Pembroke’s Archives

Alison Turnbull was appointed lead artist for the Mill Lane development at Pembroke College, University of Cambridge in 2020. Drawing on objects from the College Archive and working in close collaboration with architects Haworth Tompkins and landscape architects Tom Stuart-Smith Studio, she has created permanent works for the new interior and exterior spaces. There are two wall paintings in the Foyer and a rill and paving design for Chiu Court.

The following texts were first published in the artist’s book that accompanied the project (2023).

The Foyer

The new foyer building is part of a complex sequence of spaces that together form a layered threshold between Trumpington Street and the new garden spaces of the expanded College. The foyer itself sits within an informal enclosure of several historic buildings of diverse scale, age and character. Its form is defined by an expressed timber frame that describes a subtle arc in plan between the shifting geometries of the existing masonry structures. The ‘found’ surfaces of brick and stone bear the traces of past interventions, revealing the layered history of the site’s evolution and inhabitation. Our design approach seeks to weave these historic narratives into the future spaces, creating an architectural palimpsest that reflects the centuries-long development of the city and College.

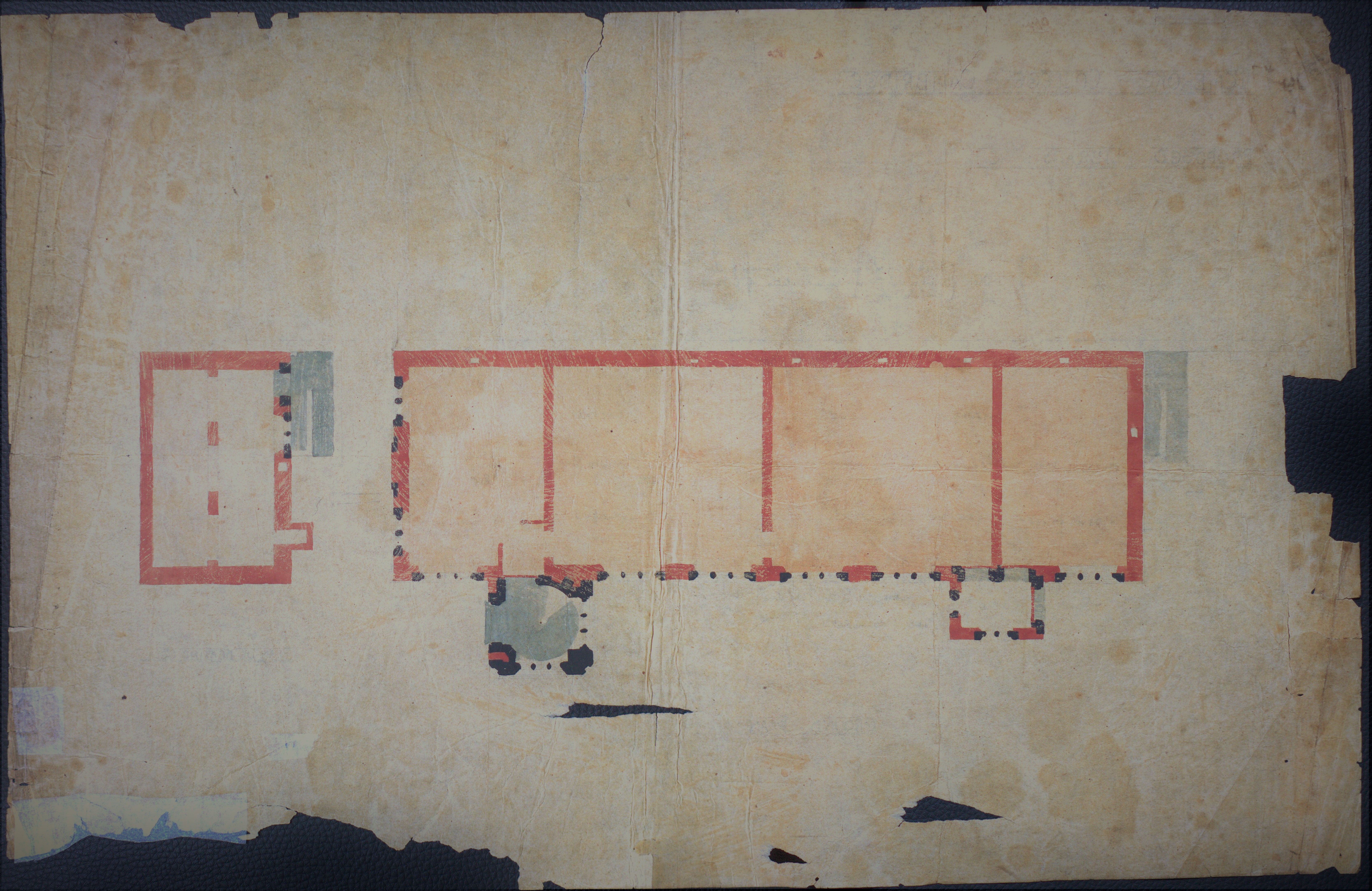

There are intriguing parallels here with the way in which Alison has drawn on material from the College Archives. The historic architectural drawings referenced in her work are both documentary evidence of the evolution of the College and physical objects that exhibit traces of the individuals and processes through which they were made: hand-written notes, ink stains and the markings of age that now form part of the drawings’ composition.

Our early conversations with Alison roamed freely around these potential points of convergence in our work and hers; and in the dualities embedded in our collaborative approach: digital and analogue; precision and chance; permanence and transience.

Beatie Blakemore, Architect

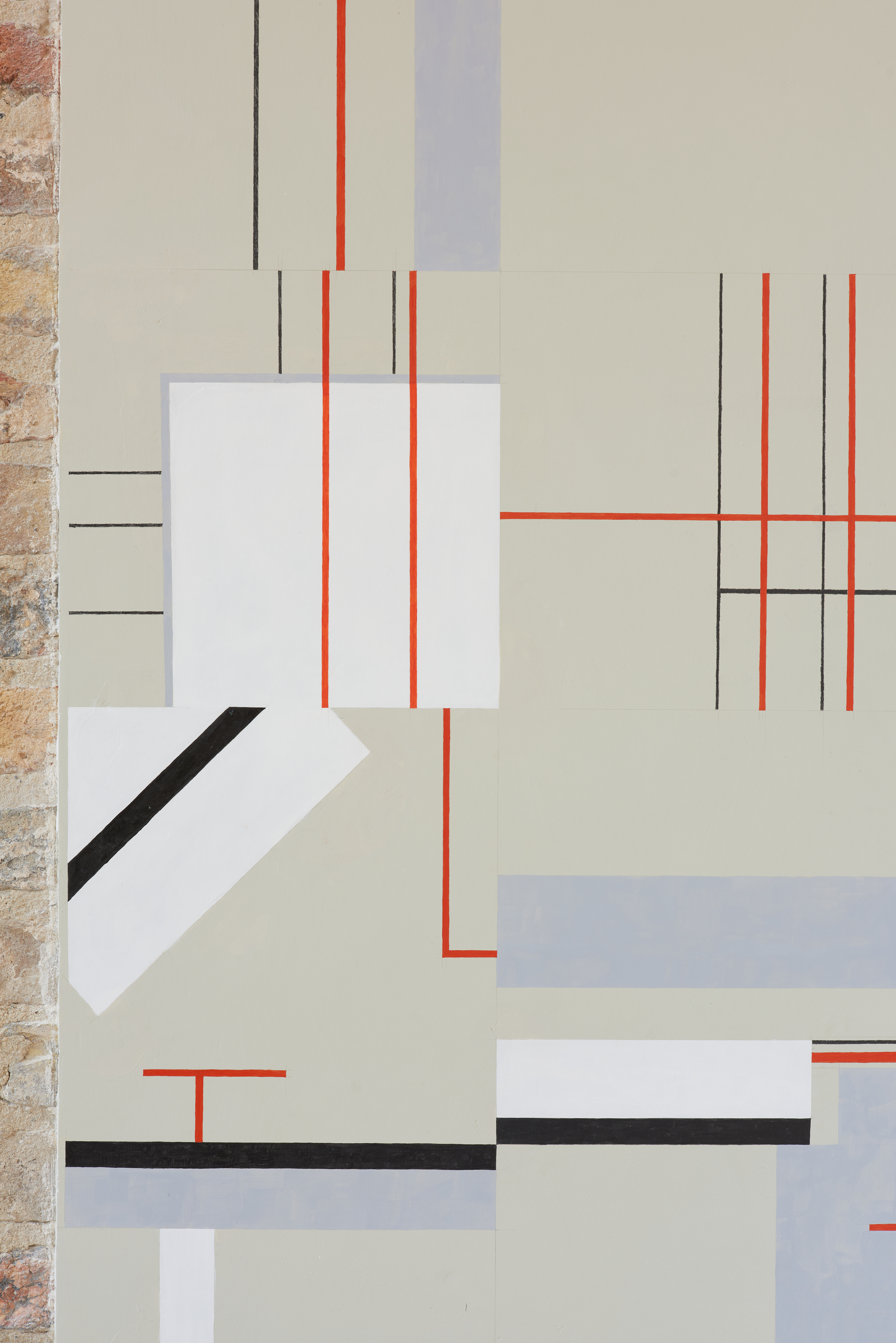

Navigating my way around plans and models and conversations with the architects, I decide to make two paintings for either end of the long, airy space that looks onto the courtyard garden. The walls are bare brick—one a highly textured existing façade, the other newly made from old bricks—a far cry from the white walls of my studio or a gallery. The best option is to make a smooth plaster surface for the paintings directly onto the brick and work in situ. Found walls for paintings made from found drawings.

