Pan Scroll Zoom 12: Elizabeth Hatz

This is the twelfth in a series of texts edited by Fabrizio Gallanti on the challenges in the new world of online architectural teaching and, particularly, on the changing role of drawings in presentations and reviews. In this episode, Elizabeth Hatz discusses her personal experience of the pandemic and its consequences for her teaching studios at the School of Architecture, University of Limerick (SAUL), and KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm.

Next week I will get some goat’s parchment or vellum…

I have run out of seeds and fat for the birds. The studio needs a good cleaning out of stuff to liberate space for drawing and bricolage. The spring light is merciless.

Every moment without the screen is precious.

Peace, imagination, abstinence – and surprise.

Ireland

Before Covid-19, I left Stockholm almost every week, for 14 years, to see my students in the west of Ireland. Now: no travelling at all for one year. I have not yet met my current students, we have only ‘met’ on the screen.

Strangely, that is also true for a new, very special architecture friend – deeply special indeed – with whom I feel a very particular affinity, inexplicable and irresistible.

But I do not think we would have ‘met’ unless the first encounter was physical – with the work.

Francesca Torzo’s exhibition in the Arsenal at the 2018 Venice Biennale swept me off my feet. It turned out that she, in parallel, had developed an interest in mine, in the Central Pavilion, a celebration of the architectural drawing, called Line, Light, Locus.

Thus started a conversation online and by email, followed by mutually guest reviewing our students’ work, giving lectures and exchanging thoughts, drawings, encouragement and inspiration.

I would ‘visit’ her office in Genoa, see her wonderful textiles, her chairs and designs.

For conveying architecture and enlightening her surrounding, Torzo is exceptional. It feels as if I have known her for centuries, the encounter corresponding to the same self-evident and immediate attraction as to Sumerian Mastabas or wildflowers. Such a surprise it is there – it has always been there.

Something picked up about focus…

Such relief not to travel, to escape planes, airports, underground trains, conveyer belts, escalators and buses – spaces with, as sole fixed point, the mobile phone, or – at best – a good book or some Bach in the earphones. Heaven to slow down.

BUT

missing Ireland.

Miss my students, colleagues, friends, strangers…

Miss the tactile experience of wet stone, horizontal rain and gentle dialects.

Sharing architectural encounters can never be substituted by anything else.

A glass of Guinness at Locke’s Bar or Tom Collins can never be substituted by anything else. Never.

However, the longing might help shape the imagining.

Apparently, Hawksmoor never left England, he visited art and architecture in books, just like Morandi, who barely left his studio but devoured art images in only black and white, getting exceptionally sensitive to shades and luminance. Deprivation provokes painfully creative compensational acts.

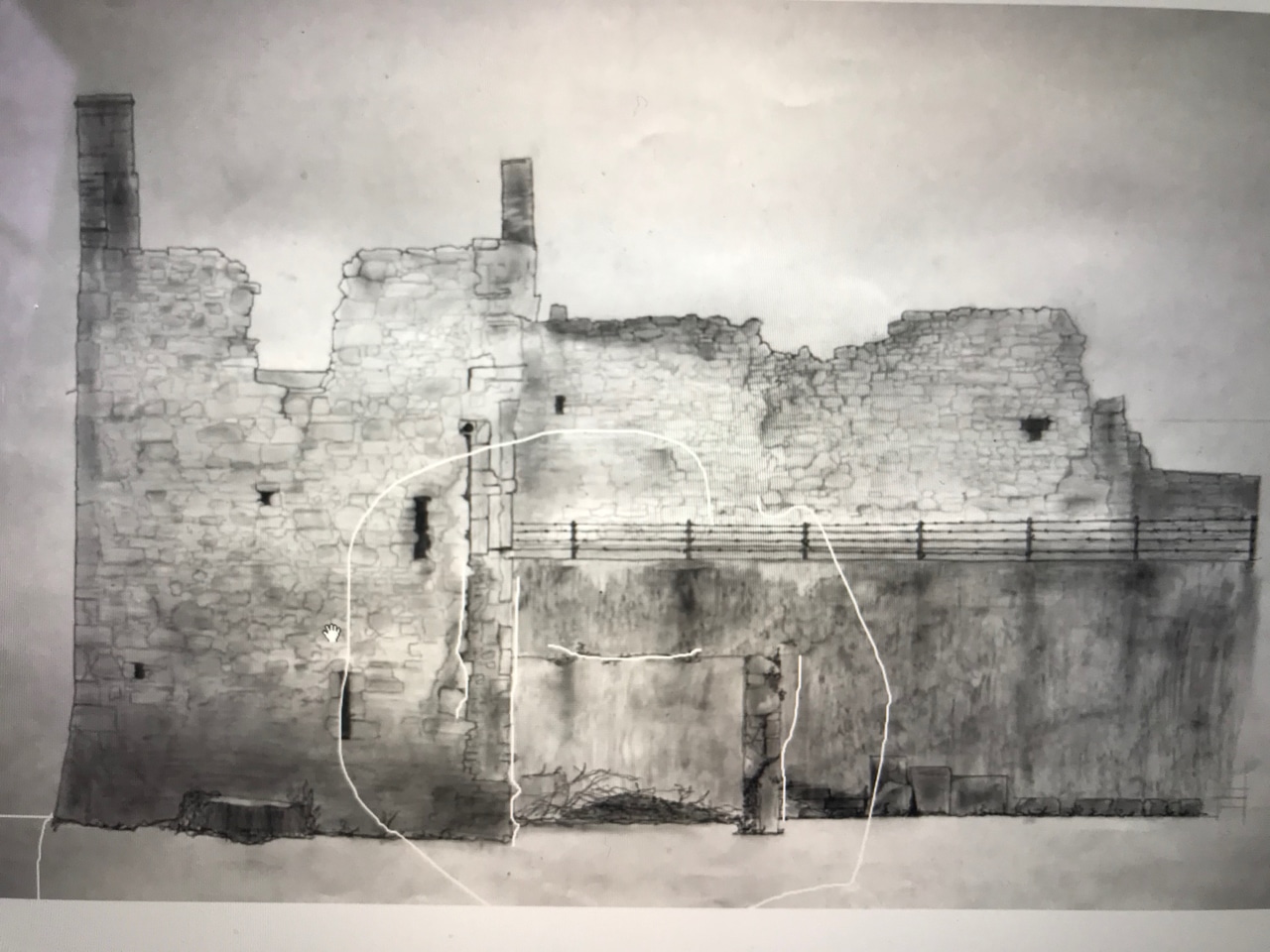

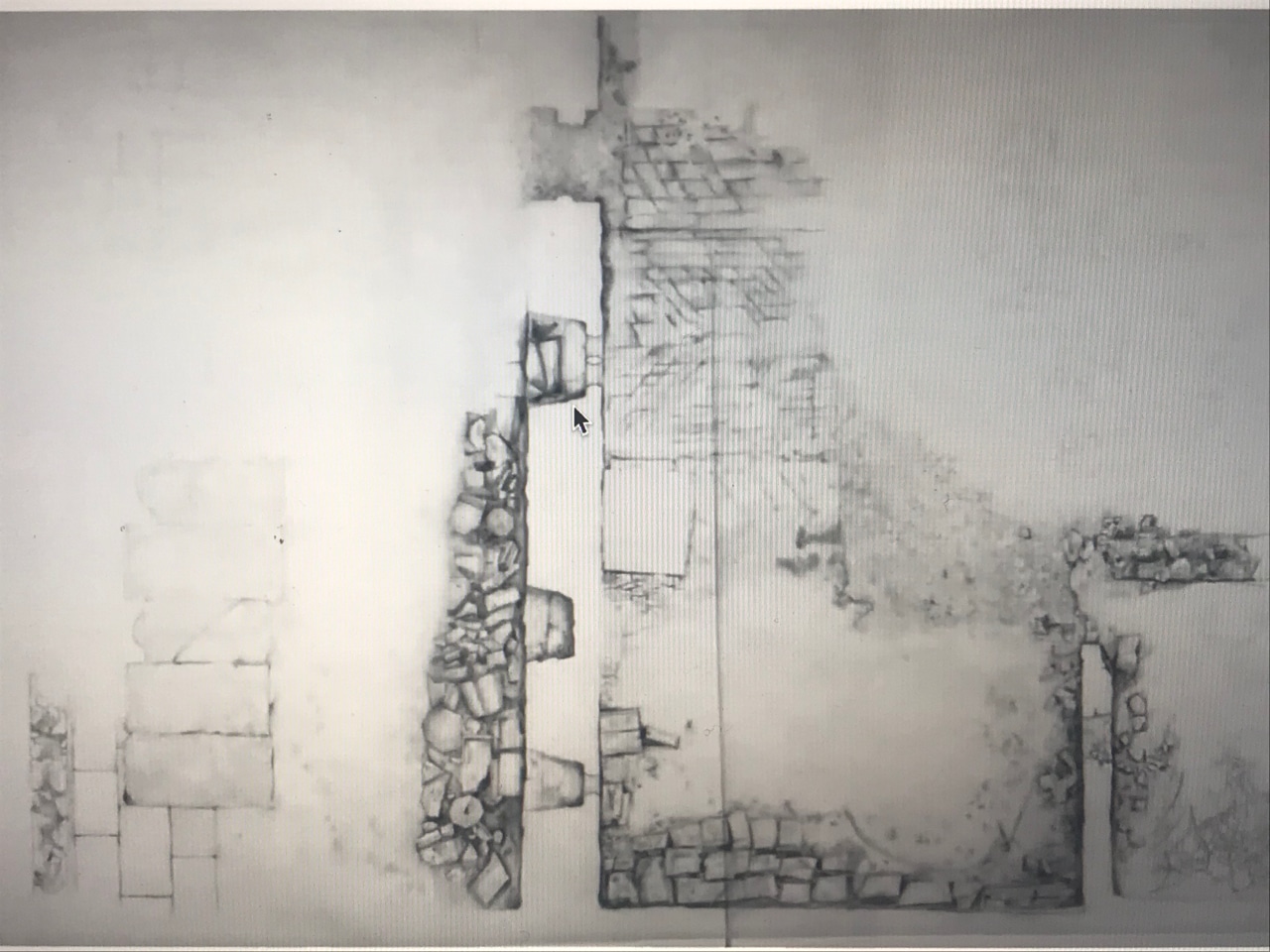

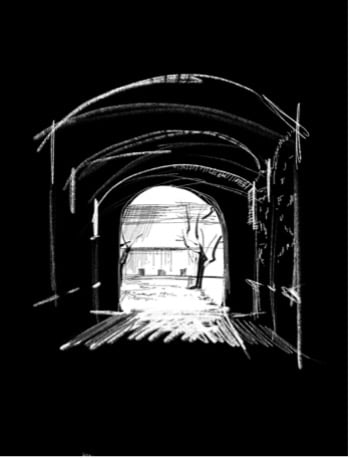

Not investigating a site with my students is hard, sketching with them on site, commenting their drawings on site, touching the stones, measuring, discovering together.

Not sitting with them at the desk sketching on tracing, capturing a faint hesitation and allowing silence to bring it into searching, meek pencil strokes.

Losing the weight of lines, the tacit space between them, that silent conversation – sad absence.

Nothing can ever replace that.

I am not going to downplay the loss created by this absence.

I will never pretend we can get used to a digital form of teaching, which will be equally rich, mysterious and complex.

Because it will never be.

On the contrary, I am more than ever convinced that loving and learning architecture – or the world at all – relies on being there, together, experiencing and conversing in the physical room, in situ. Feeling the light fading, together.

Architecture demands presence and commitment, an encounter in dialogue. This dialogue is also crucial between students, not to mention the knowledge picked up in the studio: a glimpse of a peer’s desk, at the corner of the eye, eavesdropping on a conversation, the silent energy conveyed by the sheer presence of working comrades around you.

For my own work the splendid isolation may be balsamic peace to regain focus by returning to quiet thoughts, books, drawing and very simple delights. Time abandoned and obliterated. Wonderful.

For young students it is different.

Over time it probably makes you unmotivated, lazy, neutralised…

Frustration and boredom can do wonders. And terrible things.

