The City of the Future™—a visionary urban model assembled from the very forces shaping our contemporary condition. Here, fragmentation becomes an asset, distortion becomes innovation, and every unresolved tension is reintroduced as a selling point. What you encounter in this collection is not a hypothetical projection but a polished preview of the urban realities we are already building.

In this future, coherence is no longer a prerequisite for city-making. Instead, the metropolis is proudly presented as an assemblage of disconnected parts: isolated districts, abrupt material shifts, incompatible scales, and competing narratives, each marketed as a unique ‘experience.’ The seamless city is outdated; the fragmented city is the new premium product.

Time is a central amenity in this model. It stretches, collapses, accelerates, and freezes across the urban field. Construction races forward while memory stalls; heritage is selectively fast-tracked into aesthetic shorthand; and futures are announced long before they exist. This temporal instability is not treated as a flaw, but as evidence of a highly dynamic urban metabolism—one that promises perpetual reinvention without ever addressing what came before.

Desert Dream Urbanism™ plays a leading role in the branding of tomorrow. Monumental structures rise confidently from fragile landscapes, engineered to project ambition while quietly depending on ecological extraction. These visions promise permanence in territories defined by impermanence, offering stability as spectacle rather than practice.

Meanwhile, curated Arab identity becomes a key feature of our offered package. Heritage is distilled into instantly recognisable motifs—stone cladding, arches, earthy palettes—deployed not as cultural continuity but as marketable ambiance. History, in this city, is delivered as a premium texture: evocative, efficient, and easily applied.

Echoes of Superstudio’s critique surface throughout this promotional landscape. What was once a warning—the endless monument, the homogenized grid—returns now as a desirable upgrade. Our future city proudly merges planetary-scale modernity with boutique heritage fragments, producing a skyline that is equal parts nostalgia and impossibility. and in keeping with the logic of this future, even the narration of the city no longer belongs to a single author.

This text was written by ChatGPT. The prompting process was intentional and deliberate. I began by curating the visual material myself, assembling it into a single image and writing the initial concept, as well as an outline for the text. Afterwards, I started to work with ChatGPT.

Firstly, I asked ChatGPT to recognise and describe some of the visual material in order to establish a defined frame for the topic. I then introduced the concept text without revealing the actual task—writing a wall text. Once the topic and the conceptual logic were set, I initiated a discussion about potential writing tones for the text, which I already had in mind.

At the end, I revealed the task, entered my outline, and chose the tone in which the text was written. Following this, I carried out the final edits and refinements myself.

ChatGPT is a chat-based engine. I micromanage it by entering the data gradually, in order for the output to remain mine and not the model’s. Authority is lost when the model is asked to perform a task using a single prompt.

— Youssef Khobaiz

One Author—a set of drawings by the same architect and from different phases of her/his work.