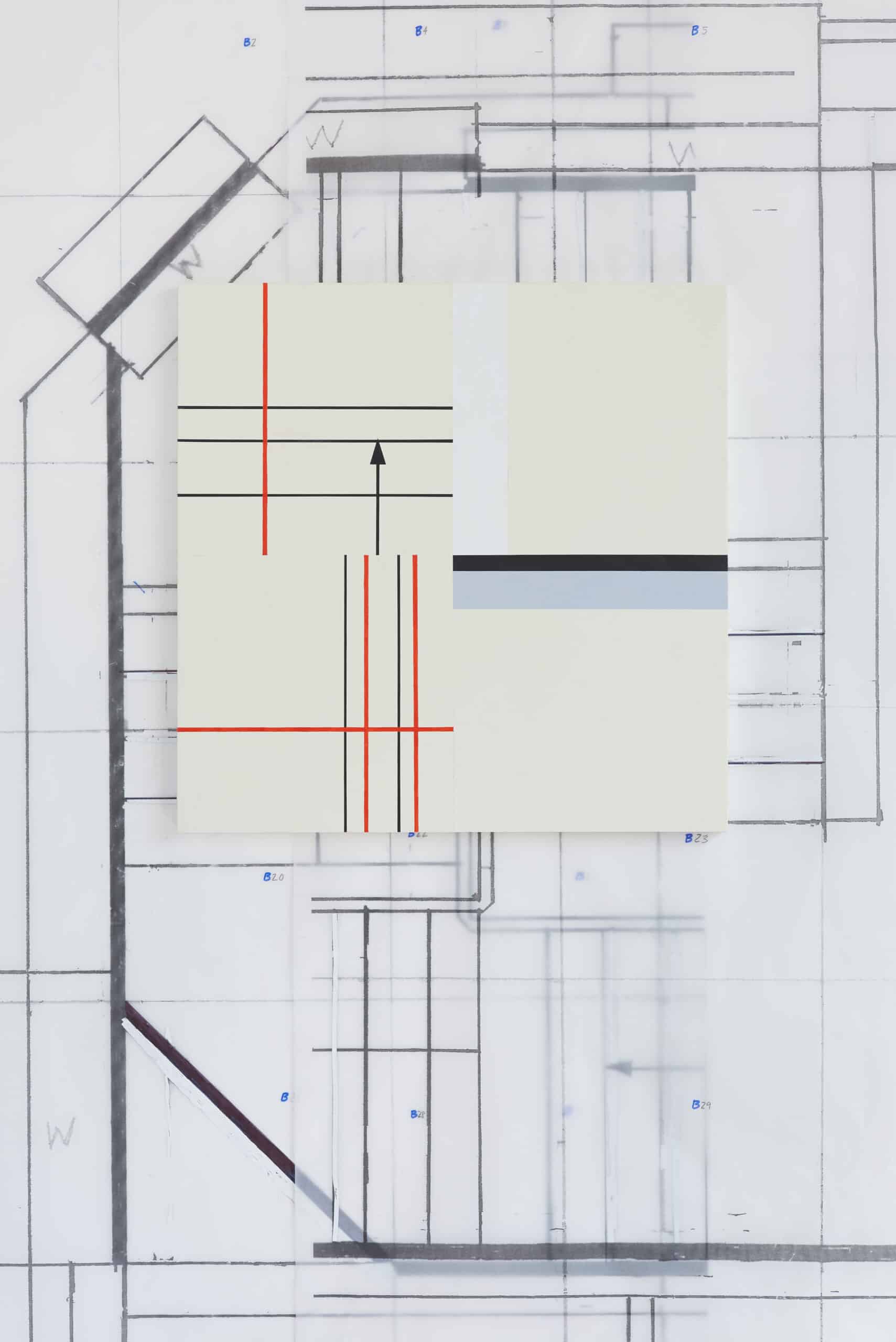

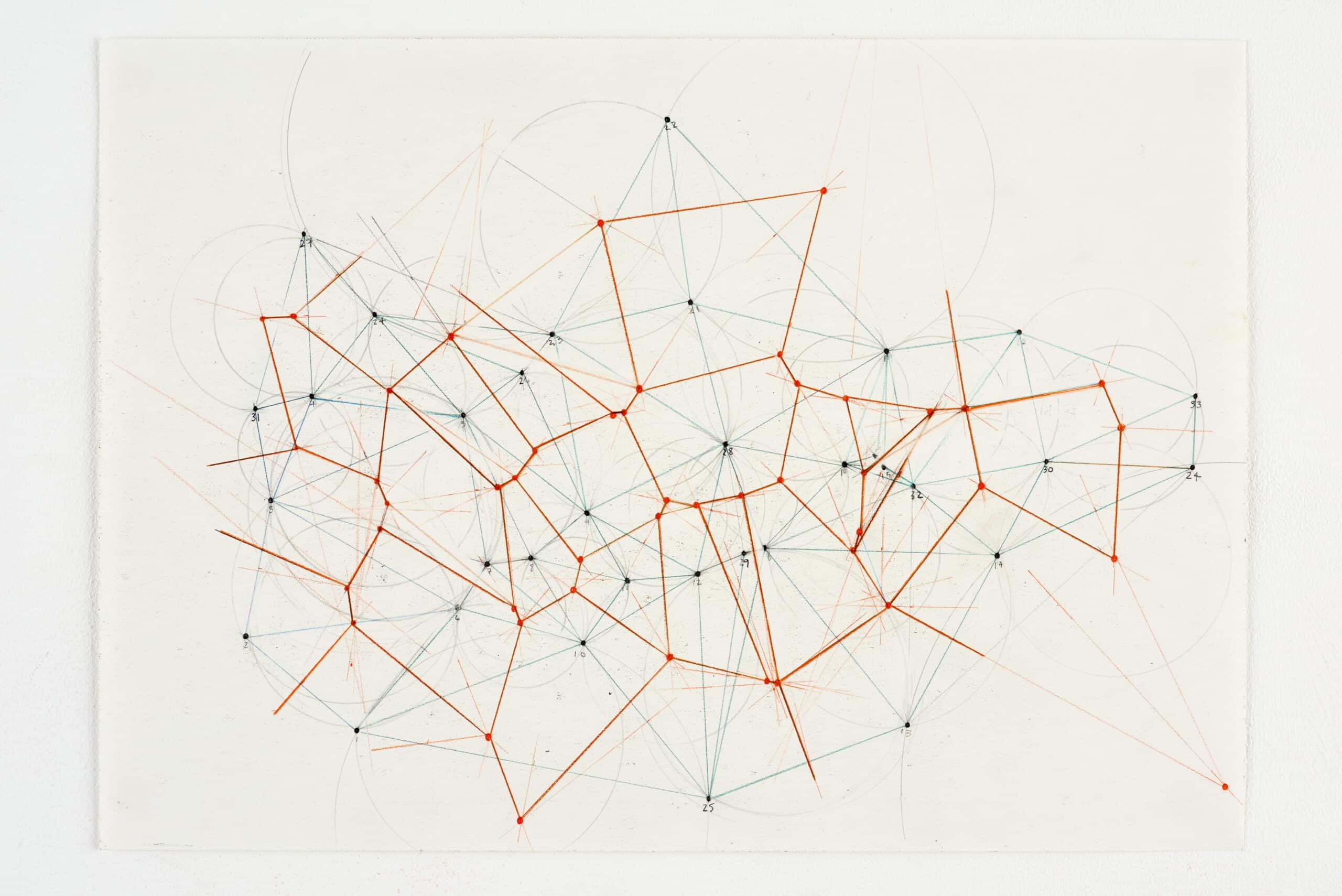

I look at the architects’ digital drawings on screen and at 19th and early 20th-century drawings in the archive, all made for expansions and renovations at the College. Staircases, liminal spaces of chance encounters, are everywhere at Pembroke and feature in all the drawings I’m working with. But whereas Haworth Tompkins’ drawings are made with sophisticated computer-aided design tools, the earlier drawings are handmade with watercolour on tracing paper, in pale blues, pinks and ochres, interlaced with black lines. Both approaches inflect my work.

Rather than floating an image of the found plan onto the picture plane, I make tracings and drawings from the architectural plans, which are enlarged, cut up and rearranged by chance. Along with colour, forever unpredictable, there is an aleatory compositional element structuring these paintings. There are no preliminary sketches. I’m focusing on the found material and the process of making the paintings; I don’t know what they will look like.