Spring 2020: SAUL, Ireland – Teaching with Ger Carty

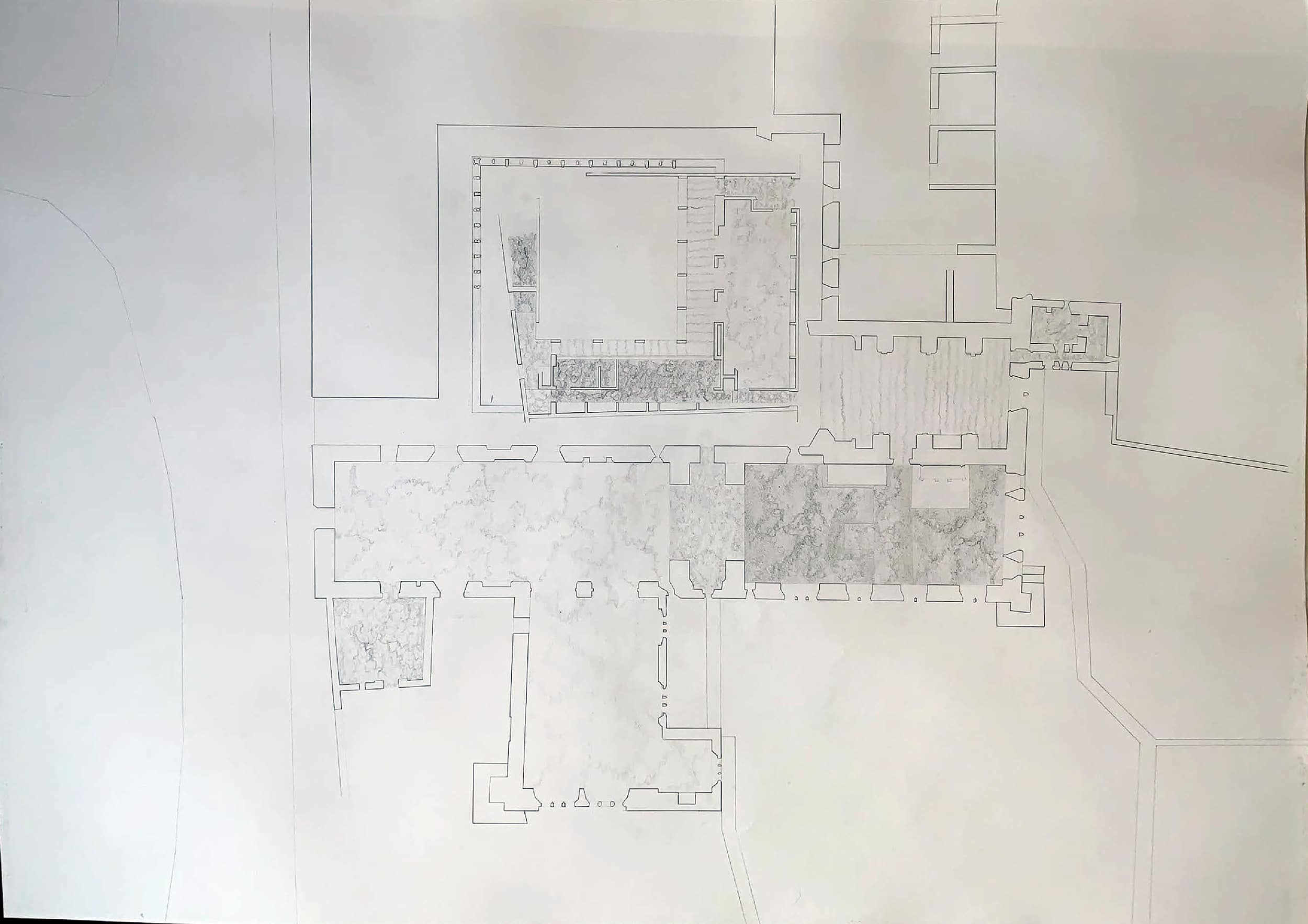

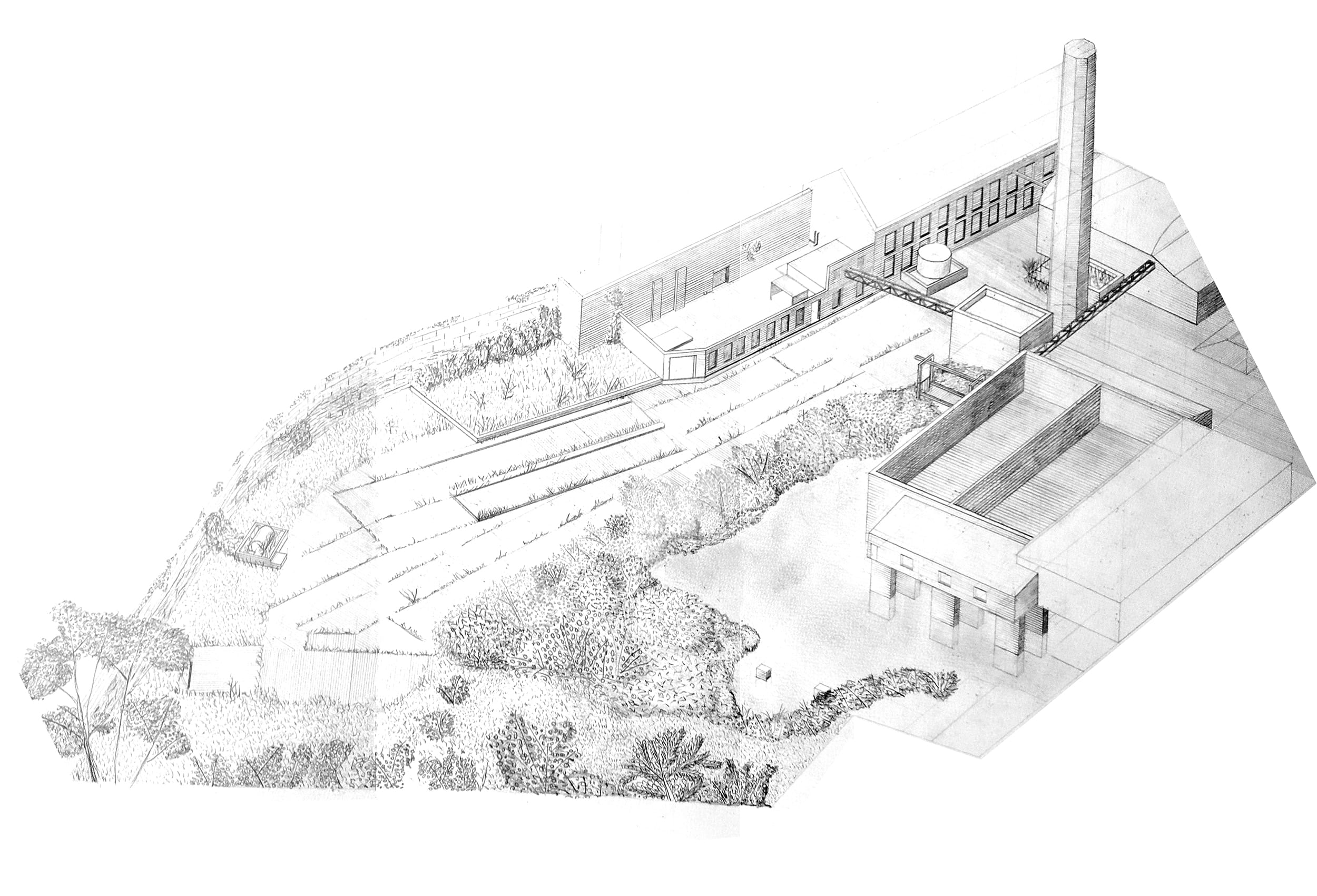

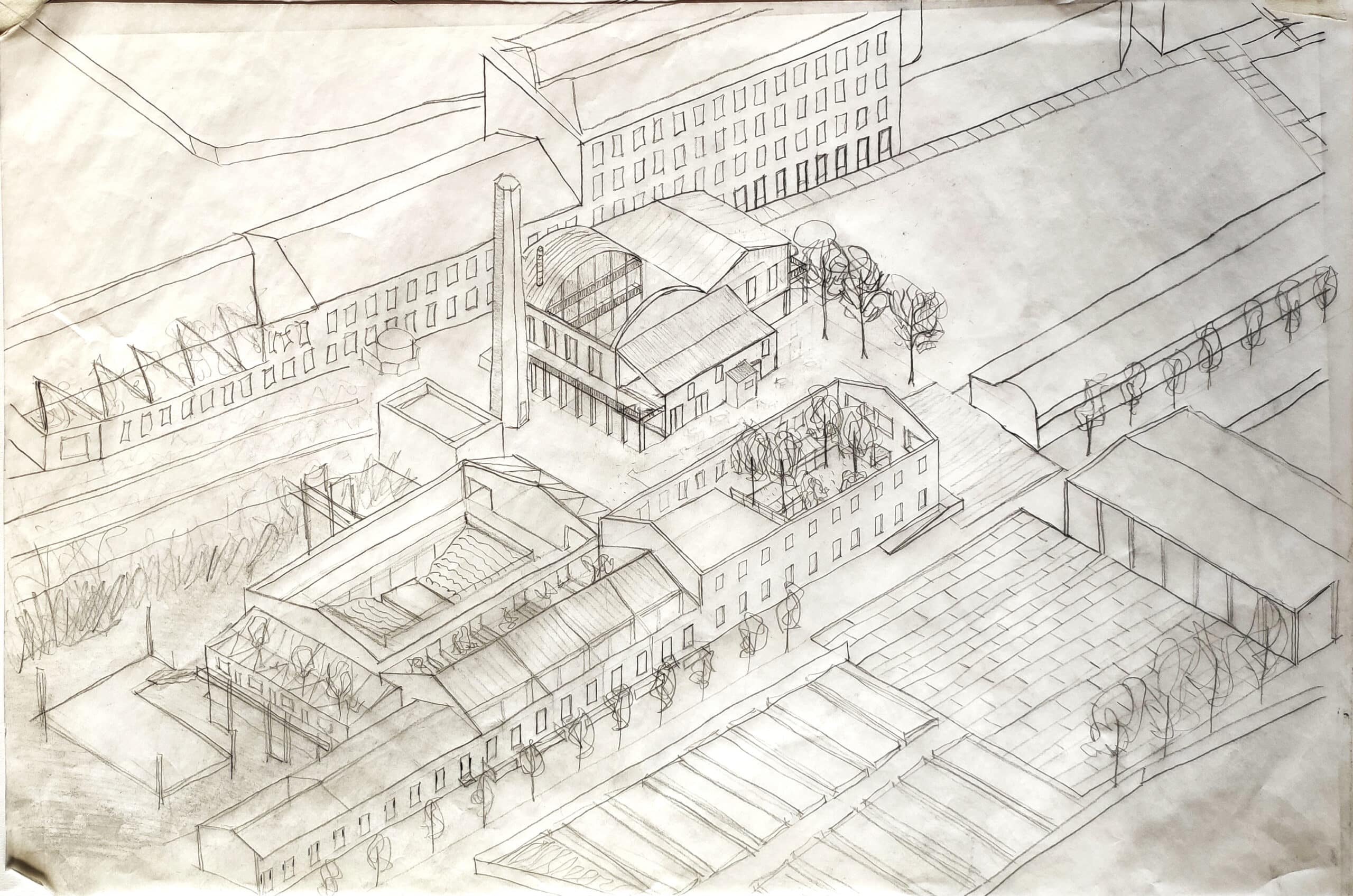

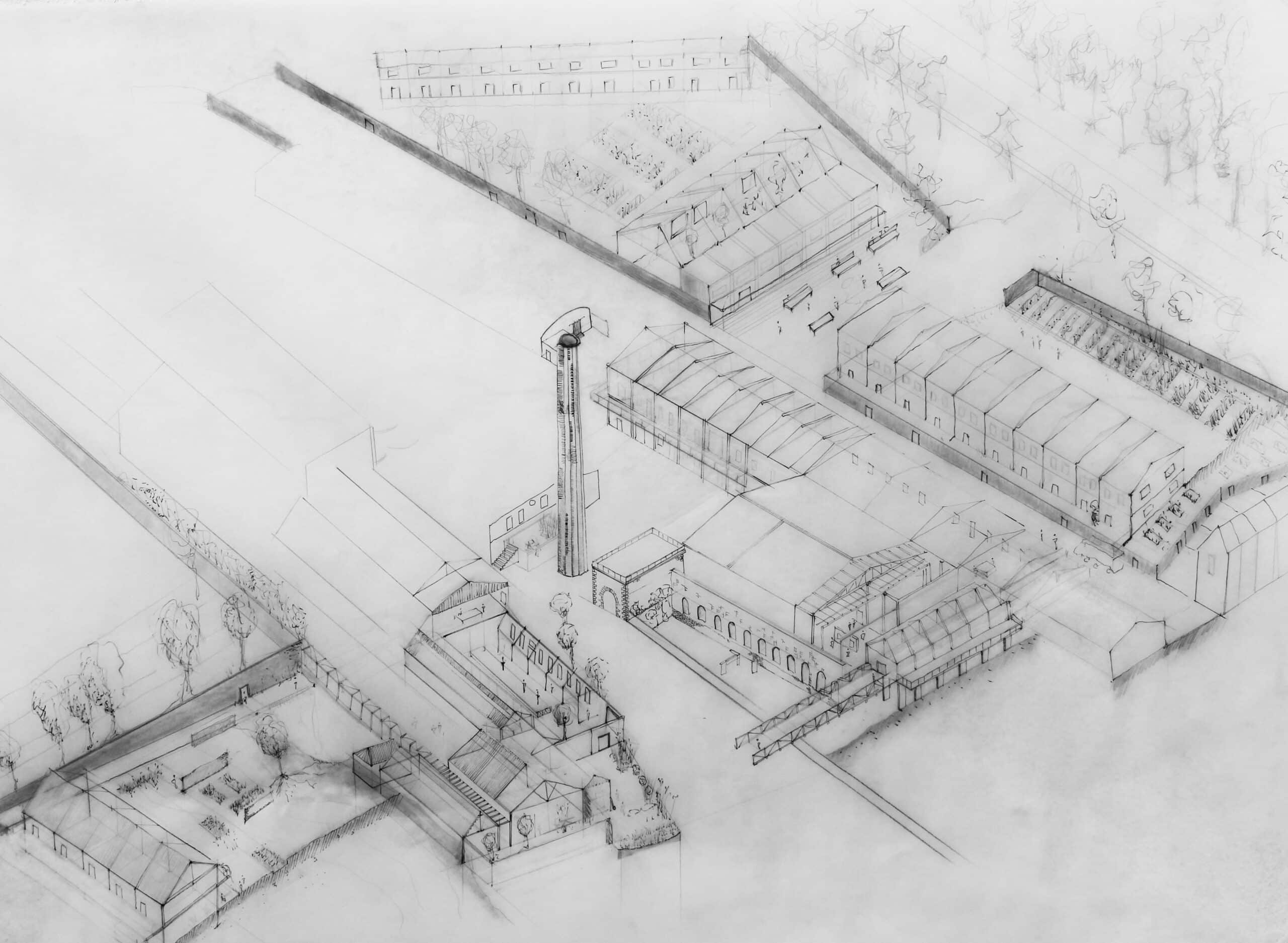

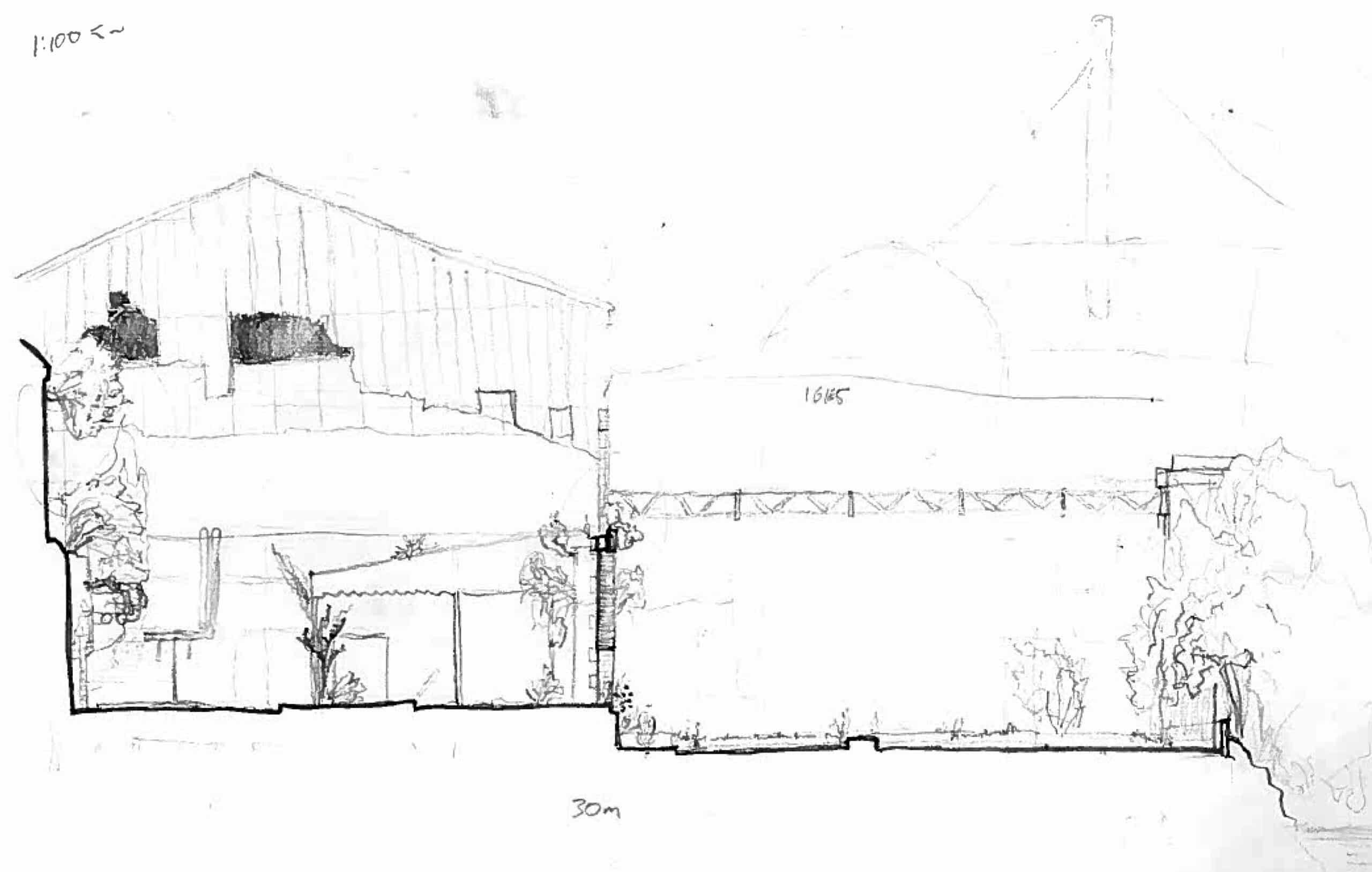

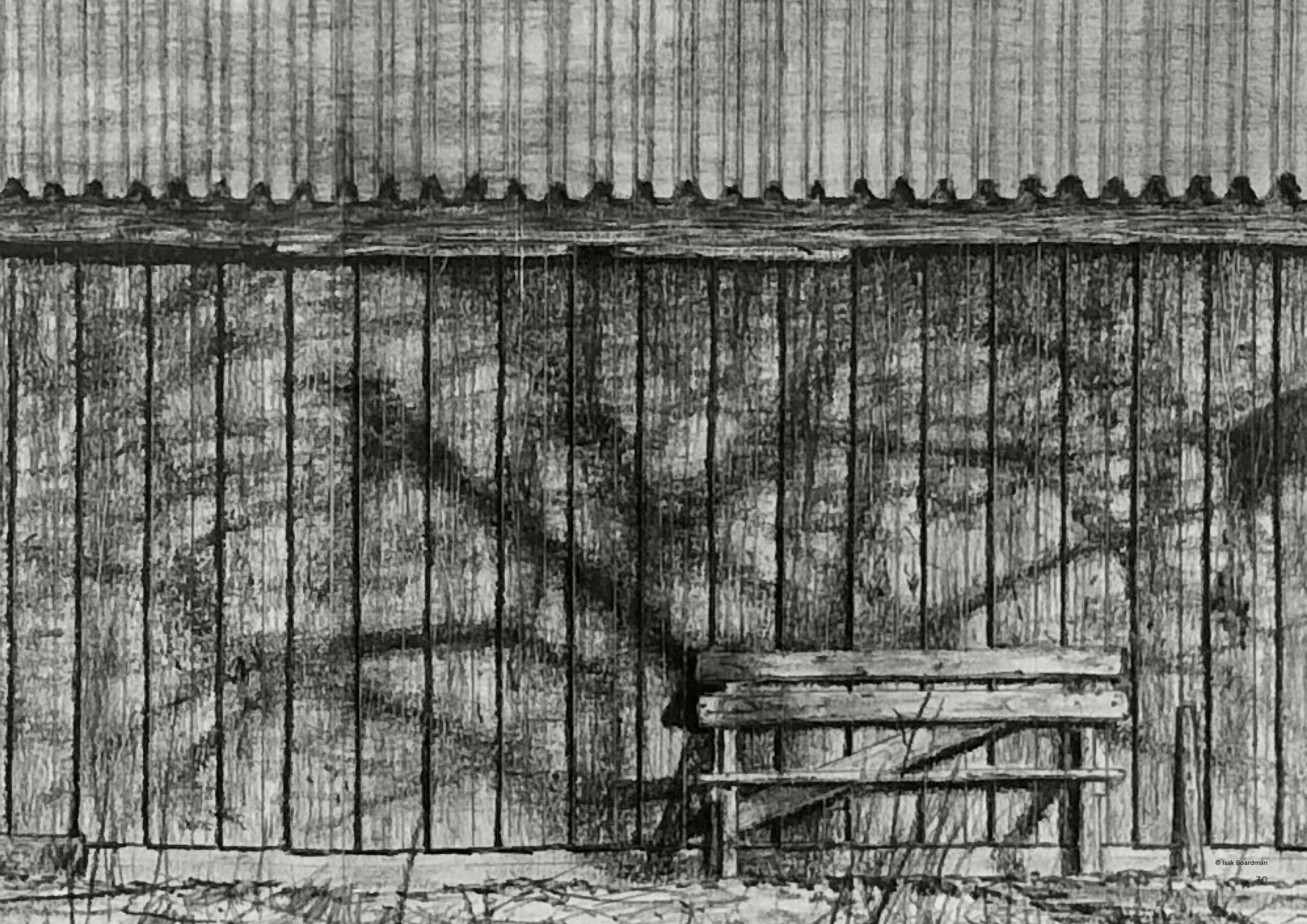

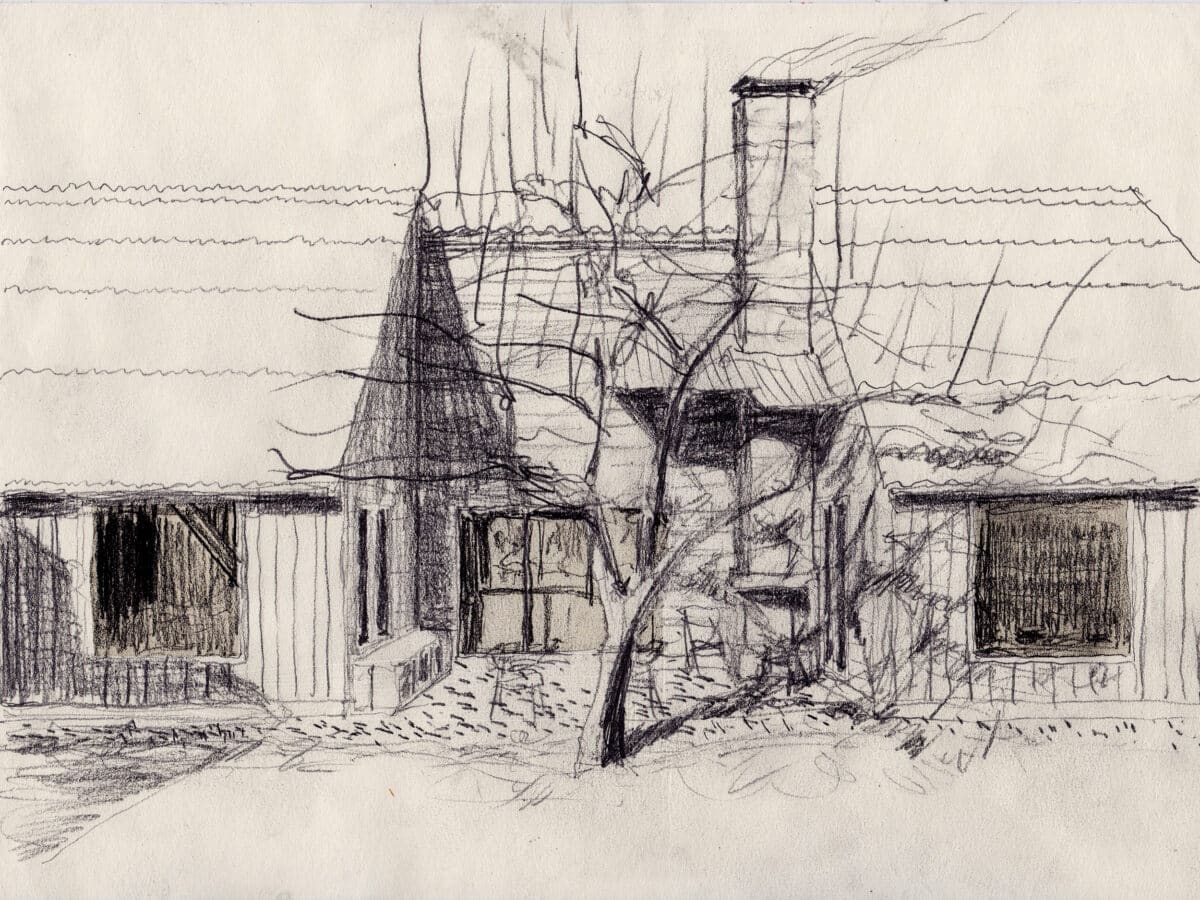

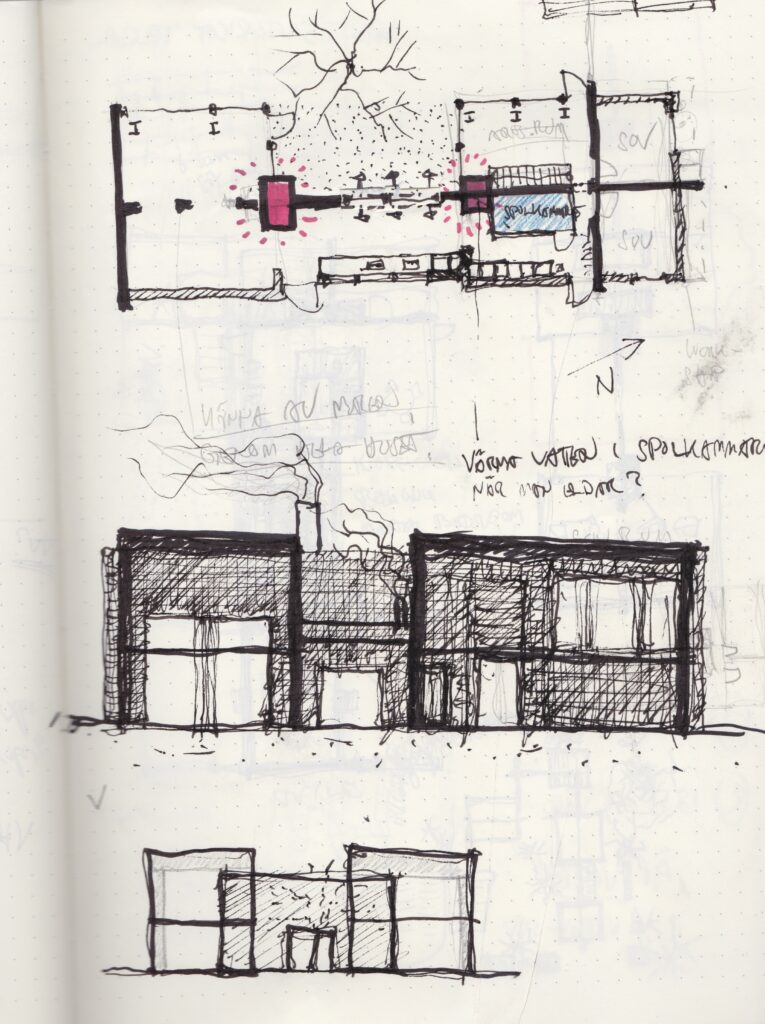

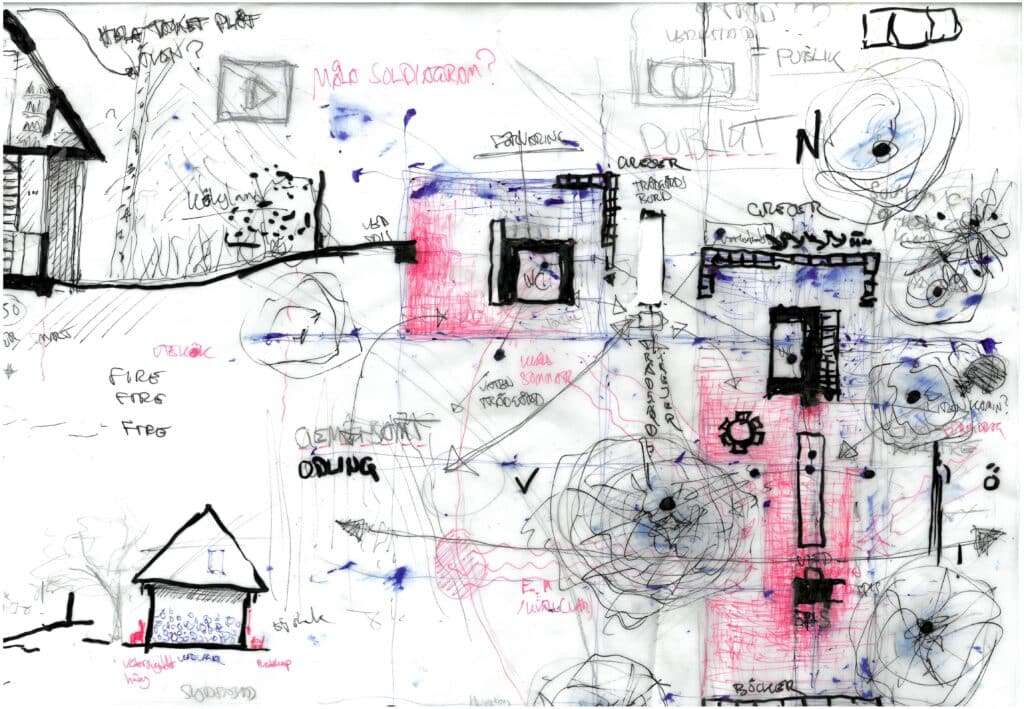

We have been to Shatwell Farm already in the autumn, we have sketched at length and know each other well when the pandemic strikes. We are working in Limerick on an amazing abandoned industrial site with a flax factory built from the limestone quarried on the site: one side carved deep, the other piled high. Drawing, drawing, drawing…

Inventive and obsessive appropriation of the site through drawing are the hallmarks of the studio.

An observation in emotion and yet doggedly open to all sorts of detail, embracing the nature of the place in the widest sense of the notion. Particular, peculiar, registering attentively, while making decisions, intuitively, rationally, irrationally…

‘[…] From this point of vulnerability, the yard begins to become inhabited by a filigree of small scale installations that penetrate the wall and ground. An order could be created in the space here through a similar language of lean-to or matrix-like webs of structure which can allow for individual inhabitance and development. These can be assembled using materials found on other parts of the site or left over from the stripping back of buildings, and can be temporary and variable in form depending on their use and condition.[…]’ (Luke Roberts, SAUL 4th Year student)

We make the students take on an enormous and very complex site, down to detail. They pull it off!

