Pan Scroll Zoom 13: Tatiana Bilbao

– Tatiana Bilbao and Fabrizio Gallanti

This is the thirteenth in a series of texts edited by Fabrizio Gallanti on the challenges in the new world of online architectural teaching and, particularly, on the changing role of drawings in presentations and reviews. In this episode, Fabrizio interviews Tatiana Bilbao about her teaching at Yale School of Architecture and her practice Tatiana Bilbao Estudio.

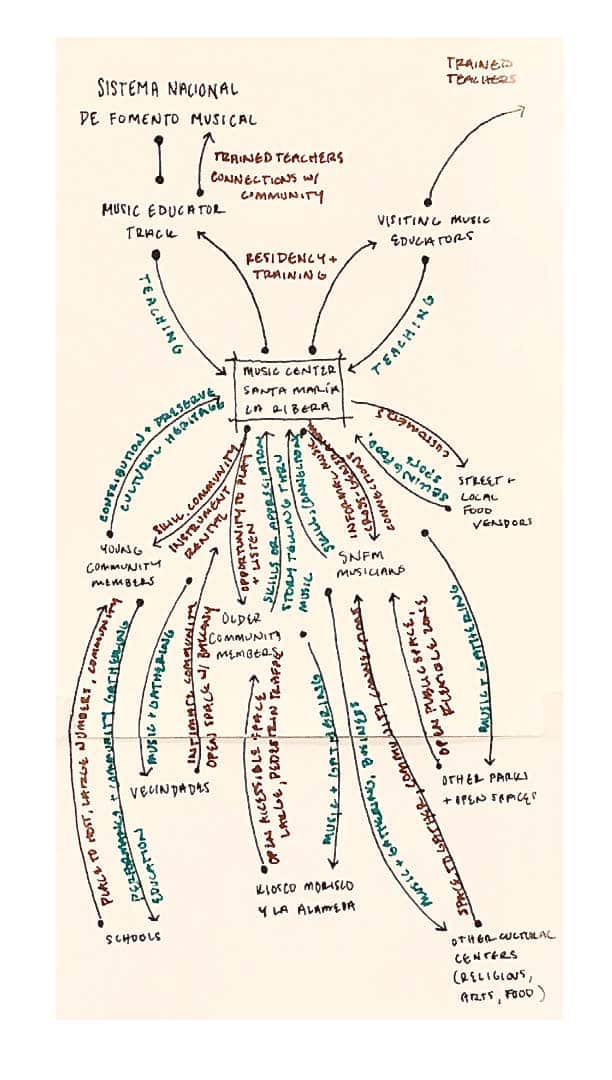

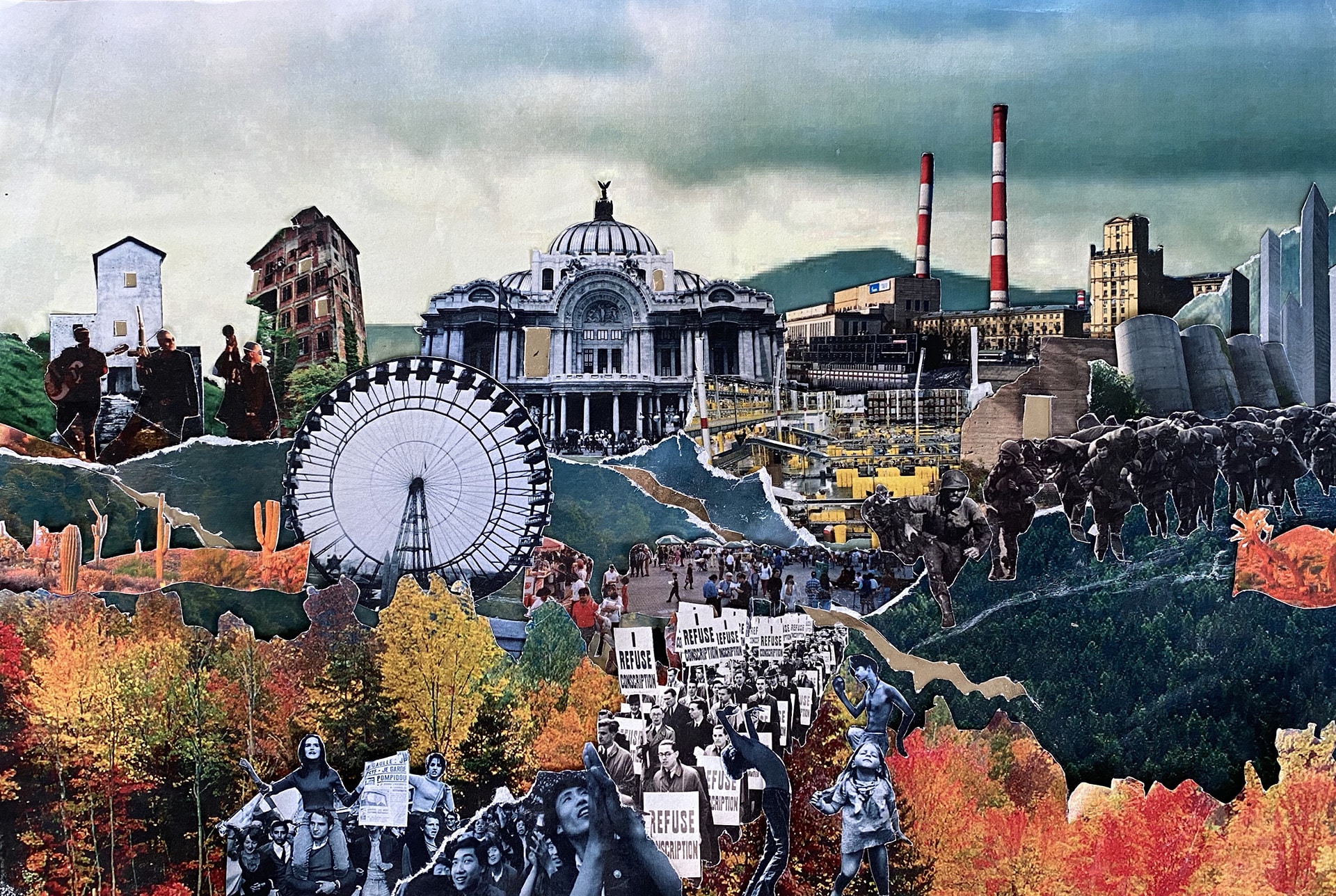

Fabrizio Gallanti: In the design studio that you taught at Yale in the spring of 2020, you mentioned that you wanted your students to be confronted with ‘reality’ on two different levels: first by inscribing their projects within a specific neighbourhood in Mexico City, which they had the luck to visit before the confinement, and second by asking them to collaborate on a single, large model that was both a reading of the place and a terrain of design possibilities. What were the reasons for this approach?

Tatiana Bilbao: The studio, ‘From Domesticity to Commons: Proposals for Contemporary Living’, had the purpose of understanding the ‘commons’ as a tool to open possibilities for neighbourhoods in dense cities, and to propose new ideas about living. I asked the students to work in Santa Maria la Ribera, a neighbourhood embedded in the centre of Mexico City, and a context that I know pretty well. I asked them to engage with the neighbourhood by trying to find the stories of the people living there. I believe that the way architects have been taught to analyse a site has erased the possibility of understanding the real sense and nature of places. While it is never possible to honestly understand a place, only relying on maps, statistics, or sun-tracking makes it even less possible. To start to get a sense of a site you need to get involved with the people that inhabit it and with its social, historical, economic, political, and natural context. This, of course, is very hard for anyone, even more so if you only have a month in which to do it.

