Postmodern Australia: Robert Pearce’s Drawings for Edmond and Corrigan

Writing in Cities of Hope (1993), the historian Conrad Hamann relates that, on mentioning to Robert Venturi the name of the Australian postmodernist architect Peter Corrigan, the first words from Venturi’s mouth were ‘Oh God! Corrigan!’. Yet it must be made clear that to Corrigan, and to his wife and fellow architect, Maggie Edmond, the Venturis were by no means the enemy – Antipodean postmodernist architecture resembles its American cousin, by appropriating the vernacular into its idiom, and by apotheosising the everyday and the unschooled. Still, like all global movements, it cannot avoid the shibboleth of a local vernacular. For the Melbourne-based practice of Edmond and Corrigan, this is the phrase ‘larrikinism’, or well-intentioned mischief. Such disruptive familiarity, alongside imagery derived from suburbia and the theatre, defines the practice’s formal and representational bodies of work.

The fashion illustrator Robert Pearce – who had, as per Corrigan, ‘a highly personal and evocative flash-trash graphic style’ – made, while in Edmond and Corrigan’s employ, drawings that are powerful signifiers of the practice’s irreverent and surrealistic modes. Pearce’s drawings, disseminated through books, journals, competitions, and exhibitions, constitute the practice’s critique of the established rules of Australian architecture, and its dialogue with other architects. A rendering of the Barber House (1979) in Melbourne typifies Pearce’s pictorial output for the practice. In a manner that recalls Edmond and Corrigan’s portfolio of designs for the theatre, the built forms in the Barber House drawing appear like a stage backdrop, and the human figures, in turn, are presented similar to costumed performers and are placed around rather than within the architecture. The stippling technique of the image, richly applied and without the mediating relief of an ink wash, creates a tenor of excess and intensity. The detailed figures – complete with cartoon speech balloons and the patterns and textures of their clothing – run counter to the widespread conventions of architectural drawing, which call for the entourage to be plain and inconspicuous. Pearce’s drawings, for the Barber House and other designs by Edmond and Corrigan, encapsulate the individuality, jocosity, and reflection of placeness that are central to postmodernism and to the practice’s thinking.