Spring 2020: KTH, Stockholm, Sweden

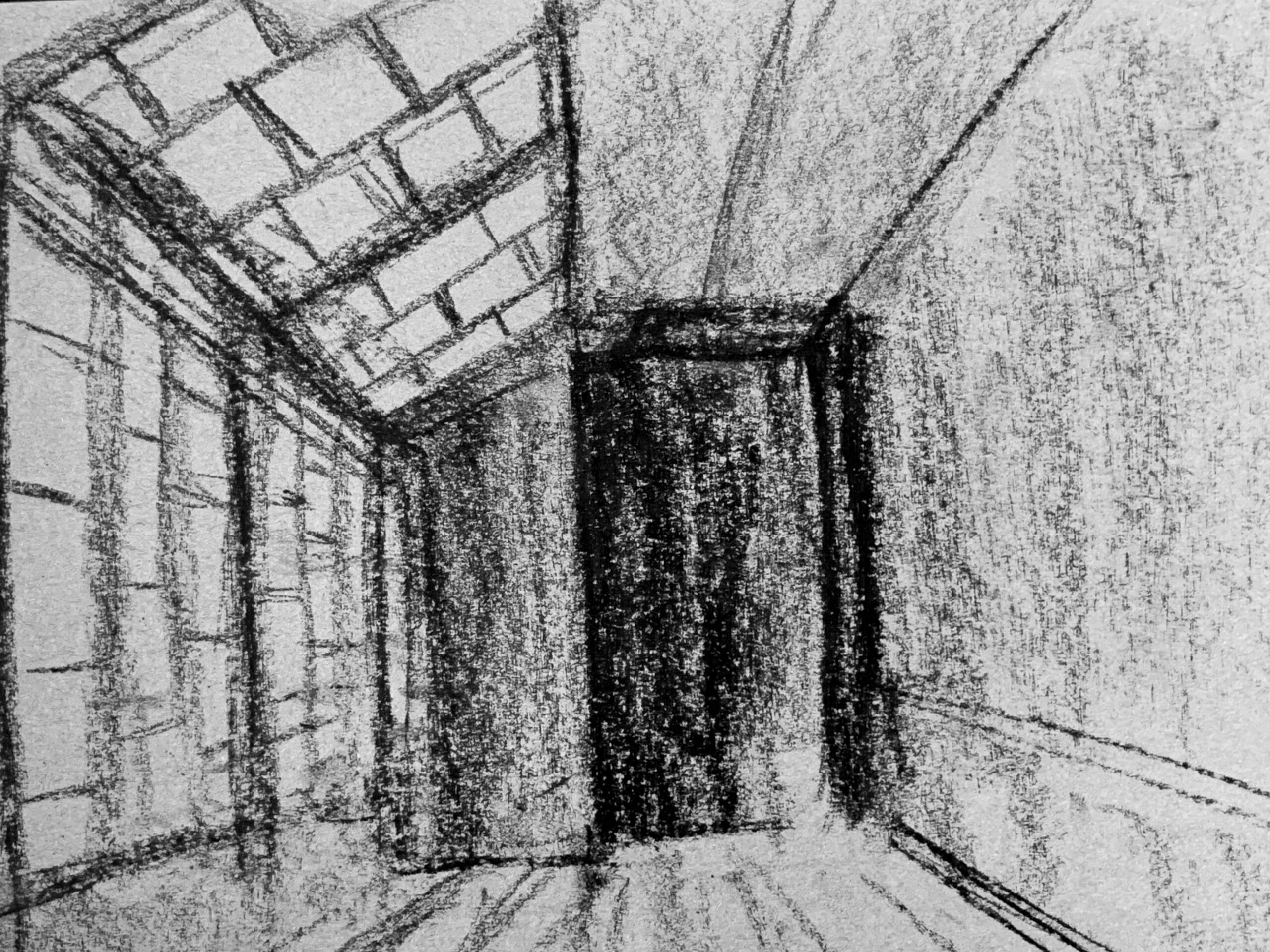

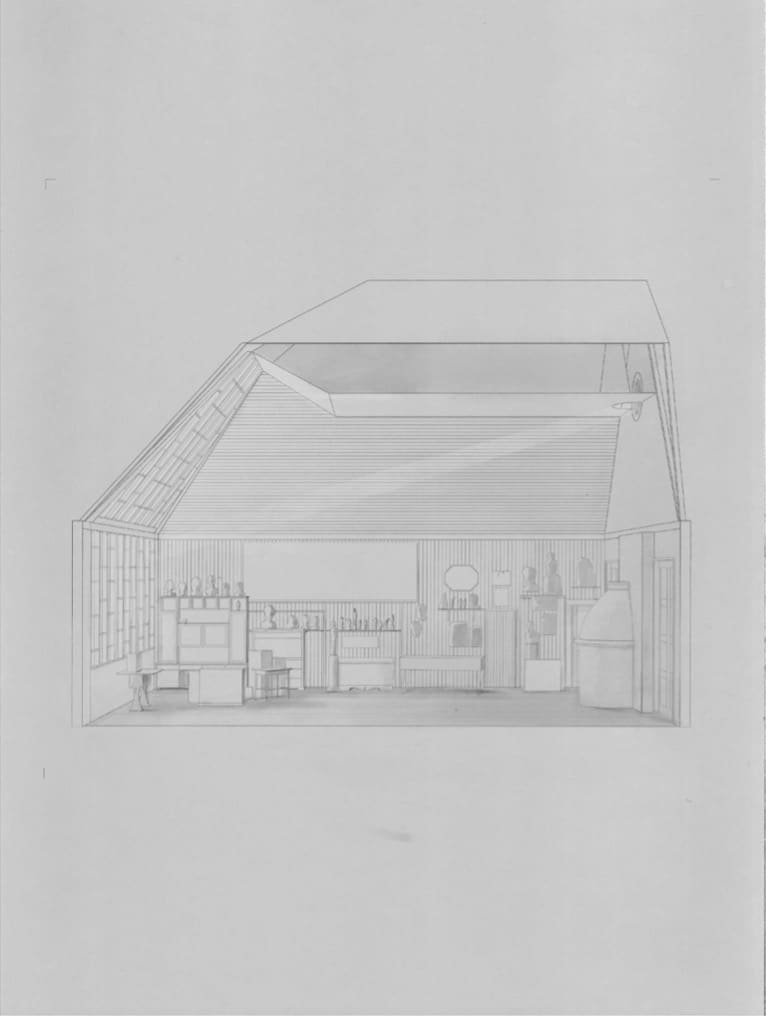

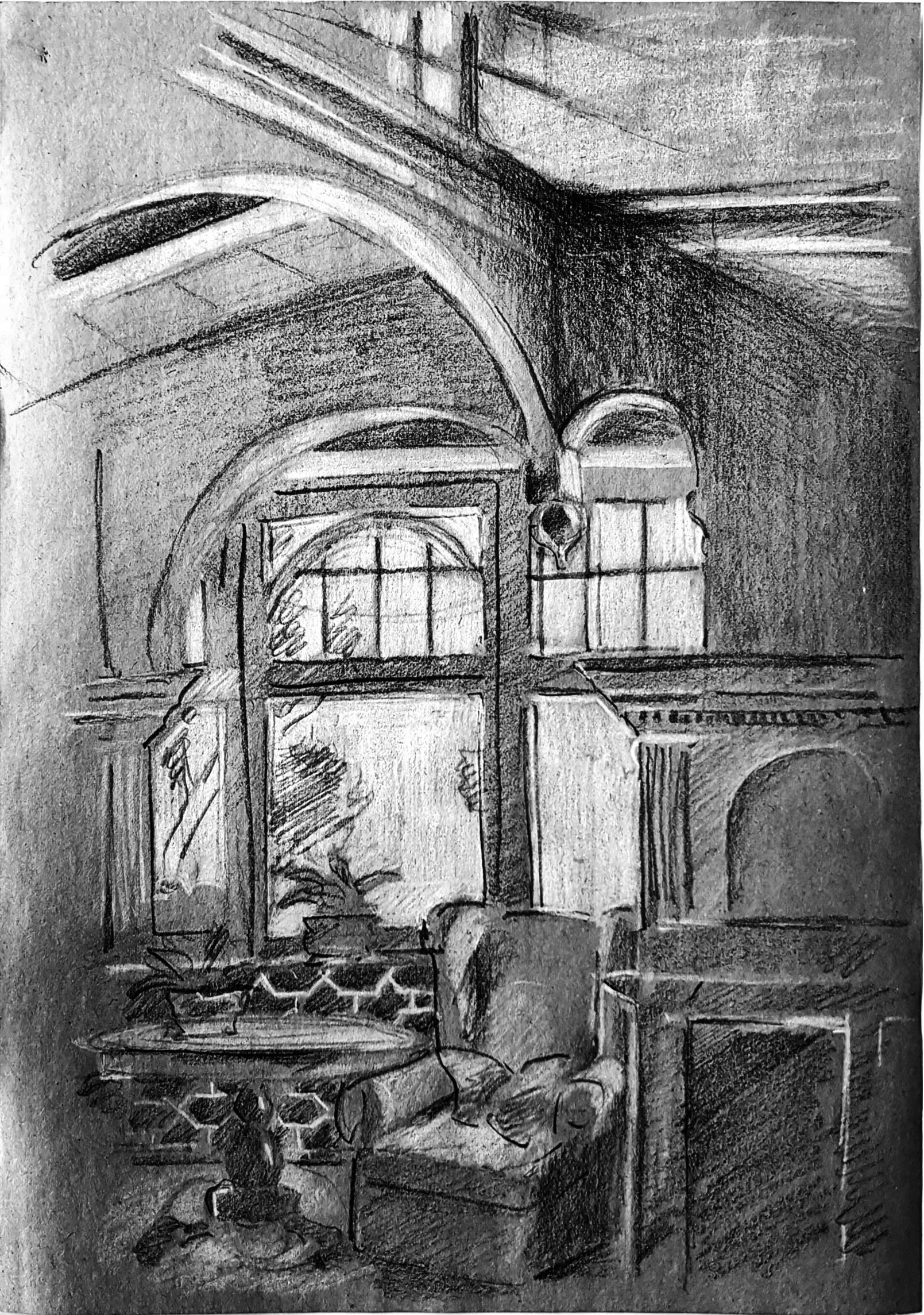

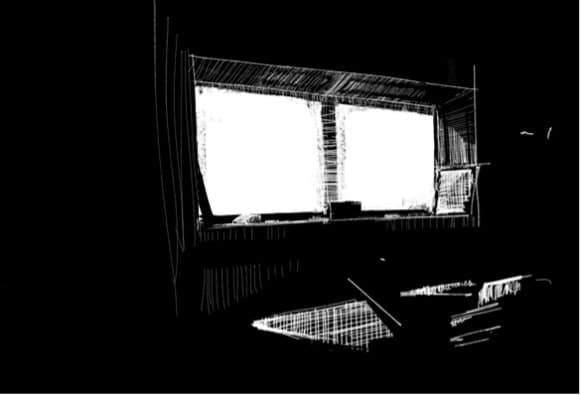

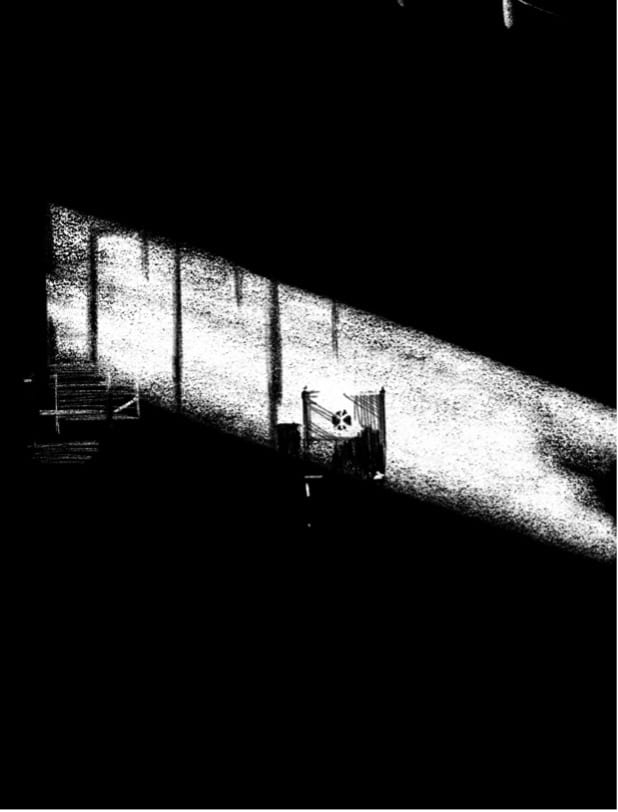

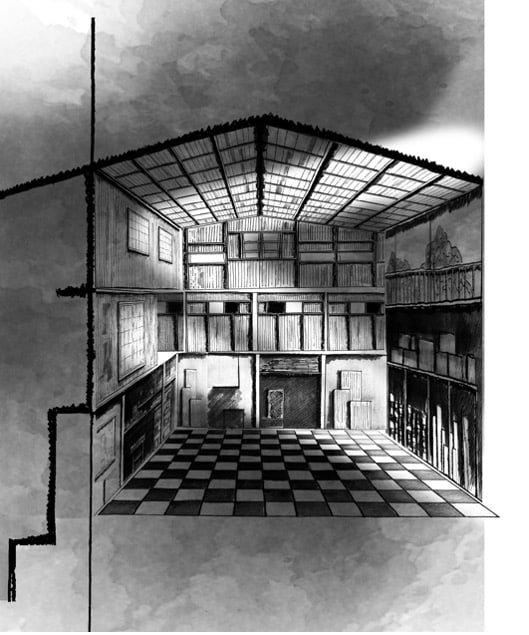

Bedside the thesis students, my elective is running – ‘Recycling Rooms’. We begin before the pandemic, spending hours on end in selected rooms, drawing light as carved out of darkness, obsessively, in silence. We could stay forever. Students say this is unique in their education – the sheer time they are offered…

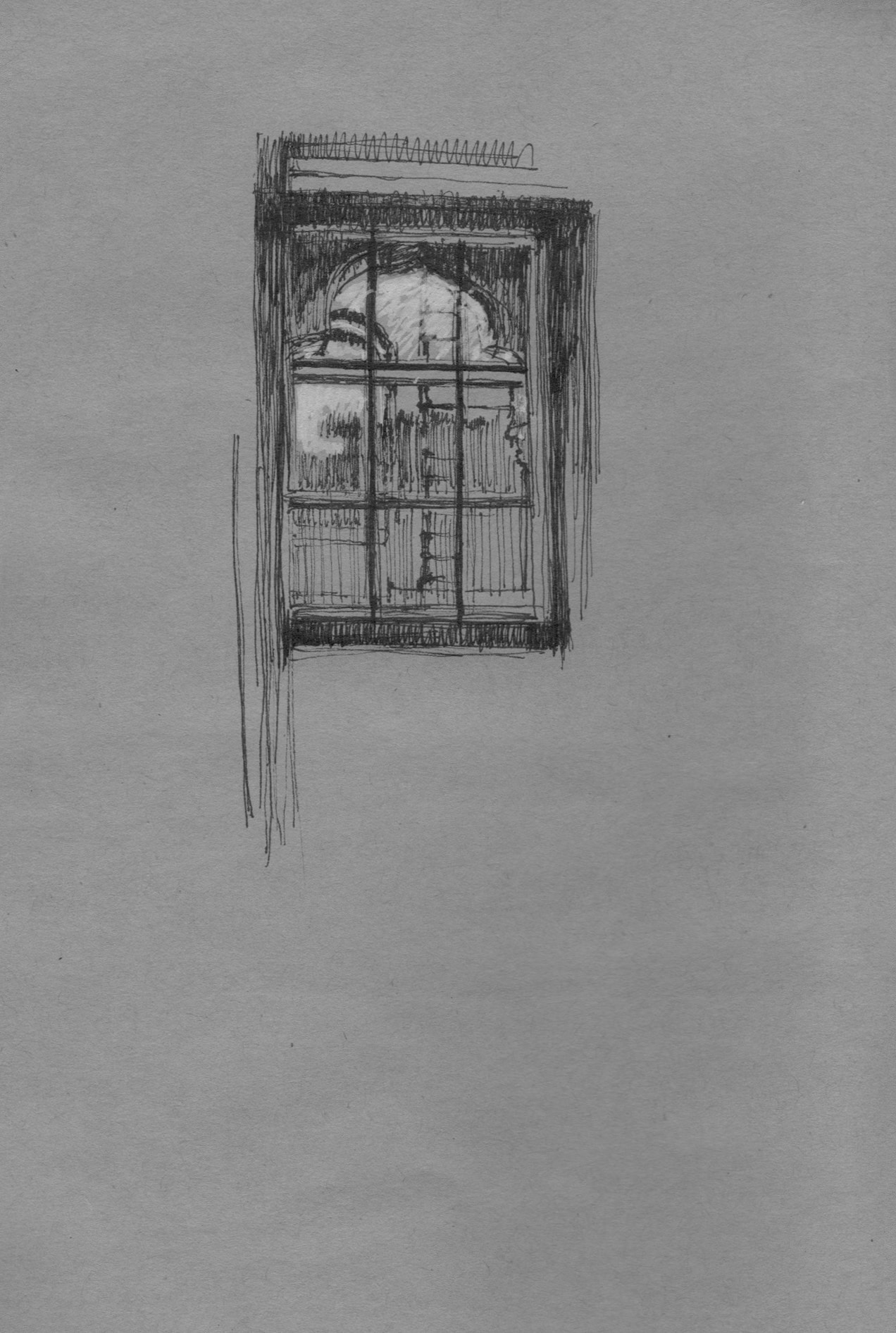

Sketching at Carl Eldh’s studio by Ragnar Östberg, in Stockholm.

The abstracted form of smooth plaster; no difference between hair and skin, between clothing and skin, both light and shadow are given a blank canvas to play upon, changing surfaces from grey, to white, to black, to grey throughout the day. And as the light and the shadow dance across their smooth sculpted bodies, their expressions begin to do the same. The light embraces the sculptures and their expression embrace the space. The poetry of light expresses the human dignity, brought forth by the architecture of the space. (Julia Thiem, KTH student)