Drawings selected by Jesper Authen

James Gowan

Erik Gunnar Asplund

Peter Wilson

Viollet Le Duc

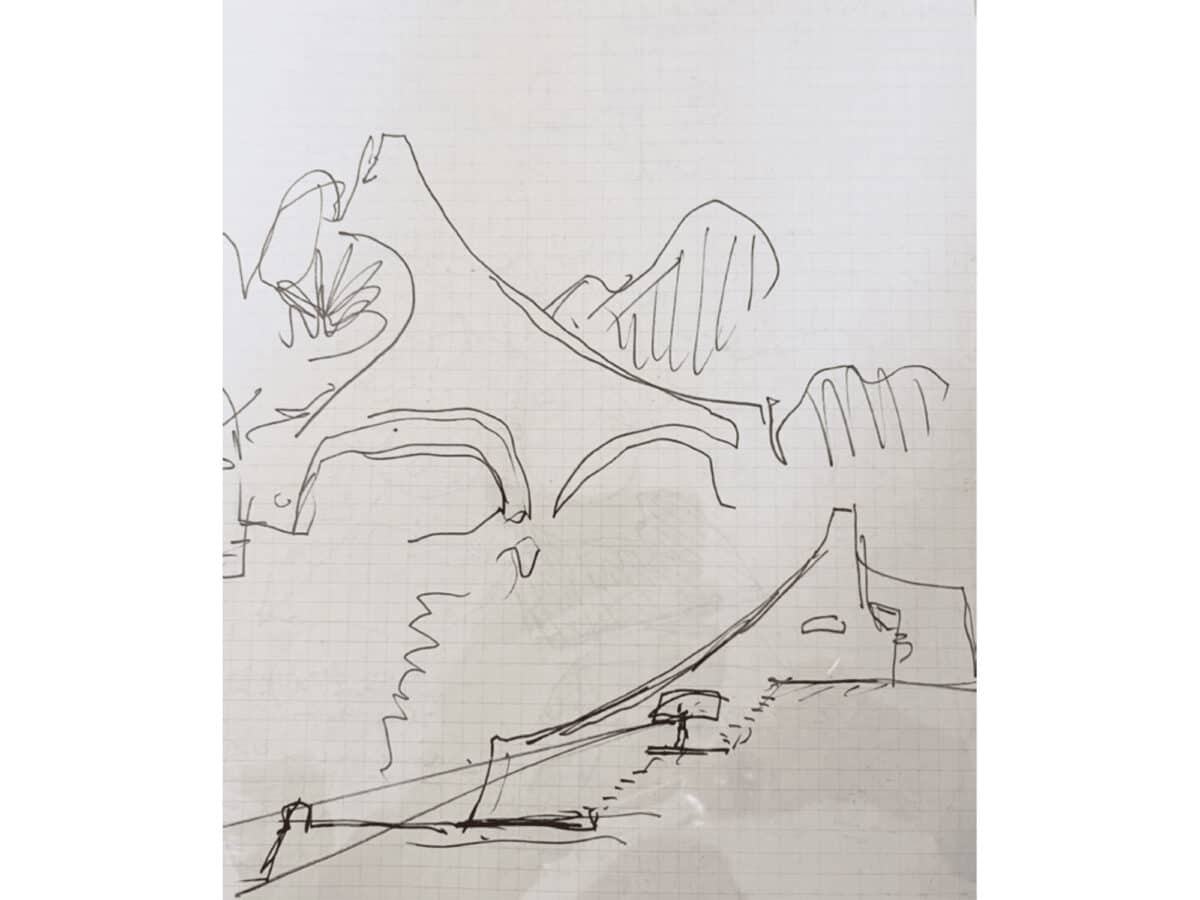

Zaha Hadid

Louis-Hippolyte Lebas

Exercise: Biography

Based on the presented material, develop a fictional biographical entry for the MoMA website (Alvar Aalto or Álvaro Siza or Lina Bo Bardi or others).