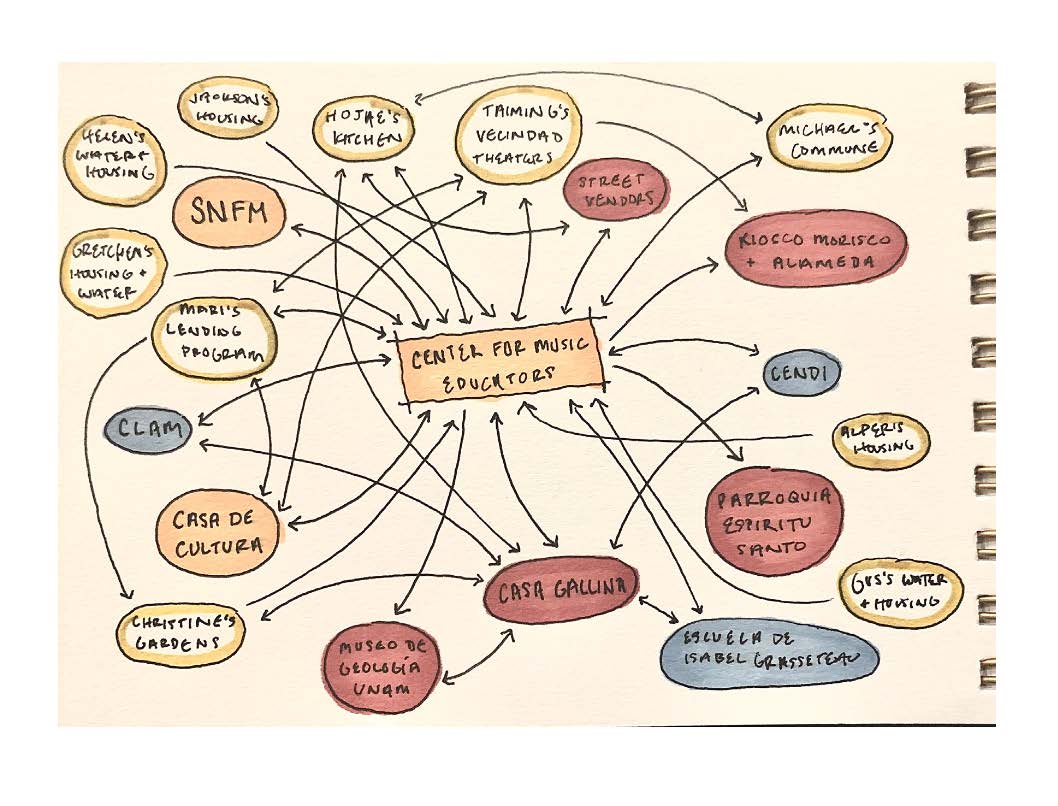

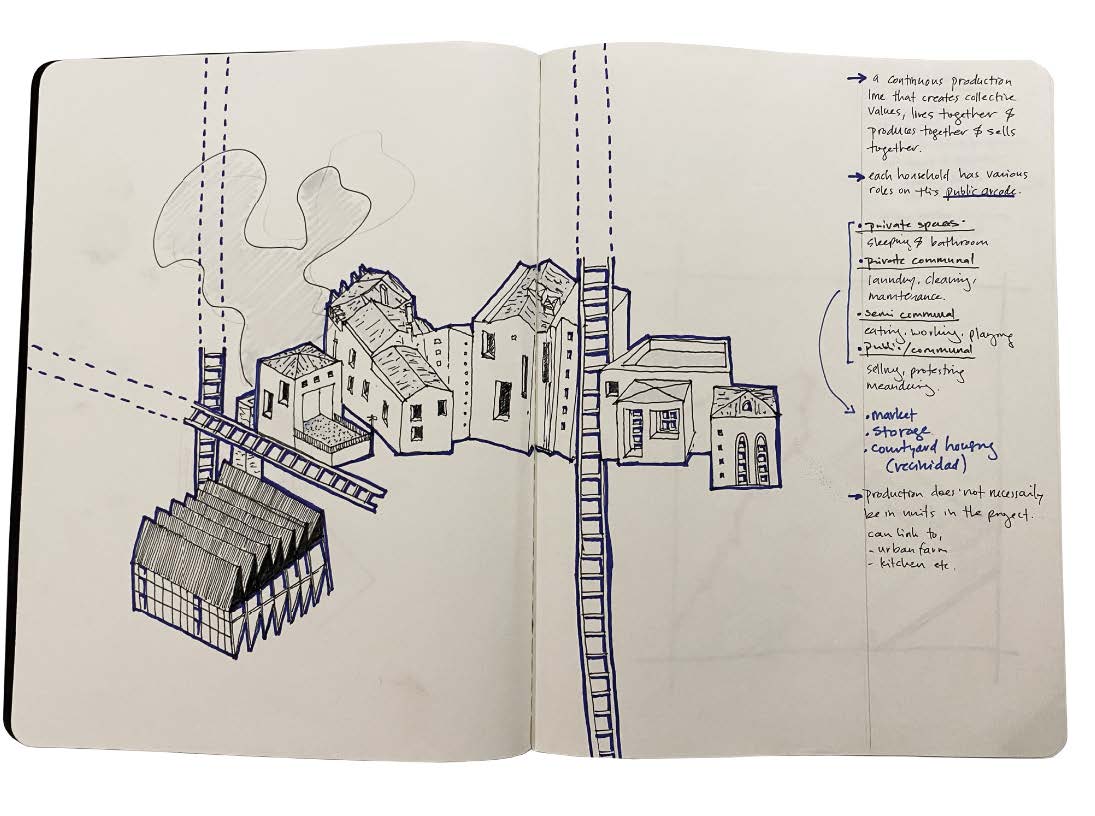

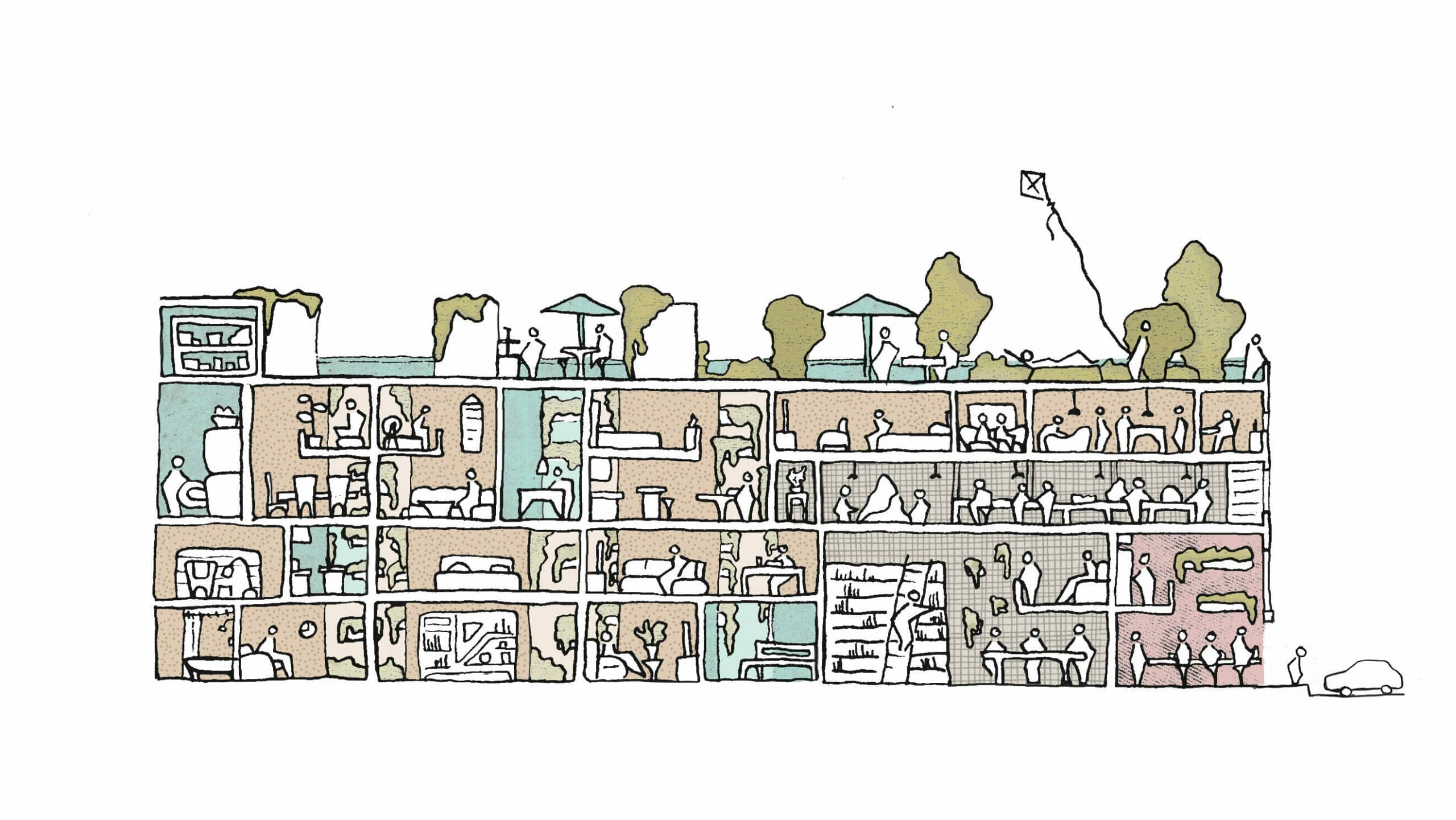

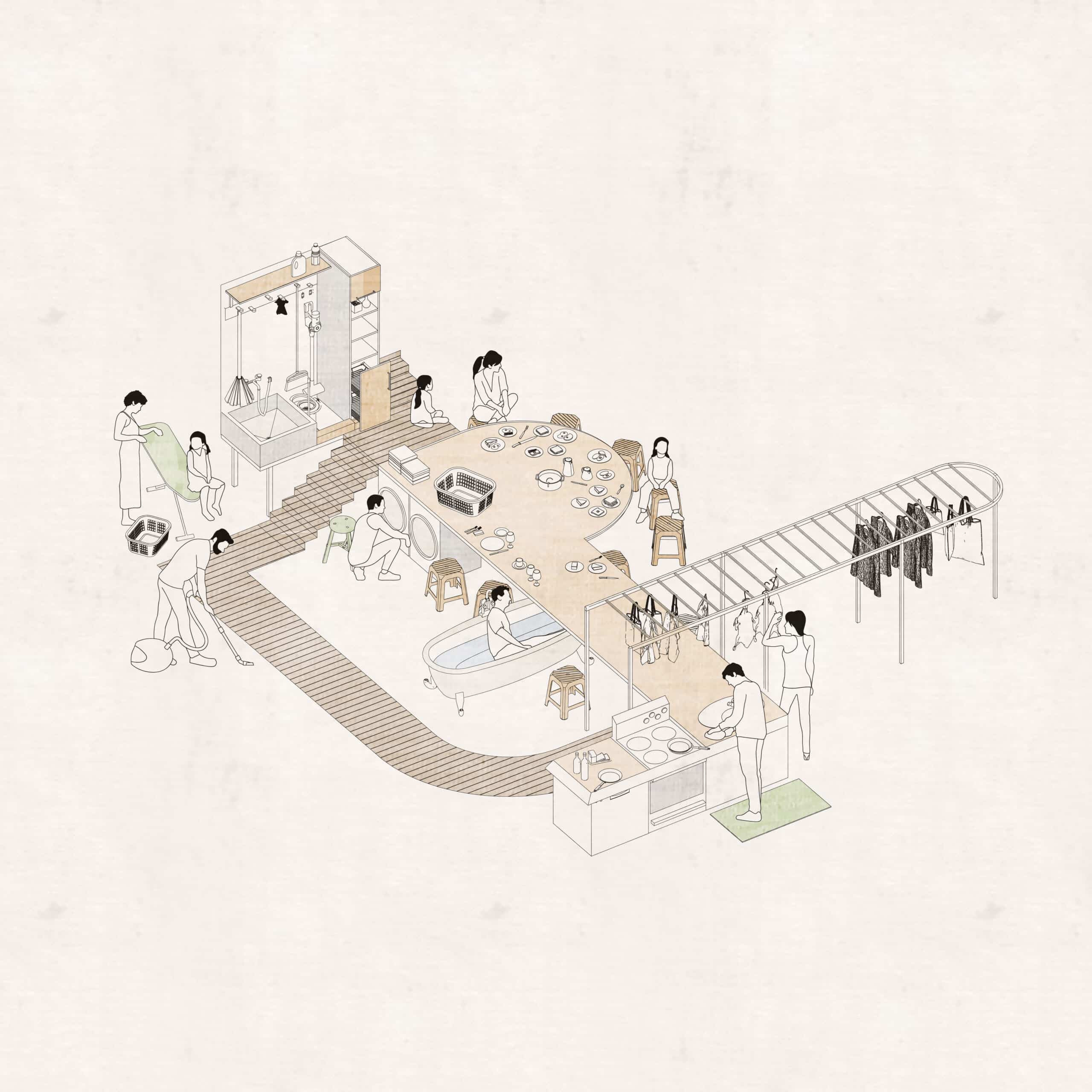

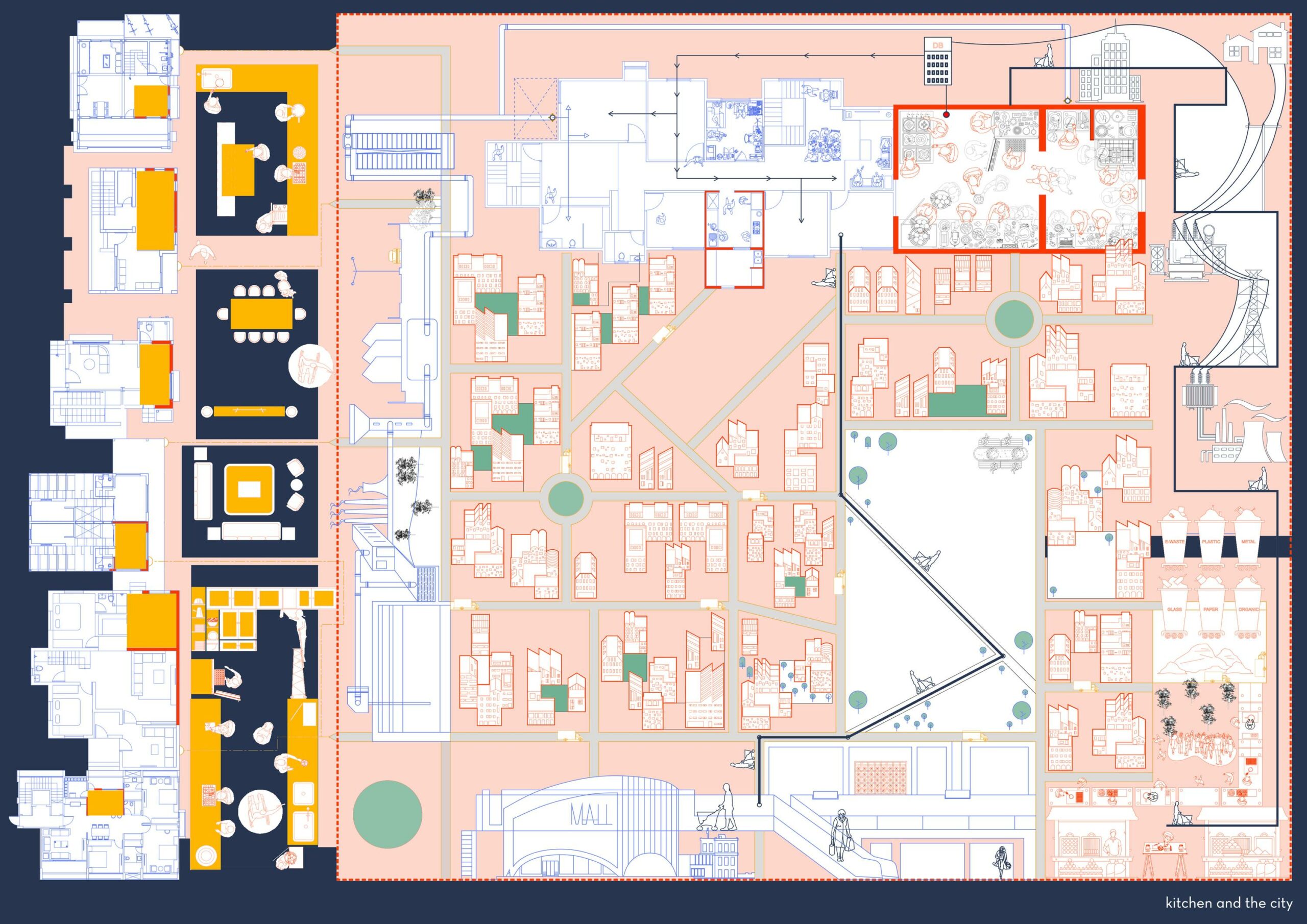

I asked the students to try to understand a very interesting type of neighbourhood: la vecindad, a specific typology of small collective-living entity that became popular in many Latin American cities in the nineteenth century. The specific form in Mexico has a uniquely scaled central patio surrounded by living units. Normally they are very narrow and deep in regard to the street. They vary in sizes, but usually they are between 10 and 25 units that surround a long patio (sometimes more like a corridor). These patios used to be an incredibly social areas: a space for engaging in common activities among the neighbours. In Santa Maria la Ribera, this type is found quite often. Unfortunately, the communal activities have been reduced to conflicts about who uses the central space and who stores things there. I wanted the students to understand what la vecindad of the twenty-first century could be. Can the common spaces become related to the neighbourhood at large? How can neighbours form new social relationships that are conducive to more collective and economically sustainable lifestyles?