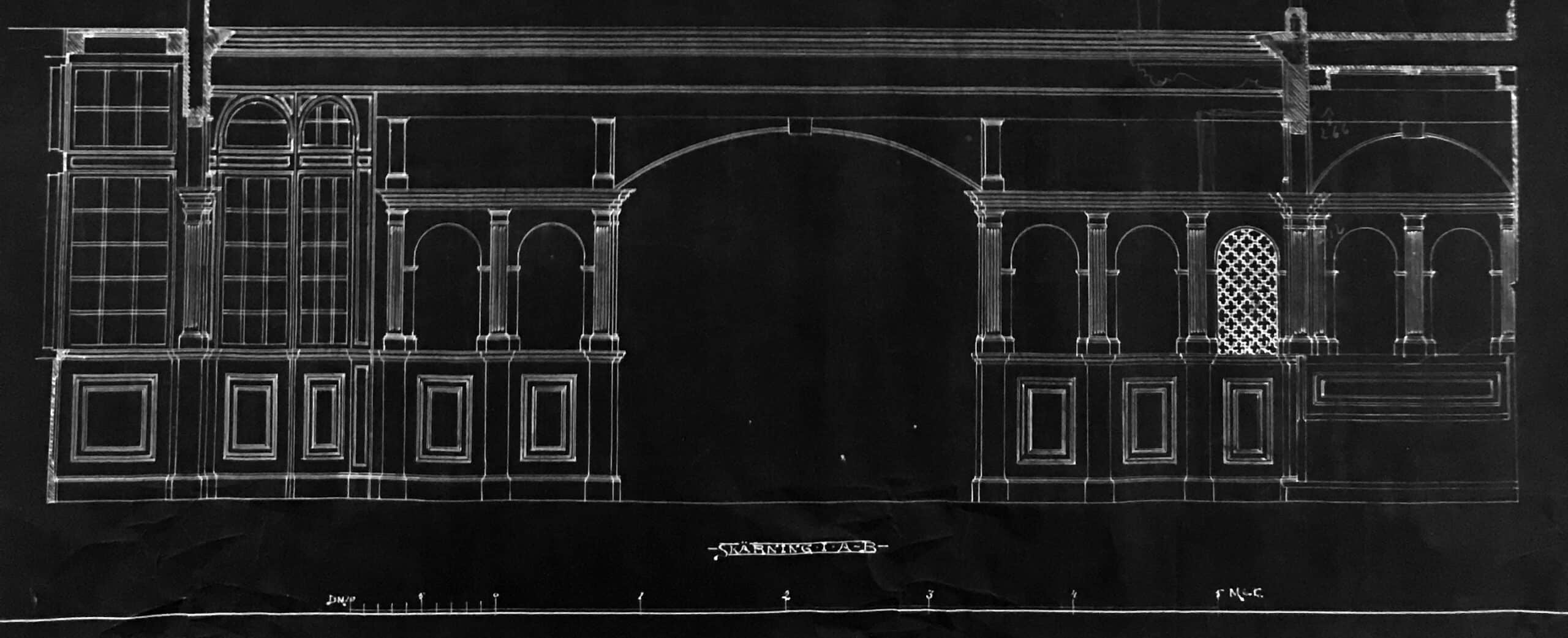

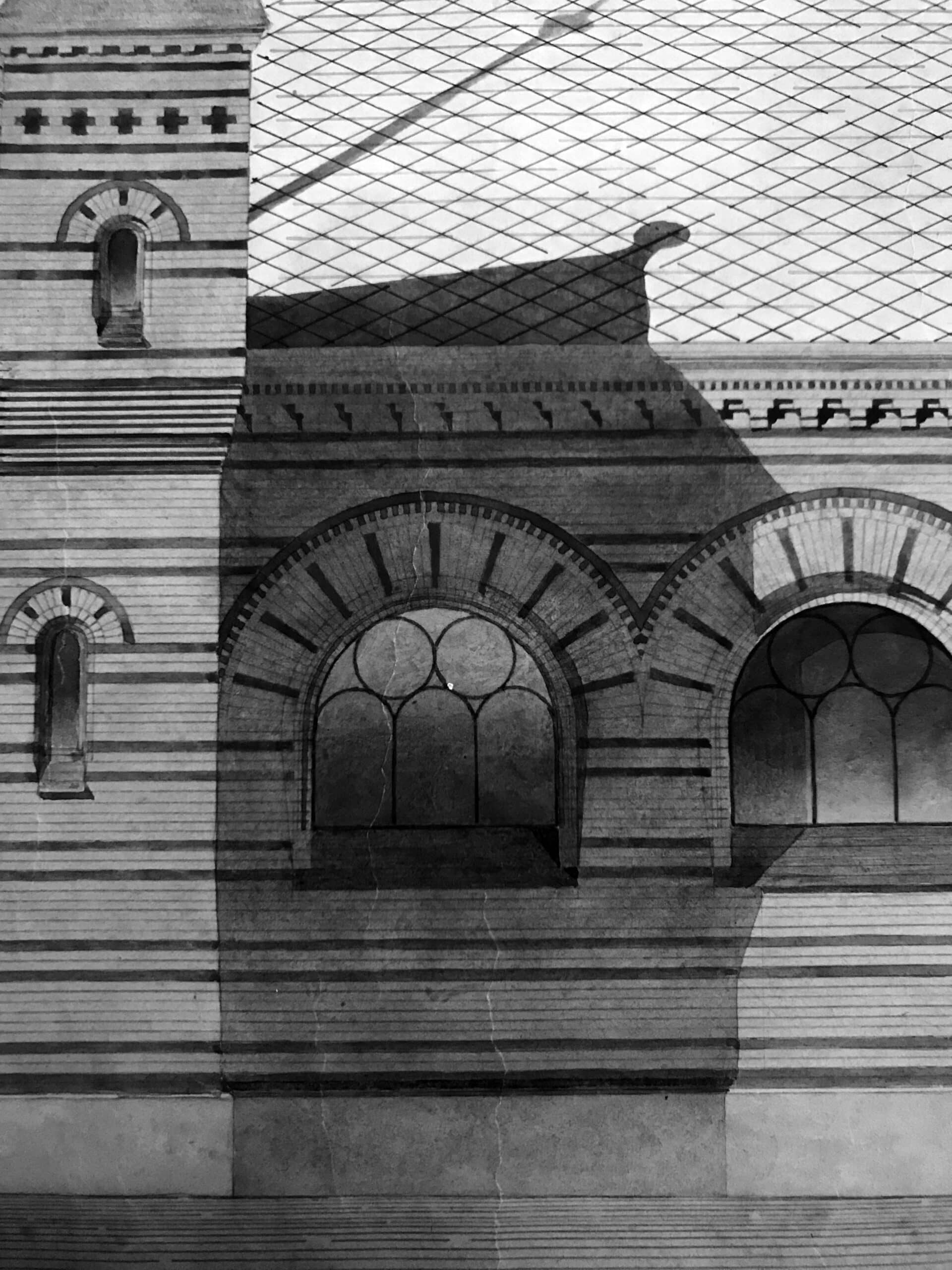

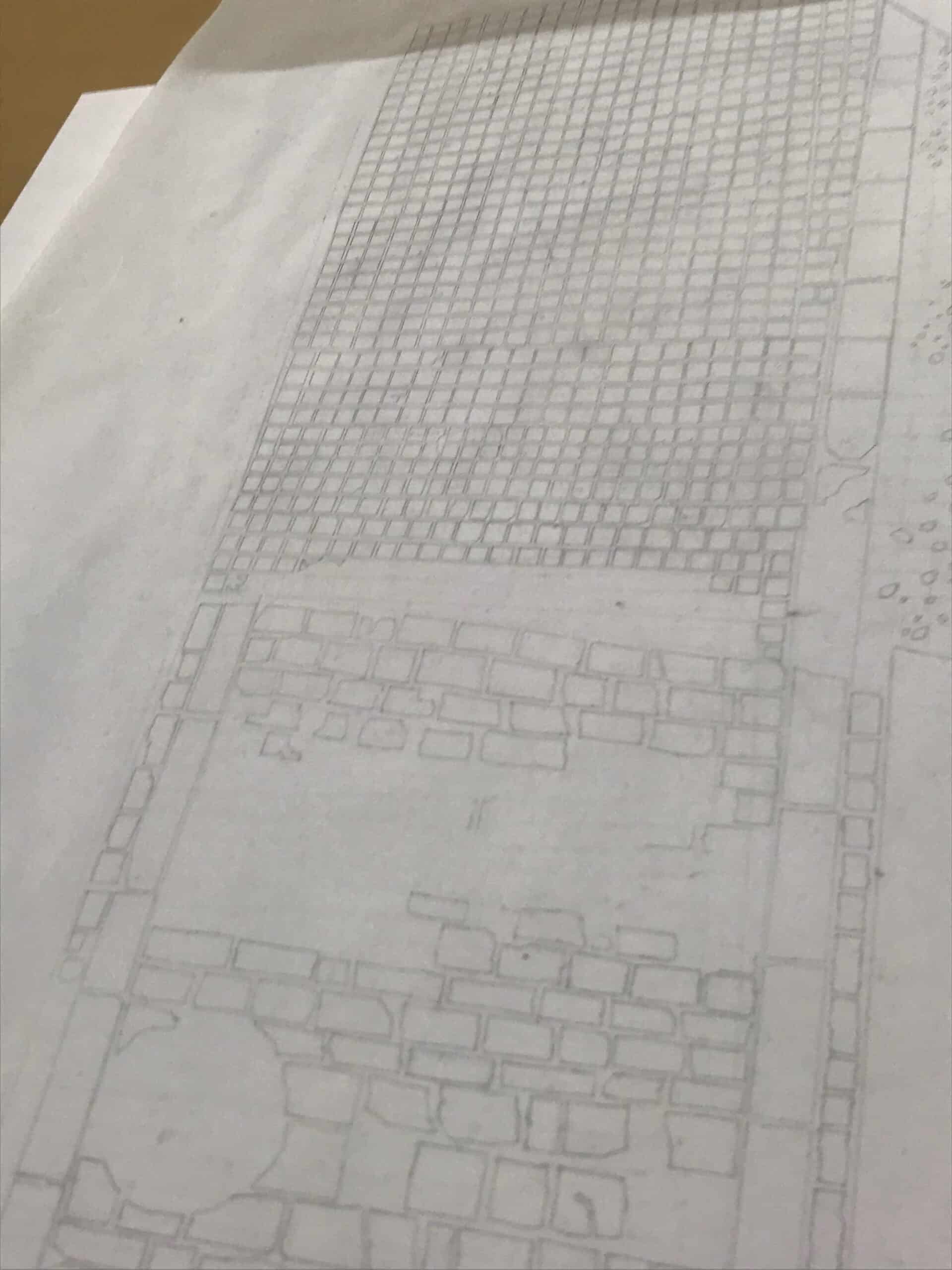

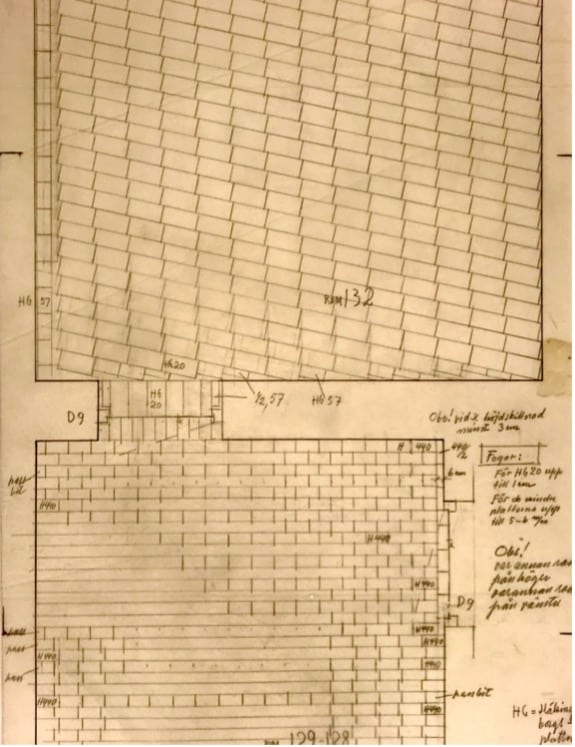

We are visiting the Drawing Archive at the Royal Castle and the Architecture Museum Archive – the pandemic has not yet been declared… In front of the original drawings, the obvious stares back at us: the ability of deep and concentrated focus must have been a prerequisite for making those drawings, but also for the initiated observation in real life of how light and darkness act on matter. And we found one numbered 1:1 hand drawing of each different model of brick.