Courtyard Garden

On one side of courtyard, away from the main route, which most people will use, we have made a more settled and contemplative space, composed of two stone benches and a Catalpa tree. Here we have had the happy opportunity to collaborate with Alison Turnbull to create an ensemble of art and landscape that we hope will encourage people to linger, think and question. We worked closely with Alison to convert her drawings and mock-ups into digital information that could be used to build the work to very tight tolerances.

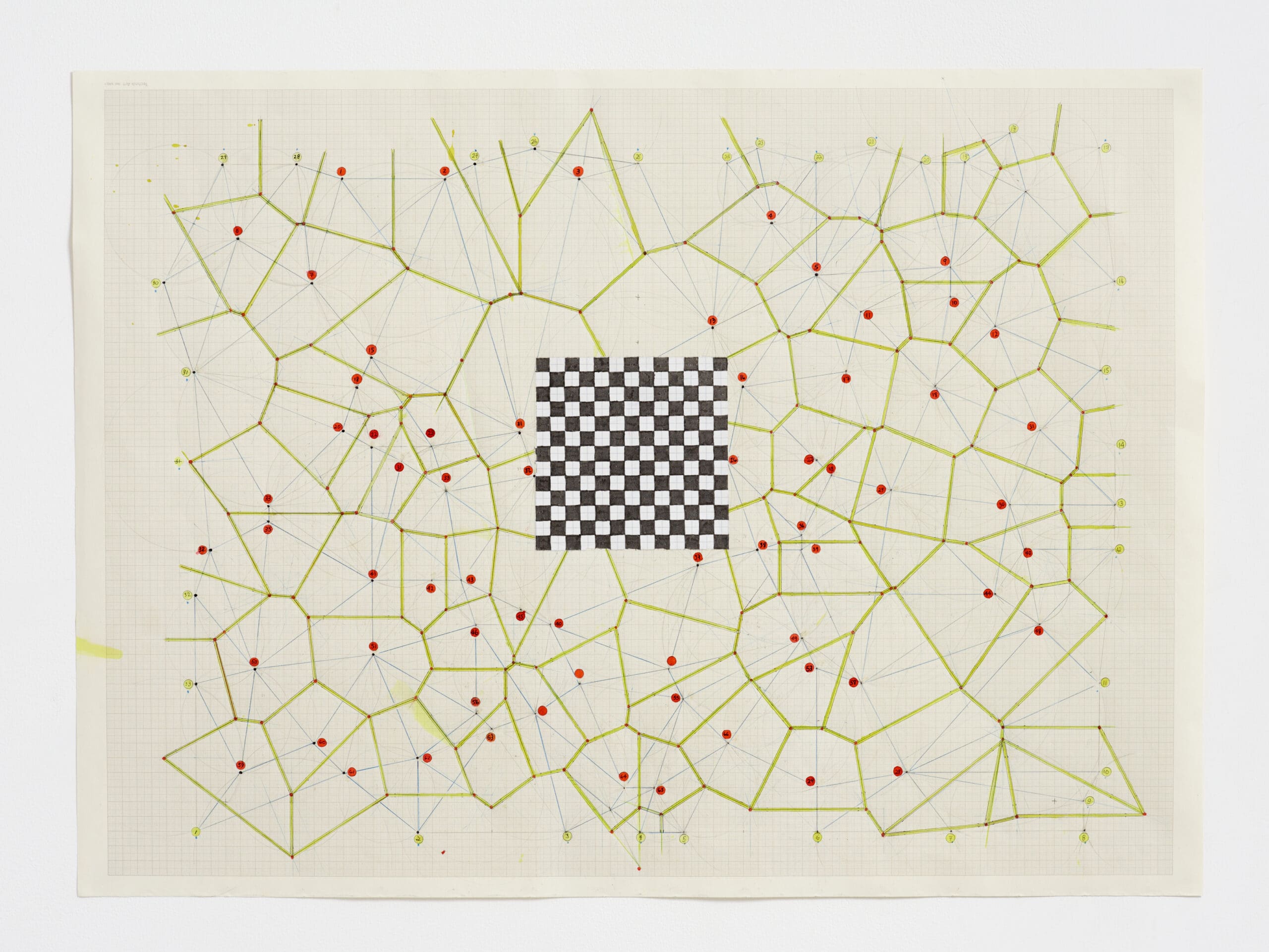

The outer part of the work is formed by a Voronoi pattern of cut York stone, like an exact mathematical version of a giraffe skin, derived from connecting lines that are equidistant between points in space. Within the frame of the stone benches is a tiled area suggesting another story, another space within the space. A bowl sits at the side of one of the benches; water emerges, spills down onto another bowl in the paving, and trickles across the centre of the mosaic in a very narrow channel. Standing here it is possible to see the two related paintings in the interior of the Foyer, suggesting a conversation between them and between inside and outside. So the courtyard becomes a space of interactions, conversations and questions.