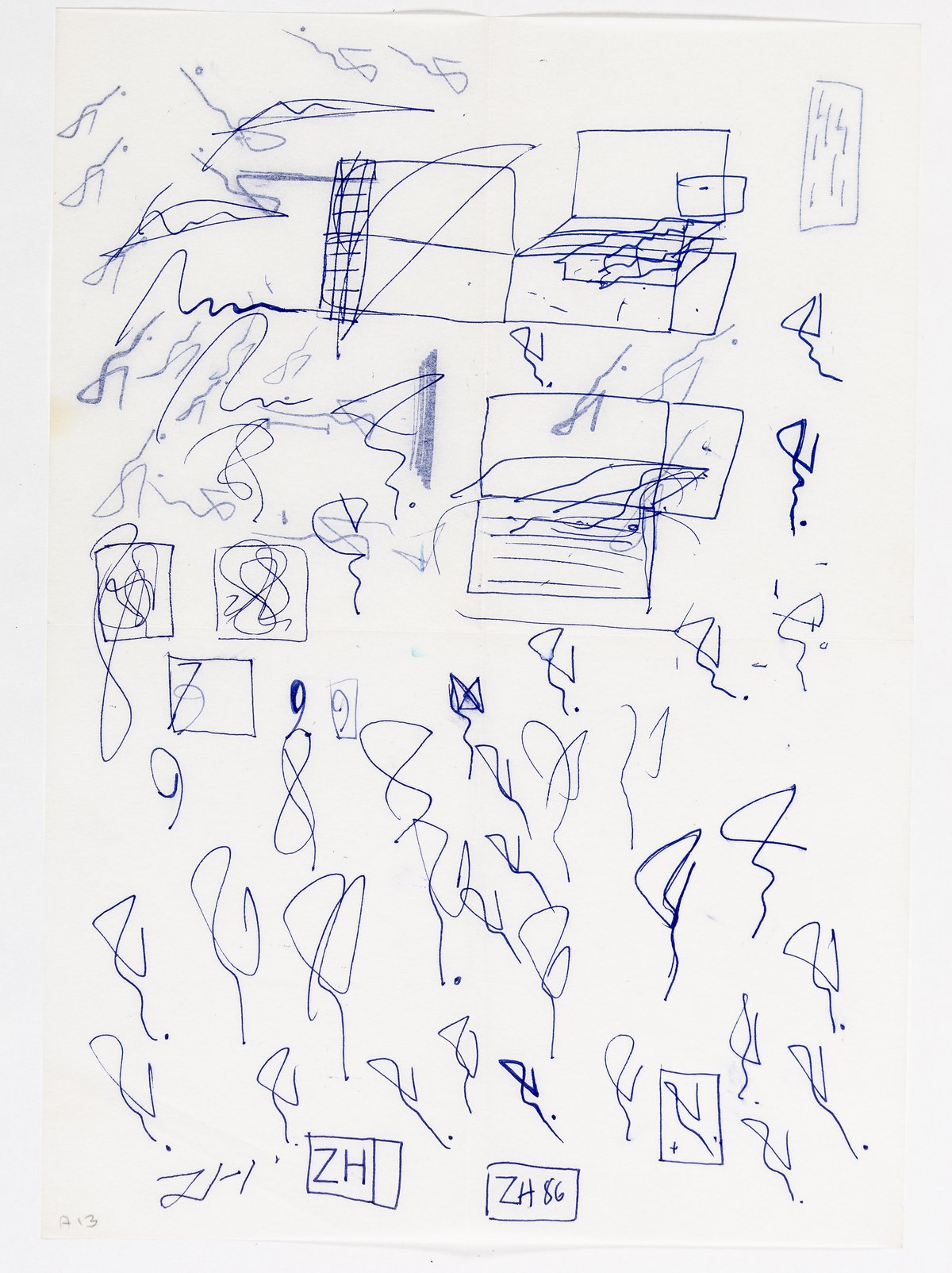

ZaHaDid

‘At times the signature escapes me, reappearing as something unintended — a fragment, a pathway, the beginning of a form.’

ZaHaDid’s contributions to architectural modernity followed an unusual path, establishing her as one of the most experimental figures of her generation. She initiated an inquiry into the self, researching her voice and her imprint as a way of constructing a persona.

On hotel stationery, thin drafting sheets, and the loose margins of notebooks, she developed a signature that functioned as an early form of architectural writing. These inscriptions, now present in the MoMA collection, move fluidly between calligraphy, diagram, and ideogram. Across the sheets, the line continually negotiates between Arabic and English, often folding the two scripts into a single bidirectional gesture: a mark that reads left to right as easily as right to left. In this hybrid form, the signature swells into looping curves that recall ornamental calligraphic traditions while simultaneously fracturing into angular vectors that anticipate the geometric tensions of her later drawings. In both languages, the line stretches beyond the function of an autograph: it elongates, tilts, and oscillates, becoming at once a gesture, a notation, and a proto-architectural proposition—an expression of liquid identity moving effortlessly between cultures, scales, and spatial imaginaries.