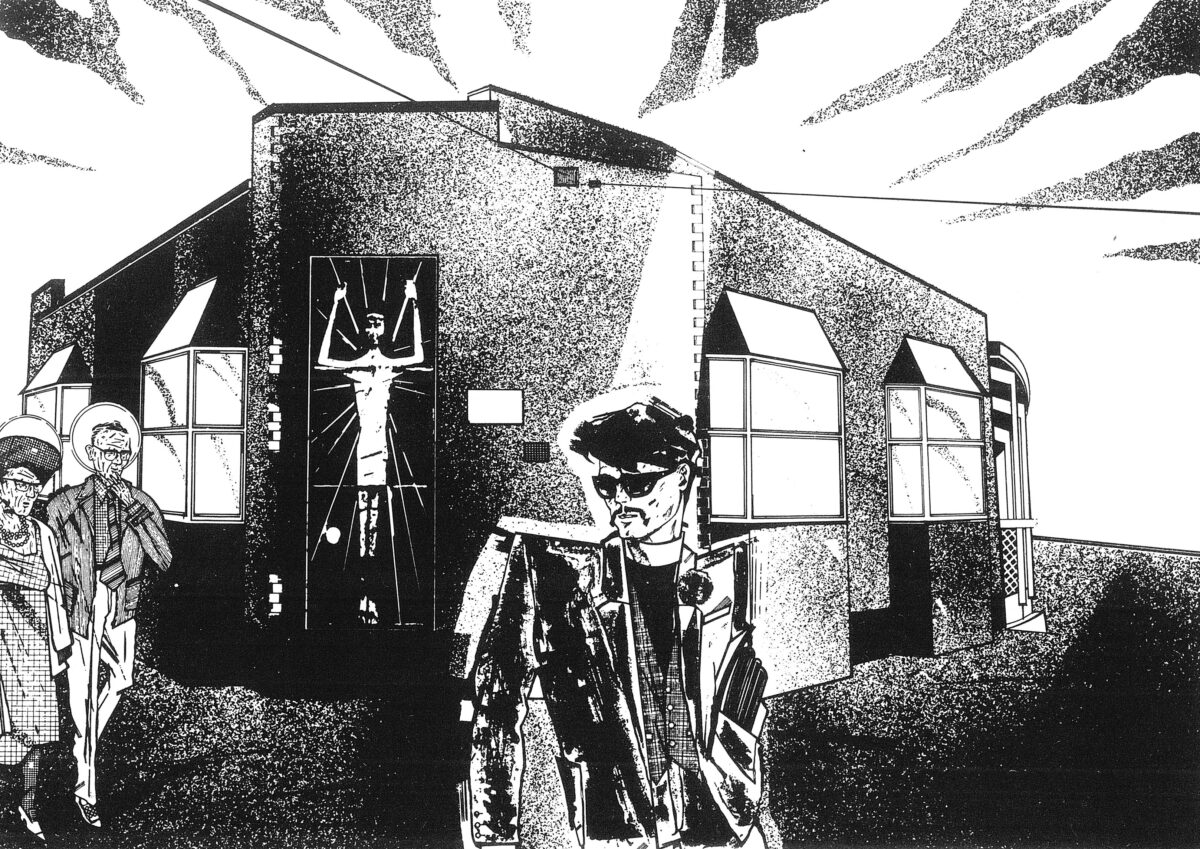

In Invocation (c.1980) for the Church of the Resurrection in Keysborough, Melbourne – a seminal example of late-twentieth-century and post-Vatican II ecclesiastical design in Australia – Pearce rendered the liturgical east end of the church, with four suburban bay windows and an iconographic stained glass of a risen Christ. The lines in the drawing are laid down strongly and without ambiguity, in a way that disallows any fuzzy edges. The forms of the architecture and the human figures are expressed with great clarity. However, an identical stippling, for both the ground and the walls, suggests that they are made of the same material. The horizon, to the right of the scene, is unrealistic, being too low and too exact in its delineation of the ground and the sky, without any landscape to visually soften the transition. A pair of cables, projecting from the centre wall, would in architectural drawings usually be considered distracting and unsightly. Here, they are deliberately retained, clashing with the drawing’s invisible perspectival lines, and so upsetting, albeit slightly, the overall harmony of the view.

In the Keysborough Church drawing, the rays that emanate from behind the building are less effective as a reminder of the sun in a literal sense, than they are as a reminder of the building’s divinity. The parish priest, modern and urbane, balances fashionable eyeglasses with an armful of books, and receives heavenly favour in the form of a shaft of light, while two elderly parishioners approach him cautiously and in hushed reverence, with their middle-class, Sunday best attire offset by aureoles – a sainted figure with two angelic attendants. While the religious symbolism of the drawing may be tongue-in-cheek, it does not descend into mockery, and there is no condescension to the parish church and its users.

Edmond and Corrigan’s entry for the Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame and Outback Heritage Centre competition in Longreach, Queensland, is located not in the suburbs, but in an equally iconic Australian setting – the bush. Corrigan described that the design intent was for the ‘submerged structures’ to carry ‘reassuring touches of an identifiable suburbia’, with their imagery one of a ‘desperate gesture’ and a ‘forlorn hope’. Such aspirations take on even more poignant meaning, in the knowledge that the design was and will remain unrealised, and that its drawings are, along with its verbal and written descriptions, the only means to connect with its architecture.

The most significant entourage, in the Stockman’s Hall of Fame and Outback Heritage Centre (c.1980) drawing, consists of aeroplanes, windmills, and a trio of stockmen, all of which, in their strangeness, collide with rather than complement the architecture. The stockmen and the windmills are imbued with the mythos of the bush. The stockmen are rendered with full awareness of their sanctity in the Australian imagination, evoking robust nationalism on the one hand, and glossy commercialism on the other. But the world that is suggested by the drawing is – in spite of the bristling masculinity of the stockmen, and the kinetic energy of the windmills and of the aeroplanes and their pursuant jet streams – melancholic and wistful. It brings to mind a museum, or even a mausoleum, that queries the relevance of a pioneer outback in an urbanised, late-twentieth-century Australia, and then attempts to comprehend the disconnection. Perhaps this aspect of the national identity is moribund, to be no longer legitimately experienced in the present day, and to be only experienced vicariously through the architecture, artwork, and poetry that memorialise it.

The Australian practice Edmond and Corrigan challenges modernist conformity with postmodernist diversity, in which the everyday is embraced and the common is given iconicity. Pearce’s drawings are important enablers of the practice’s stance because they not only communicate but embody the larrikinism, suburbia, and theatricality of the practice’s approach. They underscore the capacity of architectural drawings to function as critically and as persuasively as the architecture itself.

Yvette Putra is a Melbourne-based academic researching and teaching architectural design, history, and theory.

This text was entered into the General Archive category for the 2021 Drawing Matter Writing Prize.