The planting around the courtyard continues a college tradition of using the rare and exotic. In time this will be both abundant and luxuriant.

Kurosh Davis, Landscape Architect

As a painter, my preoccupation is with vertical surfaces that you can see from a long way away, if the space is big enough, and extremely close to—if you’re curious enough. I’ve always wanted to design a paving, a horizontal surface that is experienced bodily as much as visually.

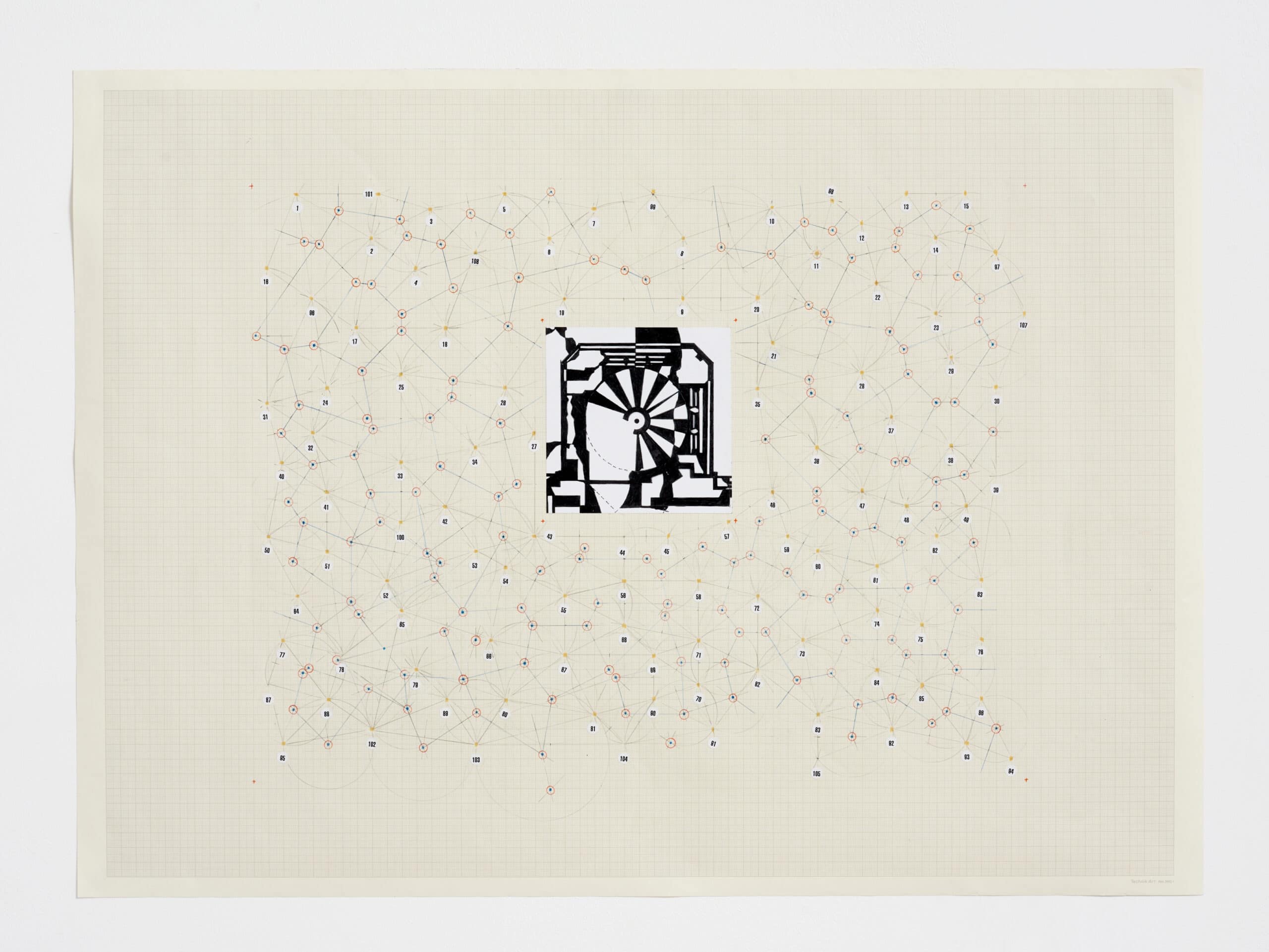

These dualities, not just vertical and horizontal, but inside and outside, process and image, colour and monochrome, come together collaboratively in our ‘ensemble of art and landscape’. Kurosh transformed my drawings into something workable and together we considered materials. We were helped by Gábor Csányi, Professor of Molecular Modelling and Pembroke Fellow. Working from my tessellation, and a list of coordinates, he subtly corrected our Voronoi pattern, which ensured scientific accuracy while still allowing for the possibility that the physical realities of stone, flowing water and a large Catalpa tree might put pressure on abstract mathematical perfection.