Autumn 2020: KTH

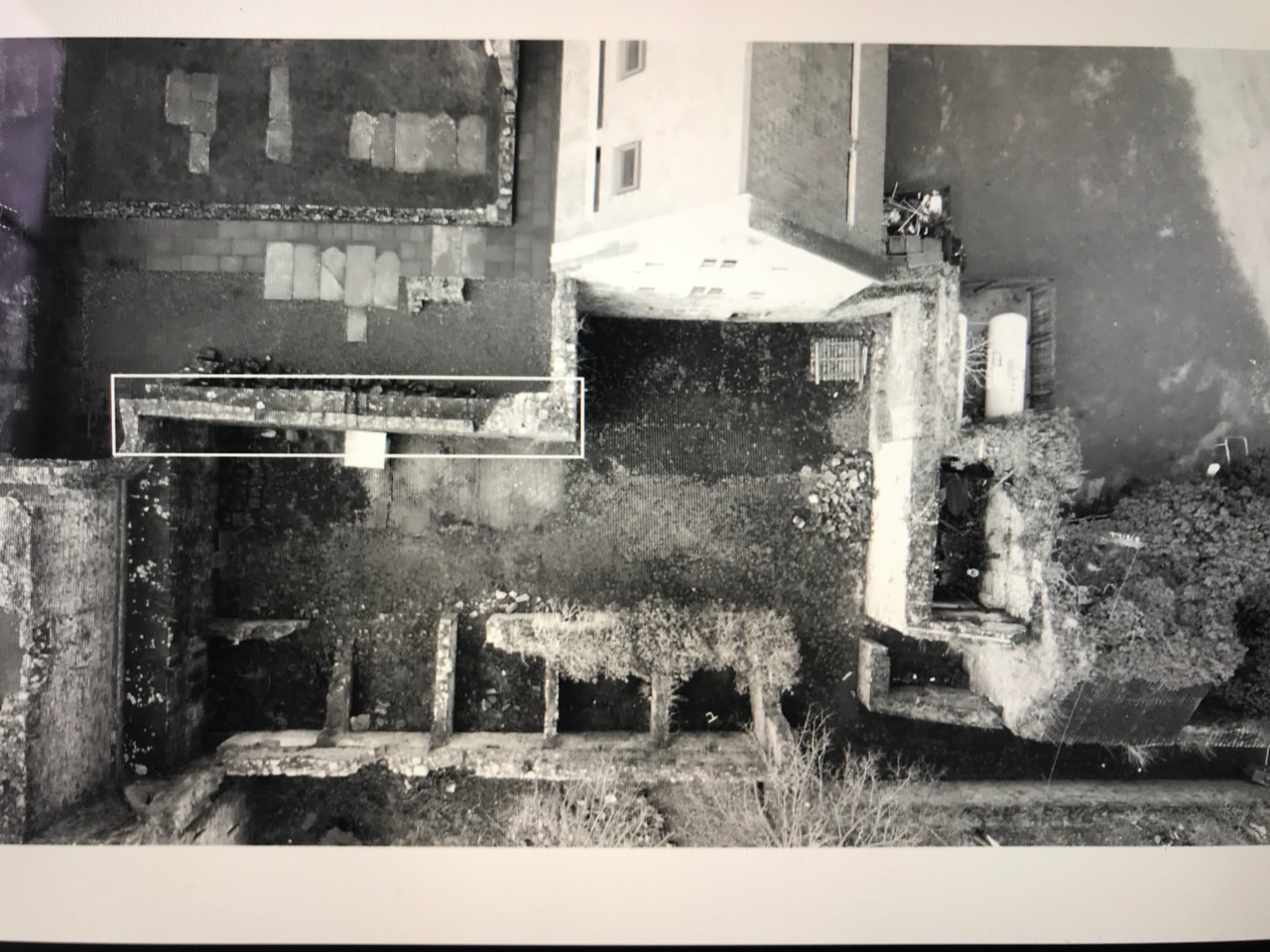

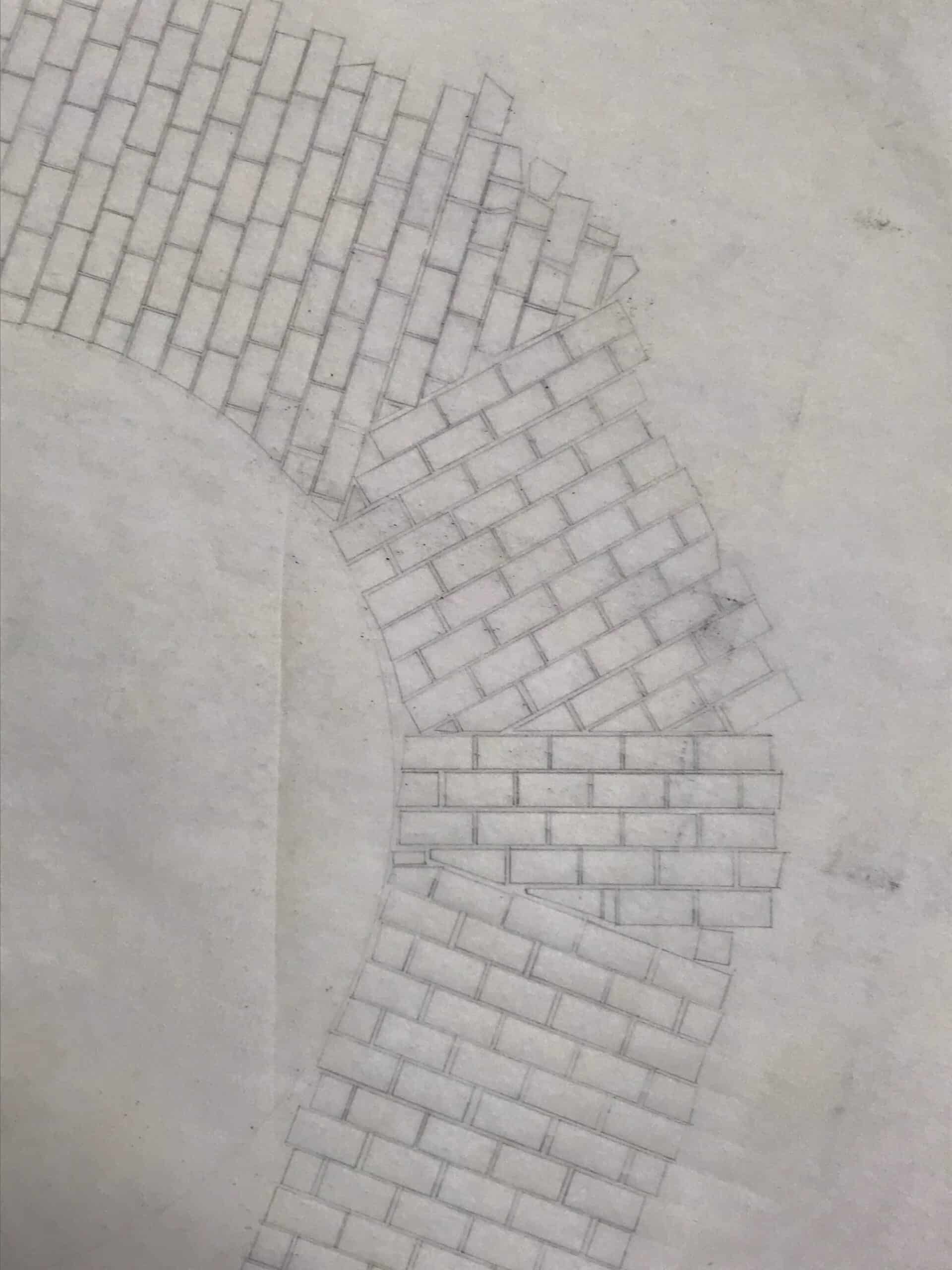

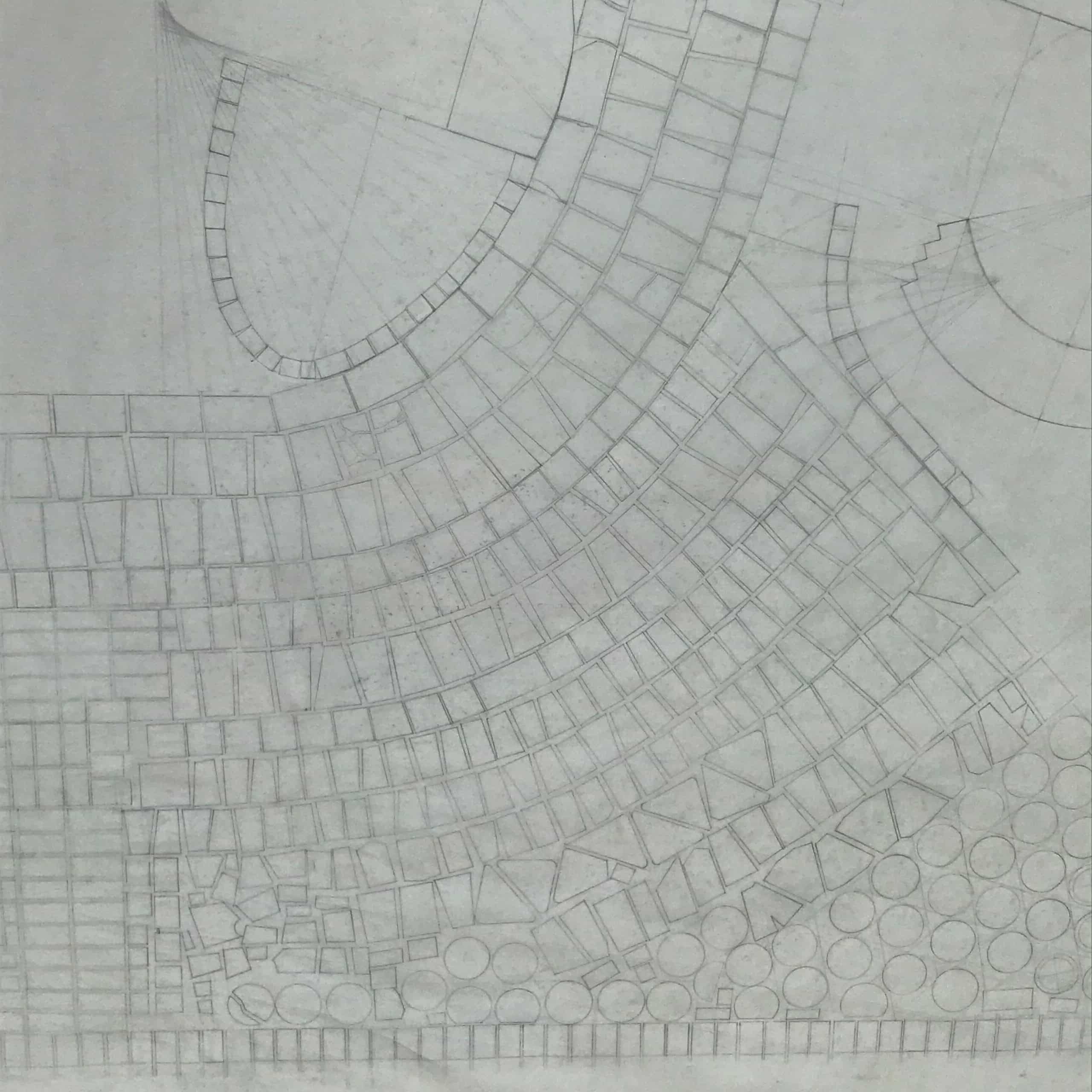

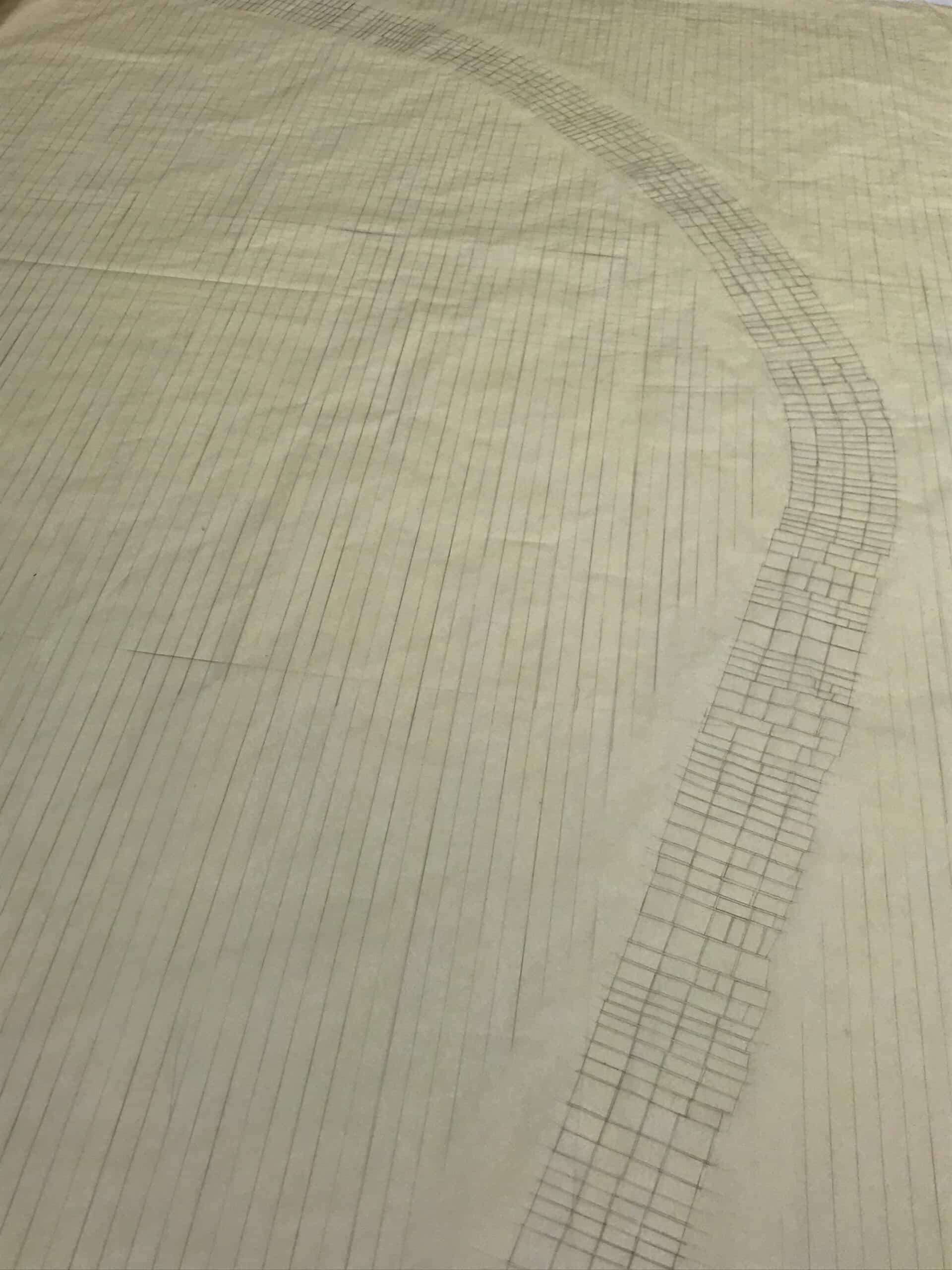

Embarking with 50 students in an elective course to survey and draw – by hand – the floors of St Mark by Lewerentz. It was Kieran Long, director of ArkDes museum of architecture ,who asked if I wanted to do it, with view to their great exhibition coming up later this year. Did I want to do it?! It was brilliant – the most appropriate theme for what was to be my last course at KTH after 39 years. Back home.

For many parts, particularly outdoors, there are no drawings of these floors in frost-proof ceramic tiles from Höganäs, of all sizes and shapes including leftovers and badly baked. Lewerentz may have made some sketches, now lost, but most of the work must have been directed by him on site in conversation with the craftsmen, and very much left to their skill, in a loose and trustful communication. 50 students is a lot during Covid restrictions. I could still at that time divide them into groups of 10–15, which worked fine. Measuring was with strings, plumb lines, stiff Swedish measuring rods – and photos. Drones were also used. American light-yellow tracing paper from my storage and clutch pencils 6H, 8H, 10H were used.

Spring 2021: still full Covid lock-down, no chance at all to see my Irish students this term either.