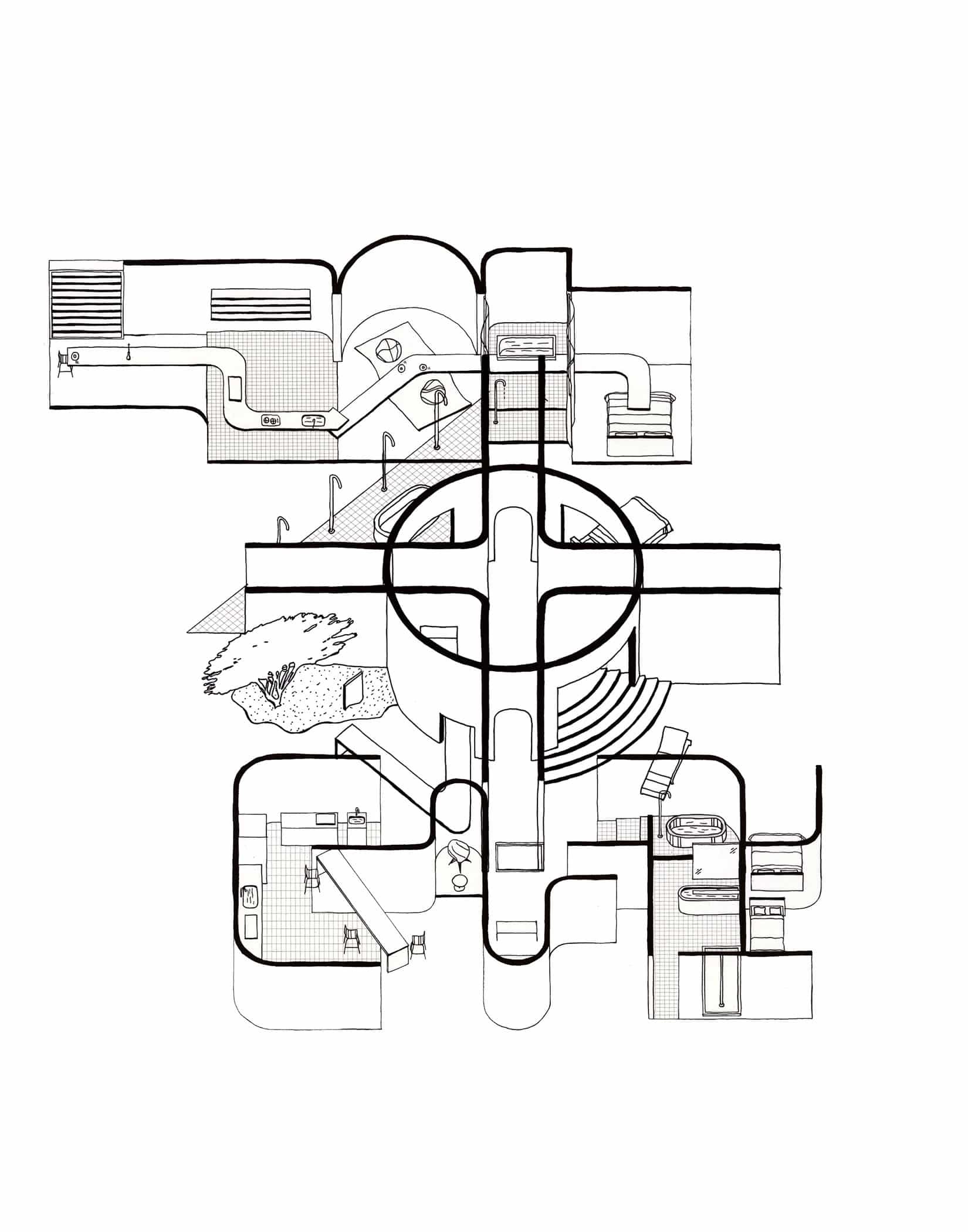

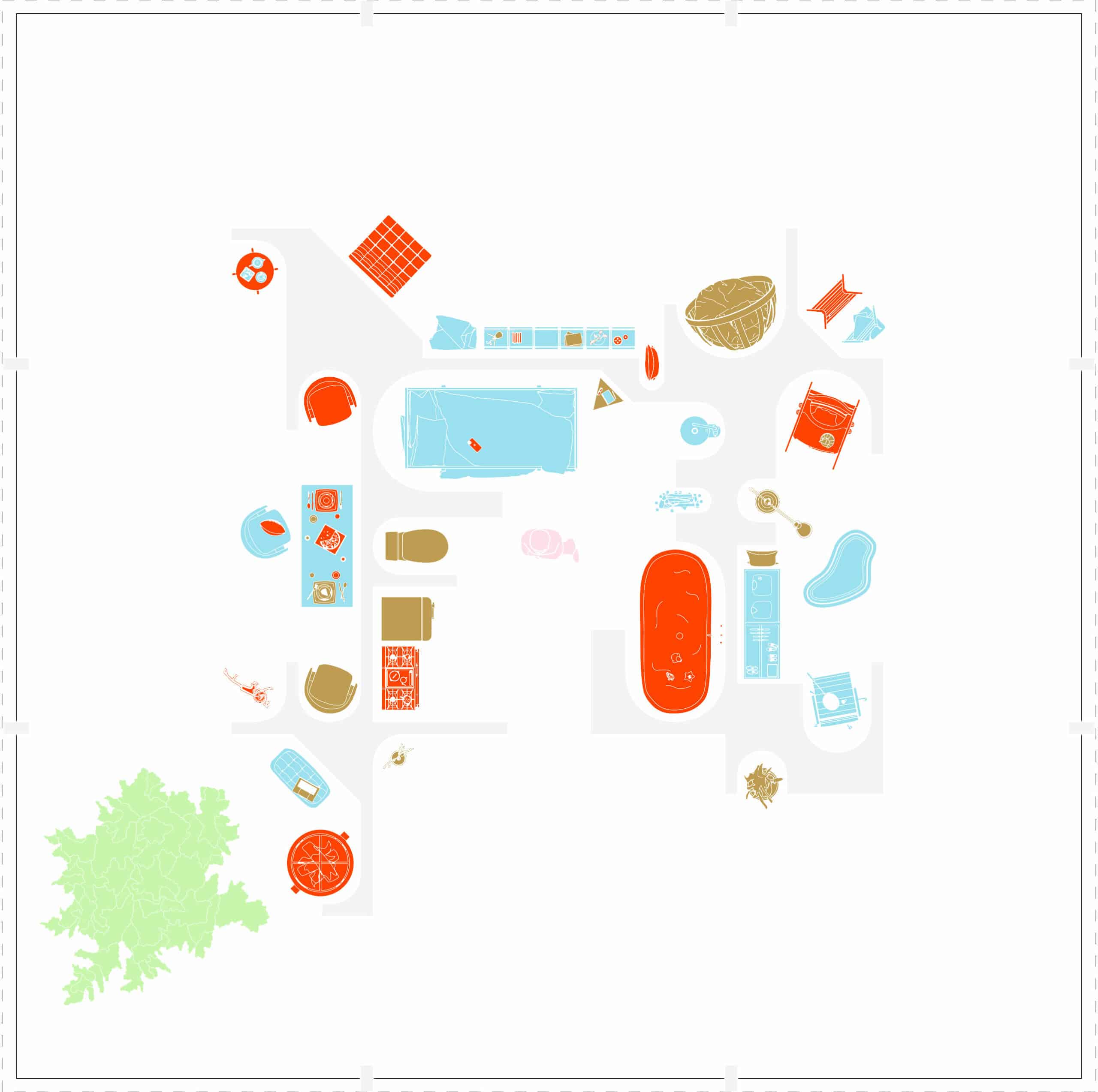

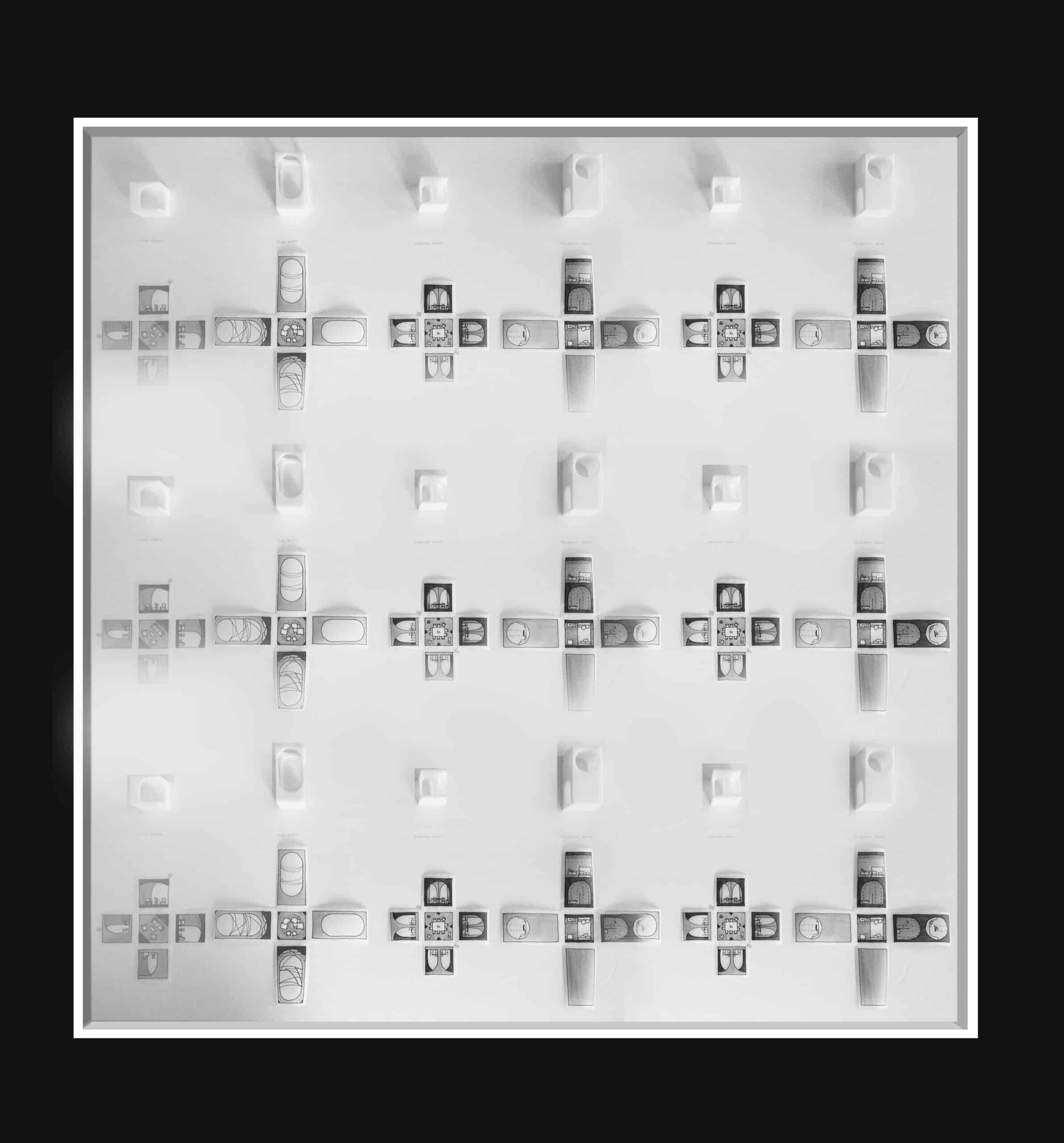

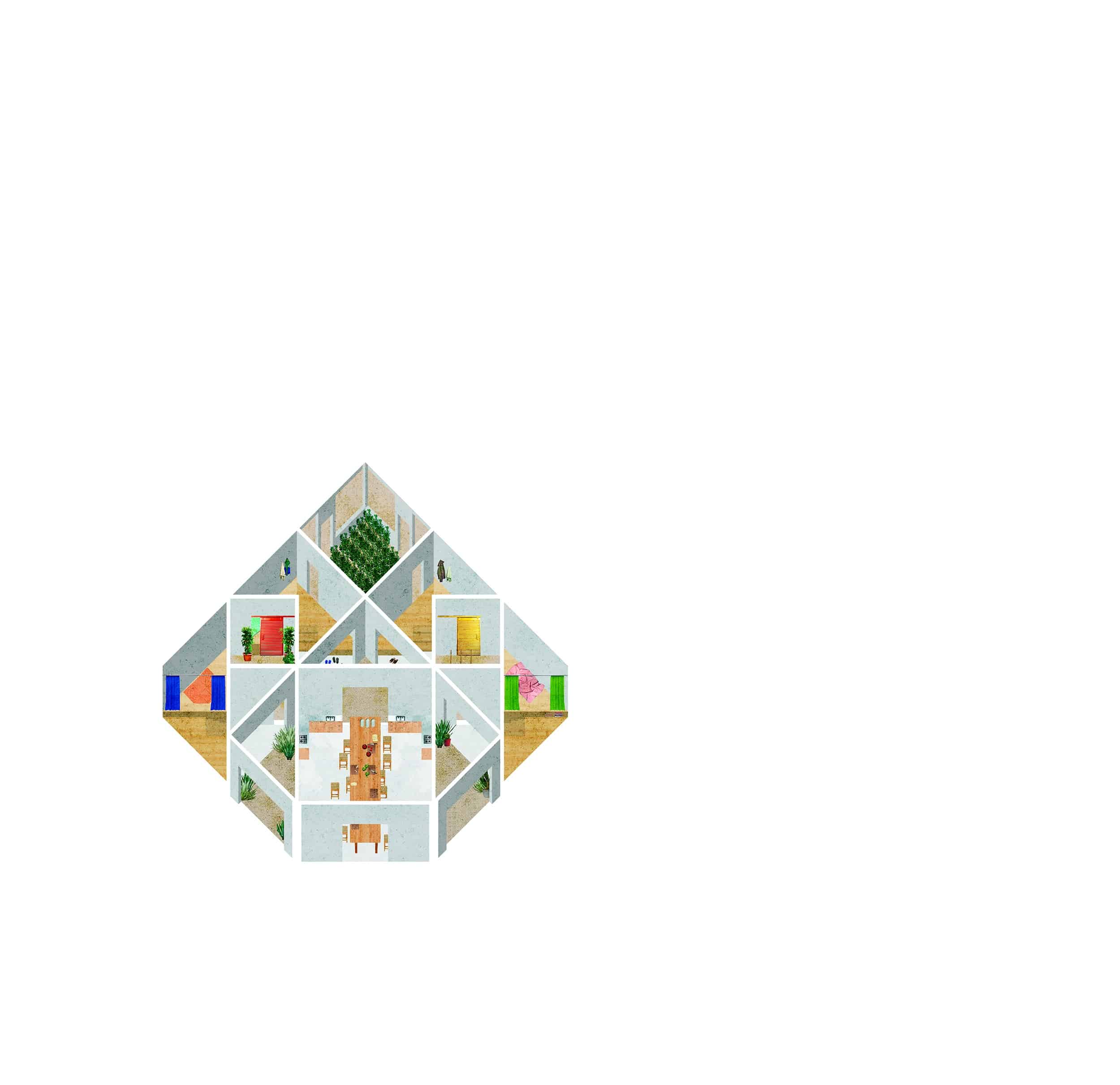

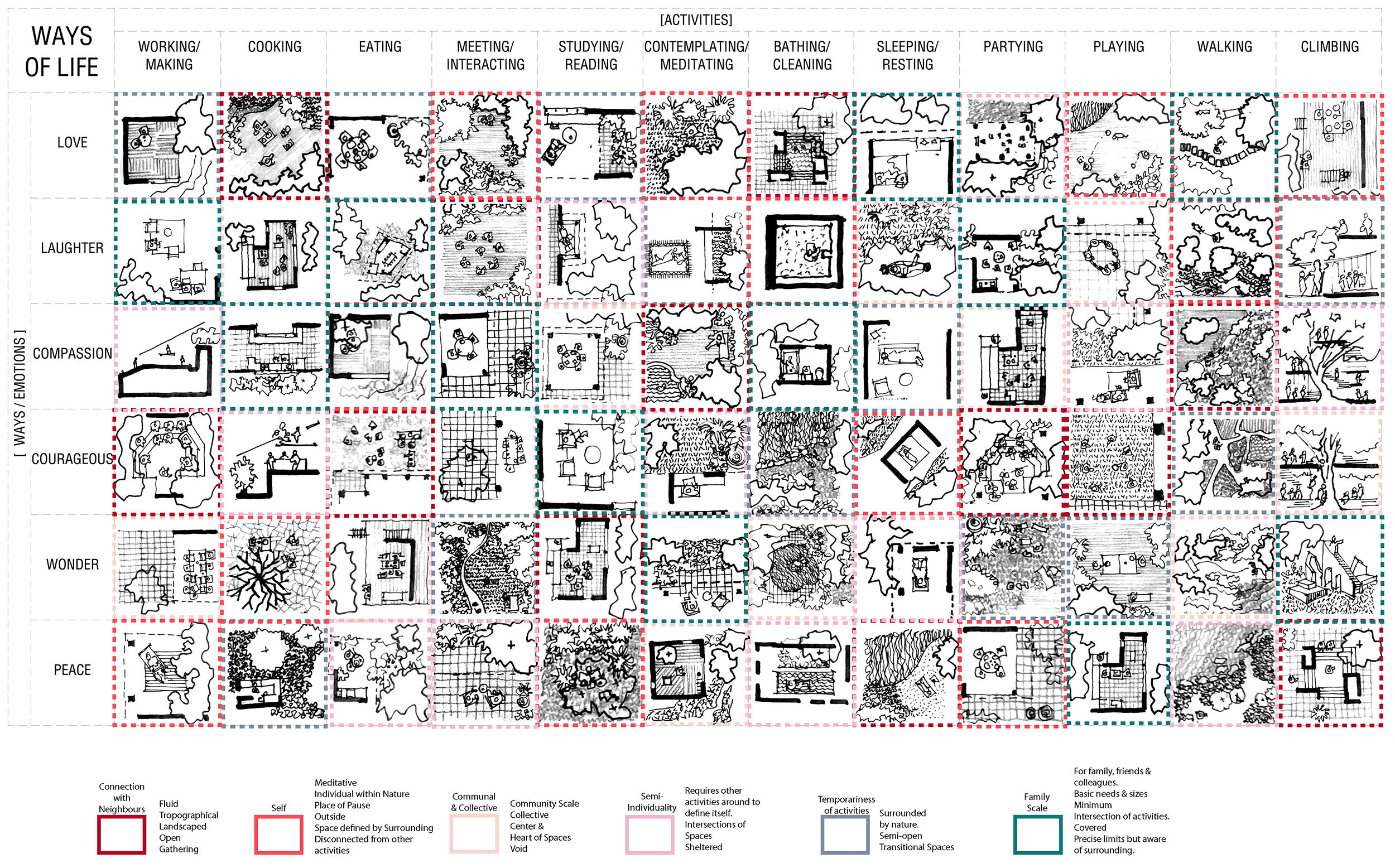

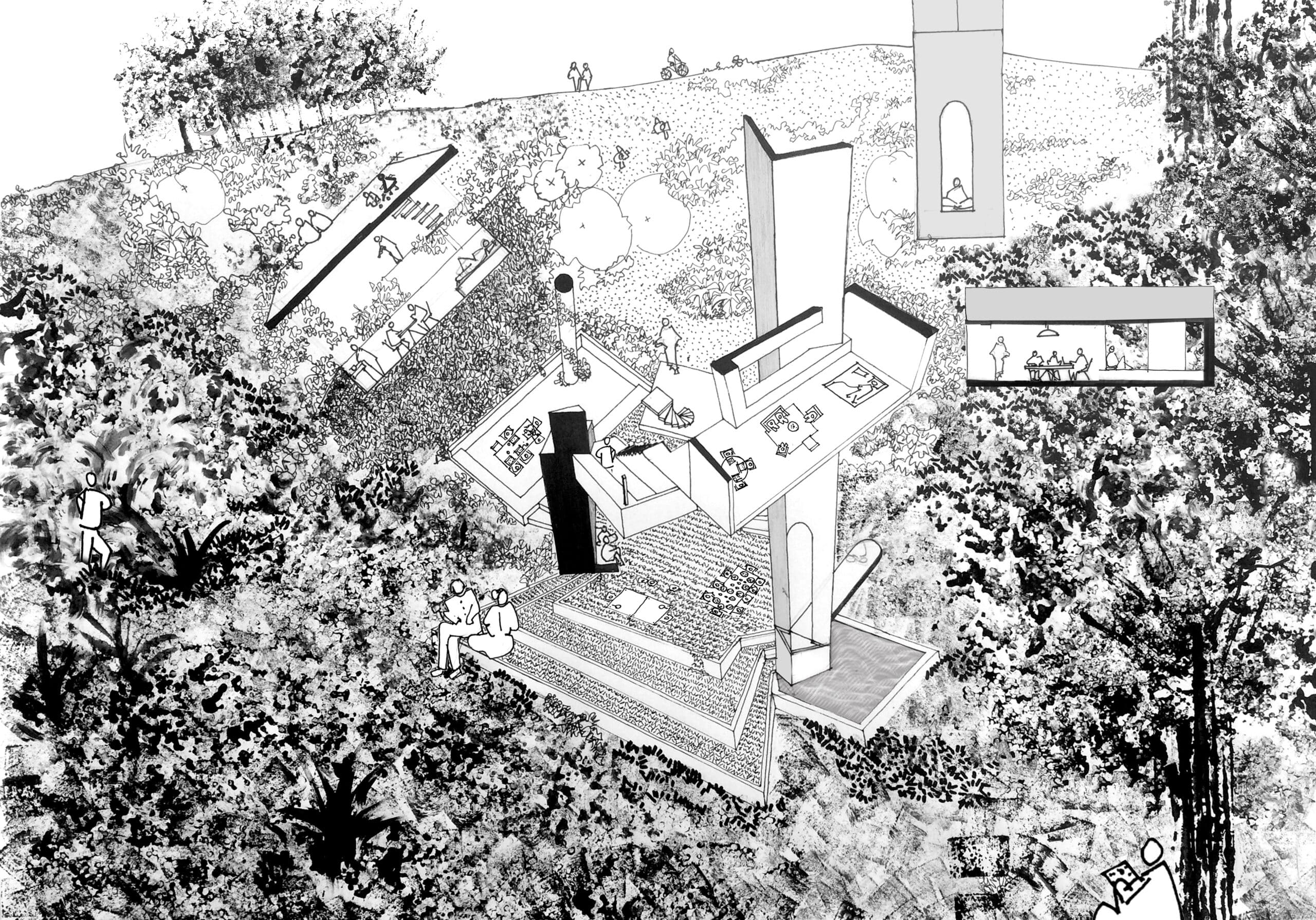

The students were challenged to understand as a group what those possible shared activities were and where they could take place. They were asked to create a very large physical model that would capture much more than just the scale and proportions of the place. The model was intended to be our most important tool and would be developed during the semester. As you can see in the images, the model was still to be filled in when the pandemic began. It started to capture their interpretations of the place but was still under development.

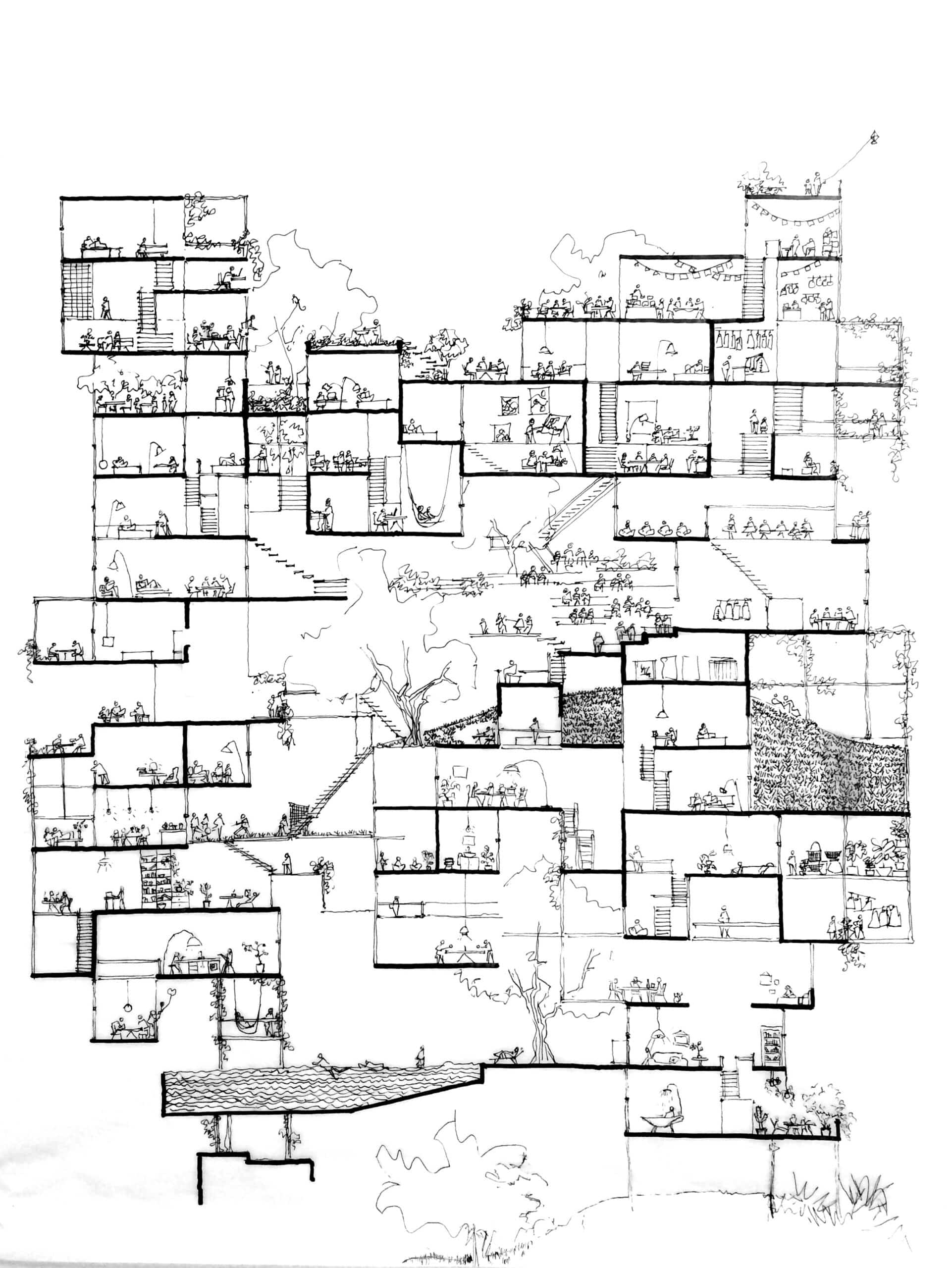

In addition to engaging with the neighbourhood, the students were asked to engage with their fellow students and to produce individual projects that would serve neighbourhood, showing alternative scenarios for citizens to engage differently with the place. The underlying idea was that novel activities could emerge and create a system of support for the inhabitants, occupying and activating common spaces.

FG: I find your position about how to get involved in a specific condition very pertinent. You completely move the focus from an idea of ‘objective’, scientific analysis, based on data and quantities (very much modernist), to a position in which the reading of a site becomes subjective and the project that emerges does not pretend to be the only possible solution. Within such an approach, how do you conceive representation – drawings or models? Are they seen as ways with which to engage in a conversation where one’s personal interpretation can be questioned and discussed? Does it become necessary to use representation to make individual interpretations legible and transmissible? And also, considering the current cultural moment, when students explore a neighbourhood what are the facts and what are the opinions? Can a drawing contain both?