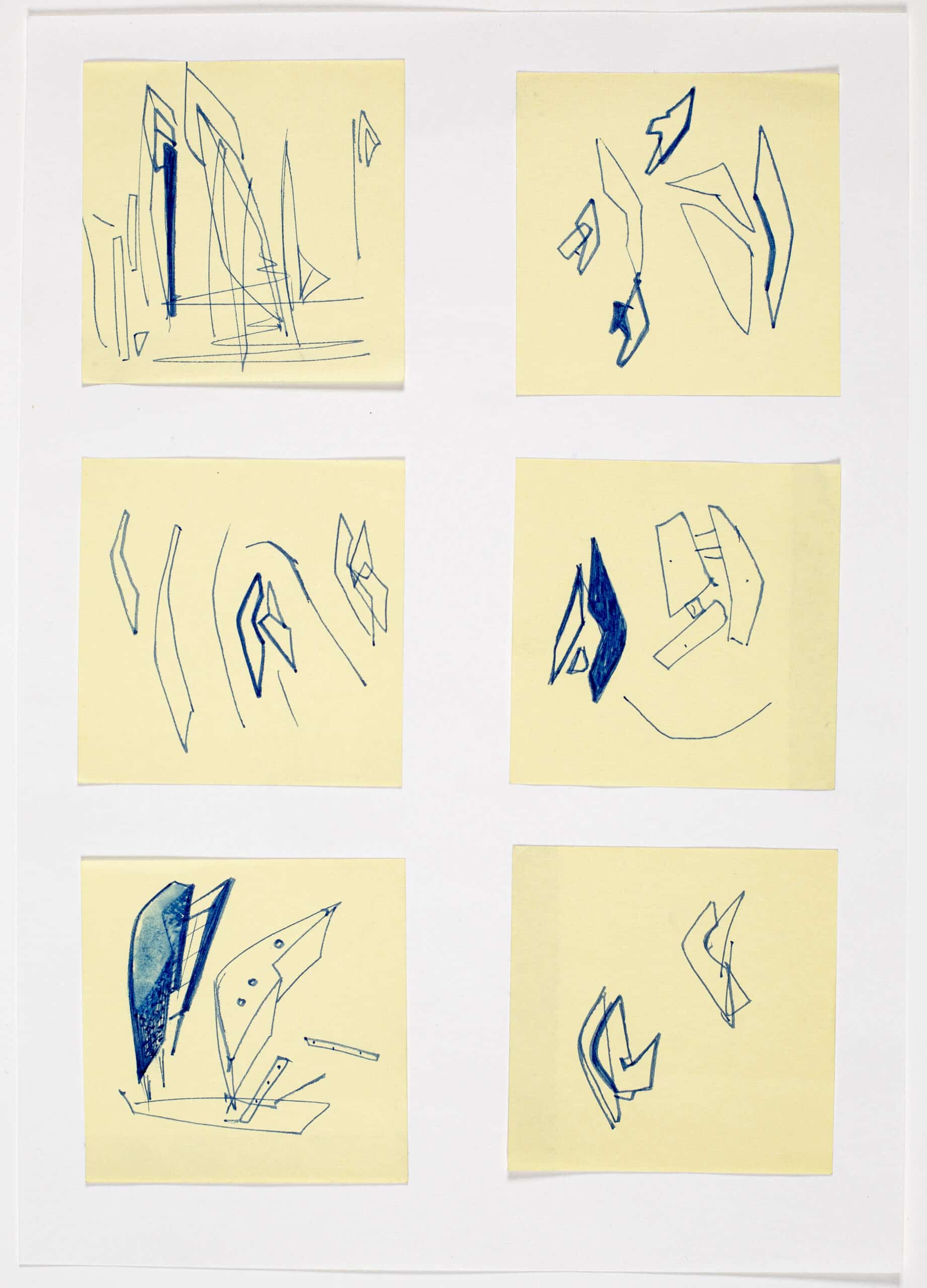

The evolution of the signature into an architectural writing marked a turning point in ZaHaDid’s practice. What began as an inquiry into selfhood soon became an operative instrument capable of generating spatial propositions. She entered a period of fragmentary experimentation in which the line was repeatedly tested, broken apart, and reassembled to form a vocabulary of emerging structures. The drawings from this phase—captured on Post-its, tracing paper scraps, and hastily gathered sheets—record the volatility of this transformation. On these intimate surfaces, the signature compresses, stretches, and tilts, never settling, always searching for spatial consequence.

This architectural writing eventually migrated beyond the scale of the building and toward the scale of the body. The same gestures that once organized circulation paths and structural spans reappeared as draping curves, folded planes, and tensile seams in her speculative studies for wearable forms. In these architectural-dress sketches, mass becomes surface, structure becomes contour, and the building envelope is reimagined with the intimacy of a garment.

Refusing the certainties of the construction market, ZaHaDid cultivated a practice defined by fluidity: a continuous migration from persona to signature, from writing to form, and from architecture to the scale of the body. Her legacy emerges from this deliberate instability, revealing a modernity rooted not in-built monuments but in the shifting, generative potential of the line itself.

She never died, she vanished.

— Charles Batach

*

‘Architecture; Buildings Have Woken Up’

Peter K.

Fifty years, ten exhibitions, and one book.