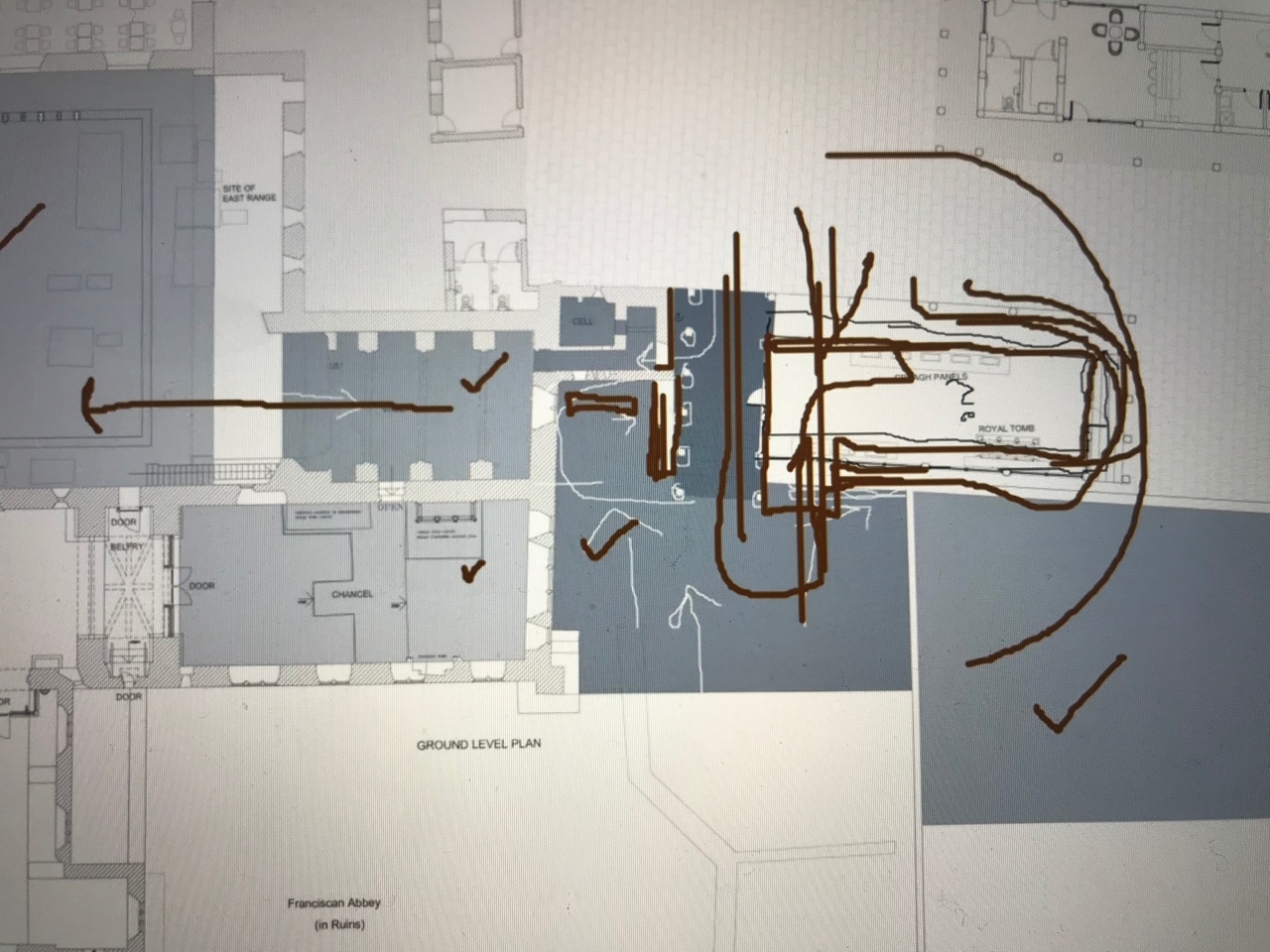

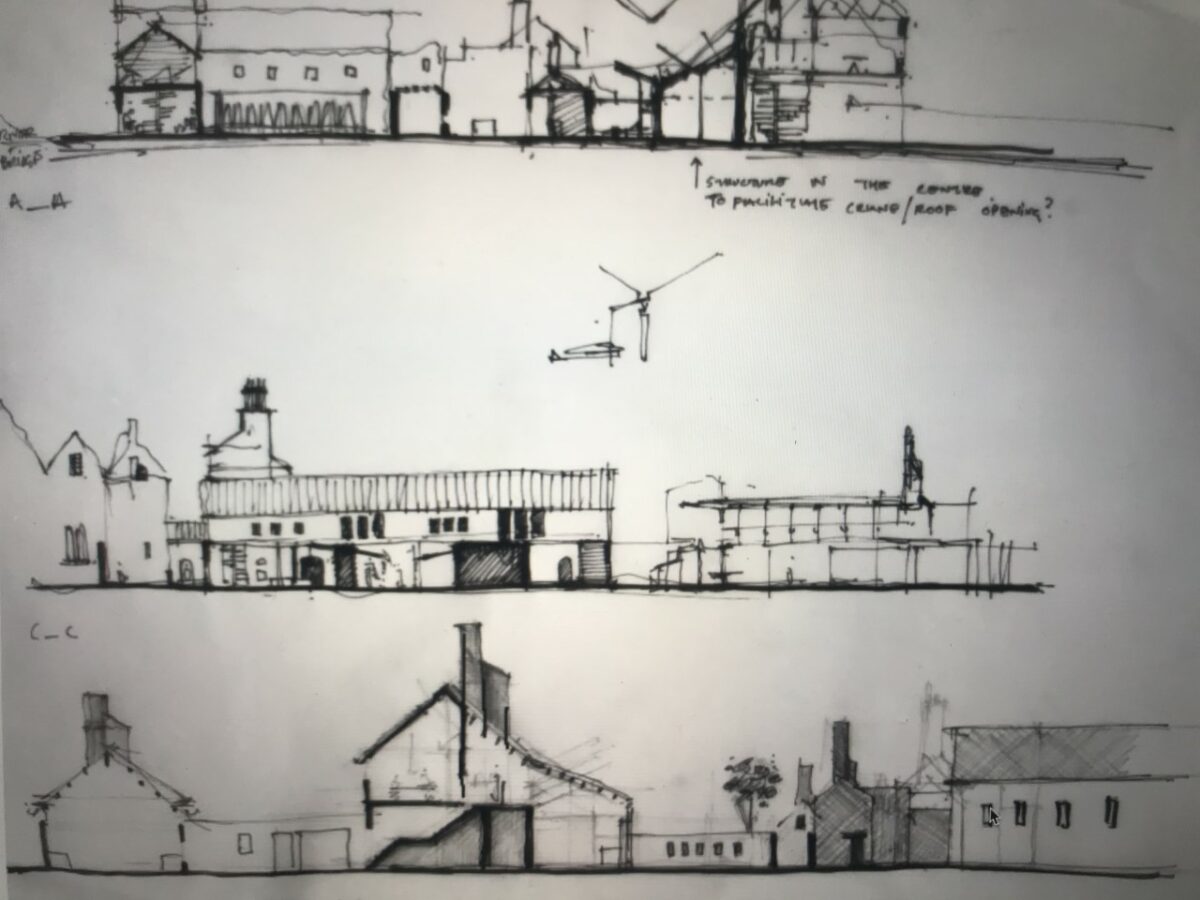

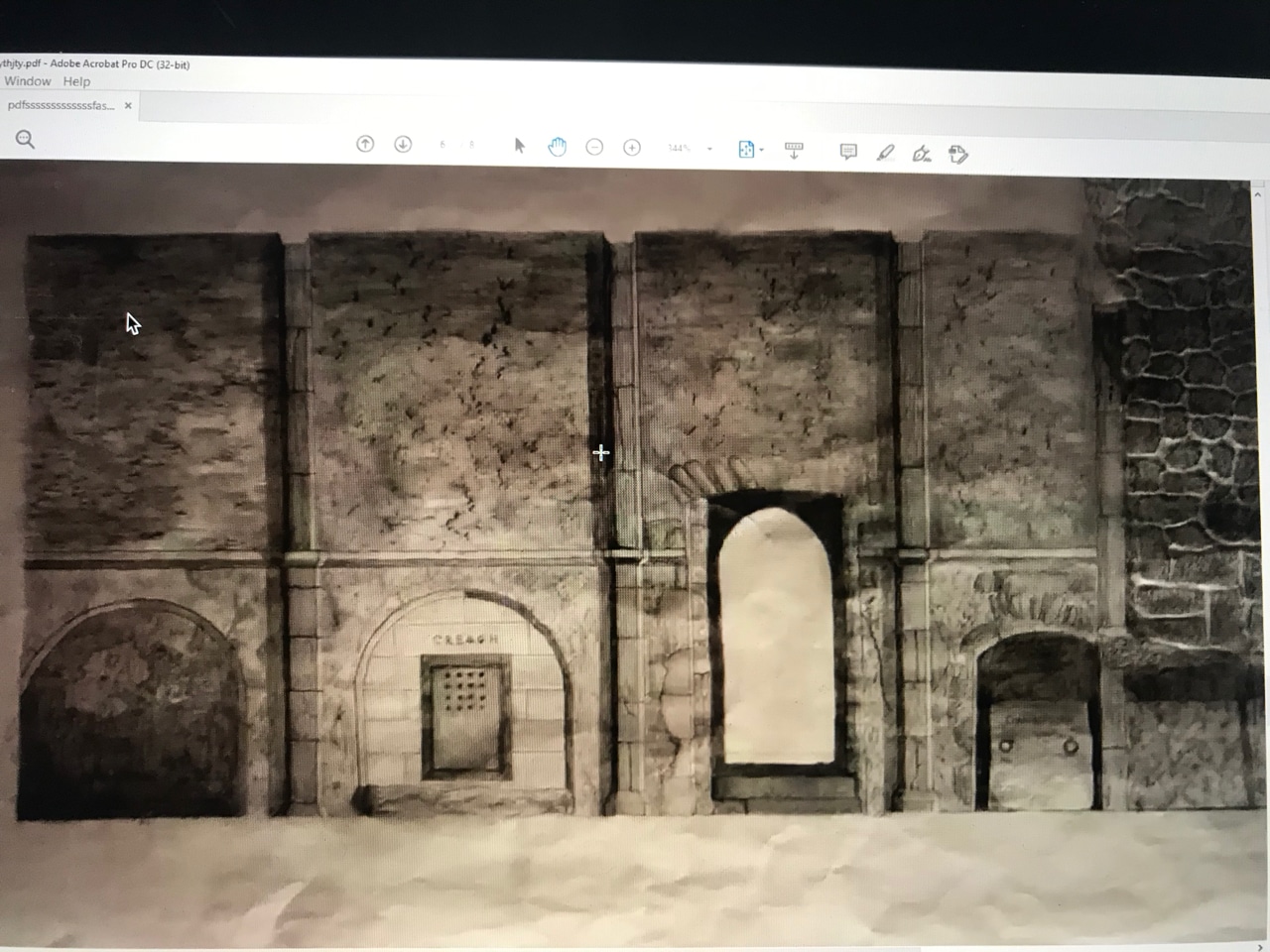

What more is appropriate in these circumstances than basing the year on a monastery in ruins, a friary – the embodiment of seclusion and isolation, turned into itself, even if friars were the most sociable of monks.

frustration at the screen?

not to sense the drawing – the real size of it, the tactile qualities

not to see the drawing properly – changing image before you have had a chance to sink into it

missing the coherence and the feeling of the whole – the relations between that and the parts

not able to let your eyes wonder as they like

you can draw on the screen, but you feel like drawing with a pin in butter: slippery and inexact

benefit of the screen?

students can lead you through, focus where they want and go really close

there is more focus on the work than on the person

you can draw on the drawing and maybe you dare to draw more – not sure all students are as enthusiastic each time…

benefit of the online meeting programmes?

you get great people to come and talk who might not have the time to travel normally

frustrations of the online meeting programmes?

you miss the pint of Guinness with them at Tom Collins or Locke’s Bar with Irish dancing…

and the walk through Limerick early morning ending with the best coffee in Ireland at Abbey River Café

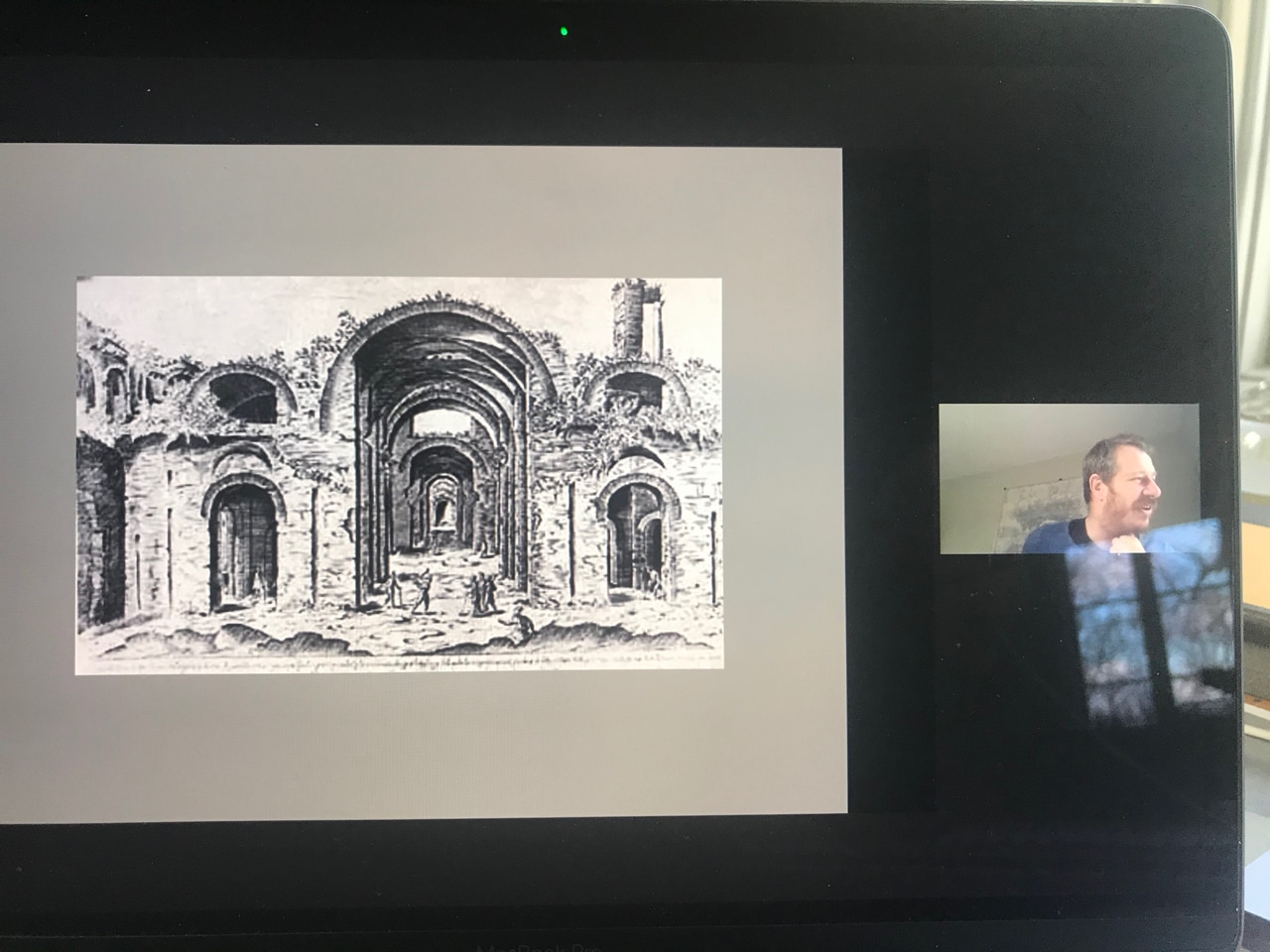

Below: all as seen on the screen… this is how it is now. Too many filters…not doing the work justice.