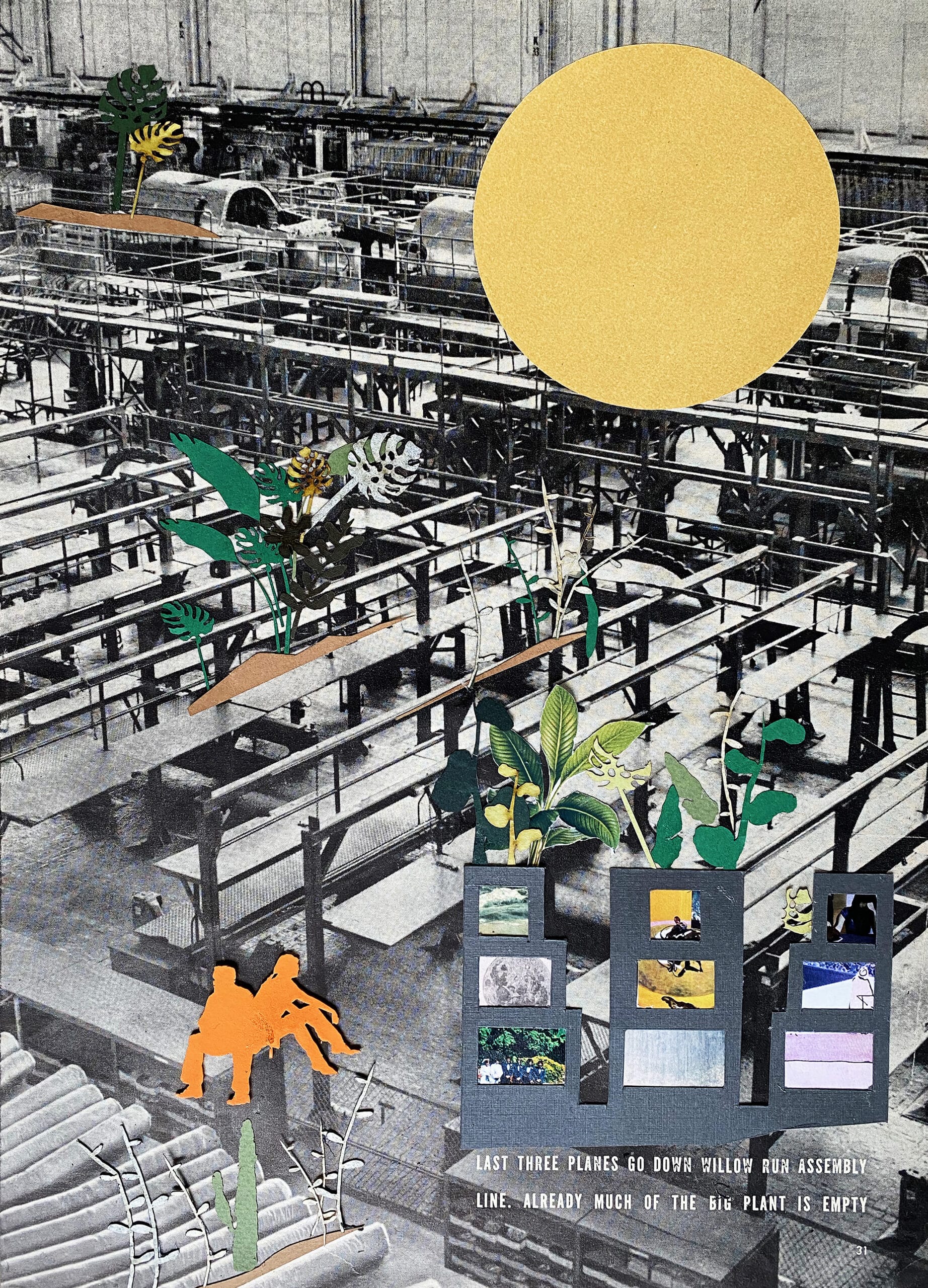

TB: In the same way that I believe that no one can possibly understand a place in reality (or not even a bit, I could say), I think that facts or statistics only allow you to ‘classify’ a place and not really to relate to it. The same happens with a drawing, or any type of representation. If we translate what we see or what we observe into conventional architectural representations, or the standard way of mapping, we lose the opportunity to really communicate with others. We tend to believe that a number, a fact, an ‘architectural’ drawing, will put you in the same position as another, but actually they hinder your ability to communicate, hiding your own position behind an idea of ‘objectivity’ and preventing others expressing their positions. There are instances where it might be necessary to reduce communication to facts or to conventional ways of drawing, but to understand a place, to conceive a project, or to relate to it, one needs to search for ways of communicating that are capable of opening a true dialogue. At this stage, personal interpretation is allowed, not questioned, and then it becomes inclusive.

I use facts and data early in the process as they allow me to build up a first understanding because I was trained to ‘read’ things like that, but I believe that when it comes to really trying to immerse yourself in a place you need much more than just ‘objectivities’. A drawing that is the physical representation of that understanding will necessarily use facts as a point of departure (dimensions and shapes for instance), but it needs the openness and freedom of one’s own personal interpretation to make it become subjective and therefore able to accept the another’s position as well. I believe that architecture needs to do the same: to become a platform for each of us to develop our own possibility of existence.

FG: Let’s return for a moment to the model at Yale University. Could you explain how it was made and what you learnt, but also what happened after confinement was imposed? I assume that you had to improvise some radical changes to the studio.

TB: The main part of the studio work was intended to be done physically on that large model. The idea of the commons was not only for the projects in the neighbourhood, we also wanted the students to work together. Each person had to develop a project that would be inserted in this neighbourhood with the intention of creating a space that would become a platform for social exchange. The project would be theirs, but it would also have to take into account the intervention at large, constantly negotiating with the other students, in terms of functions and forms. We wanted the students to engage as much as possible with the neighbourhood, but also amongst themselves. We wanted projects that could be inserted in the sector and that could act not only within a specific space but could also fit into a wider system of spaces and reinforce the social fabric.

We asked the group to develop a large-scale model of the 4 x 3 blocks that they were focusing on. The model was not just the representation of the physical configuration of the place, but of its historical transformation and the absolutely critical natural situation (the neighbourhood has sunk more than 14 metres), and the socio-cultural aspects of the neighbourhood today. At midterm, the model was half-developed, it had captured the first interpretations of the place and had allowed us already to start to discuss the many interesting aspects of the place that were starting to substantially inform the designs. The model was done by the entire group and the task of allowing all these people to make it and to be able to express their own opinions and projects became a huge challenge. Commons are places of negotiation and of conflict and that is exactly what helps build the possibility of a collective space. The physical presence of our bodies around the model was already giving us the possibility to develop a project completely in other terms.

With no doubt, however, the biggest difficulty happened right after midterm when we had to leave this model behind, losing the physical interaction with the model and amongst us. I believe that the studio was able to continue and at the end to produce amazing results because of the initial half-semester together. But, to tell you the truth, none of us were able to understand the situation and to react and to change things as radically as they should have been changed. We just moved online and tried to continue to work as before and just continue the project. But, thinking about it now, that studio needed a total shift, as the conditions shifted completely. I was not that clever.

FG: The idea of the commons is very important in your practice. I can think in particular in your research around affordable housing. What strikes me is how you always look for non-conventional solutions that can respond to changes in the structure of the family: the incorporation of functions such as commerce or labour within the domestic space. For you, the house is never a fixed entity but rather a dynamic field that is responsive to societal changes. I would like to understand how drawings and models are then mobilised in order to generate multiple dialogues, not just with your clients, who are often public agencies, but with the final users. I feel the same attitude that you use within the university: representation as a tool for exchange.

TB: I believe that the house needs to be a personal dynamic entity, and more than being responsive to societal changes, it needs to be able to let anyone compose their own idea of domesticity. The house has been the determinant to define societal behaviours and has been used as the ultimate tool to perpetuate capitalism. Drawings and models are modes of representation that, with their capacity to shape thought, are able also to shape behaviours. So, in the same way that they have been used to pursue a specific agenda, they can be hacked to pursue others. Everyone has the right to be represented in space, and this can start by being represented in drawings and models. It is definitely a way to open alternative channels for architectural representation. This also opens new forms of collectivity that I find even more interesting, collectivity by representation, and this is why I believe in the whole concept of the commons.

I teach in the USA to be able to immerse myself in an environment that allows me to understand the implications of the very symbiotic relationship that has been building between Mexico and the USA over the years. For me, it is a tool for the construction of identity, probably my own identity. In the end it is again a matter of representation.

FG: When you are engaged with communities, do you and your collaborators show up with architectural proposals on paper and models, present them, and afterwards integrate the feedback? How many meetings do you have? I am very interested to know how things are done as I imagine a lot of resemblance to the engagement of your Yale students with Santa Maria la Ribera.

TB: Every work session in our practice is different – or at least that is how I think of them. Each project has a completely new process, which is terrible for the people that do the planning and manage our finances… but this is how we operate. It is common to start with lots of questions that we want to raise with a project and its associated process. We begin with numerous brainstorming sessions and lots of talks that are accompanied by a very visual component. We put many things on the table: photos, objects, drawings, paintings, videos, texts, models, physical materials. One of the most memorable sessions that I can recall happened when designing a house in Monterrey. Vanesa, who was the client, arrived at the table with a kettle, a pan and a jar. She said those where her most important possessions and she wanted her house to reflect them! Another interesting one was when Viviana, who was building her weekend house in Ajijic, put the scenario of her daughter’s boyfriend being left-handed at the centre of the discussion – at the time her daughter was 13 and had no boyfriend! This is the type of thing that we encourage to happen.

At the school we try to enable a rich conversation that can question everything in the process. We rarely set a very defined timeline, so we end up having as many meetings as necessary. We believe that our architecture also welcomes the conversation to continue over the years, becoming more interesting after it is built and even more so as it is inhabited.

When I was still in school myself, and now that I teach, I usually enter any design process with a huge illusion of an unknown world. I am open to understand and to ‘discover’ things in the process. For the students, this is sometimes very scary, they are used to having professors that describe the whole structure of the course from the beginning to the end and they know exactly what they need to do and what to expect. This never happens in our studios, just as it never happens in our projects. Somehow, we have managed to stay inside budgets and to deliver things on time (absolutely thanks to my very organised and creative partners Catia and Juan Pablo). But we really do start without an established plan about the evolution of the ideas. The objective is to have the practical issues set and, as for the design studios in school, we know when we need to achieve things but we don’t know how the way will be paved. Something that needs to be clear, though, is that we are not trying to innovate or invent something original every time. We do research, we keep ourselves informed of the work of our peers, but we think that each project has its own place, its own way, its own dialogue around it. I believe that we allow for each identity and diversity to determine the process.

FG: I think that in general you are being too modest. If I look at the drawings of the projects in Santa Maria la Ribera developed at Yale I am intrigued by how diverse they are and yet how they always hit the right objective of being capable of communicating outside the conventions of the university space. You clearly do not teach a ‘style’ of drawings but clearly there is something that your students have absorbed from you. I was asking about how you operate in your profession as I think that there is one part of the answer, but I have the suspicion that I am missing something. How did you push them to achieve that level of precision and intimacy, especially after you had to abandon the studio and go online? Please give us the magic recipe!

TB: There might not be a magic recipe, but there are many ingredients. First, I ask the students to really observe people and to engage with them, to spend time together. Understanding attitudes, feelings, relationships, things people do (not as statistics and not from books and academic research) observation, either in the place itself or through other media, will all bring them closer to people. Indeed, they should be very objective and to also allow their own subjective interpretation to be informing the process.