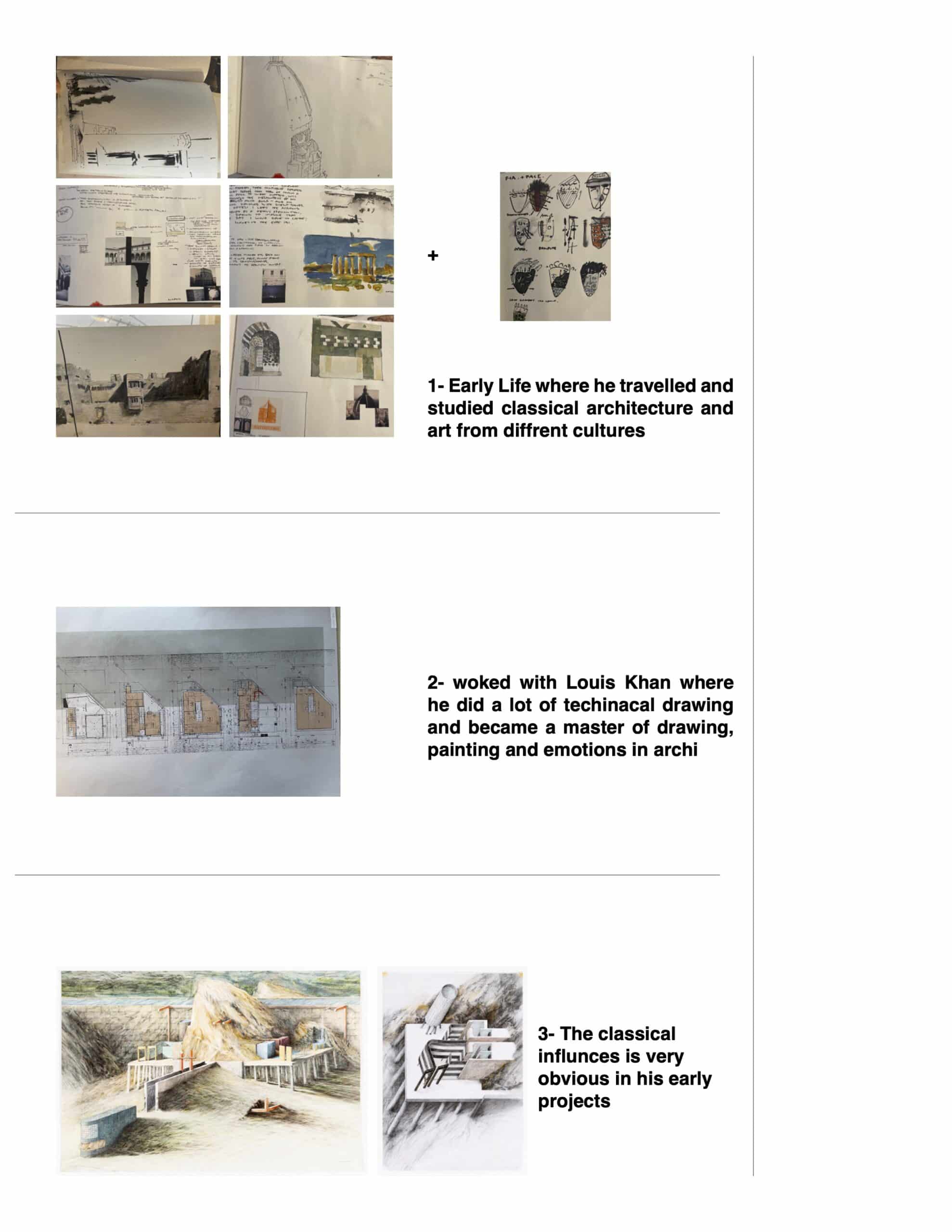

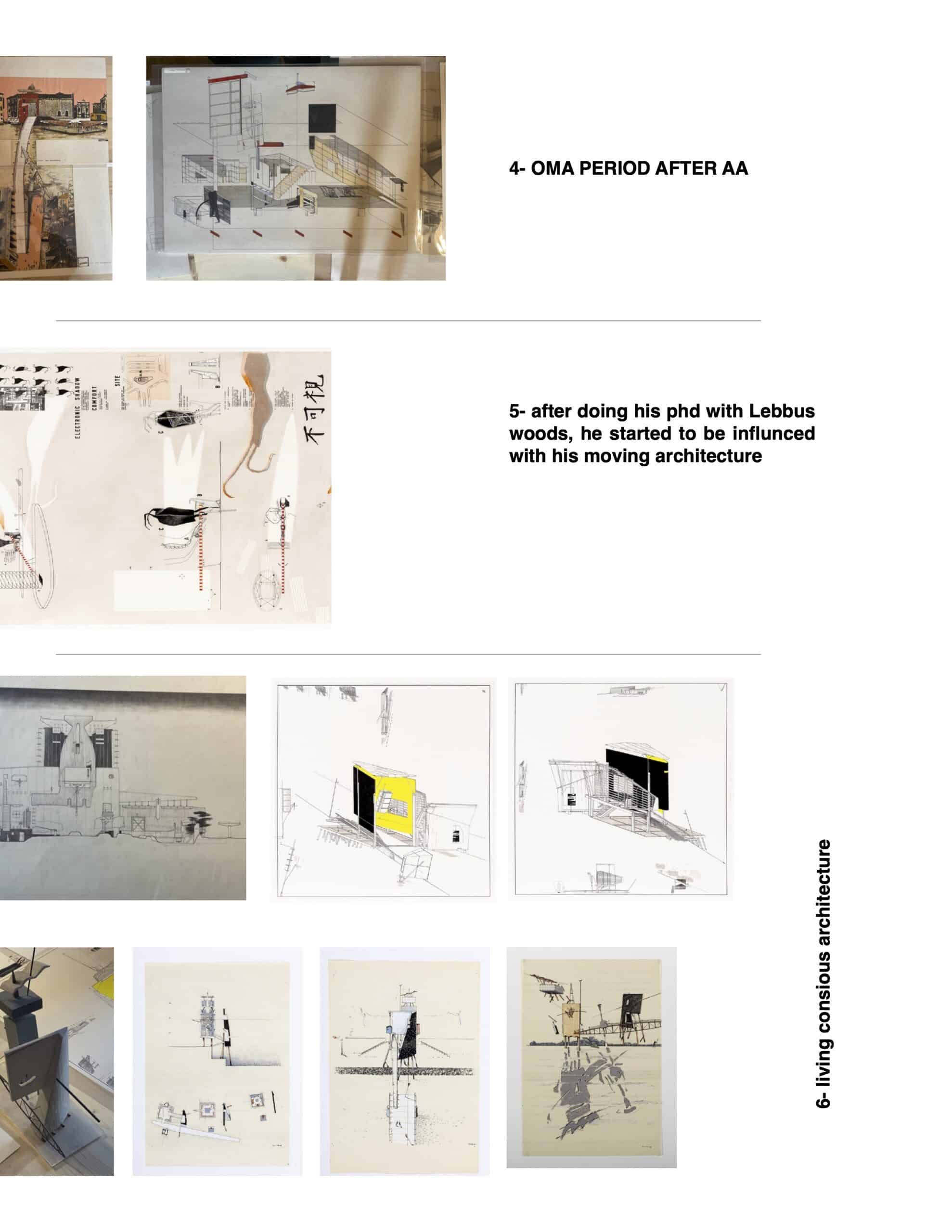

The visionary Spanish-American architect Peter K. awakened architecture as living creatures. He positioned himself between the metaphysical pursuit of idealised form and the ruptured nature of contemporary practice. Through a body of speculative drawings, he formulated Conscious Architecture, a framework that redefines buildings as evolving, sentient entities rather than static objects.

Born and raised in Spain, he experienced the architecture of Gaudí and the Alhambra at a young age—encounters that intrigued him. He joined Yale University in 1964, studying under Louis Kahn and, after graduating, working in his office for four formative years, where he absorbed a commitment to monumentality, form, and the intelligence of classical architecture. In 1972, Peter began roaming the world: studying ancient Egypt, Greece, and Italy, immersing himself in the art and architecture of multiple cultures. He spent much of this period drawing what he keenly observed. He eventually settled in London, working with various architects but remaining dissatisfied with the professional ethos of the period. In 1979, he joined the Architectural Association, where he encountered a different mode of thought through Rem Koolhaas—chaotic, contradictory, and unapologetically contemporary. Peter soon began teaching at the AA, developing his architectural ideas and visual language.