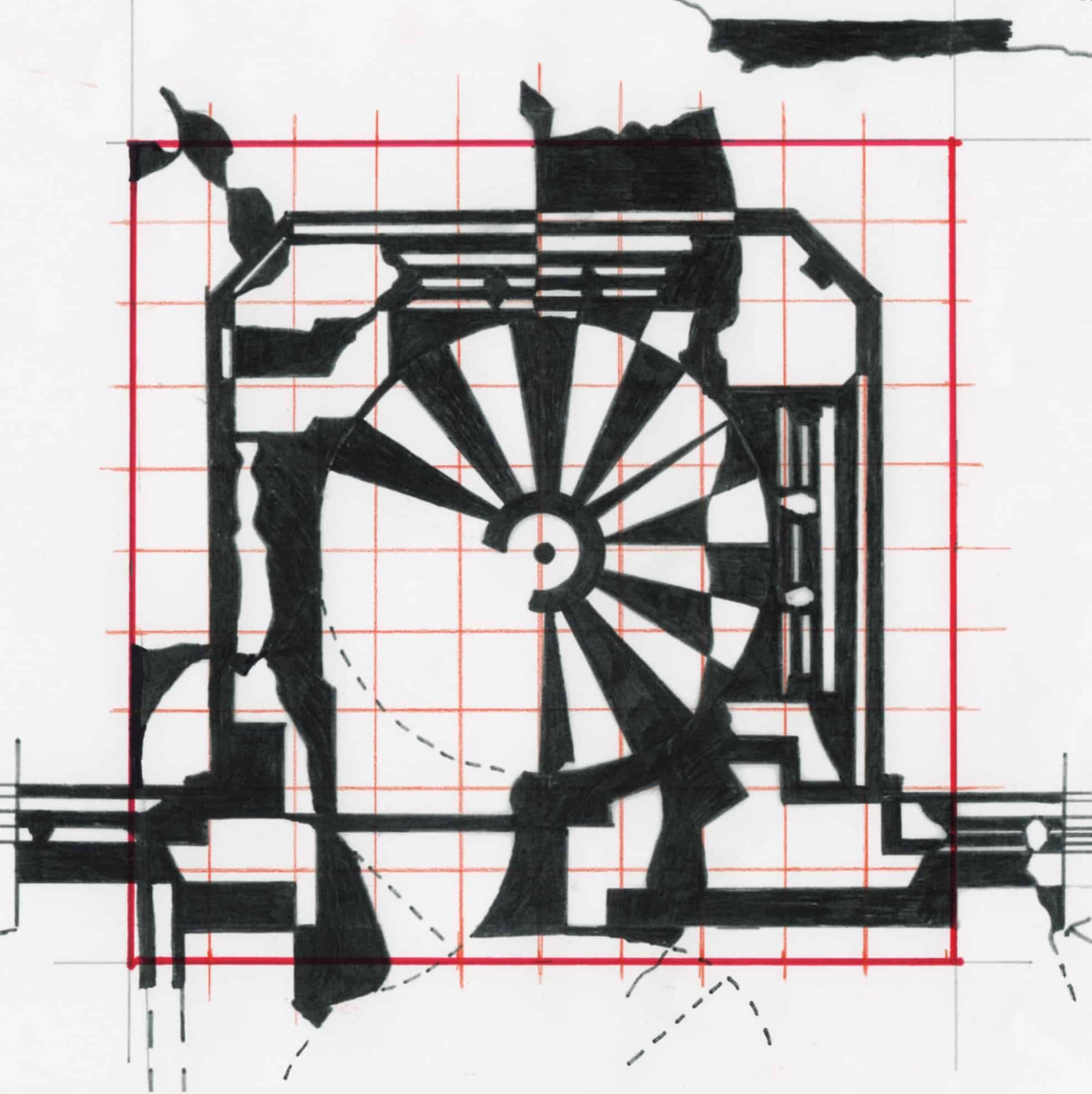

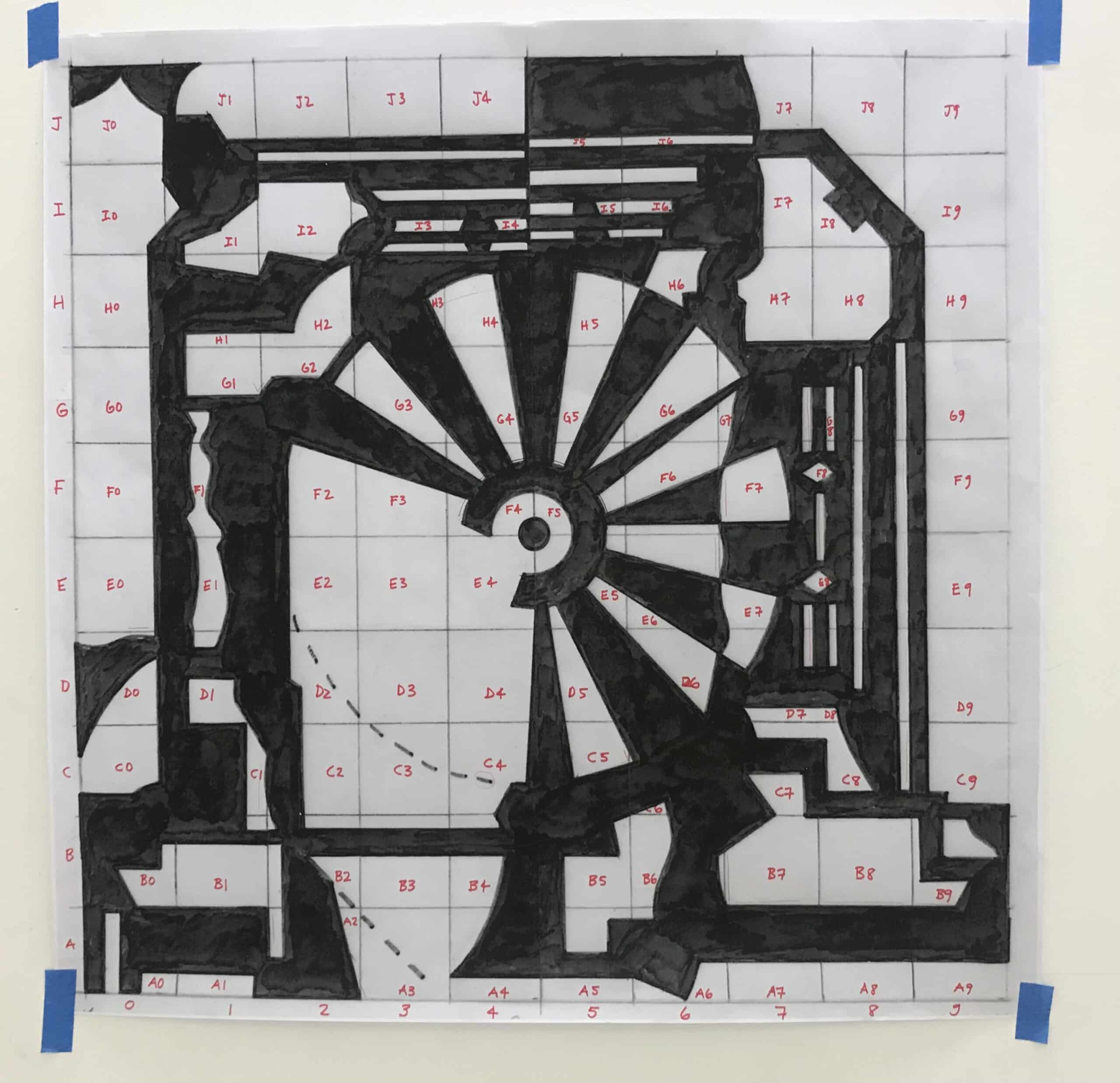

The Voronoi process gave me a way of disrupting the conventional paving grid but I was also searching for an image to generate the central black and white mosaic.

In the archive I found a 19th-century drawing by Alfred Waterhouse, architect of the College Library. Uneven marks made by folds, stains and tears crisscrossed its carefully drawn lines. I homed in on the library’s spiral staircase and decided to treat everything—marks made by the architect and those made by time—in the same way, creating a template for the porcelain mosaic that sits at the heart of the courtyard.

Alison Turnbull transforms readymade information (plans, diagrams, blueprints, charts) into abstract paintings and works on paper. Turnbull’s interest in architecture has been the starting point for much of her work and has led to a number of architectural commissions and projects in public spaces.