The other important ingredient is intuition. I work much more with my intuition than by references. Obviously, my personal references built my mindset, and my intuition is shaped by my acquired knowledge, but I also encourage students to listen to other students and escape from restrictive systems of examples, top-down and academic. I try to find a collective method that is developed according to the people around the table, so this is why also every studio has its own path, its own process, as systems of exchange and negotiation in a collective always change depending on who forms that collective.

Lina Bo Bardi wrote: ‘Between the artful, eloquent man of letters, the art critic or the obscurantists metaphysical, the poet on the one hand and the scientist or the isolated technician on the other, there lies a mass of humanity that is facing the problems of existence with despondency, abandoned by culture. I could say that between the businessman, the obscurantist politician on one hand and the architects and the isolated academics on the other, there lies a mass of humanity that is facing the problems of existence with despondency, abandoned by the system’.

FG: How would you assess the role of drawing in different schools? I ask you this as I know that you have taught in quite different places. I have the impression that in US universities, drawings seem to be more abstract, speculative and conceptual because after graduation students will still have to spend a long time in offices before getting their professional licence. In other contexts, such as Spain, Switzerland, or Chile, they tend to incorporate notions of construction, details, technical equipment. Have you registered differences in your experiences and if so ow do you mobilise them in your teaching?

TB: This is a very interesting question and I have to say that I have not paid much attention specifically to the drawings; I have, in the past, put attention on the method and the outcome. What I can say is that in the USA it is hard to ask students to be open to speculate from the beginning. They are used to having a brief with lots of details on what the ‘problem’ is that they need to solve. For me, there is never a problem to solve, and it is never about solving problems. Who are we architects to solve anything? There are issues to address, and I never give a detailed brief. I don’t believe there should be ever one. I don’t have detailed expectations ever. In our studios, things take shape while observing, researching and constructing thinking, it’s very often that students feel ‘lost’ more than half the term. For me that tension is what we need so that students question things.

On the contrary, as you say, when there is a very detailed brief, they are able to create more speculative abstract responses. On the other hand, I find that in other contexts, such as the ones you describe, it seems ‘easier’ to have a more speculative brief, but they often try to find concrete solutions faster. I have experienced that myself. I had a very hands-on education, learning form-finding solutions for very urgent matters, such as understanding how to build houses with local materials in very small communities. When you have those projects in school it is hard to speculate on notions of the future, or the broader agency of architecture, or other things. I have learnt through the years how to mediate and juggle between those, but I think there are many more other possibilities.

FG: You mention the necessity to use drawings to engage different subjects in a dialogue and clearly this is expressed also in the work of your students. Have you recognised techniques that seem to be more effective than others? For instance, the large model made with the students at Yale. Are models better for having conversations?

TB: I believe that it is imperative that within architecture we start speaking from subject to subject. Models are often artefacts that are ‘easy to relate to’. I believe that the brain translates information in spatial ways, and so models are efficient. We are born in space, we live in a space and we are determined by it – whether we like it or not, whether we are conscious of it or not. I have noticed that models are efficient tools of communication, but they also come with their own biases. Models are objects of the construction of thought, and one can identify whose thoughts. They tend to suggest a certain objectivity, so it becomes also necessary to be able to identify the agenda of the authors. In any case, I’m not interested in objectivity, I am much more interested in bringing back subjectivity to architecture than anything else.