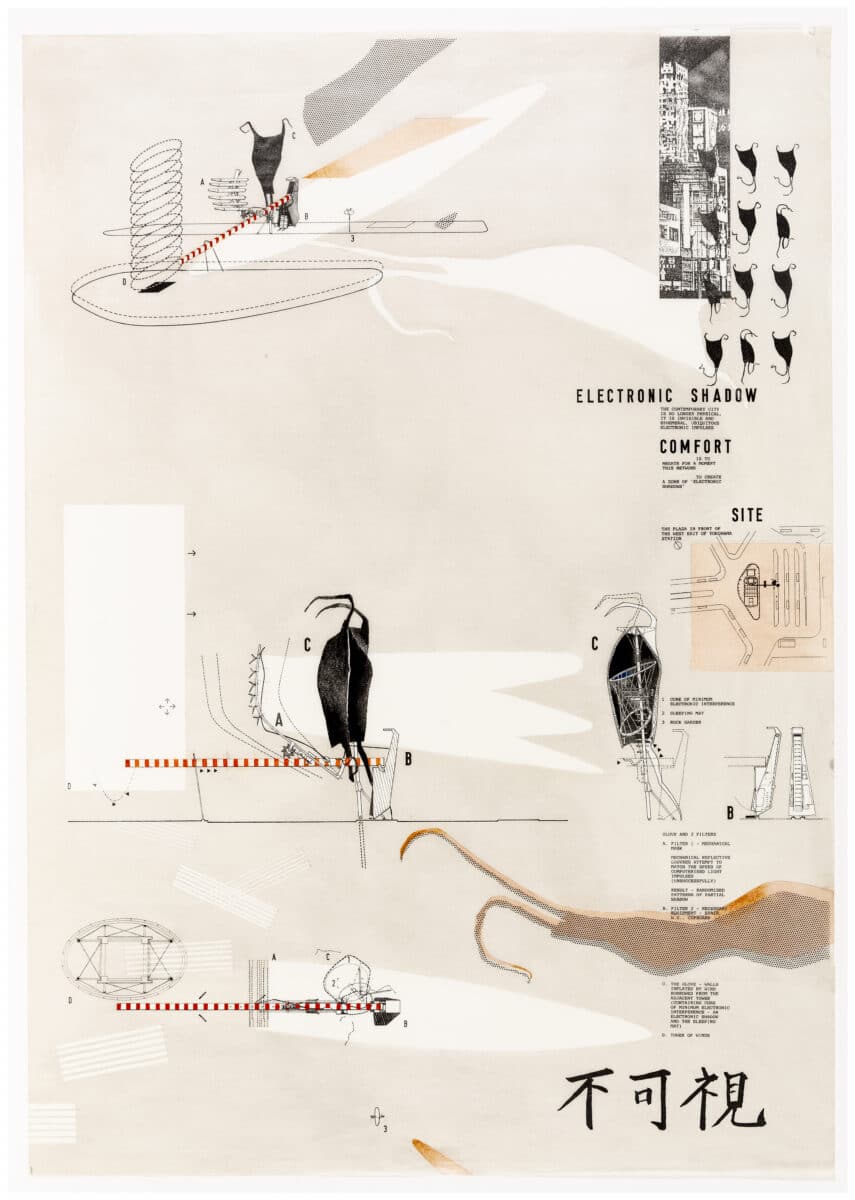

In 1988, he travelled to MoMA’s Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition, where the tension between Kahn’s monumental order and the deconstructivists’ deliberate instability pushed his thinking to a critical point. Around this time, he also became acquainted with the speculative worlds of Lebbeus Woods, whose work intrigued him deeply. Peter and Woods exchanged drawings, ideas, and had long philosophical discussions. Despite their different paths, both shared the intuition that architecture is more than objects.

Peter developed his thinking through the writing of Conscious Architecture, where he articulated an entirely new reality. His argument crystallised: architecture evolves, just as humans and technologies evolve, into living beings. He envisioned dwelling as a dialogue between two living entities: the human and the building. The book was published in 1992. Meanwhile, his radical seminars between Yale and the AA, along with his writings and drawings, gave him international visibility. The Guggenheim invited him for his first solo exhibition in 1993, followed by nine more exhibitions around the world.

The final irony of his life: just as he won his first built commission, he died before he could realise it. In the years that followed, his drawings circulated as intellectual documents rather than representations, shaping debates around deconstruction, posthumanism, and the ontology of the built environment. His entire legacy remained on paper, and yet proved more influential than many built works of his generation.

— Youssef Khobaiz

– Fabrizio Gallanti