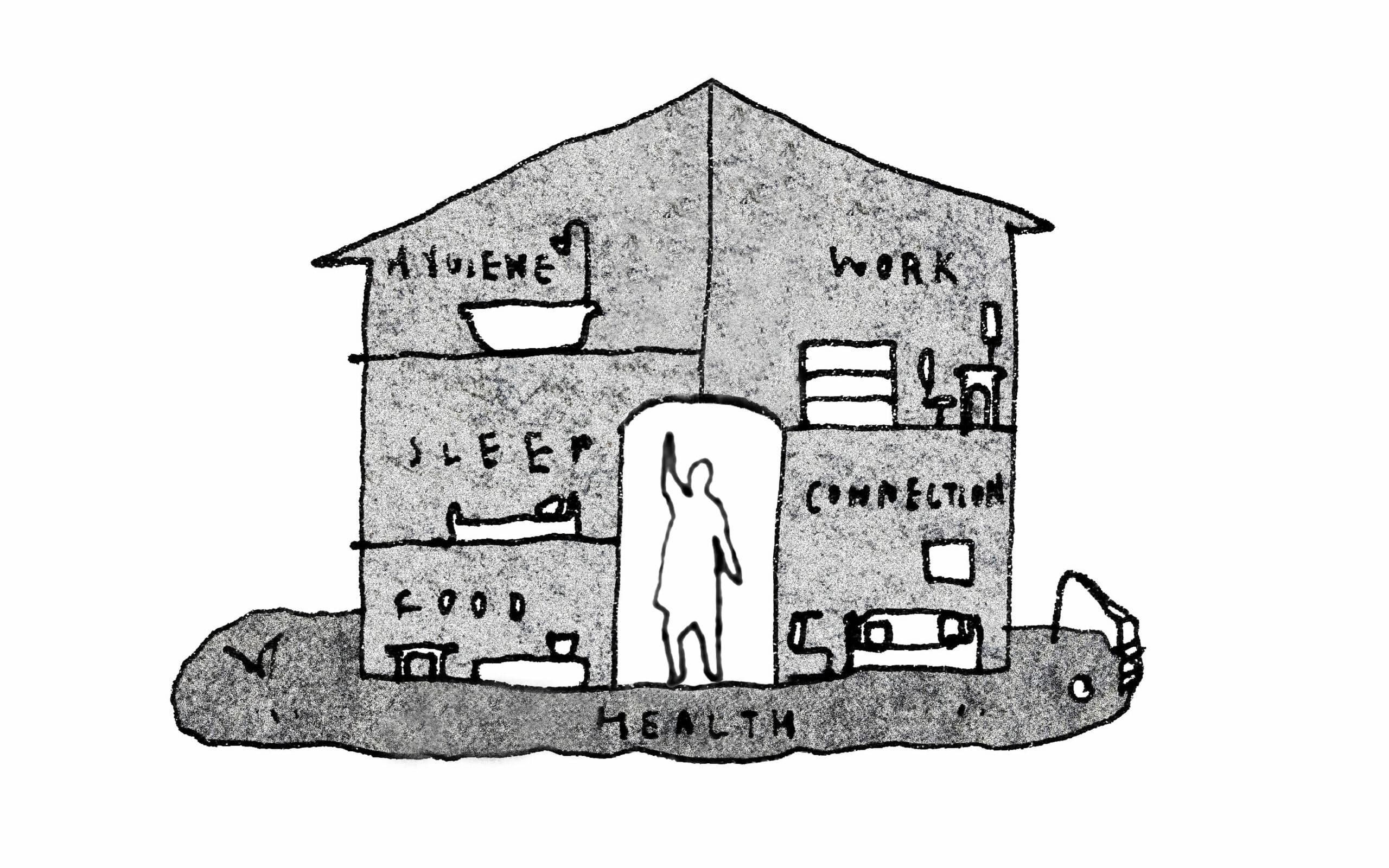

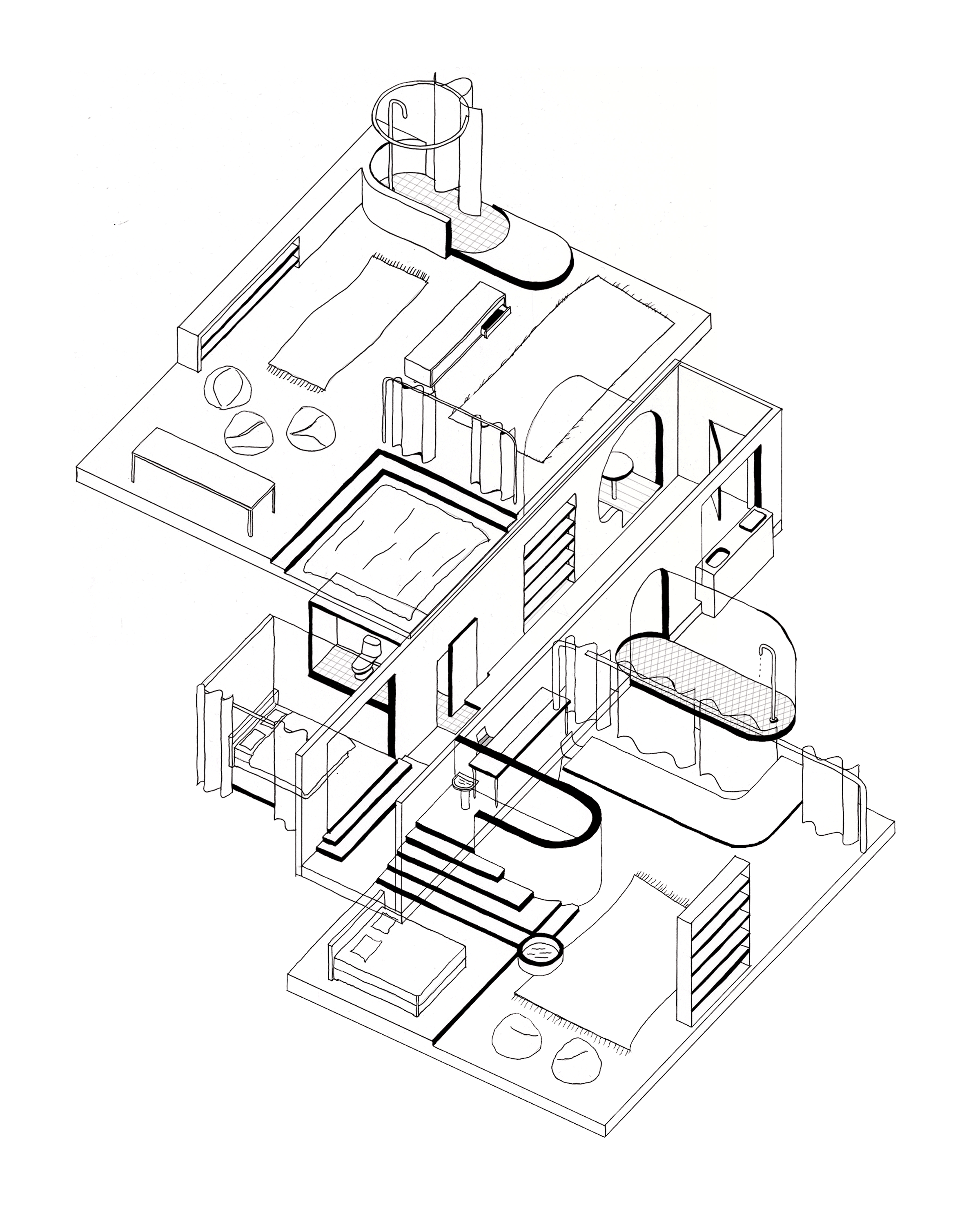

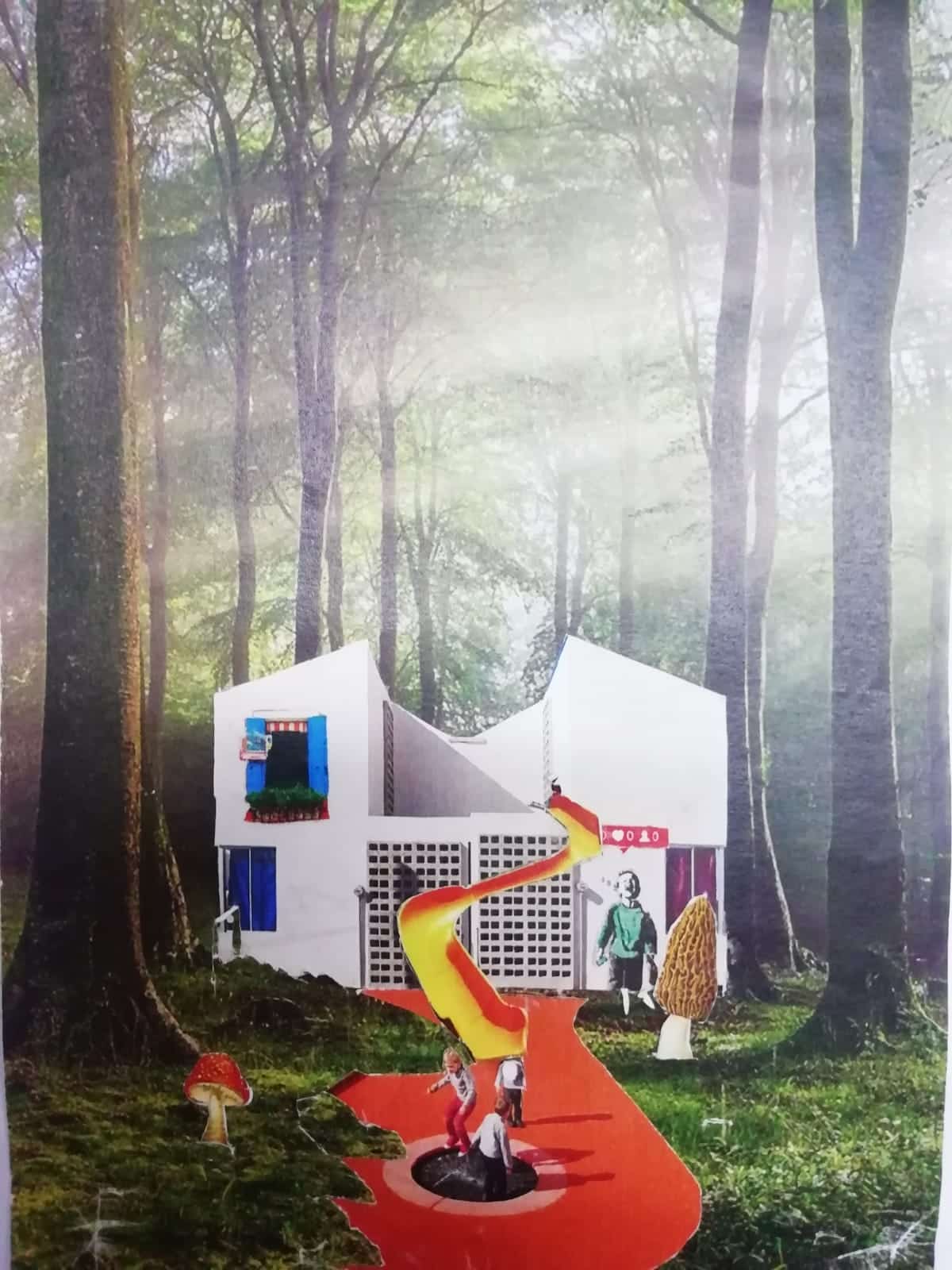

FG: You come from Mexico, a culture of a permanent tactical capacity for improvisation and response. So, when restrictions hit, your design studio moved online successfully with just a few tweaks. This semester you anticipated many incidents – travel was no longer an option – and so you proposed the ‘house’ as the topic. But then you escape from any banality about Covid-19, confinement, and invite the students to rethink ‘rooms’ as means to engage far wider cultural, political and social issues. I assisted with the midterm reviews and was struck by the intensity of the reflections, while they all played on very abstract and general approaches: universal rooms. Could you explain a little more about the pedagogy of your current studio? What have your students been tasked to do until now and what will come after?

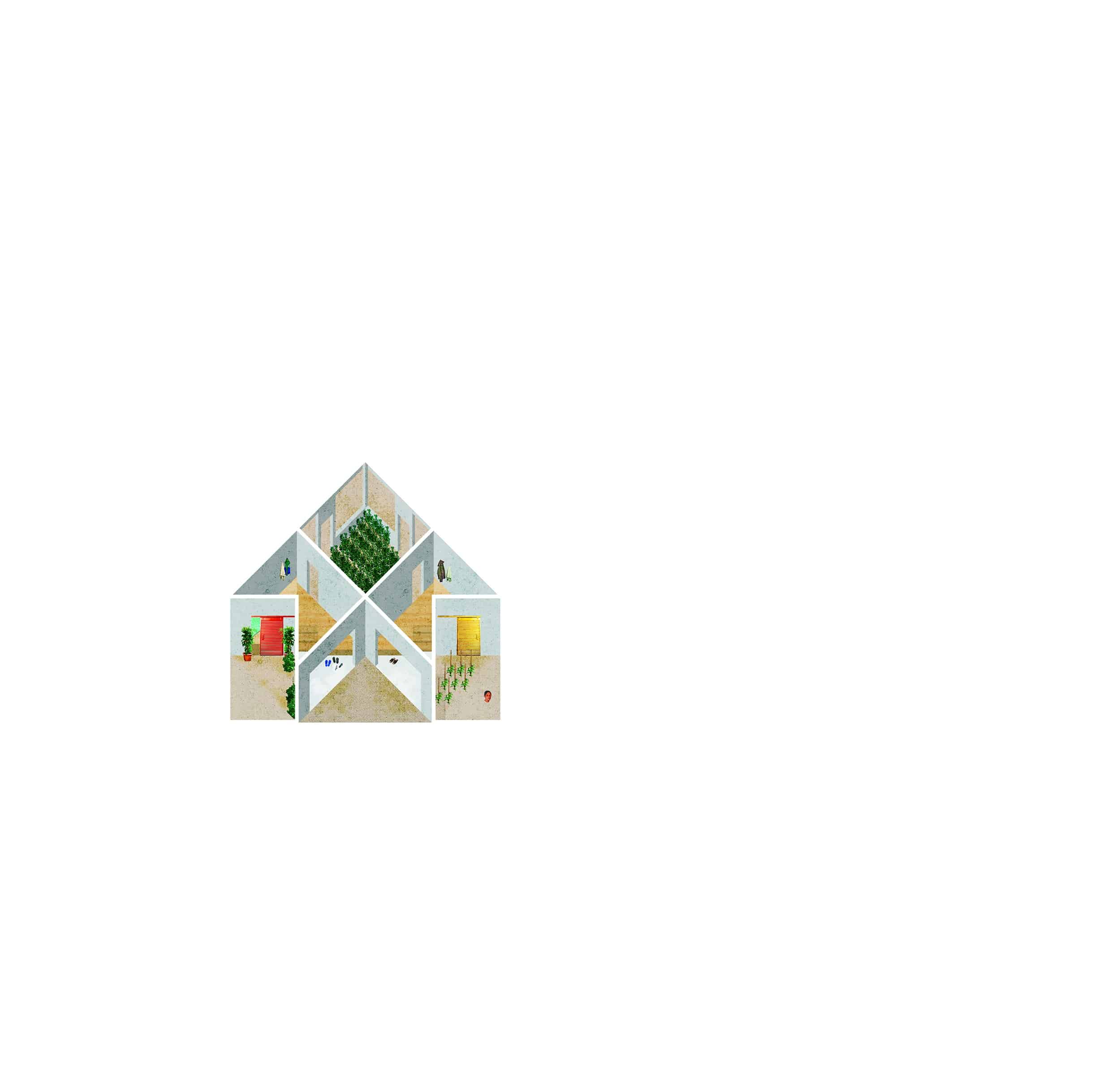

TB: The house is with no doubt the most contested architectural space of all and having being confined to one for over a year has made things even sharper. The intensity of the reflection, I think, comes from the fact that we are one of those small percentage of people being able to actually have a house and the opportunity to reflect on it. I think that the topic has become very urgent, right in the moment that our own entire existence has become the subject of exchange, meaning that we have become completely dependent on capital. For me, it is impossible to imagine teaching something else that would not question that basic structure in our life. The students, by looking at the house in fragments, are asked to question which structures are subjecting the individual that inhabits them and which ones are banning even our possibility of existence.

The students don’t have to design a domestic space, each of them through the analysis of a room have to develop a specific agenda on what the issues are that they want to contest in the domestic realm, as it is conformed to today. Each will hopefully end up with a design that addresses them, in any way they believe it will work.

FG: During your midterm review at Yale, I was struck how the students developed very compelling readings and early proposals for the future of the ‘domestic’ while reacting to references that were timeless. In one of the roundtables, Beatriz Colomina pointed out that the concept of ‘corridor’ is already quite old, and it is also an invention, not an archetypical absolute. And when I read ‘parlour’, in the list of rooms that were assigned I was very intrigued as it sounds as if it is from a Victorian novel. How did you choose the rooms? Some are obvious – bathroom or kitchen – others are less so, like the parlour or the laundry room.

TB: We took my interpretation of the spaces that compose the house from my understanding of ‘The American Dream House’, the ‘McMansion’ type. In reality, there are many more definitions, and spaces vary, so we took those that ‘normally’ have been used as descriptions of the ‘ideal’ house and used as symbols to determine status and condition. We also let the students choose; we gave them an initial brief and we asked them to get together and discuss the spaces to decide who would analyse them, they came up with the list. There was a discussion about whether we should leave out the corridor and analyse the ‘office’, but this function became controversial, so we decided to keep the corridor, and I was glad of that decision. The parlour is a very interesting room. Although having a parlour became a sign of social status in the Victorian era, this room existed first as the room where monks in monasteries would receive someone from the outer community without disturbing the inner community. This space became the kind of standard place for social interactions and then migrated from monasteries to the secular world. I believe there is a potentially very interesting idea in having a space specifically where you can share yet be intimate within your own ‘space’.

Associate Critics

2018, 2020: Andrei Harwell

2021: Karolina Czeczek

Tatiana Bilbao Estudio Partners

Catia Bilbao

Juan Pablo Benlliure

Alba Cortes

Mariano Castillo